Practice Essentials

A parasitic zoonosis, trichinosis (or trichinellosis) is caused by human ingestion of raw or undercooked meat infected with viable larvae of parasitic roundworms in the genus, Trichinella. Genus Trichinella is a member of the phylum Nematoda within the kingdom Animalia. Within the Trichinella genus, 8 species are known. The species are further differentiated based on whether or not the worms encapsulate in the host’s muscle tissue. See the image below.

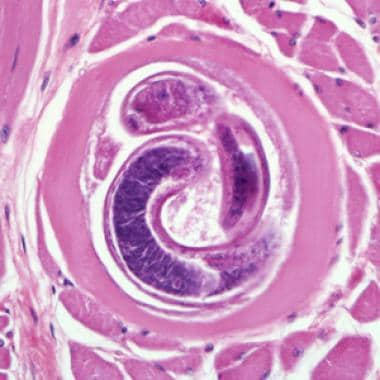

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).

Species that characteristically encapsulate are T spiralis, T nelsoni, T nativa, T murrelli and T britovi. Three species, T papuae, T pseudospiralis, and T zimbabwensis, do not encapsulate . Non-encapsulated species infect saurians and crocodilians. T pseudospiralis infects birds, T spiralis, T nelsoni, T nativa, T murrelli, and T britovi infect mammalian hosts and encapsulate within the host’s tissues. These five species of parasitic roundworms are found in approximately 150 different carnivorous/omnivorous mammals. Throughout the world, pigs (swine) are the most common meat reservoir consumed by man. Humans are incidental hosts. [1]

Background

In 1835, James Paget, a first-year medical student at Bartholomew's Hospital in London, observed the postmortem examination of a middle-aged man. The autopsy revealed extensive pulmonary tuberculosis. Paget also saw numerous miniscule chalky-colored spots in the corpse's muscles. He further verified the bony texture of these lesions and upon microscopic dissection, concluded that each lesion consisted of a coiled threadlike worm surrounded by a tiny calcified cyst. Paget’s professor, Richard Owen, confirmed his findings. Owen named it the genus Trichina, from the Greek term for hair, and the species spiralis. [2]

Pathophysiology

For T spiralis, larvae enter the human host when raw or undercooked meat is eaten with viable encysted larvae. In the stomach, larvae ex-cyst through acid-pepsin digestion. Peristalsis moves the larvae to the upper two-thirds of the intestine. There, they penetrate the columnar epithelium of the intestinal mucosa and occupy the cytoplasm of enterocytes. The intracellular larvae develop into mature worms through 4 molts, reaching adulthood in about 30 hours. [2, 3]

Adult T spiralis male worms are less than 2 mm in length (approximately 1-1.5 mm long); adult female worms are longer, measuring closer to 5 mm. Maturation of the male and female worms occurs and mating follows. Five days post-copulation, each female worm can birth a huge number of live larvae (about 1000 larvae). The newborn larvae penetrate the gut lamina propria; move through the thoracic duct and into the venous circulation. They continue to move through the right side of the heart, the lungs, and then onto the left side of the heart and subsequently enter the systemic circulation. The larvae travel throughout the human body capable of entering any tissue cell. Presence of larvae in the circulation causes increased capillary permeability and vasculitis. Fine intravascular thrombi can occur. When the larval load is significant, these microvasculature changes cause cardiovascular, lung, and central nervous system (CNS) pathology. Host cells invaded by larvae will die with the exception of skeletalmyofibrils. [3]

Larvae favor striated skeletal muscle cells and prefer active muscle groups such as the diaphragm, the tongue, and the masticatory, intercostal, and pectoral muscles. Larvae burrow into individual muscle fibers, which are transformed and serve as nurturing nurse cells. These nurse cell–larva complexes further larval development until encystment occurs; a process taking about 3 weeks. After this period, the larvae, now about 1 mm long, are infective to another host, if eaten as improperly cooked meat. In humans, the larvae at this stage have reached a dead end. Larvae may remain viable for years in the human host, but usually die and calcify within the first year after cyst formation.

A fertile T spiralis female produces approximately 500-1500 larvae over a 2-4 week period; the female is then, expelled in the feces due to the response of the host’s immune system. The host’s T-cell immune response is especially important in eradication of the adult female worms as studies of athymic mice (lacking T-cell function) show a longer intestinal phase in these mammals. [2]

In nature, the parasite's life cycle is maintained by carnivorous and omnivorous mammals that eat infected meat and by non-carnivorous animals that ingest food containing larvae-contaminated tissue from carcasses of infected animals.

Etiology

Most human infections are due to T spiralis, the Trichinella species that commonly infects pigs, wild boars, and rats. [4] T murrelli is found in black bears, raccoons, red foxes, cougars and bobcats and is the predominant species infecting wild mammals of temperate North America. [5] T britovi is found in carnivores of Europe and western Asia (eg, wild boars, horses, foxes). T nativa infects arctic and subarctic mammals such as bears, wolves, seals, and walrus; T nelsoni is common in African predators and scavengers (eg, hyenas, lions, panthers). All of these species encyst.

T pseudospiralis, T papuae, and T zimbabwensis are species that do not encyst. T pseudospiralis infects birds and marsupials. T papuae and T zimbabwensis infect saurians, crocodilians, and nonavian archosaurs. T papuae has been linked to consumption of raw soft-shelled turtles [6] and in trichinosis epidemics in Thailand. [7, 8]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Trichinosis (also known as trichinellosis ) is a reportable disease to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Parasitic Diseases Hotline (parasites@cdc.gov). The clinical case definition for trichinosis is " Trichinella –positive muscle biopsy or a positive serologic test for trichinosis in a patient with one or more clinical symptoms compatible with trichinosis such as eosinophilia, fever, myalgia, or periorbital edema."

In the 1940s, an average of 400 cases and 10-15 deaths were reported each year. The incidence of trichinosis has significantly decreased since this time. From 1991-1996, 230 cases and 3 deaths were reported. [9] From 2002-2007, 66 cases were reported. [10] In approximately 60% of these cases, information on the suspected ingested food product was available. The frequency of implicated meat was 60% pork, 23% bear meat, 10% walrus meat, and 7% cougar meat. Sausage was the most commonly cited pork product. Sampling uncooked spiced pork used to make sausage is a common way to acquire infection.

Federal regulations and changes in management standards of the pork industry have played major roles in the decreased frequency of trichinosis. Today the vast majority of domestic swine in the United States are grain-fed and uninfected. Swine fed meat from uncooked garbage containing remnants of small mammals such as skunks, raccoons and rats, are at risk to be infected if the feed contains Trichinella larvae-contaminated sources. Infections do occur sporadically in people who ingest undercooked bear meat. [5, 11]

International statistics

Trichinosis usually occurs as point-source outbreaks in all areas of the world, except Australia and some South Pacific islands. [12, 13] Incidence is low in Europe due to mandatory inspection of pork for Trichinella species, although outbreaks have been reported. [14, 15] In Arctic regions, T nativa is found in meat from walrus, seal, and polar bear. [2, 16] In Africa and southern Europe, most infections stem from T nelsoni found in meat from wild canids and felids. [2] In Turkey, T britovi, most likely from wild boar, was detected in meatballs and in human biopsies after a large outbreak occurred. [17] In Southeast Asia, most cases of trichinosis have been reported in northern Laos and Thailand among rural populations. [18]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

This infection has no racial predilection.

Both sexes are equally susceptible. Differential rates of infection between sexes may reflect differences in behavior as related to food preparation and food choices.

People of all age groups are susceptible.

Prognosis

Trichinosis is usually a self-limited illness, but death sometimes occurs if the number of infective larvae ingested is large.

Early treatment helps prevent complications during the acute stage.

Despite adequate treatment in the acute stage, infection may have long-lasting sequelae (eg, muscle aches, headaches, eye disturbances), especially in severe cases.

Morbidity/mortality

Potential clinical course and illness severity depend on the initial tissue load of viable larvae ingested and the number of newborn larvae produced per mature female.

-

Most infections are asymptomatic or subclinical.

-

One week post-ingestion, abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhea may occur

When these symptoms occur, the illness is usually self-limited.

-

Two to 8 weeks post-ingestion, symptoms can include fever, myalgias, and periorbital edema, urticarial rash, conjunctival hemorrhages and subungual hemorrhages.

During this time, the larvae are migrating into the host’s tissues.

-

In patients with severe acute infection, there may be long-lasting sequelae (eg, muscle aches and pain, headaches, eye disturbances, cardiac symptoms).

Complications

Clinical disease due to Trichinella species is classified based on the severity and likelihood of complications. The following classification also helps in patient management and prognosis:

-

Asymptomatic infection - A history of exposure associated with eosinophilia but without signs and symptoms

-

Abortive disease - Signs and symptoms that appear individually and not as a syndrome

-

Benign disease - Full syndrome of low-intensity signs and symptoms and no complications

-

Moderately severe disease - Full syndrome of significant intensity, rarely with complications

-

Severe disease - Full syndrome of highly pronounced systemic signs and symptoms with metabolic disturbances (eg, hypoalbuminemia) and circulatory or neurologic complications

Complications occur in the early or acute stages of severe or, occasionally, in moderately severe trichinosis and can usually be prevented if patients receive adequate medical and pharmaceutical treatment during early stages of the disease.

-

Cardiac: Although T spiralis larvae do not become encapsulated in heart muscle tissue, focal cellular infiltrates consisting mainly of eosinophils and mononuclear cells are observed due to their transitory stay in the heart. Cardiac muscle changes are more extensive 4-8 weeks after ingestion. Arrhythmias and heart failure may occur in exceptionally heavy infection. A prospective study showed cardiac involvement in 13% of patients, almost all of which consisted of nonspecific ST-T changes and minimal pericardial effusions without impairment of systolic function. Nkoke et al reported a case of T spiralis pericarditis, which was complicated by a large pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. [19]

-

Pulmonary: Patients with lung involvement can present with pneumonitis or bronchitis. Pan et al reported two cases in which patients with T spiralis infection presented with pleural effusion. [20]

-

Central neurologic: In cases of very severe infection, migrating larvae may penetrate cerebral tissues from blood vessels. Patients may present with obtundation or excessive excitement. Some present with signs of meningitis. [21]

-

Encysted larvae of Trichinella species in muscle tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The image was captured at 400X magnification. Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinellosis.htm).