Practice Essentials

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by an intracellular protozoan parasite (genus Leishmania) transmitted by the bite of a female phlebotomine sandfly. The clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis ranges from a self-resolving cutaneous ulcer to a mutilating mucocutaneous disease and even to a lethal systemic illness. Therapy has long been a challenge in the more severe forms of the disease, and it is made more difficult by the emergence of drug resistance. With the exception of Australia, the Pacific Islands, and Antarctica, the parasites have been identified throughout large portions of the world.

Classification

The taxonomy of Leishmania organisms is complex, and no single categorization is generally accepted. The 2 simplest and most widely used systems for categorizing leishmaniasis are as follows:

-

Categorization by clinical disease: In this system, leishmaniasis is divided into 3 primary clinical forms: cutaneous (localized, diffuse (disseminated), leishmaniasis recidivans, post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis), mucocutaneous , and visceral (kala-azar or black-fever in hindi ) and viscerotropic

-

Categorization by geographic occurrence: In this system, disease is divided into (1) Old World leishmaniasis (caused by Leishmania species found in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and India), which produces cutaneous or visceral disease, and (2) New World leishmaniasis (caused by Leishmania species found in Central and South America), which produces cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease

Signs and symptoms

Cutaneous leishmaniasis includes the following features:

-

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis: Crusted papules or ulcers on exposed skin; lesions may be associated with sporotrichotic spread

-

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis: Multiple, widespread nontender, nonulcerating cutaneous papules and nodules; analogous to lepromatous leprosy lesions

-

Leishmaniasis recidivans: Presents as a recurrence of lesions at the site of apparently healed disease years after the original infection, typically on the face and often involving the cheek; manifests as an enlarging papule, plaque, or coalescence of papules that heals with central scarring (ie, lesions in the center or periphery of an old healed leishmaniasis scar); relentless expansion at the periphery may cause significant facial destruction similar to the lupus vulgaris variant of cutaneous tuberculosis

-

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: Develops months to years after the patient's recovery from visceral leishmaniasis, with cutaneous lesions ranging from hypopigmented macules to erythematous papules and from nodules to plaques; the lesions may be numerous and persist for decades

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis consists of the relentless destruction of the oropharynx and nose, resulting in extensive midfacial destruction. Specific signs and symptoms include the following:

-

Excessive tissue obstructing the nares, septal granulation, and perforation; nose cartilage may be involved, giving rise to external changes known as parrot's beak or camel's nose

-

Possible presence of granulation, erosion, and ulceration of the palate, uvula, lips, pharynx, and larynx, with sparing of the bony structures; hoarseness may be a sign of laryngeal involvement

-

Gingivitis, periodontitis

-

Localized lymphadenopathy

-

Optical and genital mucosal involvement in severe cases

Visceral and viscerotropic leishmaniasis include the following features:

-

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar): Potentially lethal widespread systemic disease characterized by darkening of the skin as well as the pentad of fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and hypergammaglobulinemia

-

Viscerotropic leishmaniasis: Nonspecific abdominal tenderness, fever, rigors, fatigue, malaise, nonproductive cough, intermittent diarrhea, headache, arthralgias, myalgias, nausea, adenopathy, and transient hepatosplenomegaly

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis of leishmaniasis can include the following:

-

Isolation, visualization, and culturing of the parasite from infected tissue

-

Serologic detection of antibodies to recombinant K39 antigen

-

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for sensitive, rapid diagnosis of Leishmania species

Other tests that may be considered include the following:

-

CBC count, coagulation studies, liver function tests, peripheral blood smear

-

Measurements of lipase, amylase, gamma globulin, and albumin

-

Leishmanin (Montenegro) skin testing (LST) (not FDA approved in the United States)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment is tailored to the individual, because leishmaniasis is caused by many species or subspecies of Leishmania.

Pharmacologic therapies include the following:

-

Pentavalent antimony (sodium stibogluconate or meglumine antimonate): Used in cutaneous leishmaniasis; not marketed in the United States, but available through the CDC under an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol

-

Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome): Effective against pentavalent antimony ̶ resistant mucocutaneous disease and visceral leishmaniasis

-

Oral miltefosine (Impavido): Approved by the FDA in March 2014 for visceral leishmaniasis due to L donovani; cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis, L guyanensis, and L panamensis; and mucosal leishmaniasis due to L braziliensis

-

Intramuscular pentamidine: Effective against visceral leishmaniasis but associated with persistent diabetes mellitus and disease recurrence

-

Orally administered ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, allopurinol, and dapsone: None is as effective as the pentavalent antimony compounds, but they may be useful in accelerating cure in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis that does not progress to mucosal disease and tends to self-resolve

-

Topical paromomycin: Shown to be effective against cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L major and L mexicana

-

Sitamaquine: Undergoing phase 3 trials

Local therapies for some forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis include the following:

-

Cryotherapy

-

Local heat therapy at 40-42°C

Other important issues in the management of leishmaniasis are as follows:

-

Correction of malnutrition

-

Treatment of concurrent systemic illness (eg, HIV disease or tuberculosis)

-

Control of local infection

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by an intracellular protozoa parasite transmitted by the bite of a female sandfly (Phlebotomus species). The clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis ranges from a self-resolving, localized cutaneous ulcer to widely disseminated progressive lesions of the skin, to a mutilating mucocutaneous disease, and even to a lethal systemic illness that affects the reticuloendothelial system.

This condition affects as many as 12 million people worldwide, with 900,000 to 1.3 million new cases each year. The global incidence of leishmaniasis has increased in recent years due to increased international leisure- and military-related travel, human alteration of vector habitats, and concomitant factors that increase susceptibility, such as infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malnutrition. With the exception of Australia, the Pacific Islands, and Antarctica, the parasites have been identified throughout large portions of the world.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

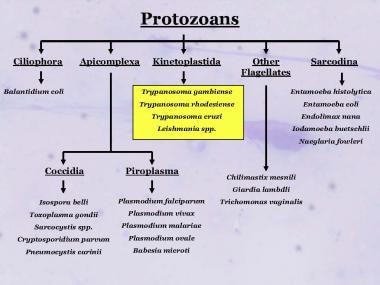

The taxonomy of Leishmania organisms is complex, and no single categorization is generally accepted.

Taxonomy of some of the medically important protozoans showing the relative relationship of the Kinetoplastida parasites generally, and Leishmania specifically.

Taxonomy of some of the medically important protozoans showing the relative relationship of the Kinetoplastida parasites generally, and Leishmania specifically.

The 2 simplest and most widely used disease categorization systems are based on clinical disease and geographic occurrence, as follows:

-

Clinical disease: The primary clinical forms of leishmaniasis are cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease; cutaneous manifestations can be further subdivided into localized, diffuse (disseminated), recidivans, and post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

-

Geographic occurrence: Old World leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania species found in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and India, and it produces cutaneous or visceral disease; New World leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania species found in Central America and South America, and it produces cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease. Diagnosis of leishmaniasis often is difficult because of the small size of the protozoa sequestered within macrophages of the skin, bone marrow, and reticuloendothelial system.

Therapy has long been a challenge in the more severe forms of the disease, and it is made more difficult by the emergence of drug resistance. No effective vaccine for leishmaniasis is available.

Pathophysiology

Modes of transmission

In leishmaniasis, the obligatory intracellular protozoa are transmitted to mammals via the bite of the tiny 2- to 3-mm female sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus in the Old World (Eastern Hemisphere) and Lutzomyia in the New World (Western Hemisphere).

The bite of 1 infected sandfly is sufficient to cause the disease, because a sandfly can egest more than 1000 parasites per bite. Traditionally divided between Old World and New World parasites, more than 20 pathogenic species of Leishmania have been identified [1] ; about 30 of the 500 known phlebotomine sandfly species have been positively identified as vectors of the disease. [2]

The sandfly usually is one half to one third the size of a mosquito (see the image below). Leishmaniasis infections are considered zoonotic diseases, because for most species of Leishmania, an animal reservoir is required for endemic conditions to persist. Humans are generally considered incidental hosts. Infections in wild animals are usually not pathogenic, with the exception of dogs, which may be severely affected.

Comparison of a sandfly (left) and a mosquito (right). The sandfly's small size affects the efficacy of bed nets when used without permethrin treatment.

Comparison of a sandfly (left) and a mosquito (right). The sandfly's small size affects the efficacy of bed nets when used without permethrin treatment.

Common Old World hosts are domestic and feral dogs, rodents, foxes, jackals, wolves, raccoon-dogs, and hyraxes. Common New World hosts include sloths, anteaters, opossums, and rodents. The reservoir of infection for Indian kala-azar is humans, whereas it is rodents for African kala-azar, foxes in Brazil and Central Asia, and canines for the Mediterranean and Chinese kala-azar. Other mammalian reservoirs for the Leishmania parasite include equines and monkeys.

Uncommon modes of transmission include congenital transmission, contaminated needle sticks, blood transfusion, sexual intercourse, and, rarely, inoculation of cultures. Although clear documentation of the potential of transfusion-associated leishmaniasis exists, there is less certainty of clear documentation of the actual occurrence of transfusion-related disease, because most cases in the literature occur in endemic areas of the world. [3, 4]

In India, visceral leishmaniasis caused by L donovani does not appear to have an animal reservoir and is thought to be transmitted via human-sandfly-human interaction.

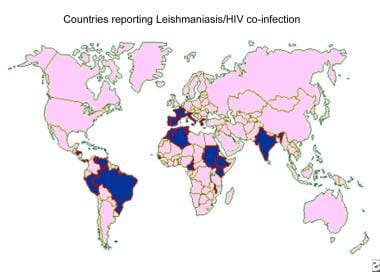

Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has led to the spread of leishmaniasis, typically a rural disease, into urban areas. In patients infected with HIV, leishmaniasis accelerates the onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) by cumulative immunosuppression and by stimulating the replication of the virus. It may also change asymptomatic Leishmania infections into symptomatic infections. Sharing of needles by intravenous drug users can spread not only HIV but also leishmaniasis.

Leishmania life cycle

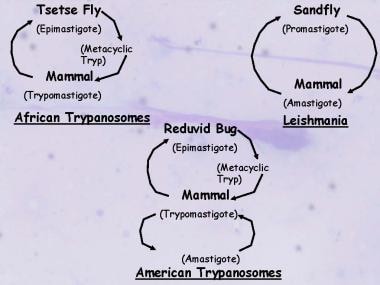

The parasites exist in the flagellated promastigote stage in sandflies and in artificial culture and then transform into the nonflagellated amastigote form in animal and human hosts.

Life cycles of the medically important Kinetoplastida illustrating the similarities and differences between the trypanosomes and Leishmania.

Life cycles of the medically important Kinetoplastida illustrating the similarities and differences between the trypanosomes and Leishmania.

Only the female sandfly transmits the protozoan, infecting itself with the Leishmania parasites contained in the blood it sucks from its human or mammalian host. Over 4-25 days, the parasite continues its development inside the sandfly, where it undergoes a major transformation into the promastigote form. A large number of flagellate forms (promastigotes) are produced by binary fission. Multiplication proceeds in the mid gut of the sandfly, and the flagellates tend to migrate to the pharynx and buccal cavity of the sandfly. A heavy pharyngeal infection is observed between Days 6 and 9 of an infected blood meal. The promastigotes are regurgitated via a bite during this period, resulting in the spread of leishmaniasis.

Following the bite, some of the flagellates that enter the new host’s circulation are destroyed, whereas others enter the intracellular lysosomal organelles of macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system, where they lose their flagella and change into the amastigote form (see the first image below). The amastigote forms also multiply by binary fission, with multiplication continuing until the host cell is packed with the parasites and ruptures, liberating the amastigotes into the circulation (see the second image below). The free amastigotes then invade fresh cells, thus repeating the cycle and, in the process, infecting the entire reticuloendothelial system. Some of the free amastigotes are drawn by the sandfly during its blood meal, thus completing the cycle.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

Depending on the species of parasite and the host’s immune status, the parasites may incubate for weeks to months before presenting as skin lesions or as a disseminated systemic infection involving the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Temperature is an important factor that helps determine the localization of leishmanial lesions. Species causing visceral leishmaniasis are able to grow at core temperatures, whereas those responsible for cutaneous leishmaniasis grow best at lower temperatures. Pathogenesis appears related to T-cell cytotoxicity.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by L tropica; an animal reservoir for leishmaniasis caused by this organism has not been identified, although it has been found in some dogs in endemic areas. Morphologically, it is indistinguishable from L donovani. The life cycle is exactly the same as that of L donovani except that the amastigote form resides in the large mononuclear cells of the skin.

Pathogenesis

After inoculation by sandflies, the flagellated promastigotes bind to macrophages in the skin. Two of the parasite surface molecules appear to play a prominent role in parasite-phagocyte interactions. The extent and presentation of disease depend on several factors, including the humoral and cell-mediated immune response of the host, the virulence of the infecting species, and the parasite burden. Infections may heal spontaneously or may progress to chronic disease, often resulting in death from secondary infection.

Promastigotes activate complement through the alternate pathway and are opsonized. The most important immunologic feature is a marked suppression of the cell-mediated immunity to leishmanial antigens. In persons with asymptomatic self-resolving infection, T-helper (Th1) cells predominate, with interleukin 2 (IL-2), interferon-gamma, and IL-12 as the prominent cytokines that induce disease resolution, although immune suppression years later can result in disease. An overproduction of both specific immunoglobulins and nonspecific immunoglobulins also occurs. The increase in gamma globulin leads to a reversal of the albumin-globulin ratio commonly associated with this disease.

As noted earlier, leishmaniasis involves the reticuloendothelial system. Parasitized macrophages disseminate infection to all parts of the body but more so to the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. The spleen is enlarged, with a thickening of the capsule, and is soft and fragile; its vascular spaces are dilated and engorged with blood. The reticular cells of Billroth are markedly increased and packed with the amastigote forms of the parasite. However, no evidence of fibrosis is present. In the liver, the Kupffer cells are increased in size and number and infected with amastigote forms of Leishmania. Bone marrow turns hyperplastic, and parasitized macrophages replace the normal hemopoietic tissue.

With visceral or diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous disease, patients exhibit relative anergy to the Leishmania organism and have a prominent Th2 cytokine profile. Typically, visceral leishmaniasis incubates for weeks to months before becoming clinically apparent. The disease can be subacute, acute, or chronic, and can manifest in patients who are immunocompromised years after they have left endemic regions.

In addition, susceptibility genes in band 22q12 have been found in an ethnic group in parts of Sudan that has a high prevalence rate of visceral leishmaniasis.

Etiology

Risk factors

Poverty and malnutrition play a major role in the increased susceptibility to leishmaniasis. Extracting timber, mining, building dams, widening areas under cultivation, creating new irrigation schemes, expanding road construction in primary forests such as the Amazon, continuing widespread migration from rural to urban areas, and continuing fast urbanization worldwide are among the primary causes for increased exposure to the sandfly.

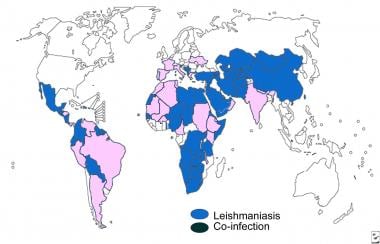

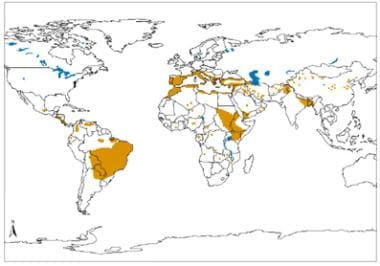

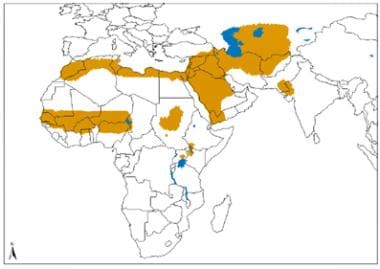

Geographical distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in the Old and New world. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/.

Geographical distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in the Old and New world. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/.

Another risk factor is the movement of susceptible populations into endemic areas, including large-scale migration of populations for economic reasons. In the city of Kabul, Afghanistan, which has a population of less than 2 million, an estimated 270,000 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis occurred in 1996. The resurgence of visceral leishmaniasis has occurred because of deficiencies in the control of the vector (sandfly), absence of a vaccine, and lack of access to medical treatment due to cost and increasing drug resistance to first-line treatment.

Coexistence of leishmaniasis with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a serious concern. Leishmaniasis is spreading in several areas of the world because of the rapid dissemination of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic. The immune deficiency has led to increased susceptibility to infections, including leishmaniasis: Persons with AIDS are at 100-1000 times greater risk of developing visceral leishmaniasis in certain areas. Thus far, co-infections have been reported in 33 countries worldwide.

Children are at greater risk than adults in endemic areas. Incomplete therapy of the initial disease is a risk factor for recurrence.

Commonly associated parasite species and their geographic distribution are summarized below.

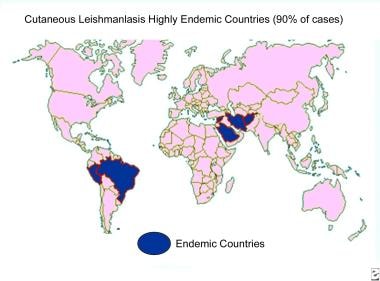

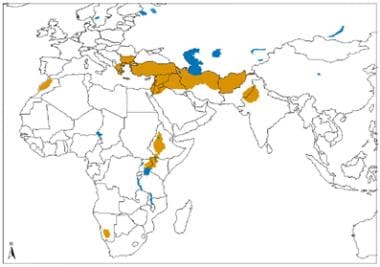

Distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis

Old World spread of localized cutaneous disease includes the following Leishmania species:

-

L donovani - China, India, Bangladesh, Sudan

-

L tropica - Middle East, China, India, Mediterranean

-

L aethiopica - Ethiopia, Kenya, Namibia

-

L major - Middle East, Africa, India, Asia

-

L infantum - Asia, Africa, Europe

Old World spread of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is via L aethiopica in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Namibia.

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L tropica and related species and L aethiopica. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L tropica and related species and L aethiopica. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L major. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html.

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L major. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html.

New World spread of localized cutaneous disease includes the following Leishmania species:

-

L mexicana - Central, South, and North America

-

L amazonensis - Dominican Republic, Central and South America

-

L venezuelensis - Venezuela

-

L (Viannia) braziliensis - Central and South America

-

L (Viannia) guyanensis - Guyana, French Guyana, Surinam, Brazil

-

L (Viannia) panamensis - Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador

-

L (Viannia) peruviana - Peru, Argentina

-

L donovani chagasi - Texas, Caribbean, Central and South America

New World spread of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is via (1) L mexicana in Central, South, and North America, (2) L amazonensis in the Dominican Republic and Central and South America, and (3) L venezuelensis in Venezuela.

Leishmaniasis recidivans

A relatively uncommon clinical variant of leishmaniasis, leishmaniasis recidivans appears as a recurrence of lesions at the site of apparently healed disease years after the original infection.

Old World spread of leishmaniasis recidivans is via L tropica in the Middle East, China, India, and the Mediterranean. New World spread of leishmaniasis recidivans is via L (Viannia) braziliensis in Central and South America.

Post–kala-azar leishmaniasis

The term kala-azar—which means black (kala) fever (azar) in Hindi—is reserved for severe (advanced) cases of visceral leishmaniasis, although the terms kala-azar and visceral leishmaniasis sometimes are used interchangeably. [2]

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) is a syndrome characterized by skin lesions that develop at variable intervals after (or during) therapy for visceral leishmaniasis. [2] This condition is best described in cases of L donovani infection in South Asia and East Africa. In general, post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis is more common, develops earlier, and is less chronic in patients in East Africa. [2]

Old World spread of post–kala–azar leishmaniasis is via the following:

-

L donovani - China, India, and Bangladesh

-

L infantum - Asia, Africa, and Europe

-

New World spread of post–kala–azar leishmaniasis is via L donovani chagasi in Central and South America.

Distribution of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Old World spread of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is via L aethiopica in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Namibia.

New World spread of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis includes the following Leishmania species:

-

L (Viannia) braziliensis - Central and South America

-

L (Viannia) panamensis - Central and South America

-

L (Viannia) guyanensis - Guyana, French Guyana, Surinam, and Brazil

-

Less often seen with L mexicana - Central, South, and North America

-

Less often seen with L amazonensis - Brazil and Panama

Geographical distribution of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in the New World. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/

Geographical distribution of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in the New World. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/

Distribution of visceral leishmaniasis

Old World spread of visceral leishmaniasis is via the following:

-

L donovani - China, India, Bangladesh, Sudan, and Kenya

-

L infantum - Asia, North Africa, and South Europe

-

(Rarely) L tropica - Iran and Kenya

New World spread of visceral leishmaniasis is via L donovani chagasi in Central and South America.

Distribution of viscerotropic leishmaniasis

Old World spread of viscerotropic leishmaniasis is via L tropica in the Middle East.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Endemic leishmaniasis is uncommon in the United States. Although sandflies are found as far north as upstate New York, and visceral leishmaniasis has been identified in foxhounds in a wide geographic distribution in the United States, virtually no human transmission is believed to occur in the majority of the United States.

Periodic, isolated cases of localized and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis have been reported in areas bordering Mexico, such as southern Texas, Oklahoma, [5, 6] and Pennsylvania, with no associated travel outside the patient’s home. The usual reservoir is the wood rat of the Southern Plains, but parasites have been identified in coyotes and domesticated dogs and cats. Spread by the sandfly vector Lutzomyia anthophora, leishmaniasis cases are usually associated with exposure to the habitat of the wood rat.

There were 2 cases of L mexicana cutaneous leishmaniasis described at the end of 2009 and none after that year. Per the WHO Global Health Observatory Data Repository, no new cases of visceral leishmaniasis have been reported since 2005.

Most of the cases of leishmaniasis found in the United States are acquired elsewhere: US travelers, government workers, graduate students, Peace Corps workers, and military personnel are at risk overseas. Between 1985 and 1990, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was notified of 129 cases involving travelers from the United States who acquired the disease abroad.

During World War II, more than 1000 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis were reported among US service members serving in the Persian Gulf. Illnesses now attributed to leishmaniasis have been identified throughout military campaigns from World War I back to antiquity.

During the first Persian Gulf War, an estimated 400 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis and 12 cases of viscerotropic leishmaniasis were reported. [7] The etiologic agent for most of the cutaneous leishmaniasis cases appears to have been L major. Since 2001, more than 700 US military personnel have been diagnosed with cutaneous leishmaniasis and 4 with visceral leishmaniasis after serving in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan led to approximately 2000 laboratory-confirmed cases (and at least double the number of unconfirmed cases) of cutaneous leishmaniasis and 5 laboratory-confirmed cases of visceral leishmaniasis in American soldiers alone from 2003-2008. [8, 9] More than 500 cases of leishmaniasis were diagnosed over an 18-month period in soldiers returning to the United States from the Middle East, especially from Iraq. A large portion of these was identified as cutaneous leishmaniasis. Up to 1% of US forces serving in the Southwest Asian Theater may have been infected. [10]

International statistics

Geographic distribution of leishmaniasis is generally restricted to tropical and temperate regions (natural habitats of the sandfly), and it is limited by the sandfly’s susceptibility to cold climates, its tendency to take blood from humans or animals only, and its capacity to support the internal development of specific species of Leishmania. With the increase in international travel, immigration, overseas military exercises, and coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), leishmaniasis is becoming more prevalent throughout the world.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports endemic leishmaniasis in 98 countries and 3 territories on 5 continents (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, South America), with an official estimated annual incidence of 0.7-1.3 million cases of cutaneous disease and 0.2-0.4 million cases of visceral disease. [11]

Approximately 95% of cases of cutaneous disease occur in the Americas, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East, and Central Asia. More than two thirds of these cases are reported in 6 countries, including Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, Iran, and Syria. Over 90% of new cases of visceral leishmaniasis occur in 6 countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan, and Sudan. [11] India has the largest burden of visceral leishmaniasis, with 13,869 new cases reported in 2013. [12]

The visceral leishmaniasis control program has achieved significant gains in Southeast Asia, with the incidence declining to 10,209 cases in 2014, which is approximately 75% lower than in 2005, when the Kala-Azar control program was launched. In this region, the disease is on the verge of being removed from the Public Health Problem list. [13]

Almost 90% of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis cases occur in Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru. [11]

In Colombia, the military fighting the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) saw more than 30,000 cases of leishmaniasis over 3-year period.

Countries and/or regions not considered to have endemic leishmaniasis despite being surrounded by regions that do include Australia and the South Pacific, Chile, Uruguay, and Canada.

Visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in patients with AIDS have been increasingly appreciated as a potential opportunistic infection. Coinfection with HIV has been reported in more than 35 countries throughout southern Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, Central and South America, and India. [14] Disease occurs in conjunction with severe immunosuppression. The incidence of coinfection has decreased in developed countries because of the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy.

Racial, sexual, and age-related differences in incidence

Although no racial preferences are recognized or described for leishmaniasis, some minor associations with various racial groups have been noted. However, but those data are confounded by and result more strongly in association with occupational exposure

Males have an increased incidence of infection, about double that of females. The higher rates of infection in men, particularly visceral leishmaniasis, may be from increased environmental exposure to the habitat of the sandfly through occupation and leisure activity.

Leishmaniasis affects various age groups, depending on the infecting species, geographic location, disease reservoir, and host immunocompetence. Individuals at the extremes of age may be less able to mount effective immune responses to infection and therefore manifest clinical disease more often, especially seen in association with visceral leishmaniasis.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis affects all age groups. Reports from Afghanistan and Colombia show that adolescents and young adults are at risk the most. In Iran, most cases of the disease are found in infants.

Visceral leishmaniasis is found in all age groups in India and Brazil, where an animal reservoir has not been identified. In areas with known animal reservoirs, such as the Mediterranean Basin, visceral leishmaniasis mainly affects children, with devastating outcomes (eg, L infantum primarily affects children aged 1-4 y). This apparent predilection for the young appears to occur in highly endemic areas because of what may be protective immunity reducing the risk for reinfection in adults. Untreated visceral leishmaniasis in a pregnant individual can also have consequences on the fetus or result in congenital visceral leishmaniasis.

Prognosis

Generally, the prognosis depends on the nutritional and overall immune status of the host, the precise species of infection, as well as appropriate therapy.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis often spontaneously resolves in 3-6 months without therapy, although some infections persist indefinitely. Most individuals respond exceedingly well to therapy: Rapid, complete resolution of the lesion(s), with decreased potential for secondary bacterial infections and diminished scarring, is the rule. This is not to say that the disease is without morbidity, especially in areas where even minimal facial disfiguring can condemn young girls to life without the prospect of marriage or acceptance in society.

Most cases of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, and leishmaniasis recidivans are chronic and resistant to treatment. These forms can be exceedingly disfiguring cosmetically because of the degree of persistent involvement; however, they are associated with low mortality rates.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is chronic and progressive. This form of the disease affects the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and soft palate, and it is especially debilitating and destructive, resulting in extensive midfacial mutilation. Death can occur from secondary infection and after respiratory tract mucosal invasion. Respiratory compromise and dysphagia may lead to malnutrition and pneumonia.

The general consensus is that less than 5% of individuals infected by L brasiliensis, and a smaller percentage of individuals infected by L panamensis and L guyanensis, develop mucosal metastases several months to years after the apparent resolution of cutaneous disease. However, no rigorous studies prove this commonly accepted rate.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis is a serious, progressive, and potentially lethal systemic disease. It tends to affect individuals in poor states of health, with poor nutritional status, and with even the most minor decreased immune status much more severely than individuals with good health, good nutritional status, and intact immune systems.

In well-nourished individuals with intact immune systems, full recovery from visceral disease is expected after treatment with the appropriate medication. With early therapy and supportive care, mortality in patients with visceral disease is reduced to approximately 5%; without therapy, most patients with visceral disease (kala-azar) (75-95%) die within 2 years, often from malnutrition and secondary infection, such as bacterial pneumonia, septicemia, dysentery, tuberculosis, cancrum oris, and uncontrolled hemorrhage or its sequelae.

In some endemic regions, pentavalent antimonial resistance is causing increased mortality rates.

Complications

Complications of leishmaniasis occur as a consequence of anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. They may include the following:

-

Secondary bacterial infection, including pneumonia and tuberculosis

-

Septicemia

-

Disfigurement of nose, lips, and palate (eg, cancrum oris)

-

Uncontrolled bleeding

-

Splenic rupture

-

Late stages: Edema, cachexia, and hyperpigmentation

-

Metastatic lesions in the nasopharynx with tissue destruction

Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can complicate cases of visceral leishmaniasis. A well-described and feared interaction is kala-azar in combination with HIV infection, which leads to more severe and rapidly progressive fatal outcomes from both diseases acting synergistically.

Patient Education

Behavior modification to avoid vector contact, combined with insect control measures, significantly diminishes the risk of acquiring infection.

Educate patients about (1) the possibility of recurrent disease, and instruct them to schedule follow-ups as needed; (2) the transmission of leishmaniasis; and (3) the risk factors of leishmaniasis, including the following:

-

Exposure to sandfly habitat

-

Age (depending on the infecting species and geographic area)

-

Male sex

-

Adults who are immunologically naïve and entering an endemic area

-

Patients who are immunosuppressed (eg, transplant recipients, chronic steroid users, those with malignancies)

-

Malnutrition

-

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

-

Intravenous drug use in endemic areas

-

Classic Leishmania major lesion from a case in Iraq shows a volcanic appearance with rolled edges.

-

Atypical appearance of Leishmania major lesion with local spread beyond the borders of the primary lesion. Many of the lesions in cases from Iraq show an atypical appearance.

-

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

-

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

-

Active cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion with likely secondary infection in a soldier.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis with keloid formation in a black soldier.

-

Taxonomy of some of the medically important protozoans showing the relative relationship of the Kinetoplastida parasites generally, and Leishmania specifically.

-

Leishmania donovani is one of the main Leishmania species that infects humans.

-

Life cycles of the medically important Kinetoplastida illustrating the similarities and differences between the trypanosomes and Leishmania.

-

Distribution map of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

-

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L tropica and related species and L aethiopica. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html

-

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L major. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html.

-

Geographical distribution of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in the New World. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/

-

Geographical distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in the Old and New world. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: http://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/.

-

Distribution map of visceral leishmaniasis.

-

Distribution map of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and leishmaniasis coinfection.

-

The predominant mode of leishmaniasis transmission is a sandfly's bite.

-

Sandfly. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Comparison of a sandfly (left) and a mosquito (right). The sandfly's small size affects the efficacy of bed nets when used without permethrin treatment.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis with sporotrichotic spread.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is generally considered to be an innocuous disease; however, in some parts of the world, especially in tribal areas, even cutaneous disease can have a life altering effect on a person's life. Minimal facial disfiguring can condemn young girls to life without the prospect of marriage or acceptance in society.

-

Leishmaniasis in an Ethiopian woman with a 1-year history of asymptomatic pink-erythematous infiltrative plaque with overlying scale and central crust.

-

Healed cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

-

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Jacinto Convit, National Institute of Dermatology in Caracas, Venezuela.

-

Leishmaniasis recidivans. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

-

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Visceral leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Marked splenomegaly (enlargement/swelling of the spleen) in a patient in lowland Nepal who has visceral leishmaniasis. (Credit: C. Bern, CDC) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/.

-

Amastigotes in a macrophage at 1000× magnification. Inset shows the cell membrane and points out the nucleus and kinetoplast, which are required to confirm that the inclusion seen in a macrophage is indeed an amastigote.

-

Free amastigotes near a disrupted macrophage. On touch preparations like this (Giemsa stain, original magnification × 1000), the amastigotes are easier to identify than on other preparations. These stains clearly demonstrate the cell membrane, nucleus, and kinetoplast; all 3 are required for definitive diagnosis.

-

Free amastigote in a touch preparation (Giemsa stain, original magnification × 1000).

-

Light-microscopic examination of a stained bone marrow specimen from a patient with visceral leishmaniasis—showing a macrophage (a special type of white blood cell) containing multiple Leishmania amastigotes (the tissue stage of the parasite). Note that each amastigote has a nucleus (red arrow) and a rod-shaped kinetoplast (black arrow). Visualization of the kinetoplast is important for diagnostic purposes, to be confident the patient has leishmaniasis. (Credit: CDC/DPDx) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/

-

Illustration of one form of the rK39 test for the serologic diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. It is an easy, very sensitive, and specific test for visceral disease. In this case, the dipstick second from the left shows a positive result and all the rest show reaction only at the control line.