Practice Essentials

In pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), immaturity of lower esophageal sphincter function is manifested by frequent transient lower esophageal relaxations, which result in retrograde flow of gastric contents into the esophagus.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux are most often directly related to the consequences of emesis (eg, poor weight gain) or result from exposure of the esophageal epithelium to the gastric contents. The typical adult symptoms (eg, heartburn, vomiting, regurgitation) cannot be readily assessed in infants and children.

Pediatric patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease typically cry and show sleep disturbance and decreased appetite. Other common signs and symptoms in infants and young children include the following:

-

Typical or atypical crying and/or irritability

-

Apnea and/or bradycardia

-

Poor appetite; weight loss or poor growth (failure to thrive)

-

Apparent life-threatening event

-

Vomiting

-

Wheezing, stridor

-

Abdominal and/or chest pain

-

Recurrent pneumonitis

-

Sore throat, hoarseness and/or laryngitis

-

Chronic cough

-

Water brash

-

Sandifer syndrome (ie, posturing with opisthotonus or torticollis)

Signs and symptoms in older children include all of the above plus heartburn and a history of vomiting, regurgitation, unhealthy teeth, and halitosis.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Most cases of pediatric gastroesophageal reflux are diagnosed based on the clinical presentation. Conservative measures can be started empirically. However, if the presentation is atypical or if therapeutic response is minimal, further evaluation via imaging is warranted.

There are no recognized classic physical signs of gastroesophageal reflux in the pediatric population. Some findings may include the following:

-

Nonverbal infant: Crying and irritability, failure to thrive, hiccups, sleep disturbances, Sandifer syndrome (arching)

-

Toddlers and older children: Significant dental problems from excessive regurgitation, causing acid effects on tooth enamel

Procedures

The following procedures are used to visually assess the esophagus and stomach:

-

Esophageal manometry

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Biopsies may also be performed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy for histopathologic evaluation.

Imaging studies

Radiologic studies used to evaluate pediatric gastroesophageal reflux include the following:

-

Upper gastrointestinal imaging series

-

Gastric scintiscan study

-

Esophagography

Physiologic and electrophysiologic studies

The following studies are used to detect gastroesophageal reflux:

-

Intraesophageal pH probe monitoring: Criterion standard for quantifying gastroesophageal reflux

-

Intraluminal esophageal electrical impedance: For detecting acid and nonacid reflux by measuring retrograde flow in the esophagus; normal values have not been determined in the pediatric age group.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The goals of medical therapy in gastroesophageal reflux are to decrease acid secretion and, in many cases, to reduce gastric emptying time.

Nonpharmacotherapy

Conservative measures in treating children with gastroesophageal reflux include the following [1] :

-

Providing small, frequent feeds thickened with cereal

-

Upright positioning after feeding

-

Elevating the head of the bed

-

Prone positioning (infants >6 months)

Older children with gastroesophageal reflux may benefit from the following:

-

Diet that avoids tomato and citrus products, fruit juices, peppermint, chocolate, and caffeine-containing beverages

-

Smaller, more frequent feeds

-

Relatively lower fat diet (lipids retard gastric emptying)

-

Proper eating habits

-

Weight loss

-

Avoidance of alcohol and tobacco, when applicable

For patients who fail medical therapy, continuous intragastric administration of feeds alone (via nasogastric tube) may be used as an alternative to surgery. [2]

Pharmacotherapy

The following medications are used in pediatric patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease:

-

Antacids (eg, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide)

-

Histamine H2 antagonists (eg, nizatidine, cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine)

-

Proton pump inhibitors (eg, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, [3] dexlansoprazole, rabeprazole sodium, pantoprazole)

No currently available prokinetic drug (eg, metoclopramide) has been demonstrated to exert a significant influence on the number or frequency of reflux episodes.

Surgical option

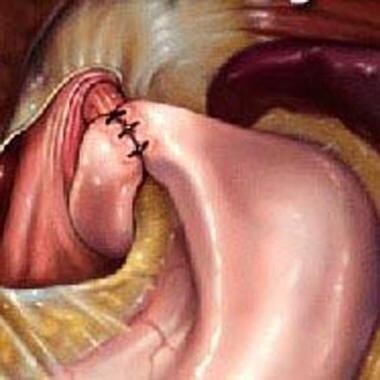

Surgical intervention such as gastrostomy or fundoplication (see the image below) is required in only a very small minority of patients with gastroesophageal reflux (eg, when rigorous medical step-up therapy has failed or when the complications of gastroesophageal reflux pose a short- or long-term survival risk). The goal of surgical antireflux procedures is to "tighten" the region of the lower esophageal junction and, if possible, to reduce hiatal herniation of the stomach (occasionally seen in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease).

Illustration of the Nissen fundoplication. Note how the stomach is wrapped around the esophagus (360-degree wrap).

Illustration of the Nissen fundoplication. Note how the stomach is wrapped around the esophagus (360-degree wrap).

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Gastroesophageal reflux represents the most common gastroenterologic disorder that leads to referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist during infancy. In pediatric gastroesophageal reflux, immaturity of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) function is manifested by frequent transient lower esophageal relaxations (tLESRs), which result in retrograde flow of gastric contents into the esophagus. (See Etiology and Pathophysiology.)

Although minor degrees of gastroesophageal reflux are noted in children and adults, the degree and severity of reflux episodes are increased during infancy. Thus, gastroesophageal reflux represents a common physiologic phenomenon in the first year of life. As many as 60-70% of infants experience emesis during at least 1 feeding per 24-hour period by age 3-4 months. (See Epidemiology and Prognosis.)

The distinction between this "physiologic" gastroesophageal reflux and "pathologic" gastroesophageal reflux in infancy and childhood is determined not merely by the number and severity of reflux episodes (when assessed by intraesophageal pH monitoring), but also, and most importantly, by the presence of reflux-related complications, including failure to thrive, erosive esophagitis, esophageal stricture formation, and chronic respiratory disease. (See Prognosis, Presentation, and Workup.)

Other complications noted in adults with gastroesophageal reflux, including Barrett esophagus and esophageal mucosal dysplasia, are uncommon in childhood.

Gastroesophageal reflux is classified as follows (see Presentation, Workup, Treatment, and Medication):

-

Physiologic (or functional) gastroesophageal reflux - These patients have no underlying predisposing factors or conditions; growth and development are normal, and pharmacologic treatment is typically not necessary

-

Pathologic gastroesophageal reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) - Patients frequently experience the complications noted above, requiring careful evaluation and treatment [4]

-

Secondary gastroesophageal reflux - This refers to a case in which an underlying condition may predispose to gastroesophageal reflux; examples include asthma (a condition which may also be, in part, caused by or exacerbated by reflux) and gastric outlet obstruction

Patient education

Useful patient information and provider-focused information can be accessed by visiting the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) Web site.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Risk factors

Reflux after meals occurs in healthy persons; however, these episodes are generally transient and are accompanied by rapid esophageal clearance of refluxed acid. Some consider the small reservoir capacity of the infant's esophagus to be a predisposing factor to vomiting. The causes and risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux in children are frequently multifactorial.

Anatomic factors that predispose to gastroesophageal reflux include the following:

-

The angle of His (made by the esophagus and the axis of the stomach) is obtuse in newborns but decreases as infants develop; this ensures a more effective barrier against gastroesophageal reflux

-

The presence of a hiatal hernia may displace the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) into the thoracic cavity, where the lower intrathoracic pressure may facilitate gastroesophageal reflux; however, the presence of a hiatal hernia by itself does not predict gastroesophageal reflux, which means that many patients who have a hiatal hernia do not have gastroesophageal reflux

-

Resistance to gastric outflow raises intragastric pressure and leads to reflux and vomiting; examples include gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, and pyloric stenosis

Other factors that predispose individuals to gastroesophageal reflux include the following:

-

Medications - Eg, diazepam, theophylline; methylxanthines exacerbate reflux secondary to decreased sphincter tone.

-

Smoking

-

Alcohol

-

Poor dietary habits - Eg, overeating, eating late at night, assuming a supine position shortly after eating

-

Food allergies

-

Certain foods - Eg, greasy, highly acidic

-

Motility disorders (postulated to potentially cause reflux) - These include antral dysmotility and delayed gastric emptying; such disorders are considered functional problems and frequently do not have an identifiable anatomic or organic cause

-

Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (tLESR) - This is currently believed to be the main mechanism of gastroesophageal reflux, accounting for 94% of reflux episodes in children and adults; poor basal LES tone was previously thought to be a cause

-

Supine position

-

Decreased gastric emptying and reduced acid clearance from the esophagus - These can cause abnormal reflux

-

Neurodevelopmental disabilities - Children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and other heritable syndromes associated with developmental delay, have an increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux

Chronic LES laxity

Reflux is facilitated when an increase in intraabdominal pressure occurs. In some cases, and particularly in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, the presence of a chronically lax LES associated with decreased or even absent sphincter tone results in severe gastroesophageal reflux.

Transient lower esophageal relaxations

For many years, gastroesophageal reflux during infancy and childhood was thought to be a consequence of absent or diminished LES tone. However, studies have shown that baseline LES pressures are normal in pediatric patients, even in preterm infants.

The major mechanism in infants and children has now been demonstrated to involve increases in tLESRs. Factors that may promote gastroesophageal reflux during tLESRs include increased intragastric liquid volume and supine and "slumped" seated positioning.

Fluid diet

Likely because of reduced viscosity and increased gastric volumes, the fluid diet of the infant facilitates the process of regurgitation compared with solid meals ingested by older children and adults.

Esophageal clearance

Esophageal clearance is similar in infants and adults, although evidence of reduced peristaltic activity in preterm infants has been reported.

Differences between adults and infants

The volume ratio of meal-stomach-esophagus differs between adults and infants. Necessary amounts of infant caloric requirements easily overwhelm gastric capacity. Reflux occurs when esophageal capacity is exceeded by refluxate.

Decreased gastric compliance is believed to lead to LES relaxation at lower intragastric volumes in infants. This aspect, in conjunction with abdominal wall muscle contraction (if it occurs during periods of LES relaxation) propels refluxate into the esophagus, with subsequent regurgitation.

An association between gastroesophageal reflux and delayed gastric emptying is recognized. This is more common in premature infants.

Respiratory symptoms

Gastroesophageal reflux has been associated with significant respiratory symptoms in infants and children. The infant's proximal airway and esophagus are lined with receptors that are activated by water, acid, or distention. Activation of these receptors can increase airway resistance, leading to the development of reactive airway disease. [5]

In 1892, Osler first postulated a relationship between asthma and gastroesophageal reflux, manifested by a bidirectional cause-and-effect presentation. Accordingly, although gastroesophageal reflux may be involved in the etiology and progression of reactive airway disease, the asthmatic condition (in addition to antiasthmatic medications) may play a role in exacerbation of gastroesophageal reflux.

One postulated mechanism for gastroesophageal reflux–mediated airway disease involves microaspiration of gastric contents that leads to inflammation and bronchospasm. However, experimental evidence also supports the involvement of esophageal acid–induced reflex bronchospasm, in the absence of frank aspiration. In such cases, gastroesophageal reflux therapy using either histamine 2 (H2) blockers or proton pump inhibitors has been shown to benefit patients with steroid-dependent asthma, nocturnal cough, and reflux symptoms. Data from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials do not support the use of proton pump inhibitors to decrease infant crying and irritability. [6, 7]

A study by Lang et al suggested that misattribution of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms to asthma may be a contributing mechanism to excess asthma symptoms in obese children. The study reported that obese children had seven times higher odds of reporting multiple GERD symptoms and that asthma symptoms were closely associated with gastroesophageal reflux symptom scores in obese patients but not in lean patients. [8]

Other associated conditions

Two major areas of controversy surround the relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and both apnea and otolaryngologic disease. Early studies appeared to demonstrate a link between gastroesophageal reflux and obstructive apnea (including an association with apparent life-threatening events [ALTEs]); however, recent investigations now suggest only a weak relationship between these disorders. [9] Although the relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and ALTEs is controversial, where an association with apnea has been found, it is as likely to occur with nonacid as with acid reflux. Accordingly, a comprehensive evaluation of this phenomenon will likely require a bioelectrical impedance study (to identify nonacid reflux; see below) in conjunction with respiratory monitoring.

Laryngeal tissues are exquisitely sensitive to the noxious effect of acid, and studies support a significant relationship between laryngeal inflammatory disease (manifested by hoarseness, stridor, or both) and gastroesophageal reflux.

Conversely, no conclusive clinical evidence supports a link between gastroesophageal reflux and other supraesophageal problems, including otalgia, recurrent otitis media, and chronic sinusitis.

Epidemiology

Gastroesophageal reflux is most commonly seen in infancy, with a peak at age 1-4 months. However, it can be seen in children of all ages, even healthy teenagers.

United States statistics

Approximately 85% of infants vomit during the first week of life, and 60-70% manifest clinical gastroesophageal reflux at age 3-4 months.

Symptoms abate without treatment in 60% of infants by age 6 months, when these infants begin to assume an upright position and eat solid foods. Resolution of symptoms occurs in approximately 90% of infants by age 8-10 months. The estimated prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux among children aged older than 1 year and adolescents ranges from 0.9-18.8%. [10]

Prognosis

During infancy, the prognosis for gastroesophageal reflux resolution is excellent (although developmental disabilities represent an important diagnostic exception); most patients respond to conservative, nonpharmacologic treatment.

Indeed, most cases of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and very young children are benign, and 80% resolve by age 18 months (55% resolve by age 10 mo), although some patients require a “step-up” to acid-reducing medications. Symptoms that persist after age 18 months suggest a higher likelihood of chronic gastroesophageal reflux; in such cases, the long-term risks of the condition are increased. [11]

In refractory cases of gastroesophageal reflux or when complications related to reflux disease are identified (eg, stricture, aspiration, airway disease, Barrett esophagus), surgical treatment (fundoplication) is typically necessary. The prognosis with surgery is considered excellent. The surgical morbidity and mortality is higher in patients who have complex medical problems in addition to gastroesophageal reflux.

As previously mentioned, children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and other heritable syndromes associated with developmental delay, have an increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux. When these disorders are associated with motor abnormalities (particularly spastic quadriplegia), medical gastroesophageal reflux management is often particularly difficult, and suck and/or swallow dysfunction is often present. Infants with neurologic dysfunction who manifest swallowing problems at age 4-6 months may have a very high likelihood of developing a long-term feeding disorder.

Despite the immense volume of data examining diagnosis, management and prognosis related to pediatric gastroesophageal reflux, a recent review of 46 articles (out of more than 2400 publications identified) demonstrated wide variations and inconsistencies in definitions, management approaches and in outcome measures. [12]

Strictures

Gastroesophageal reflux strictures typically occur in the mid-esophagus to distal esophagus. Patients present with dysphagia to solid meals and vomiting of nondigested foods. As a rule, the presence of any esophageal stricture is an indication that the patient needs surgical consultation and treatment (usually surgical fundoplication). When patients present with dysphagia, barium esophagraphy is indicated to evaluate for possible stricture formation. In these cases, especially when associated with food impaction, eosinophilic esophagitis must be ruled out prior to attempting any mechanical dilatation of the narrowed esophageal region.

Barrett esophagus

Barrett esophagus, a complication of GERD, greatly increases the patient’s risk of adenocarcinoma. As with esophageal stricture, the presence of Barrett esophagus indicates the need for surgical consultation and treatment (usually surgical fundoplication).

-

The image is a representation of concomitant intraesophageal pH and esophageal electrical impedance measurements. The vertical solid arrow indicates commencement of a nonacid gastroesophageal reflux episode (diagonal arrow). The vertical dashed arrow indicates the onset of a normal swallow.

-

Algorithm for evaluation and "step-up" management of gastroesophageal reflux (GER).

-

Illustration of the Nissen fundoplication. Note how the stomach is wrapped around the esophagus (360-degree wrap).