Practice Essentials

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) have abnormalities in the metabolism of androgens and estrogen and in the control of androgen production. PCOS can result from abnormal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. [1] A woman is diagnosed with polycystic ovaries (as opposed to PCOS) if she has 20 or more follicles in at least 1 ovary [2] (see the image below).

Signs and symptoms

The major features of PCOS include menstrual dysfunction, anovulation, and signs of hyperandrogenism. [3] Other signs and symptoms of PCOS may include the following:

-

Hirsutism

-

Infertility

-

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

-

Diabetes

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

On examination, findings in women with PCOS may include the following:

-

Virilizing signs

-

Acanthosis nigricans

-

Hypertension

-

Enlarged ovaries: May or may not be present; evaluate for an ovarian mass

Testing

Exclude all other disorders that can result in menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism, including adrenal or ovarian tumors, thyroid dysfunction, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinemia, acromegaly, and Cushing syndrome. [4, 5, 6]

Baseline screening laboratory studies for women suspected of having PCOS may include the following:

-

Thyroid function tests [6] (eg, TSH, free thyroxine)

-

Serum prolactin level [6]

-

Total and free testosterone levels

-

Free androgen index [6]

-

Serum hCG level

-

Cosyntropin stimulation test

-

Serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHPG) level

-

Urinary free cortisol (UFC) and creatinine levels

-

Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test

-

Serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)–1 level

Other tests used in the evaluation of PCOS include the following:

-

Androstenedione level

-

FSH and LH levels

-

GnRH stimulation testing

-

Glucose level

-

Insulin level

-

Lipid panel

Imaging tests

The following imaging studies may be used in the evaluation of PCOS:

-

Ovarian ultrasonography, preferably using transvaginal approach

-

Pelvic CT scan or MRI to visualize the adrenals and ovaries

Procedures

An ovarian biopsy may be performed for histologic confirmation of PCOS; however, ultrasonographic diagnosis of PCOS has generally superseded histopathologic diagnosis. An endometrial biopsy may be obtained to evaluate for endometrial disease, such as malignancy.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Lifestyle modifications are considered first-line treatment for women with PCOS. Such changes include the following [4, 5] :

-

Diet

-

Exercise

-

Weight loss

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacologic treatments are reserved for so-called metabolic derangements, such as anovulation, hirsutism, and menstrual irregularities. First-line medical therapy usually consists of an oral contraceptive to induce regular menses.

If symptoms such as hirsutism are not sufficiently alleviated, an androgen-blocking agent may be added. First-line treatment for ovulation induction when fertility is desired are letrozole or clomiphene citrate. [4, 5, 7]

-

Medications used in the management of PCOS include the following:

-

Oral contraceptive agents (eg, ethinyl estradiol, medroxyprogesterone)

-

Antiandrogens (eg, spironolactone, leuprolide, finasteride)

-

Hypoglycemic agents (eg, metformin, insulin)

-

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (eg, clomiphene citrate)

-

Topical hair-removal agents (eg, eflornithine)

-

Topical acne agents (eg, benzoyl peroxide, tretinoin topical cream (0.02–0.1%)/gel (0.01–0.1%)/solution (0.05%), adapalene topical cream (0.1%)/gel (0.1%, 0.3%)/solution (0.1%), erythromycin topical 2%, clindamycin topical 1%, sodium sulfacetamide topical 10%)

Surgery

Surgical management of PCOS is aimed mainly at restoring ovulation. Various laparoscopic methods include the following:

-

Electrocautery

-

Laser drilling

-

Multiple biopsy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The major features of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) include menstrual dysfunction, anovulation, and signs of hyperandrogenism. [3] Although the exact etiopathophysiology of this condition is unclear, PCOS can result from abnormal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. A key characteristic of PCOS is inappropriate gonadotropin secretion, which is more likely a result of, rather than a cause of, ovarian dysfunction. In addition, one of the most consistent biochemical features of PCOS is a raised plasma testosterone level. [8] (See Etiology and Workup.)

Stein and Leventhal were the first to recognize an association between the presence of polycystic ovaries and signs of hirsutism and amenorrhea (eg, oligomenorrhea, obesity). [9] After women diagnosed with Stein-Leventhal syndrome underwent successful wedge resection of the ovaries, their menstrual cycles became regular, and they were able to conceive. [10] As a consequence, a primary ovarian defect was thought to be the main culprit, and the disorder came to be known as polycystic ovarian disease. (See Etiology and Treatment.)

Further biochemical, clinical, and endocrinologic studies revealed an array of underlying abnormalities. As a result, the condition is now referred to as PCOS, although it may occur in women without ovarian cysts and although ovarian morphology is no longer an essential requirement for diagnosis.

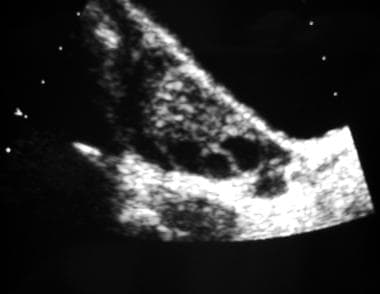

A woman is diagnosed with polycystic ovaries (as opposed to PCOS) if she has 20 or more follicles in at least 1 ovary—measuring 2-9 mm in diameter—or a total ovarian volume greater than 10 cm3. [2] (See the image below.) (See Workup.)

Longitudinal transabdominal ultrasonogram of an ovary. This image reveals multiple peripheral follicles.

Longitudinal transabdominal ultrasonogram of an ovary. This image reveals multiple peripheral follicles.

Diagnostic criteria

A 1990 expert conference sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Disease (NICHD) of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS:

-

Oligo-ovulation or anovulation manifested by oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea

-

Hyperandrogenism (clinical evidence of androgen excess) or hyperandrogenemia (biochemical evidence of androgen excess)

-

Exclusion of other disorders that can result in menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism

In 2003, the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) recommended that at least 2 of the following 3 features are required for PCOS to be diagnosed [11] :

-

Oligo-ovulation or anovulation manifested as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea

-

Hyperandrogenism (clinical evidence of androgen excess) or hyperandrogenemia (biochemical evidence of androgen excess)

-

Polycystic ovaries (as defined on ultrasonography)

A research analysis by Copp et al pointed out that since the expanded criteria for PCOS diagnosis from the Rotterdam consensus, the estimated number of diagnoses in women of reproduction age increased from 4-6.6% to 21%. [12, 13]

The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (AE-PCOS) published a position statement in 2006 [14] and its criteria in 2009 [15] emphasizing that, in the society’s opinion, PCOS should be considered a disorder of androgen excess, as defined by the following:

-

Clinical/biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism

-

Evidence of ovarian dysfunction (oligo-ovulation and/or polycystic ovaries)

-

Exclusion of related disorders

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) indicated that a diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of at least 2 of the following 3 criteria, when congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumors, or Cushing syndrome have been excluded [4] :

-

Oligo-ovulation or anovulation

-

Clinical/biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism

-

Polycystic ovaries on ultrasonograms (>12 small antral follicles in an ovary)

Etiology

Women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) have abnormalities in the metabolism of androgens and estrogen and in the control of androgen production. High serum concentrations of androgenic hormones, such as testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), may be encountered in these patients. However, individual variation is considerable, and a particular patient might have normal androgen levels.

PCOS is also associated with peripheral insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, and obesity amplifies the degree of both abnormalities. Insulin resistance in PCOS can be secondary to a postbinding defect in insulin receptor signaling pathways, and elevated insulin levels may have gonadotropin-augmenting effects on ovarian function. Hyperinsulinemia may also result in suppression of hepatic generation of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), which in turn may increase androgenicity. [16]

In addition, insulin resistance in PCOS has been associated with adiponectin, a hormone secreted by adipocytes that regulates lipid metabolism and glucose levels. Lean and obese women with PCOS have lower adiponectin levels than do women without PCOS. [17]

A proposed mechanism for anovulation and elevated androgen levels suggests that, under the increased stimulatory effect of luteinizing hormone (LH) secreted by the anterior pituitary, stimulation of the ovarian theca cells is increased. These cells, in turn, increase the production of androgens (eg, testosterone, androstenedione). Because of a decreased level of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) relative to LH, the ovarian granulosa cells cannot aromatize the androgens to estrogens, which leads to decreased estrogen levels and consequent anovulation. Growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF-1) may also augment the effect on ovarian function. [18]

Hyperinsulinemia is also responsible for dyslipidemia and for elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) in patients with PCOS. Elevated PAI-1 levels are a risk factor for intravascular thrombosis.

Polycystic ovaries are enlarged bilaterally and have a smooth, thickened capsule that is avascular. On cut sections, subcapsular follicles in various stages of atresia are seen in the peripheral part of the ovary. The most striking ovarian feature of PCOS is hyperplasia of the theca stromal cells surrounding arrested follicles. On microscopic examination, luteinized theca cells are seen.

Some evidence suggests that patients have a functional abnormality of cytochrome P450c17, the 17-hydroxylase, which is the rate-limiting enzyme in androgen biosynthesis. [17]

PCOS is a genetically heterogeneous syndrome in which the genetic contributions remain incompletely described. PCOS is an inherently difficult condition to study genetically because of its heterogeneity, difficulty with retrospective diagnosis in postmenopausal women, associated subfertility, incompletely understood etiology, and gene effect size. [8] Many published genetics studies in PCOS have been underpowered, and the results of published candidate gene studies have been disappointing.

Studies of family members with PCOS indicate that an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance occurs for many families with this disease. The fathers of women with PCOS can be abnormally hairy; female siblings may have hirsutism and oligomenorrhea; and mothers may have oligomenorrhea. [19] Research has suggested that in a large cohort of women with PCOS, a family history of type 2 diabetes in a first-degree family member is associated with an increased risk of metabolic abnormality, impaired glucose tolerance, and type II diabetes. [19] In addition, a Dutch twin-family study showed a PCOS heritability of 0.71 in monozygotic twin sisters, versus 0.38 in dizygotic twins and other sisters. [20]

An important link between PCOS and obesity was corroborated genetically for the first time by data from a case-control study in the United Kingdom that involved 463 patients with PCOS and more than 1300 female controls. [21] The investigators demonstrated that a variant within the FTO gene (rs9939609, which has been shown to predispose to common obesity) was significantly associated with susceptibility to the development of PCOS.

Wickenheisser et al reported that CYP17 promoter activity was 4-fold greater in cells of patients with PCOS. This research suggests that the pathogenesis of PCOS may be in part related to the gene regulation of CYP17. [22] However, in a study that assessed candidate genes for PCOS using microsatellite markers to look for association in 4 genes— CYP19, CYP17, FST, and INSR —only 1 marker near the INSR gene was found to be significantly associated with PCOS. [23] The authors concluded that a susceptibility locus for PCOS (designated PCOS1) exists in 19p13.3 in the INSR region, but it cannot be concluded that the INSR gene itself is responsible. [23]

Subsequent studies have found additional associations, such as those of 15 regions in 11 genes previously described to influence insulin resistance, obesity, or type 2 diabetes. [24] Individuals with PCOS were found more likely to be homozygous for a variant upstream of the PON1 gene and homozygous for an allele of interest in IGF2. Interestingly, the PON1 gene variant resulted in decreased gene expression, which could increase oxidative stress. The exact result of the IGF2 variant is unclear, but IGF2 stimulates androgen secretion in the ovaries and adrenal glands. [24]

In study by Goodarzi et al, the leucine allele was found to be associated with protection against PCOS, as compared to the valine allele at position 89 in SRD5A2. [25] The leucine allele is associated with a lower enzyme activity. [25] When the results of this study are combined with those of an observational study by Vassiliadi et al, based on urinary steroid profiles in women with PCOS, further support can be found for an important role for 5-alpha reductase in the pathogenesis of this syndrome. [26]

In a genome-wide association study for PCOS in a Han Chinese population, 3 strong regions of association were identified, at 2p16.3, 2p21, and 9q33.3. [27] The polymorphism most strongly associated with PCOS at the 2p16 locus was near several genes involved in proper formation of the testis, as well as a gene that encodes a receptor for luteinizing hormone (LH) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). This polymorphism was also located 211kb upstream from the FSHR gene, which encodes the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor. [27]

The polymorphisms most strongly associated with PCOS at the 2q21 locus encode a number of genes, including the THADA gene, which has previously been associated with type 2 diabetes. In addition, 6 significant polymorphisms were identified as being associated with PCOS at the 9q33.3 locus near the DENND1A gene, which interacts with the ERAP1 gene. Elevation in serum ERAP1 has been previously associated with PCOS and obesity. [27]

Epidemiology

In the United States, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine disorders of reproductive-age women, with a prevalence of 4-12%. [28, 29] Up to 10% of women are diagnosed with PCOS during gynecologic visits. [30] In some European studies, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to be 6.5-8%. [31, 32]

A great deal of ethnic variability in hirsutism is observed. For example, Asian (East and Southeast Asia) women have less hirsutism than white women given the same serum androgen values. In a study that assessed hirsutism in southern Chinese women, investigators found a prevalence of 10.5%. [33] In hirsute women, there was a significant increase in the incidence of acne, menstrual irregularities, polycystic ovaries, and acanthosis nigricans. [33]

PCOS affects premenopausal women, and the age of onset is most often perimenarchal (before bone age reaches 16 y). However, clinical recognition of the syndrome may be delayed by failure of the patient to become concerned by irregular menses, hirsutism, or other symptoms or by the overlap of PCOS findings with normal physiologic maturation during the 2 years after menarche. In lean women with a genetic predisposition to PCOS, the syndrome may be unmasked when they subsequently gain weight. [16]

Prognosis

Evidence suggest that women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may be at increased risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Women with hyperandrogenism have elevated serum lipoprotein levels similar to those of men. [34, 35, 36, 37]

Approximately 40% of patients with PCOS have insulin resistance that is independent of body weight. These women are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and consequent cardiovascular complications.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology recommend screening for diabetes by age 30 years in all patients with PCOS, including obese and nonobese women. [38] In patients at particularly elevated risk, testing before 30 years of age may be indicated. Patients who initially test negative for diabetes should be periodically reassessed throughout their lifetime.

Patients with PCOS are also at an increased risk for endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. [6, 39] The chronic anovulation in PCOS leads to constant endometrial stimulation with estrogen without progesterone, and this increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends induction of withdrawal bleeding with progestogens a minimum of every 3-4 months. [6]

No known association with breast or ovarian cancer has been found; thus, no additional surveillance is needed. [6]

Patient Education

Discuss with patients the symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) as well as their increased risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Educate women with this condition regarding lifestyle modifications such as weight reduction, increased exercise, and dietary modifications. [4, 5, 6] (See Diet and Activity.)

For more information, see Women's Health Center, as well as Ovarian Cysts, Amenorrhea, and Female Sexual Problems.

-

Longitudinal transabdominal ultrasonogram of an ovary. This image reveals multiple peripheral follicles.

-

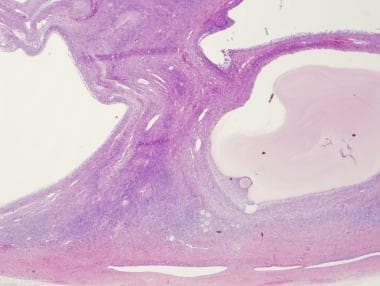

Low power, H and E of an ovary containing multiple cystic follicles in a patient with PCOS.