Background

Breast disorders occurring in pediatric patients range from congenital conditions to neonatal infections and from benign disorders such as fibroadenoma in females and gynecomastia in males to breast carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. [1, 2] (See the image below.)

The most common breast abnormality seen in a primary caregiver’s office in children younger than 12 years is a unilateral breast mass corresponding to asymmetrical breast development. [3] One breast commonly develops earlier than the other, though the breasts ultimately become symmetrical.

For patient education information, see Breast Lumps and Pain and Breast Self-Exam.

Embryology and Breast Development

Embryology

During the sixth week of development, the mammary glands first develop as solid downgrowths of the epidermis that extend into the mesenchyme from the axilla to the inguinal regions. Later, these ridges (ie, milk lines) disappear, except in the pectoral area. The nipple forms during the perinatal period with the proliferation of the mesenchyme underlying the areola.

At birth, the nipples are poorly formed and are often depressed. Soon after birth, the nipples are raised from the shallow mammary pits by proliferation of the surrounding connective tissue.

Breast development

Budding of the breasts, or thelarche, usually occurs at approximately age 10-11 years in females. This developmental change, along with adrenarche (ie, appearance of dark hair over the mons veneris), signifies entry into Tanner stage II of development. From this stage, complete maturation to Tanner stage V usually takes more than 4 years. Breast maturation can take place over a period as short as 18 months or as long as 9 years.

Congenital Breast Anomalies

Athelia (ie, absence of nipples) and amastia (ie, absence of breast tissue) may occur bilaterally or unilaterally. These are rare conditions and results when the mammary ridges fail to develop or completely disappear. Athelia or amastia is sometimes associated with Poland syndrome (ie, absent chest wall muscles, absence of ribs 2-5, deformities of the hands or vertebrae). Amastia in girls can be treated with augmentation mammoplasty.

An extra breast (ie, polymastia) or extra nipple (ie, polythelia) occurs in approximately 1% of the population. It may be an inheritable condition. [4] Supernumerary nipples are slightly more common in males than in females. Extra breasts or nipples most commonly occur along the milk line, usually just underneath the normally located breasts or nipples; however, they have also been noted in ectopic sites such as the back, the vulvar area, and the buttock.

Accessory or ectopic breast tissue responds to hormonal stimulation and may cause discomfort during menstrual cycles. These accessory tissues have been reported to undergo malignant transformation and should be removed. [5]

Breast Disorders in Prepubertal Children

Neonatal disorders

Influx of maternal hormones through the placenta into the fetal circulation often causes the newborn's breasts to be enlarged. In addition, some secretion (ie, witch's milk) may be evident. These changes disappear with time.

Mastitis neonatorum or infections of the breast tissue may also occur during the newborn period. Treatment includes antibiotics. If an abscess occurs, needle aspiration should be performed. Surgical drainage should be considered only when needle aspiration is unsuccessful, because an operation may damage the breast bud and result in reduction of adult breast size.

Abscess

Prepubertal girls may develop breast abscesses. The abscess manifests as a tender and erythematous mass. The most common organism causing breast abscesses in this population is Staphylococcus aureus. An increased number of skin and soft-tissue abscesses caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) have occurred in children.

Treatment involves antibiotics, needle aspiration, or surgical drainage. The decision for surgical drainage should be carefully made because future breast deformation may occur. For this reason, needle aspiration is the preferred treatment. [6] The literature suggests that drainage alone, without adjunctive antibiotics, may be effective in skin and soft-tissue abscesses caused by MRSA; no definitive antibiotic recommendation regarding MRSA breast abscesses in particular is recognized. [7]

Benign premature thelarche

Benign premature thelarche is defined as isolated breast development in females aged 6 months to 9 years. Physical examination for this entity should carefully seek out other signs of puberty, such as development of pubic hair, thickening of the vaginal mucosa, and accelerated bone growth. If no other signs of puberty are present, reassure the patient and family that this is a benign finding. Examine the child every 6-12 months. If other signs of puberty are evident, precocious puberty should be entertained as a diagnosis.

Precocious puberty

Early onset of puberty is more common in girls than in boys and is predominantly mediated by premature activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Central precocious puberty may be caused by hypothalamic hamartomas, trauma, or central nervous system (CNS) lesions; however, it is most commonly idiopathic. Treatment involves continuous administration of exogenous gonadotropins.

Peripheral precocious puberty is due to sex steroid secretion independent of gonadotropin release; causes include McCune-Albright syndrome.

When precocious puberty is suspected, tests for luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), testosterone, and estradiol should be performed.

Breast Disorders in Adolescent Girls

Asymmetry

Breast asymmetry may develop as thelarche ensues. In this condition, one breast may develop before or more rapidly than the other. The physical examination findings usually include homogenous enlargement of one breast with no discrete masses or discharge. Accompanying breast tenderness may be present if the breast bud is starting to develop. If a mass is excluded, either by physical examination or by ultrasonography (US), the patient and parents can be reassured that the asymmetry will become less noticeable with age.

Piercing-associated infection

Body piercings in general have become more common, and some studies have reported nipple piercings that caused local infection and disfiguration. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species are the common causative organisms, but three cases have reported Mycobacterium infection. [8] Treatment includes appropriate antibiotics and removal of the foreign body. [9]

Abscess

Breast abscesses may occur in adolescent women, particularly if they are lactating. These are managed with antibiotics, drainage using US or drainage in the operating room, or both. Good success has been reported for US-guided abscess drainage. [10, 11] The reported healing time for US-guided needle aspiration is significally less than that for open incision and drainage; thus, it may be the preferred treatment. [6] Mastitis in nonlactating adolescents may occur. [12] S aureus is the usual cause in cases that require drainage; however, most patients respond to oral antibiotics without additional intervention.

Fibroadenoma

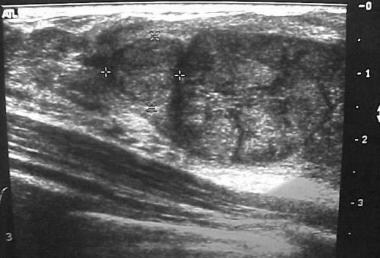

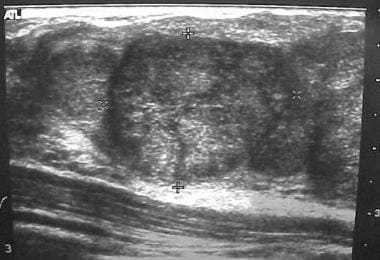

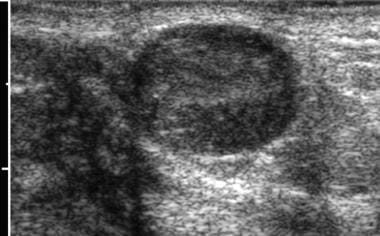

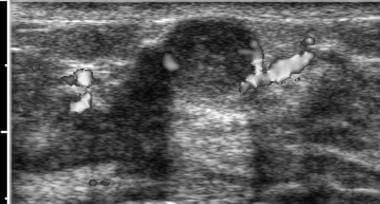

Breast masses in adolescent girls are usually benign. The most common discrete breast mass is a fibroadenoma (70%). Upon examination, these masses are smooth, mobile, and round (see the images below). They may occasionally become larger just before the patient's menstrual period.

Ultrasonogram of fibroadenoma with color Doppler. Note lack of vascularity of the lesion. Image courtesy of Brian Coley, MD.

Ultrasonogram of fibroadenoma with color Doppler. Note lack of vascularity of the lesion. Image courtesy of Brian Coley, MD.

Masses with the characteristics of fibroadenoma may be serially monitored (every 1-3 mo) with a careful physical examination. Alternatively, an excisional biopsy may be performed if the patient and family request it. As many as 15% of patients may have multiple fibroadenomas. Studies suggest that fibroadenomas may be treated with US-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA). [13] Complete ablation of the fibroadenoma, as confirmed by follow-up US, occurred in 98% of patients.

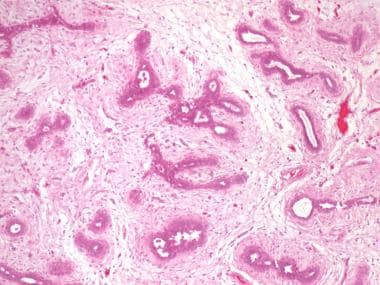

Juvenile, or giant, fibroadenomas are unusually large (>5 cm). They usually display rapid growth but are in most cases benign. Management consists of surgery. Histologically, juvenile fibroadenomas have more cellularity than typical fibroadenomas (see the image below). They should be differentiated from phyllodes tumor (cystosarcoma phyllodes).

Phyllodes tumor (cystosarcoma phyllodes)

Phyllodes tumor manifests as a painless breast mass. [14] Patients may have a history of sudden enlargement of a previously stable mass. The mass may be dramatically large; thinning of overlying skin and increased vascularity of the area may be present. This tumor is very rare, accounting for only 0.5% of all breast tumors. [15]

Generally, US cannot be used to distinguish between a fibroadenoma and a phyllodes tumor. The differentiation between a fibroadenoma and a phyllodes tumor lies in histologic examination. Phyllodes tumors are fibroepithelial lesions with more cellular stroma with nuclear atypia and mitotic figures. As many as 25% of phyllodes tumors are considered malignant, but histologic classification does not reliably predict behavior. [15]

The management of a benign or malignant phyllodes tumor involves wide excision with a margin of normal breast tissue. Positive resection marigins, stromal overgrowth, and infiltrative tumor borders are associated with increased local recurrence. [16, 15] . Malignant phyllodes tumors rarely metastasize to the axilla. Axillary dissections are indicated for patients with palpable lymph nodes. Local recurrence and hematogenous spread, even after complete resection, may occur with as many as 22% of malignant tumors. [15]

Hamartoma

Breast hamartomas are rare in the adolescent population but have been described. [17] They may develop in patients with Cowden syndrome or may be an isolated finding in the adolescent patient.

Histologically, breast hamartomas are densely packed, enlarged lobules in a fibrous stroma. Clinically, they present as discrete painless masses similar to a fibroadenoma. The characteristics of breast hamartomas on US are similar to those of breast fibroadenomas. They are treated with complete surgical excision and can recur if not completely removed.

Trauma

Trauma to the breast, iatrogenic or blunt, may result in a palpable mass. The trauma causes fat necrosis, or breakdown of the adipose tissue. To complicate the diagnosis, women may or may not recall the inciting event. In addition, women may examine a traumatized breast and discover a mass that was present prior to the event.

On physical examination, the mass is sometimes indistinguishable from a cancer. US, mammography, and even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast may be unable to discern the difference, leading to biopsies in concerning masses. Although pathognomonic for fat necrosis, key features—including peripheral calcifications, fibrotic scar, and echogenic internal bands—may also be consistent with breast cancer. [18] Findings of lipid cysts or US evidence of fat necrosis may assist in the decision to monitor a palpable abnormality or perform a biopsy. [19]

Fibrocystic changes

Fibrocystic changes of the breast are very common in the adolescent population. [20] Physical examination findings may reveal discrete breast cysts or diffuse, small lumps throughout. Breast tenderness and heaviness may be experienced by the patient, especially before her menstrual period. The patient is advised to avoid caffeine. Evening primrose oil (1 tbsp at bedtime) may be used to alleviate breast pain associated with fibrocystic changes of the breast. [21]

A single dominant lump that is present for several months likely requires excisional biopsy. Single dominant cysts may be aspirated in an outpatient setting. Cytopathologic examination should be conducted if the fluid is bloody. Fibrocystic changes are histologically classified into the following three categories:

-

Nonproliferative changes

-

Proliferative changes without atypia

-

Proliferative changes with atypia

Patients with proliferative changes, atypia, or both have a higher risk for future malignancies.

Although no specific data are available in adolescents, the risks in adults are well described. Proliferative fibrocystic disease (described histologically as moderate or florid hyperplasia, sclerosing adenosis, or papilloma with a fibrovascular core) has been associated with a 1.5-fold to twofold increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most substantial increase in risk of breast cancer is observed in patients with atypical or lobular hyperplasia; this is associated with a 4.4-fold increase in cancer risk, which increases to ninefold with a positive family history. [22]

Screening guidelines for patients with a history of atypia on breast biopsy findings are still evolving. In adults, current recommendations include yearly physician examinations and yearly mammography. [23] Patients should be aware of the limitations and should be taught how to perform self-examinations on their breasts. No data indicate that the additive radiation from mammography increases the risk of breast cancer. These recommendations should be followed in children and adolescents.

Mammary duct ectasia

Mammary duct ectasia is a benign lesion of the breast that consists of dilation of the mammary ducts, periductal fibrosis, and inflammation. This entity has been described in infants, prepubertal boys and girls, and adult men and women. The patient presents with nipple discharge, which may be bloody. In children and adolescents, the lesion is usually unilateral. Infectious and inflammatory causes have been implicated in the etiology of mammary duct ectasia.

Findings on US are usually suggestive, revealing dilated mammary ducts radially located around the nipple. The process is usually self-limited; therefore, surgery is not recommended if the diagnosis is certain. [24, 17]

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia is a benign and usually self-limited condition that occurs in 50-60% of boys during early adolescence. Physical examination findings range from discrete, 1- to 3-cm, round, mobile, and usually tender masses located just underneath the areola to diffusely enlarged breasts. If the mass is large or fixed or if a discharge is present, further workup is necessary.

Young men with gynecomastia may often be monitored in the clinic and may be reassured that the condition is self-limited. If the breast enlargement is such that it causes pain, discomfort, or psychological trauma, subcutaneous mastectomies may be performed. Novel approaches such as liposuction or pediatric endoscopic subcutaneous mastectomy with liposuction may be of benefit for those with persistent gynecomastia or symptoms. [25] Aromatase enzyme inhibitors are being tested for use in shrinking breast tissue in adolescents with gynecomastia, but their widespread use has not been described. [26]

The differential diagnosis for gynecomastia includes the following:

-

Testicular feminization

-

Hormone-secreting tumors

-

Drug use (eg, cimetidine, marijuana)

-

Familial predisposition

Malignant Breast Disease in Children and Adolescents

Malignant breast disease is uncommon in children and in adolescents. Risk factors for breast malignancies include the following:

-

History of familial breast cancer

-

Previous benign disease associated with malignancy (ie, fibrocystic changes with atypia)

-

Other malignancies

-

Irradiation to the neck and chest areas

The most common malignant mass in the breast of a child or adolescent is a metastatic lesion.

Ashikdri et al reviewed the world literature between 1888 and 1977 and found a total of 74 cases of carcinoma of the breast in children and adolescents. [27] Initial surgical options for infiltrating lobular or intraductal carcinoma in adolescents include breast-sparing surgery (ie, lumpectomy with axillary node dissection and irradiation) and modified radical mastectomy. Younger women tend to have more aggressive disease.

Systemic adjuvant chemotherapy is strongly advised in all young women with breast carcinoma. No concrete recommendations regarding the use of endocrine methods (ie, ovarian ablation) in the treatment of breast cancer in these women are available. [28] Other primary malignancies of the breast include rhabdomyosarcoma and Hodgkin disease. [29] Metastatic disease in children is more often rhabdomyosarcoma. [30]

The average American female has an 11% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. The risk in a first-degree relative (ie, mother, sister, daughter) of a breast cancer patient is two- to threefold greater. [31, 32] This risk is increased to ninefold when the patient has bilateral premenopausal breast cancer.

Genetics

Only 5% of all breast cancer patients have true hereditary breast cancer. Families with hereditary breast cancer have the following characteristics:

-

Early onset of breast cancer - Usually before age 45 years

-

Increased incidence of bilateral breast cancer

-

Autosomal dominant inheritance for breast cancer

-

Greater frequency of multiple primary cancers

Adolescents of a parent with hereditary breast cancer have a 50% chance of inheriting the causative gene. Current recommendations suggest that mature young women consider genetic testing for the purposes of family and life planning. [33] However, because few proven early interventions are available, genetic testing may be delayed until childbearing is complete or until age 35 years or older.

Two breast cancer susceptibility genes have been mapped. BRCA1 has linkage with breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers. The BRCA1 gene confers an 83% breast cancer risk and a 63% ovarian cancer risk by age 70 years. BRCA2 has linkage with male and female breast cancers. Overall, the lifetime risk of development of breast cancer in known BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers is 60-80%. [34, 35]

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

Other groups are known to have an increased susceptibility to breast cancer. Families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome have p53 mutations, which are associated with an increased risk for sarcomas, breast cancer, lung cancer, laryngeal cancer, leukemia, and adrenal cortical carcinoma. [36] The pattern of transmission is autosomal dominant. Breast cancer develops in 77% of women with Li-Fraumeni syndrome between the ages of 22 and 45 years, with 25% developing bilateral disease. Rarely, tumors may develop in the teenaged patient.

Cowden disease

Cowden disease is characterized by multiple benign keratoses located at the mucocutaneous sites on the face, hands, feet, and forearms; goiter; lipomas; and uterine leiomyomas. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast may develop in 30% of these women; one third of these cases are bilateral. [37]

Ataxia-telangiectasia

Ataxia-telangiectasia syndrome is characterized by multiple telangiectasias, immune dysfunction, sensitivity to ionizing radiation due to chromosomal fragility, and progressive neuromuscular deterioration. Heterozygotic individuals have a fivefold greater risk of developing breast cancer.

Mutation

Mutations of genes associated with inherited forms of colon cancer (ie, MSH2, MLH1) are associated with multiple skin malignancies, gastrointestinal malignancies, and breast cancer. [38]

Screening

Screening recommendations for families with hereditary breast cancer (ie, BRCA1, BRCA2, Li-Fraumeni) include examination by a physician twice a year. Screening mammography should be performed once or twice yearly, beginning when the patient is aged 10 years younger than the youngest affected relative or no older than age 35 years.

Patients who have positive test findings for the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes may opt to undergo prophylactic bilateral mastectomy, which is associated with an approximately 90% reduction in the risk of breast cancer. [39] Depending on the age at diagnosis in the first-degree relative, prophylactic mastectomies may be delayed until age 35 years or until childbearing is complete. [33]

Ionizing radiation

Exposure to ionizing radiation has been shown to increase breast cancer risk. The patient's age during exposure is correlated with the risk; the highest risk is posed to the adolescent, whereas exposure in those older than 40 years only minimally increases the risk. Also, the latency period is long.

Women aged 25 years or older who were exposed to ionizing radiation before age 30 years (eg, mantle irradiation for Hodgkin disease, [40] thymic irradiation for enlargement, radiation for mastitis, radiation exposure from nuclear fall-out) should be examined by a physician twice a year and should undergo annual mammography and MRI, beginning 8 years after radiation exposure. [23, 41] The lag of 8 years is because of the long latency period of radiation damage to tissue.

Because mammography has limited use in evaluating dense breast tissue, only twice-yearly physician examinations are recommended in patients younger than 25 years. [42, 43]

History and Physical Examination

When a patient presents with a breast mass, ensure that the history includes the following:

-

Family history of breast and ovarian malignancies

-

Family history of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations

-

Previous history of malignancy

-

Previous chest irradiation

-

History of trauma

-

History of other breast masses

Perform a complete and thorough examination of both breasts to evaluate for masses and nipple discharge. Characterize breast masses according to the following characteristics:

-

Size

-

Contour (ie, smooth vs irregular)

-

Overlying skin changes (eg, dimpling, edema)

-

Fixation

Examine the lymphatic basins of the breast (ie, axillary, infraclavicular, supraclavicular areas) for enlarged lymph nodes.

Adolescents who carry BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations should begin routine office visits at age 20 years to undergo clinical breast examination and to receive information regarding their risk of developing breast cancer. [23] However, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has discouraged genetic testing for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations in children and adolescents because of a lack of timely medical benefit and due to psychosocial risks in this population.

Ultrasonography

Because of the density of the breast tissue in young children, mammography is not usually very helpful. [44] US is more effective at delineating masses within the immature breast. [45] Color Doppler US may increase the specificity of the diagnosis: Cysts are avascular, fibroadenomas are hypovascular, and abscesses show increased peripheral flow. [46]

Data suggest that US findings alone may guide management in most cystic and solid-cystic lesions. [47] Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) may be performed to manage breast cysts [48] ; US should be performed often to ensure that normal breast tissue is not harmed.

The Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS), which was developed in adult patients to determine the risk of cancer, is currently used in the pediatric population but may not be fully applicable to these patients. [49] A study by Koning et al demonstrated that BI-RADS grossly overestimated the risk of malignancy in the pediatric population.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI with gadolinium-based enhancement has drawn interest as a modality for studying breast disease. [50] However, findings have been inconsistent. For example, age and menstrual cycle may affect parenchymal contrast medium enhancement. [51] In women with a high risk of breast cancer, breast MRI has high sensitivity (88%) but only moderate specificity (67%). [52]

In patients aged 25 years or older, guidelines recommend annual MRI as an adjunct to mammography in women at high risk, including the following [41] :

-

Women with a BRCA mutation

-

First-degree relatives of a BRCA carrier (untested)

-

Women with a lifetime risk of 20-25%

-

Women who received radiation to the chest between ages 10 and 30 years

-

Women with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden syndrome, or Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome or first-degree relatives of individuals with those syndromes

The use of MRI in the pediatric and adolescent population has not been described.

Biopsy

In very young and preadolescent children, a biopsy should be considered with extreme caution because the developing breast bud may be irreparably harmed, even with a needle aspirate. Discrete masses should almost always be removed in boys and postpubertal girls unless the clinical and imaging features are characteristic for benign fibroadenoma, in which case observation with follow-up examination is an option. Excisional biopsies are usually performed via a circumareolar incision; if the mass is distant from the areola, an incision directly overlying the mass may be used.

As previously discussed, biopsies are sometimes performed in adolescent girls being examined for various conditions, such as fibroadenomas, trauma-related masses, and fibrocystic changes.

Questions & Answers

Overview

What are pediatric breast disorders?

What is the normal process of breast development?

Which pediatric breast disorders are congenital?

What are neonatal breast disorders and how are they treated?

What causes abscesses in pediatric breast disorders?

How are pediatric breast abscesses treated?

What is benign premature thelarche?

What causes precocious puberty?

What is asymmetry in pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of body piercing in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

How are abscesses treated in pediatric breast disorders?

How are fibroadenomas characterized in pediatric breast disorders?

How are hamartomas diagnosed and treated in pediatric breast disorders?

What are the traumatic causes of pediatric breast disorders?

Which physical findings suggest fibrocystic changes in pediatric breast disorders?

What are the histologic classifications of fibrocystic changes in pediatric breast disorders?

What is the risk of malignancy in fibrocystic pediatric breast disorders?

How is mammary duct ectasia in pediatric breast disorders diagnosed and treated?

What is gynecomastia in pediatric breast disorders?

Which conditions should be included in the differential diagnoses for gynecomastia?

What is the role of Cowden disease in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

What are risk factors for malignancies in pediatric breast disorders?

How are malignancies treated in pediatric breast disorders?

What are the risks for breast cancer in patients with pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of genetics in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of Li-Fraumeni syndrome in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of ataxia-telangiectasia syndrome in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of genetic mutation in the development of breast disorders?

What are the screening recommendations for families with hereditary breast cancer?

What is the role of ionizing radiation in the development of pediatric breast disorders?

Which clinical history findings are characteristic of pediatric breast disorders?

What is included in the physical exam of breast disorders?

What is the role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of MRI in the diagnosis of pediatric breast disorders?

What is the role of biopsy in the diagnosis of pediatric breast disorders?

-

Fibroadenoma. Ultrasonogram courtesy of Helen Pass, MD.

-

Fibroadenoma. Ultrasonogram courtesy of Helen Pass, MD.

-

Ultrasonogram of fibroadenoma with color Doppler. Note lack of vascularity of the lesion. Image courtesy of Brian Coley, MD.

-

Ultrasonogram of fibroadenoma. Image courtesy of Brian Coley, MD.

-

Hematosin and eosin (H&E) stain of fibroadenoma. Image courtesy of Beth A. Trost, MD.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Background

- Embryology and Breast Development

- Congenital Breast Anomalies

- Breast Disorders in Prepubertal Children

- Breast Disorders in Adolescent Girls

- Gynecomastia

- Malignant Breast Disease in Children and Adolescents

- History and Physical Examination

- Ultrasonography

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Biopsy

- Questions & Answers

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References