Practice Essentials

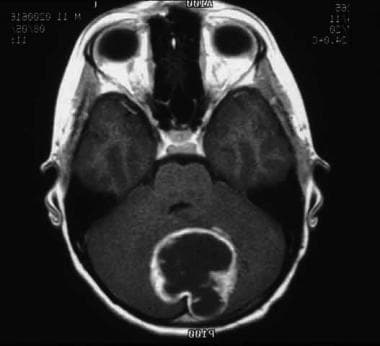

Astrocytoma is the most common brain tumor (see image shown below), accounting for more than half of all primary CNS malignancies in children.

Signs and symptoms of astrocytoma

Initial symptoms are usually nonspecific, nonlocalizing, and related to increased intracranial pressure (ICP). The classic triad of a raised ICP consists of the following:

-

Morning headaches

-

Vomiting

-

Lethargy

School-aged children more commonly report vague intermittent headaches and fatigue. Infants may present with irritability, anorexia, developmental delay, or regression.

Other signs and symptoms are related to the location of the tumor.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of astrocytoma

The following studies are indicated in patients with suspected astrocytoma:

-

Head CT imaging with and without contrast

-

Head and spine MRI with and without gadolinium

CT imaging or MRI must be performed before the lumbar puncture to rule out hydrocephaly in those patients suspected of having a brain tumor. Cerebrospinal fluid cytologic examination is useful in malignant astrocytomas for the detection of microscopic leptomeningeal dissemination.

See Workup for more detail.

Management of astrocytoma

Treatment of astrocytomas depends on the location and grade of the tumor. Tumor location and associated morbidity may limit resection or render the tumor inoperable.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Brain tumors comprise approximately 20% of all childhood malignancies, second only to acute lymphoblastic leukemia in frequency. Astrocytomas comprise a wide range of neoplasms that differ in their extent of invasiveness, morphological features, tendency for progression, and clinical course. The most widely accepted grading schema for astrocytomas is the World Health Organization [WHO] that assigns a grade from I to IV based on the degree of anaplasia of tumor cells, proliferation index values and genetic alterations. WHO grade I tumors include pilocytic astrocytomas and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas. WHO grade II tumors include diffuse astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas. WHO grade III tumors include anaplastic astrocytomas and anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas. WHO grade IV tumors include glioblastoma multiforme and diffuse midline gliomas. [1]

Most astrocytomas are indolent low-grade (ie, WHO grade I-II) tumors for which surgical resection alone is sufficient to cure. The prognosis decreases for low-grade tumors in unresectable locations and remains very poor for high-grade astrocytomas in spite of the addition of radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Pathophysiology

Pilocytic astrocytomas (ie, WHO grade I) arise throughout the neuraxis, but preferred sites include the optic nerve, optic chiasm/hypothalamus, thalamus and basal ganglia, cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, and brain stem. These tumors show low cellularity, low proliferative and mitotic activity, and rarely metastasize or undergo malignant transformation. In general, they do not aggressively infiltrate surrounding tissue and regressive changes in long-standing lesions are common. These tumors are the principle CNS neoplasm of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMA) is a recently defined variant of pediatric low-grade astrocytoma. PMAs have been classified with pilocytic astrocytomas but have been found to have different histologic features and to behave more aggressively than pilocytic astrocytomas. PMAs have a tendency to disseminate and, in some reports, have a worse prognosis compared with pilocytic astrocytomas.

Diffuse astrocytomas (ie, WHO grade II) may arise in any area of the CNS but most commonly develop in the cerebrum, particularly the frontal and temporal lobes. The brain stem and spinal cord are the next most frequently affected sites, whereas the cerebellum is a distinctly uncommon site. These tumors are moderately cellular, infiltrative, and often enlarging, which distorts but does not destroy neighboring anatomical structures. Mitotic activity is generally absent.

Anaplastic astrocytoma (ie, WHO grade III) arises in the same locations as diffuse astrocytomas, with a preference for the cerebral hemispheres. These tumors show increased cellularity, distinct nuclear atypia, marked mitotic activity, and a tendency to infiltrate through neighboring tissue.

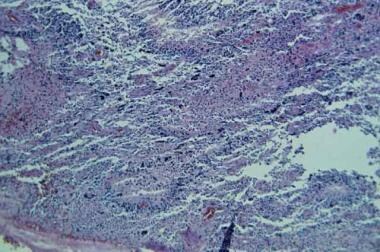

Glioblastoma multiforme (ie, WHO grade IV) tumors occur most often in the subcortical white matter of the cerebral hemispheres. Combined frontotemporal location with infiltration into the adjacent cortex, basal ganglia, and contralateral hemisphere is typical. Glioblastoma is the most frequent tumor of the brain stem in children, while the cerebellum and spinal cord are rare sites. These tumors are highly cellular, with high proliferative and mitotic activity. Although rapid and extensive invasion of surrounding tissue is common, distant metastasis within or outside the CNS is rare. Refer to the image below.

This section displays a typical field of a glioblastoma multiforme (grade IV) with pseudopalisading neovascularity, nuclear atypia, numerous mitoses, and areas of hemorrhage.

This section displays a typical field of a glioblastoma multiforme (grade IV) with pseudopalisading neovascularity, nuclear atypia, numerous mitoses, and areas of hemorrhage.

Increasing evidence indicates that the differences between the clinicopathologic entities of astrocytomas (ie, WHO grades I-IV) reflect specific genetic alterations. [2, 3] Recent studies show that the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas possess a characteristic BRAF–KIAA1549 gene fusion. [4, 5] Additional mutations found in low-grade gliomas include BRAFV600E and NF1. Mutations in TP53, EGFR, H3K27M, PDGFRA and PTEN are found in high-grade astrocytomas (WHO grade III and IV).

Etiology

Epidemiologic studies investigating parental occupational exposure, environmental exposure, and maternal nutritional intake failed to identify linkages with any of the childhood brain tumors.

An association with NF1 is present in 50-80% of patients with isolated optic nerve astrocytomas and in as many as 20% of those with chiasmal or deeper optic tract tumors. NF1 and tuberous sclerosis are also associated with other low-grade astrocytomas. Twenty percent of children with NF1 have low-grade gliomas, especially visual pathway tumors.

Astrocytoma is the most frequent CNS tumor in people with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome (germline mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene on the short arm of chromosome 17).

Ionizing radiation to the head for prior malignancies causes secondary supratentorial malignant astrocytomas in a small number of patients.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Astrocytoma is the most common brain tumor of childhood. Researchers report that the annual incidence is approximately 14 new cases per million children younger than 15 years.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No specific racial predisposition is observed. An analysis of 2000-2017 data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program found that the overall incidence of astrocytomas was lower in Hispanic children than in non-Hispanic White children. [6]

The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:1, except for supratentorial low-grade gliomas, in which it is approximately 2:1.

Most cases occur in the first decade of life, with the peak incidence occurring in children aged 5-9 years. High-grade supratentorial tumors occur slightly later, with a median age at diagnosis of 9-10 years.

Prognosis

Low-grade astrocytoma

The 10-year survival rate for completely resected low-grade cerebellar astrocytomas is near 100%, with little or no morbidity. It is 60-95% for all low-grade tumors, including those incompletely resected and treated with radiotherapy.

Supratentorial tumors may result in residual motor deficits or seizure disorder. Radiotherapy may lead to neurocognitive impairment, neuroendocrine dysfunction, or ischemia and infarct.

High-grade astrocytoma

Those who survive (< 30%) are often left with some degree of motor, neurocognitive, or endocrinologic dysfunction.

Astrocytoma of the brain stem

Patients with dorsal exophytic and cervicomedullary tumors treated by complete surgical resection have survival rates of more than 90%.

Survival may be 50-100% for those with small focal tumors of the midbrain or tectal region treated with surgery and/or radiotherapy. In sharp contrast, patients with diffuse pontine lesions rarely survive.

Surgery to these areas can result in paralysis of multiple cranial nerves, mutism, and a compromised respiratory effort.

Astrocytoma of the visual pathway

The 10-year survival rate for patients with intracranial tumors (chiasm or deeper) is 40-85%, in contrast to the 90-100% for those with intraorbital tumors.

Fewer than half of all patients have improvement in their visual deficits noted at diagnosis.

As many as 50% of prepubertal children develop endocrinologic dysfunction from radiotherapy.

Astrocytoma of the spinal cord

The overall survival rate for patients with low-grade astrocytomas with various degrees of resection and postoperative radiotherapy is 67% at 20 years, whereas those with high-grade tumors rarely survive.

Khelifa-Gallois et al conducted a study of functional outcomes in adolescents and adults who were treated for a low-grade cerebellar astrocytoma in childhood. [7] The study cohort consisted of 18 adolescents and 46 adults. Data regarding academic achievement, professional status, and neurologic, cognitive and behavioral disturbances were collected through the use of self-completed and parental questionnaires for adolescents and of phone interviews for adults. For the adolescents, a control group filled in the same questionnaires. Mean time of lapse from surgery was 7.8 years for adolescents and 12.9 years for adults. Five adults (11%) had major sequelae related to postoperative complications, postoperative mutism, and/or brain stem involvement. For all the other participants reported cognitive difficulties and difficulties related to mild neurologic sequelae (ie, fine motor skills, balance) although academic achievement was similar to that of control participants. The investigators concluded that long-term functional outcomes of patients with low-grade cerebellar astrocytoma are generally favorable in the absence of postoperative complications and brain stem involvement. [7]

Morbidity/mortality

In low-grade astrocytomas, complete surgical resection is associated with 5-year survival rates as high as 95-100% without further treatment. Patients with subtotal resections may have only a 60-80% survival rate over similar periods; however, after partial resection, long-term progression-free intervals may ensue. Current operative mortality rates are less than 1%. Morbidity depends largely on tumor location and is highest in diencephalic tumors, in which the incidence of hemiparesis or visual field deficits may be 10-20%. Cortical-based tumors may be associated with seizures.

In high-grade astrocytomas, the most recent 5-year survival rate is 15-30% for supratentorial lesions and less than 10% for pontine tumors. Neurologic morbidity, such as neurocognitive impairment, neuroendocrinologic deficiency, motor and coordination impairment, and cranial nerve dysfunction may occur from tumor invasion, surgical resection, and/or treatment with radiation and chemotherapy. Seizure disorders may develop depending on the tumor location.

Complications

Complications of astrocytomas include the following:

-

Obstructive hydrocephaly

-

Neurologic impairment

-

Radiation-induced effects

Neurocognitive decline

Endocrinologic dysfunction

Mineralizing microangiopathy with ischemia or infarct

Secondary CNS malignancies

Transient headaches, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia

-

Chemotherapy-induced effects

Myelosuppression, infection, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, renal damage, hepatic damage, hearing damage, neurotoxicity, and secondary malignancies may occur.

Investigational chemotherapy for either high-grade or low-grade tumors may cause complications such as fever, neutropenia, or suspected infection; therefore, hospitalization may be necessary.

Infertility and impairment of growth may also be long-term sequelae of therapy.

Patient Education

Refer patients and their family members for psychosocial counseling.

The following patient education resources are available from WebMD:

-

This MRI shows a pilocytic astrocytoma of the cerebellum.

-

This MRI shows a supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme.

-

This section displays the typical biphasic pattern of a pilocytic astrocytoma, consisting of dense, relatively anuclear, fibrillar areas alternating with looser cystic fields.

-

This section displays the high cellularity, mitosis, and nuclear atypia characteristic of an anaplastic astrocytoma (grade III).

-

This section displays a typical field of a glioblastoma multiforme (grade IV) with pseudopalisading neovascularity, nuclear atypia, numerous mitoses, and areas of hemorrhage.