Practice Essentials

Tracheomalacia is an abnormal collapse of the tracheal walls. [1] It may occur in an isolated lesion or can be found in combination with other lesions that cause compression or damage of the airway. Tracheomalacia is usually benign, with symptoms due to airway obstruction. As such, this condition is often mistaken for chronic asthma or prolonged bronchiolitis.

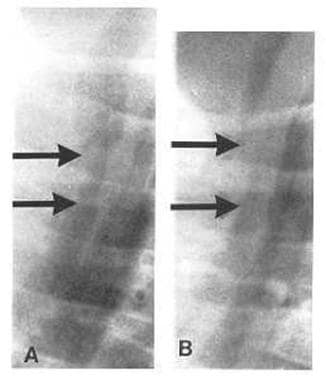

This shows the trachea during inspiration and expiration. Tracheal collapse of more than 50% during expiration is diagnostic of tracheomalacia.

This shows the trachea during inspiration and expiration. Tracheal collapse of more than 50% during expiration is diagnostic of tracheomalacia.

Signs and symptoms

The history of a patient with tracheomalacia typically includes a wheeze that usually begins when the individual is aged 4-8 weeks. The wheeze generally increases with activity and colds and decreases during quiet periods.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The definitive method of diagnosis is bronchoscopy.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

After the diagnosis of tracheomalacia is made, the most effective and safest treatment is allowing time to pass ("tincture of time").

Surgery may be an option when an infant has one or all of the following:

-

Difficulty gaining weight and developing

-

Recurrent pneumonia or apnea

-

Enough airway obstruction to require long-term airway support

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Pathophysiology

Tracheomalacia may occur as a primary lesion, in which case the cartilage of the trachea develops abnormally. This results in tracheal walls that are soft and collapse during respiration. The collapse causes airflow obstruction and wheezing, stridor, or both. If the lesion is extrathoracic, the collapse and airway sounds occur primarily during inspiration. If the lesion is intrathoracic, the collapse and airway sounds occur primarily during exhalation. Because most of the trachea is intrathoracic, exhalatory collapse accounts for most cases of tracheomalacia.

Tracheomalacia may also be found in conjunction with lesions that compress the airway, such as mediastinal masses, vascular slings, and vascular rings. It also occurs with increased frequency in children with chronic inflammation of the proximal airways. Less common in asthma, this etiology of tracheomalacia is more often seen in children with chronic lung disease of infancy, gastroesophageal reflux, or other forms of chronic aspiration.

Primary tracheomalacia is sometimes referred to as type 1, tracheomalacia associated with extrinsic compression is sometimes referred to as type 2, and tracheomalacia associated with intra-airway irritation/inflammation is sometimes referred to as type 3.

Tracheomalacia is frequently found after repair of a tracheoesophageal fistula and may cause significant symptoms for several years after the repair.

Etiology

As far as tracheomalacia is understood, most cases are isolated and idiopathic. A recent study proposed a possible neurologic etiology for tracheomalacia. This group was caring for a child with increased intracranial pressure. When the pressure was elevated, the child developed tracheomalacia. When the pressure was relieved, the tracheomalacia remitted. This scenario recurred, although the etiology for increased intracranial pressure causing tracheomalacia is unknow. [2]

Transient defects in tracheal cartilage development are assumed to be the cause of this condition. This is sometimes referred to as type 1 tracheomalacia.

Autopsy data are lacking, and no animal model is noted.

Some children with tracheomalacia have the lesion because of vascular anomalies or other causes of compression of the airway. This is referred to as type 2 tracheomalacia.

Tracheomalacia is a common finding after repair of a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Tracheomalacia may occur with and complicate other disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, other forms of recurrent aspiration, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (chronic lung disease of infancy).

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The frequency of tracheomalacia is unclear. The condition appears to primarily derive from a developmental defect in the cartilage of the tracheal wall. Therefore, the lesion usually occurs in infants and young children. It is frequently found in children who have undergone repair of a tracheoesophageal fistula, chronic lung disease of infancy, vascular compression of the airway, or mediastinal masses of sufficient firmness to compress the airway. Children with gastroesophageal reflux, or aspiration from above, have an increased incidence of tracheomalacia. The problem in this last situation is trying to decide which condition is the cause and which is the effect.

International statistics

Data from the Sophia Children's Hospital in Rotterdam (southwest Netherlands), the only facility in that country performing bronchoscopy in children, suggest an incidence rate of 1 case per 2100 newborns. [3]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No racial predilections are known.

No gender predilections are known.

Because most cases of tracheomalacia appear to be related to a developmental defect in the cartilage of the tracheal wall, the lesion typically occurs in infants and young children. In most children, the tracheal cartilage normalizes, the airway enlarges, and symptoms resolve by 3 years of age (in many before age 1 y).

Because tracheoesophageal fistula is usually repaired early in life, the associated tracheomalacia also appears in early infancy, usually shortly after surgery.

If the tracheomalacia is a result of compression, the patient's age at presentation depends on the cause of compression. Vascular rings, present from birth, cause tracheomalacia early in life. Other causes of compression, especially tumors, occur later in life.

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent. Most patients outgrow this condition by the time they are aged 3 years; many infants outgrow tracheomalacia before they are aged 1 year.

If gastroesophageal reflux is present, attention to this speeds healing.

Tracheomalacia after tracheoesophageal fistula repair may take longer to heal than primary tracheomalacia. Tracheomalacia after a compressing lesion lasts longer, depending on the length of time of the compression.

A study that included 55 pediatrics patients diagnosed with tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia reported that severe malacic lesions indicated surgical intervention and worse clinical outcomes for patients with tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia who had acute life-threatening events and extubation failure. [4]

Morbidity/mortality

Morbidity and mortality are extremely rare. On occasion, tracheomalacia causes enough obstruction to necessitate intervention. This obstruction generally takes the form of episodic severe airway obstruction causing cyanosis. When infants with chronic lung disease of infancy become irritated, they may have what has been called a "BPD fit." This episode usually involves a cry, with either a breath hold or with a sufficient increase in intrathoracic pressure to partially occlude the airway. If the child has tracheomalacia, the frequency and severity of these episodes is often increased.

Complications

Severe obstruction requires acute intervention with mechanical ventilation or positive pressure.

Chronic obstruction necessitates surgical intervention (eg, tracheostomy, stent placement, aortopexy).

Aortopexy and stent placement have been compared over a 10-year followup. [5] Both are equally effective in improving symptoms and allowing for normal growth and development. Aortopexy is associated with more perioperative complications, whereas stents are associated with long-term complications and the need for removal.

A case-control study by Thomas et al demonstrated that children with tracheomalacia are at increased risk of developing bronchiectasis (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 13.2). For those with tracheomalacia that meets the definition established by the European Respiratory Society (greater than 50% expiratory reduction in the cross-sectional luminal area), the risk is even higher (adjusted OR, 24.4). [6]

-

Slide tracheoplasty and left PA sling repair. Procedure performed by Giles Peek MD, FRCS, CTh, FFICM, The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY.

-

This shows the trachea during inspiration and expiration. Tracheal collapse of more than 50% during expiration is diagnostic of tracheomalacia.