Practice Essentials

The first two recorded cases of duodenal atresia were described by Calder in 1733. The first successfully treated case was reported by Vidal in 1905; a gastrojejunostomy was performed. In 1914, Ernest performed the first successful duodenojejunostomy in an infant with duodenal atresia. Current surgical management more commonly includes duodenoduodenostomy and duodenoplasty.

Fonkalsrud et al reviewed 503 cases of congenital duodenal obstruction treated between 1957 and 1967. [1] Of patients who were surgically treated, 64% survived. Deaths were attributed to associated malformations, respiratory complications, prematurity, and anastomotic complications.

Subsequent survival rates for infants born with duodenal atresia or stenosis have been in the range of 90-95%. [2, 3] Improved survival rates can be attributed to advances in respiratory care, hyperalimentation, improved pediatric anesthesia, improvements in the recognition and management of associated anomalies, and more refined surgical techniques (eg, the diamond-shaped anastomosis [4] ).

In 38-55% of patients, intrinsic duodenal obstruction is associated with another significant congenital anomaly. (See Presentation.) Approximately 30% of cases are associated with Down syndrome (trisomy 21), and 23-34% of cases are associated with isolated cardiac defects. Esophageal atresia may be present in 7-12% of patients. Other gastrointestinal (GI) anomalies may be seen. Duodenal atresia is associated with prematurity and low birth weight. Rarely, duodenal atresia is seen as a part of Feingold syndrome.

The definitive management of patients with intrinsic duodenal obstruction is surgical correction. [5] (See Treatment.) In a patient with associated tracheoesophageal fistula, ligation of the fistula should precede correction of the duodenal atresia. Duodenal webs can be diagnosed and excised by an expert surgical endoscopist. The morbidity and complications associated with a megaduodenum may require further surgical intervention.

Anatomy

Duodenal atresia or stenosis usually occurs in the first or second part of the duodenum, most often near the papilla of Vater. The common bile duct (CBD) may open into an intraluminal mucosal web.

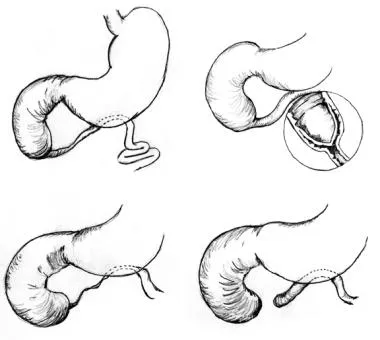

The three anatomic types of duodenal atresia, as described by Gray and Skandalakis, are as follows (see the image below):

-

Type 1 (most common type) - A membrane composed of mucosa and submucosa traverses the internal diameter of the duodenum; the duodenum and stomach proximal to the obstruction are dilated and hypertrophied, and the duodenum distal to the obstruction is narrowed; a variation of this occurs when the membrane is elongated in the shape of a windsock, and the site of origin of the membrane is proximal to the level of obstruction

-

Type 2 - The atretic ends of the duodenum are connected by a fibrous cord.

-

Type 3 - Complete separation of the atretic segments occurs; most of the biliary duct anomalies associated with duodenal atresia are observed in type 3 defects [6]

Three anatomic types of duodenal atresia are recognized. In type 1 atresia, a membrane traverses the internal diameter of the duodenum. This membrane may be elongated, giving rise to the windsock type 1 duodenal atresia. In type 2 atresia, the atretic ends of the duodenum are connected by a fibrous cord. In type 3 atresia, the atretic segments are completely separated.

Three anatomic types of duodenal atresia are recognized. In type 1 atresia, a membrane traverses the internal diameter of the duodenum. This membrane may be elongated, giving rise to the windsock type 1 duodenal atresia. In type 2 atresia, the atretic ends of the duodenum are connected by a fibrous cord. In type 3 atresia, the atretic segments are completely separated.

Various biliary tract and pancreatic anomalies have been demonstrated in patients with duodenal atresia or stenosis. These include stenosis and duplication of the distal CBD, choledochal cysts, and anular pancreas. Air in the distal duodenum and gallbladder on plain radiography is suggestive of a bifid CBD. Double duodenal atresia or stenosis is less frequently reported. [7]

Pathophysiology

In 1900, Tandler described the traditionally accepted theory on the normal development of the duodenum. [8] The duodenum develops from the caudal part of the foregut and the cranial part of the midgut. At 4 weeks' gestation, it consists of an epithelial tube surrounded by mesenchyme. At 5-6 weeks' gestation, the epithelium proliferates while the surrounding mesenchymal walls are still narrow; the epithelial cells fill the lumen, completely obliterating it.

Subsequent epithelial apoptosis at 8-10 weeks' gestation leads to vacuolation and recanalization of the duodenum. Failure of vacuolation may lead to intrinsic duodenal obstruction.

Etiology

Most cases of duodenal atresia are sporadic. Investigations of familial cases of duodenal atresia suggest an autosomal recessive inheritance in these individuals. [1, 9]

Epidemiology

The incidence of duodenal atresia is 1 case per 5000-10,000 live births.

Prognosis

Survival rates for infants with duodenal atresia or stenosis range from 90% to 95%. Higher mortality figures are associated with prematurity and multiple congenital abnormalities.

Postoperative complications are reported in 14-18% of patients; some necessitate reoperation. [2] Possible indications for reoperation include anastomotic leak, functional duodenal obstruction, adhesions, and missed atresias.

Long-term follow-up of these patients reveals that most of these patients are asymptomatic with a normal nutritional status. In a 1988 study, Kokkonen et al found a poor correlation between symptoms and radiologic and endoscopic findings; the megaduodenum failed to return to normal caliber, and duodenogastric reflux and duodenal dysmotility persisted decades after the initial surgery in asymptomatic patients. [10]

Approximately 12% of patients develop late complications. Late deaths occur in approximately 6% of patients, and 50% of these are related to complex cardiac conditions. Fewer than 10% of patients require fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux, and fewer than 10% require revision of the initial repair. [11]

Dysmotility disorders associated with megaduodenum can be managed with an antimesenteric tapering duodenoplasty or duodenal plication.

A study of 38 patients (39% male; median age, 6.7 y; range, 2.7-17.3y) who received surgical treatment for duodenal atresia in the neonatal period, including seven participants with trisomy 21, found no differences in quality-of-life (QoL) measures between all participants and published control cohorts. [12] The surgically treated children who also had trisomy 21 were more likely to have a reduced overall QoL but did not show an associated difference in gastrointestinal QoL score.

-

Three anatomic types of duodenal atresia are recognized. In type 1 atresia, a membrane traverses the internal diameter of the duodenum. This membrane may be elongated, giving rise to the windsock type 1 duodenal atresia. In type 2 atresia, the atretic ends of the duodenum are connected by a fibrous cord. In type 3 atresia, the atretic segments are completely separated.

-

This is a radiograph of a 1-day-old infant presenting with duodenal atresia. Note the distended stomach and first part of the duodenum and the absence of air distal to the duodenal bubble.

-

During the diamond-shaped anastomosis, a proximal transverse to distal longitudinal anastomosis is performed; the midpoint of the proximal incision is approximated to the end of the distal incision.