Practice Essentials

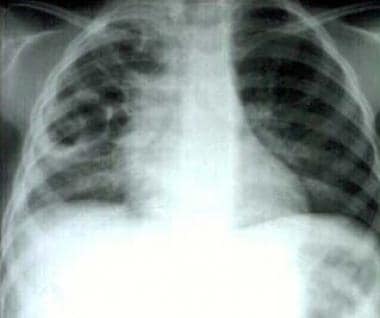

Pulmonary pneumatoceles are thin-walled, air-filled cysts that develop within the lung parenchyma. (See the image below.) In most patients, pneumatoceles are asymptomatic and do not require surgical treatment.

Signs and symptoms

Children present with typical features of pneumonia, including cough, fever, and respiratory distress. Auscultation of the chest reveals focal or bilateral decreased breath sounds. Inspiratory crackles are frequently audible.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies

The following tests can be useful in the workup:

-

Blood culture

-

Sputum culture

-

Pleural fluid culture

Imaging studies

Pneumatoceles are usually evident on chest radiographs by day 5-7 of hospitalization. Chest computed tomography (CT) scanning with contrast is often not necessary to diagnose a pneumatocele, but CT scanning occasionally helps to differentiate an abscess from a pneumatocele.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical care for pneumatocele is treatment of the underlying condition. In most circumstances, this involves administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat the pneumonia. Pneumatoceles almost never require surgical resection.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Pulmonary pneumatoceles can be single emphysematous lesions but are more often multiple, thin-walled, air-filled, cystlike cavities. Most often, they occur as a sequela to acute pneumonia, commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus. However, pneumatocele formation also occurs with other agents, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, group A streptococci, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, adenovirus, and tuberculosis. Pneumatoceles are generally observed soon after the development of pneumonia but can be observed on the initial chest radiograph.

Noninfectious etiologies include hydrocarbon ingestion, trauma, and positive pressure ventilation.

In premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome, pneumatoceles result mostly from ventilator-induced lung injury. [1, 2, 3]

In most circumstances, pneumatoceles are asymptomatic and do not require surgical intervention. [4] Treatment of the underlying pneumonia with antibiotics is the first-line therapy. Close observation in the early stages of the infection and periodic follow-up care until resolution of the pneumatocele is usually adequate treatment. The natural course of a pneumatocele is slow resolution with no further clinical sequelae. Invasive approaches should only be reserved for patients who develop complications.

Pathophysiology

Since the 1950s, multiple theories have been proposed as to the exact mechanism of pneumatocele formation; however, the exact mechanism remains controversial.

Carrey suggested that the initial event is inflammation and narrowing of the bronchus, leading to the formation of an endobronchial ball valve. [5] Ultimately, this bronchial obstruction leads to distal dilatation of the bronchi and alveoli. In 1951, Conway proposed that a peribronchial abscess forms and subsequently ruptures its contents into the bronchial lumen. [6] This also acts similarly to a ball-valve obstruction in the bronchus and leads to distal dilatation. In 1972, Boisset concluded that pneumatoceles are caused by bronchial inflammation that ruptures the bronchiolar walls and causes the formation of "air corridors." [7] Air dissects down these corridors to the pleura and forms pneumatoceles, a form of subpleural emphysema.

Traumatic pneumatocele has a different pathophysiology from the infectious type, [8] developing in a 2-step process. Initially, the lung is compressed by the external force of the trauma, followed by rapid decompression from increased negative intrathoracic pressure. A "bursting lesion" of the lung occurs and leads to pneumatocele formation.

Etiology

Although no particular genetic predisposition is recognized, pneumatocele formation is associated with hyperimmunoglobulin E (IgE) syndrome (Buckley-Job syndrome). [9, 10] Because of immunodeficiency, individuals with this syndrome are predisposed to infection with staphylococcal pneumonia, with the known complications of abscess and pneumatocele formation.

Infectious etiologies associated with pneumatocele formation include the following:

-

S aureus

-

S pneumoniae

-

H influenzae

-

K pneumoniae

-

S marcescens

-

E coli

-

Group A streptococci

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

-

Adenovirus

Noninfectious etiologies include the following:

-

Trauma

-

Hydrocarbon ingestion

-

Positive pressure ventilation (especially among premature infants) [11]

Epidemiology

International statistics

Incidence of postinfectious pneumatocele formation ranges from 2-8% of all cases of pneumonia in children. [12] However, the frequency can be as high as 85% in staphylococcal pneumonias.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No specific racial predilection is observed for pneumatocele formation. Because pneumatoceles are usually a complication of pneumonia, the predilection is based on susceptibility for infection.

No sex predilection is known.

Infants younger than 1 year account for three fourths of the cases of staphylococcal pneumonia. Because pneumatoceles commonly develop as a complication of staphylococcal pneumonia, pneumatoceles are found more frequently in infants and young children. One study reported that 70% of pneumatoceles occurred in children younger than 3 years. [13]

Prognosis

In general, an uncomplicated pneumatocele carries an excellent prognosis. Complete resolution of the pneumatocele is the most common outcome.

Rare complications, including tension pneumatocele, can lead to death from respiratory or cardiovascular collapse from progressive enlargement of the pneumatocele. However, this is rare and, if detected promptly, can be properly treated.

Morbidity/mortality

Although mortality from the initial pneumonia can be significant, mortality associated with pneumatoceles is quite low. Complete resolution without long-term sequelae is typical; however, rare complications can occur, including the following:

-

Tension pneumatocele

-

Secondarily infected pneumatocele

Complications

A tension pneumatocele can develop if airtrapping continues and the pneumatocele expands. This complication occurs most frequently with positive pressure ventilation. If severe, the lesion can cause compression of adjacent structures, with hemodynamic instability and severe airway obstruction. If unrecognized and untreated, this can result in respiratory failure and death.

Pneumothorax can occur from a pneumatocele rupturing into the pleural space. This can lead to collapse of the lung, requiring evacuation of the pleural air to reexpand the lung. A bronchopleural fistula can result as a complication of the pneumothorax.

A pneumatocele can become secondarily infected, usually by a different bacterium from the one that caused the primary pneumonia. Some advocate percutaneous drainage of infected pneumatoceles, especially if fluid- or pus-filled to prevent the development of severe lung abscess that may require surgical excision. Drainage can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. If drained, the fluid should be cultured for bacteria and fungus.

-

Pneumonia with multiple pneumatoceles.

-

Pneumonia with pneumatocele (lateral).

-

Resolving pneumatocele.

-

Chest CT scan of pneumonia with pneumatocele.