Practice Essentials

Children with constitutional growth delay (CGD), the most common cause of short stature and pubertal delay, [1] typically have retarded linear growth within the first 3 years of life. In this variant of normal growth, linear growth velocity and weight gain slows beginning as young as age 3-6 months, resulting in downward crossing of growth percentiles, which often continues until age 2-3 years. At that time, growth resumes at a normal rate, and these children grow either along the lower growth percentiles or beneath the curve but parallel to it for the remainder of the prepubertal years. [2]

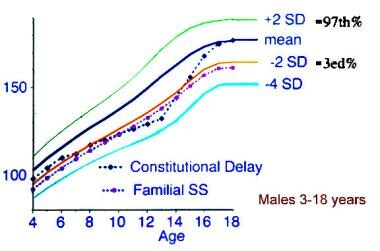

See the image below.

At the expected time of puberty, the height of children with constitutional growth delay begins to drift further from the growth curve because of delay in the onset of the pubertal growth spurt. Catch-up growth, onset of puberty, and pubertal growth spurt occur later than average, resulting in normal adult stature and sexual development.

However, a report by Rohani et al on males with constitutional growth delay—mean age 15.2 years at presentation and 20 years at study’s end—found that the majority of patients attained neither their target height nor their predicted adult height. The mean final or near-final height reached by the subjects was 165.7 cm, compared with a predicted adult height of 170.7 cm and a target height of 171.8 cm. [3]

Although constitutional growth delay is a variant of normal growth rather than a disorder, delays in growth and sexual development may contribute to psychological difficulties, warranting treatment for some individuals. Studies have suggested that referral bias is largely responsible for the impression that normal short stature per se is a cause of psychosocial problems; nonreferred children with short stature do not differ from those with more normal stature in school performance or socialization.

Signs of constitutional growth delay

Physical examination findings in patients with constitutional growth delay are essentially normal, with the exception of immature appearance for age. Body proportions may reflect the delay in growth. During childhood, the upper-to-lower body ratio may be greater than normal, reflecting more infantile proportions. In adults, the ratio is often reduced (ie, < 1 in whites, < 0.9 in blacks) as a result of the longer period of leg (long bone) growth. [4]

Workup in constitutional growth delay

Constitutional growth delay in children with slow growth or delayed puberty is a diagnosis of exclusion. Evaluation excludes hormonal deficiencies, occult systemic illness, or syndromes associated with growth impairment as potential underlying causes.

A radiographic study of the left hand and wrist to assess skeletal maturation is critical in diagnosing constitutional growth delay. Typically, the bone age begins to lag behind chronologic age during early childhood and is delayed in adolescence by an average of 2-4 years.

Management

Medical care in constitutional growth delay (CGD) is aimed at obtaining several careful growth measurements at frequent intervals, often every 6 months. These measurements are used to calculate linear height velocities and establish a trajectory on the growth curve. Medical treatment of this variation of normal growth is not necessary but may be initiated in adolescents experiencing psychosocial distress (see Medication).

Pathophysiology

Constitutional growth delay is a global delay in development that affects every organ system. Delays in growth and sexual development are quantified by skeletal age, which is determined from bone age radiographic studies of the left hand and wrist. Growth and development are appropriate for an individual's biologic age (skeletal age) rather than for their chronologic age. Timing and tempo of growth and development are delayed in accordance with the biologic state of maturity. Constitutional growth delay may be inherited as an autosomal dominant, recessive, or X-linked trait. [5]

Epidemiology

US frequency

Approximately 15% of patients with short stature referred for endocrinologic evaluation have constitutional growth delay. Individuals with constitutional growth delay and familial short stature represent another 23%. The frequency of constitutional growth delay may be underestimated because individuals with milder delays and those who are not psychologically stressed may not be seen by subspecialists. In a study of 555 (out of 80,000) schoolchildren below the third percentile in height for age with growth rates below normal (< 5 cm/y), twice as many boys as girls were affected. Constitutional growth delay was found in 28% of boys and 24% of girls, and another 18% of boys and 16% of girls had familial short stature in combination with constitutional growth delay.

Race

No racial bias has been identified.

Sex

Although the epidemiologic data indicate that all variants of normal growth are twice as common in boys as in girls, referrals for short stature reflect an even more divergent sex ratio. This likely reflects greater concern about males who are shorter than their peers or who have delayed sexual development.

Age

Patterns of growth consistent with constitutional growth delay occur in infants as young as 3-6 months. However, individuals often do not seek medical attention until puberty, when lack of sexual development becomes a concern and discrepancy in height from peers is magnified by the delay in pubertal growth spurt.

-

Comparison of the growth patterns between idiopathic short stature and constitutional growth delay.