Practice Essentials

Myelofibrosis (bone marrow fibrosis) is characterized by the presence of excessive collagen and reticulin fibers in bone marrow. In most patients, it arises secondary to other disease processes. Pediatric myelofibrosis is uncommon; much of what is known about it is extrapolated from the adult literature or reported from isolated cases in children. See the image below.

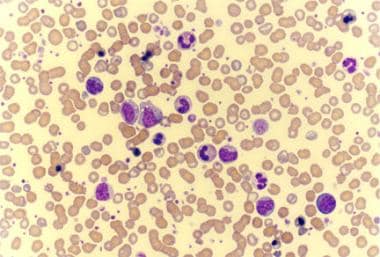

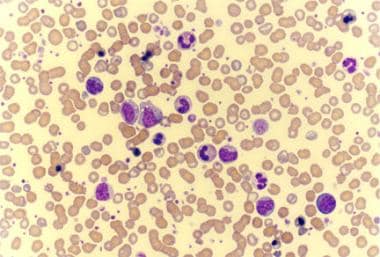

Photomicrograph of a peripheral smear of a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (idiopathic myelofibrosis) shows findings of leukoerythroblastosis, giant platelets, and few teardrop cells.

Photomicrograph of a peripheral smear of a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (idiopathic myelofibrosis) shows findings of leukoerythroblastosis, giant platelets, and few teardrop cells.

Signs and symptoms of myelofibrosis

Patients with a condition predisposing to myelofibrosis present with a history of that disease. There may be a family history or a history of exposure to ionizing radiation. A detailed family history may identify an affected relative.

Clinical symptoms may be mild; some patients are asymptomatic at presentation. Manifestations of disease may include, but are not limited to, the following:

-

Pallor (anemia)

-

Bruising, petechiae, or bleeding (thrombocytopenia)

-

Fever

-

Weight loss

-

Night sweats

-

Bone pain

-

Left upper quadrant pain

-

Splenomegaly (frequent), hepatomegaly, or lymphadenopathy [1]

-

Stigmata of a predisposing condition

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of myelofibrosis

Laboratory testing may include the following:

-

Evaluation for peripheral blood abnormalities (eg, normocytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or leukocytosis with left shift)

-

Endocrinologic testing (eg, hyper- or hypoparathyroidism)

-

Rheumatologic evaluation

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine testing (to rule out renal dysfunction)

-

Coombs (direct antiglobulin) test

-

Purified protein derivative (PPD) test

-

Chromosomal analysis in any child with onset before age 2 years

The following imaging studies may be helpful:

-

Abdominal ultrasonography

-

Abdominal computed tomography (CT)

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Other studies include the following:

-

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy

-

Cytogenetic analysis (to exclude myeloid neoplasms)

See Workup for more detail.

Management of myelofibrosis

When secondary childhood myelofibrosis is identified, treatment should be directed at the underlying process.

Supportive care of myelofibrosis typically includes the following:

-

Transfusions (red blood cells [RBCs] or platelets)

-

Prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in some patients with neutropenia

-

Aggressive treatment of fever and suspected infections

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin and bisphosphonates in selected cases

Medications that may be helpful include the following:

-

Corticosteroids

-

Interferon alfa

-

Hydroxyurea

-

Thalidomide and lenalidomide

-

Vitamin D

-

Decitabine

-

Janus kinase inhibitors (eg, ruxolitinib)

Other treatment measures that may be considered include the following:

-

Radiotherapy

-

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

-

Splenectomy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Bone marrow fibrosis, known as myelofibrosis, was originally described in 1879 and is characterized by the presence of excessive collagen and reticulin fibers in bone marrow. This is an uncommon condition in children, and much of what is known is extrapolated from the adult literature or reported from isolated pediatric cases.

In most patients, the condition arises secondary to other disease processes. [2] In particular, myelofibrosis is frequently associated with malignancy (eg, acute megakaryoblastic leukemia [AMKL]). (See Clinical and Workup.)

Myelofibrosis may be observed prior to a clear diagnosis of acute leukemia [3] at the time of diagnosis of leukemia, [4] or as a late event in patients previously treated for leukemia. Numerous nonmalignant conditions have also been reported in association with myelofibrosis. (See Treatment.)

Importantly, primary or idiopathic myelofibrosis (IMF) is also described. [5, 6, 7]

Note the image below.

Photomicrograph of a peripheral smear of a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (idiopathic myelofibrosis) shows findings of leukoerythroblastosis, giant platelets, and few teardrop cells.

Photomicrograph of a peripheral smear of a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (idiopathic myelofibrosis) shows findings of leukoerythroblastosis, giant platelets, and few teardrop cells.

Complications

Patients can be expected to develop complications secondary to decreased production of functional white blood cells (infection), decreased numbers of red blood cells (anemia), and decreased numbers of platelets (bleeding).

Splenomegaly may lead to hypersplenism, thereby worsening cytopenias.

There is an increased risk of myelodysplasia and myeloid leukemia.

A single case report described subcutaneous lymphoma arising in a child with IMF. [8]

See Prognosis.

Patient education

Early onset myelofibrosis is occasionally inherited in a recessive pattern. Counsel parents about the possibility of a second affected child.

Pathophysiology

In normal marrow, the fine fibrous collagen network is faintly perceptible after conventional staining techniques with silver impregnation. Although not unique to this condition, increased staining is a hallmark of myelofibrosis.

The fibrous network observed in myelofibrosis is collagenous. Collagen types I, III, IV, and V are increased, with the most significant increased noted in type III. Fibrosis of the bone marrow presumably reflects overgrowth of the normal marrow matrix. [9] This can be observed in association with several diseases and has even been reported to have prognostic significance in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. [10] Overgrowth has been shown to be related to the secretion of profibrotic cytokines and myeloproliferative growth factors. [11]

In cases of acute myelofibrosis of childhood (C-AMF), myelofibrosis may be secondary to the release of granules by abnormal megakaryocytes. In addition to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), these granules contain transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b) and epidermal growth factor (EGF), both of which can stimulate proliferation of fibroblasts. TGF-b synthesis appears to be regulated by nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kB). Interestingly, the overexpression of an immunophilin, FK506-binding protein 51, has been observed in myelofibrosis megakaryocytes, and this protein appears, in turn, to activate NF-kB. [12]

Matrix homeostasis results from a balance between the deposition of the matrix and its removal. The former is regulated by various growth factors, most notably PDGF, whereas the latter presumably reflects the activity of collagenase-expressing monocytes, macrophages, and granulocytes. Thus, the diseases associated with myelofibrosis can be classified according to whether the basic defect is matrix overproduction, underresorption, or both.

Marrow blood flow and microvessel density are also increased in patients with myelofibrosis, most likely due to an increase in circulating endothelial cell progenitors.

Some investigators believe that the abnormal fibrotic marrow stroma directly enhances the circulation and dissemination of hematopoietic precursors. [13] This leads to extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, or (occasionally) kidneys, causing myeloid metaplasia in these organs, which then become enlarged. Hypersplenism, if present, exacerbates cytopenias.

The gain-of-function V617F mutation in the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene (on 9p) is seen in many adult patients with IMF. [14] Its presence correlates with a shift from thrombopoiesis toward increased erythropoiesis and may also predict progression to massive splenomegaly and leukemic transformation. [15, 16]

Among adults with IMF, conventional cytogenetic analysis of the marrow reveals an abnormal clone in approximately one third of patients. Using a comparative genomic hybridization technique, Al-Assar et al studied IMF marrow specimens and found chromosomal imbalances in 21 of 25 cases. [17] Gains of 9p, 13q, 2q, 3p, and 12q were among the most commonly seen abnormalities. Isolated del(20q) or del(13q) appears to confer a better prognosis. All other abnormalities confer an independent adverse effect on survival and are also associated with higher JAK2V617F mutational frequency. [18]

A study by Livun et al suggested that in primary myelofibrosis, several genes related to bone marrow homeostasis are aberrantly expressed, with the investigators finding upregulation of cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX2) and down-regulation of chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4), paired box 5 (PAX5) C-terminus, and hypoxia inducible factor 1A (HIF1A). [19]

Predisposing conditions

Classification of myelofibrosis includes the following: primary (idiopathic) C-AMF, secondary (malignant) C-AMF, and secondary (nonmalignant) C-AMF.

Causes of secondary (malignant) C-AMF include:

-

Acute erythroblastic (M6) leukemia [20]

-

Acute megakaryoblastic (M7) leukemia (AMKL)

-

ALL [21]

-

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

-

Essential thrombocythemia [22]

-

Hodgkin disease (reported cases in adults only)

Causes of secondary (nonmalignant) C-AMF include:

-

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

-

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [23]

-

Sickle cell anemia (a single case report) [24]

-

Fanconi anemia

-

Vitamin D deficiency

-

Renal osteodystrophy

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus [28]

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Gray platelet syndrome

-

Osteopetrosis

-

Hyperparathyroidism

-

Hypoparathyroidism (reported cases in adults only)

-

Pernicious anemia (reported cases in adults only)

-

Gaucher disease (reported cases in adults only)

-

Exposure to radiation, thorium dioxide, benzene (reported cases in adults only)

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Approximately 100 cases of pediatric myelofibrosis have been reported worldwide. This is likely an underrepresentation, because cases associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (the most common association) are not generally reportable.

International occurrence

Cases of pediatric myelofibrosis have been described in association with tuberculosis (in Pakistan) and visceral leishmaniasis (in Sudan). Thus, myelofibrosis is presumably more common in areas of endemicity for these diseases. Detailed epidemiologic data are not available. Autosomal recessive familial myelofibrosis appears to be more common among children from Saudi Arabia. [29, 30, 31]

Sex- and age-related demographics

In published cases of pediatric myelofibrosis, females outnumber males by a ratio of approximately 2:1.

In infants, the presentation may be atypical and lack some of the classic clinical features.

A large percentage of published cases of pediatric myelofibrosis occurs in children younger than 3 years. These younger patients are more likely to have Down syndrome, rickets, or a familial (possibly autosomal recessive) form of myelofibrosis. Among older patients, AML, systemic lupus erythematosus, and tuberculosis are the most common associations.

Prognosis

The prognosis of childhood myelofibrosis varies depending on the clinical context in which it occurs. With appropriate treatment for rickets, tuberculosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other conditions, the myelofibrosis may completely resolve.

Idiopathic acute myelofibrosis of childhood may be a fulminant disease. Without effective therapy, life expectancy is typically less than 1 year. Potentially effective and/or curative treatments include chemotherapy and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Treatment with medications may also result in a temporary amelioration of the disease. Occasionally, pediatric patients have a more indolent course than what is observed in adults. With supportive care alone, they may survive for many years.

In adult patients with myelofibrosis, several alternative prognostic scoring systems (PSSs) are available. [32, 33] Neither the patient's symptoms nor the percentage of circulating blasts is taken into account in the Mayo Clinic PSS (in contrast to other PSSs). A retrospective review of 334 patients with myelofibrosis showed the Mayo Clinic PSS to be more effective than other PSSs in terms of (1) identifying long-lived patients and (2) delineating an intermediate-risk disease category. [33] The Mayo PSS assigns a score of 1-4 by allotting 1 point for each of the following:

-

Hemoglobin level more than 10 g/dL

-

White blood cell (WBC) count less than 4 or more than 30 X 109/L

-

Platelet count less than 100 X 109/L

-

Absolute monocyte count at or above 1 X 109/L

A new prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis has been determined based on data collected during a study conducted by the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. [34]

Multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors:

-

Age older than 65 years

-

Constitutional symptoms

-

Hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL

-

Circulating blast cells 1% or greater

Pediatric patients were included in this study but not in sufficient numbers to analyze as a separate group.

Morbidity and mortality

Myelofibrosis causes, or accompanies conditions that cause, disruption of normal hematopoiesis. Patients may experience anemia, neutropenia, and/or thrombocytopenia. Patients may also experience pain secondary to hepatosplenomegaly. Neutropenia may lead to opportunistic infections. Thrombocytopenia may lead to hemorrhage.

In a study of 15 cases of pediatric idiopathic myelofibrosis, Mishra et al reported that 14 of the patients (93%) presented with transfusion-dependent anemia. In addition, findings included myeloid hyperplasia (13 patients, 87%); megakaryocytic hyperplasia (10 patients, 67%); dysmegakaryopoiesis (8 patients, 53%); small, loose megakaryocytic clustering (3 patients, 20%); and leukoerythroblastosis with dacryocytes (1 patient, 7%). [35]

-

Photomicrograph of a peripheral smear of a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (idiopathic myelofibrosis) shows findings of leukoerythroblastosis, giant platelets, and few teardrop cells.