Background

Plague, a zoonotic disease caused by the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis, is transmitted to humans by the bites of infected fleas (eg, Xenopsylla cheopis), scratches from infected animals, inhalation of aerosols, or consumption of food contaminated with Y pestis. [1, 2] No disease has impacted civilization as deeply as the plague. As many as 200 million people have died from this disease.

The first pandemic, known as the Justinian plague (AD 541-544), began in Egypt and spread throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean areas. Eventually, the entire known world was affected. By the 8th century, plague receded into scattered endemic areas.

The second pandemic began in 1347, when traders from central Asia introduced plague into ports of Sicily. This became the first epidemic, known as the Black Death, which killed over one third of the population of Europe. Later, following the Great Plague of London (1665), the disease subsided.

The third pandemic began in Hong Kong in 1894 and continues to the present. Alexandre Yersin discovered the plague bacillus, Y pestis, and effective antibiotics were introduced in the early 1940s; however, plague remains endemic in much of the world. [3, 4]

Examples of findings are shown in the images below.

Ecchymoses at the base of the neck in a girl with plague. The bandage is over the site of a prior bubo aspirate. These lesions are probably the source of the line from the children's nursery rhyme, "ring around the rosy." Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Ecchymoses at the base of the neck in a girl with plague. The bandage is over the site of a prior bubo aspirate. These lesions are probably the source of the line from the children's nursery rhyme, "ring around the rosy." Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Acral necrosis of the nose, the lips, and the fingers and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC, US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

Acral necrosis of the nose, the lips, and the fingers and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC, US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

Acral necrosis of the toes and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC: US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

Acral necrosis of the toes and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC: US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

Pathophysiology

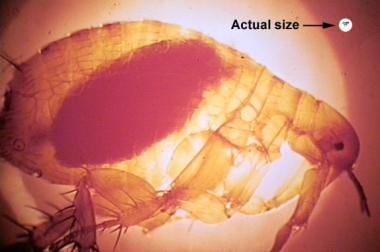

The classic mode of transmission to humans is a flea bite (see the image below).

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

Alternately, broken skin serves as a portal when tissue or blood of an infected animal is handled (skinning or evisceration of infected animals). Competency of the flea to serve as vector for transmission of plague to humans depends on its willingness to feed on a human host and its tendency to regurgitate intestinal contents during a blood meal. Fleas from sylvatic rodents feed on humans only reluctantly. However, the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) is an effective vector because of its tendency to regurgitate and to feed on nonrodent hosts (see the image below).

Male Xenopsylla cheopis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood. This flea is the primary vector of plague in most large plague epidemics in Asia, Africa, and South America. Both male and female fleas can transmit the infection. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Male Xenopsylla cheopis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood. This flea is the primary vector of plague in most large plague epidemics in Asia, Africa, and South America. Both male and female fleas can transmit the infection. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

When the flea takes a blood meal from an infected rodent, stomach enzymes cause a clot to form, blocking the flea's proventricularis. At its next attempt to feed, unable to swallow due to the blockage, the flea regurgitates plague bacilli into the bite wound.

The organisms invade the lymphatics and travel to regional lymph nodes, causing inflammation (see the image below).

After the femoral lymph nodes, the next most commonly involved regions in plague are the inguinal, axillary, and cervical areas. This child has an erythematous, eroded, crusting, necrotic ulcer at the presumed primary inoculation site in the left upper quadrant. This type of lesion is uncommon in patients with plague. The location of the bubo is primarily a function of the region of the body in which an infected flea inoculates plague bacilli. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

After the femoral lymph nodes, the next most commonly involved regions in plague are the inguinal, axillary, and cervical areas. This child has an erythematous, eroded, crusting, necrotic ulcer at the presumed primary inoculation site in the left upper quadrant. This type of lesion is uncommon in patients with plague. The location of the bubo is primarily a function of the region of the body in which an infected flea inoculates plague bacilli. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Large, tender lymph nodes are termed buboes and give the bubonic form of plague its name. If the infection is not contained at this site, the organisms may be further spread via the bloodstream to organs such as lungs, spleen, liver, kidneys, and meninges. Bacteremia without the appearance of buboes is considered septicemic plague. Pneumonic plague occurs when pneumonia results from either hematogenous spread (secondary pneumonic plague) or inhalation (primary pneumonic plague) of organisms transmitted from animals or other humans.

Etiology

Bacteriology

The causative bacterium (Y pestis) was discovered by Yersin in 1894. It is a nonmotile, pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacillus that belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Bipolar staining (giving the appearance of a closed safety pin) can be observed with Giemsa, Wayson, or Wright stains (see the image below).

Wright stain peripheral blood smear of patient with septicemic plague demonstrating bipolar, safety pin staining of Yersinia pestis. Although Wright stain often demonstrates this characteristic appearance, Giemsa and Wayson stains most consistently highlight this pattern. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, CO.

Wright stain peripheral blood smear of patient with septicemic plague demonstrating bipolar, safety pin staining of Yersinia pestis. Although Wright stain often demonstrates this characteristic appearance, Giemsa and Wayson stains most consistently highlight this pattern. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, CO.

It grows at a wide range of temperatures (4-40ºC) but demonstrates optimal growth at room temperature.

Both an endotoxin and an exotoxin are produced, adding to the organism's pathogenicity.

Transmission

Human infection is usually acquired through the bites of infected rodent fleas. X cheopis, the Oriental rat flea, is the classic vector, but many other species of flea are also capable of transmitting plague. Typically, this form of transmission is common in crowded urban areas.

Plague can also be contracted from handling infected animals, especially rodents, lagomorphs (eg, rabbits or hares), and domestic cats, or through close contact with patients with pneumonic plague.

A recent study suggests that lice might play a role in transmission of Y pestis and that preventing and controlling louse infestations might help limit the extension of plague epidemics in louse-infested populations. [5]

Another potential cause of plague transmission in humans is contact with an infected dog. In 2014, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) laboratory isolated Y pestis in a blood specimen from a hospitalized man with pneumonia. Further investigation found that the man’s dog had recently died with hemoptysis and that 3 other persons who came into contact with the dog had respiratory symptoms and fever. Specimens from the dog and the other three persons showed evidence of acute Y pestis infection. One of the transmissions may have been human to human, which would be the first such reported US case since 1924. [6]

Person-to-person transmission is extremely rare. Person-to-person transmission occurs primarily through droplet exposure from a patient with the pneumonic form of the disease, although direct contact with body fluids can also be infectious.

Epidemiology

United States data

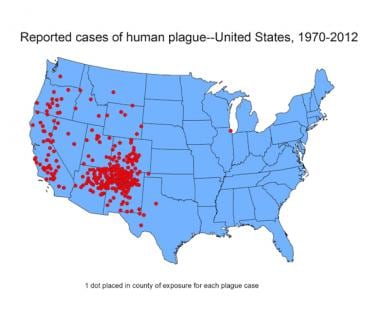

Plague is considered endemic in all western and southwestern states. [7] Most human cases in the United States occur in two regions:

· Northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, and southern Colorado

· California, southern Oregon, and far western Nevada

Most cases of plague are acquired in rural areas. Native Americans who reside on reservations are at increased risk for acquisition of the disease. Ground squirrels and prairie dogs serve as major enzootic foci (see the image below). [8]

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

Dogs and cats are susceptible to plague. Domestic animals, cats in particular, have been responsible for human cases.

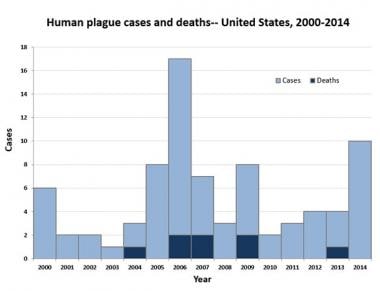

Between 1900 and 2012, 1006 confirmed or probable human plague cases occurred in the United States. Over 80% of United States plague cases have been the bubonic form. During 2001–2012, the annual number of human plague cases reported in the United States ranged from one to 17 (median = three cases). [9, 10]

However, plague activity increased during 2015. In a CDC report published on August 25, 2015, a total of 11 cases of human plague had been reported since April 1, 2015. [11] Affected patients were residents of six states: Arizona (two), California (one), Colorado (four), Georgia (one), New Mexico (two), and Oregon (one). The two cases in Georgia and California residents were linked to exposures at or near Yosemite National Park in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. It is unclear why the number of cases in 2015 is higher than usual.

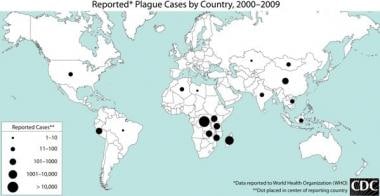

International data

Plague reached a worldwide maximum of 5419 cases (274 fatal) in 1997, and the incidence has declined since that time. [12] In 2003, 9 countries reported 2118 cases (182 fatal) to the World Health Organization (WHO). [13] Algeria reported cases of human plague for the first time in 50 years. India and Indonesia also recently reported cases after a 30-year to 50-year quiescent period. Almost all of the cases reported in the last 20 years have occurred among people living in small towns and villages or agricultural areas rather than in larger towns and cities. Between 1,000 and 2,000 cases each year are reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), though the true number is likely much higher. Occurrence is thought to be underreported. [14, 15] Currently, about 95% of the world’s human plague cases now occur in the African region, including Madagascar. [16] World distribution of plague is shown below.

Sex- and age-related demographics

Plague occurs in both men and women. It is slightly more common among men.

Plague has occurred in people of all ages, although, 50% of cases occur in people aged 12-45 years.

Prognosis

Mortality rate for untreated plague is 40-70%. Untreated pneumonic plague is nearly 100% fatal.

From 1947-1996, reported mortality rate in the United States was 15%.

Because plague is often a difficult disease to consider in the differential diagnosis, many patients who succumb to it have previously sought medical care.

Morbidity/mortality

Bubonic plague

Mortality is approximately 16%, which increases to 40-70% in untreated cases. [17] Practitioners must maintain a high index of suspicion for plague, especially with patients exposed to animals or fleas in endemic areas. The most common complications are secondary septicemia, pneumonia, and meningitis. Polyarthritis, lung abscesses, and superinfection of lymph nodes also rarely occur.

Septicemic plague

Mortality ranges from 30-50% for patients with septicemic plague and increases to nearly 100% in untreated cases. This high mortality rate reflects the difficulty in diagnosis, given the disease's similarity to gram-negative bacterial sepsis. Diagnosis is often made postmortem.

Pneumonic plague

The fatality rate of untreated pneumonic plague approaches 100%. The last reported case of person-to-person transmission occurred during a plague epidemic in Los Angeles in 1924. Since then, cases of primary pneumonic plague have been acquired chiefly from infected cats.

Complications

Complications include the following:

-

Polyarthritis

-

Lung abscesses

-

Suppuration or superinfection of buboes

-

Meningitis

-

Death

-

Male Xenopsylla cheopis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood. This flea is the primary vector of plague in most large plague epidemics in Asia, Africa, and South America. Both male and female fleas can transmit the infection. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

-

Wright stain peripheral blood smear of patient with septicemic plague demonstrating bipolar, safety pin staining of Yersinia pestis. Although Wright stain often demonstrates this characteristic appearance, Giemsa and Wayson stains most consistently highlight this pattern. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, CO.

-

Inguinal bubo on upper thigh of a person with bubonic plague. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

-

Yersinia pestis bacteria on fluorescent antibody test. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

-

Pictured is a flea with a blocked proventriculus, which is equivalent to the gastroesophageal region in a human. In nature, this flea would develop a ravenous hunger because of its inability to digest the fibrinoid mass of blood and bacteria. If this flea were to bite a mammal, the proventriculus would be cleared, and thousands of bacteria would be regurgitated into the bite wound. Courtesy of the United States Army Environmental Hygiene Agency.

-

After the femoral lymph nodes, the next most commonly involved regions in plague are the inguinal, axillary, and cervical areas. This child has an erythematous, eroded, crusting, necrotic ulcer at the presumed primary inoculation site in the left upper quadrant. This type of lesion is uncommon in patients with plague. The location of the bubo is primarily a function of the region of the body in which an infected flea inoculates plague bacilli. Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

Ecchymoses at the base of the neck in a girl with plague. The bandage is over the site of a prior bubo aspirate. These lesions are probably the source of the line from the children's nursery rhyme, "ring around the rosy." Courtesy of Jack Poland, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

Acral necrosis of the nose, the lips, and the fingers and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC, US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

-

Acral necrosis of the toes and residual ecchymoses over both forearms in a patient recovering from bubonic plague that disseminated to the blood and the lungs. At one time, the patient's entire body was ecchymotic. Reprinted from Textbook of Military Medicine. Washington, DC: US Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General, and Borden Institute. 1997:493. Government publication, no copyright on photos.

-

Rock squirrel in extremis coughing blood-streaked sputum related to pneumonic plague. Courtesy of Ken Gage, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Fort Collins, Colo.

-

Reported cases of human plague in US 1970-2012. Courtesy of the CDC.

-

Worldwide distribution of plague cases 2000-2009. Courtesy of the CDC.

-

Human plague cases and deaths in US 2004-2014. Courtesy of the CDC.