Practice Essentials

Although several variations exist, the classic definition of turf toe is a hyperdorsiflexion injury of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. [1, 2, 3] Some have suggested that the concept could usefully be broadened to encompass a variety of traumatic lesions of the first MTP joint. [4] Since approximately the 1980s, turf toe has received increased attention in the media because of its effect on college-level and professional athletes. [5, 6, 7, 8, 2, 9]

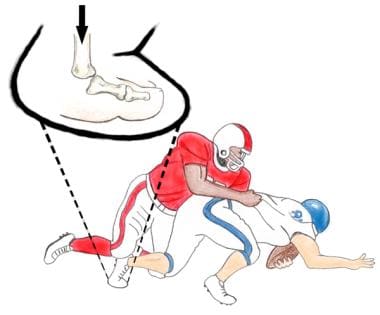

Turf toe injury is most commonly seen when an axial load is delivered to a foot that is fixed in equinus. The typical scenario, which often occurs in linemen in American football, involves the fixation of the forefoot on the ground in the dorsiflexed position with the heel raised. An outside force then pushes the foot into further dorsiflexion, resulting in traumatic hyperextension of the hallux MTP joint (see the image below). Although turf toe is most frequently seen in football players, [10] it can occur in athletes in any sport (eg, basketball, soccer, or rugby).

Typical mechanism of turf toe injury. Foot is fixed on ground in equinus position while external force drives metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint into hyperextension.

Typical mechanism of turf toe injury. Foot is fixed on ground in equinus position while external force drives metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint into hyperextension.

Although turf toe was once thought to be a low-morbidity injury, significant disability can occur with damage to the periarticular structures of the MTP joint complex. Such damage often is accompanied by long- and short-term sequelae. As many as 50% of individuals with turf toe injuries have persistent symptoms after 5 years. In the short term, running and pushing off are compromised, and players frequently miss games and practices. Possible long-term sequelae include hallux rigidus, hallux valgus, hallux cockup deformity, and failure to regain pushoff strength.

Variations to the classic turf toe injury can occur that account for damage to specific anatomic structures in the capsuloligamentous-sesamoid complex. These include hyperplantarflexion injuries ("sand toe"), as well as valgus- and varus-type injuries. Because each mechanism affects different structures, an accurate history is crucial for understanding available nonoperative and operative treatment options. [11]

Brophy et al found that in professional football players with a history of turf toe, first MTP dorsiflexion was significantly lower in halluces with a turf-toe history (40.6 ± 15.1º vs 48.4 ± 12.8º), and peak hallucal pressures were higher. [12]

Before the advent of artificial playing surfaces in the late 1960s, sprains to the hallux MTP joint were relatively uncommon. As artificial turf became popular in sports, the incidence of MTP joint injuries appeared to increase. During a roundtable discussion in 1975 regarding the benefits and drawbacks of artificial turf, Garrick first suggested the relationship between first MTP joint sprains and the use of synthetic playing surfaces. [13] One year later, Bowers and Martin introduced the term turf toe to describe a plantar capsuloligamentous sprain of the first MTP joint related to two predisposing factors: hard artificial surfaces and soft-soled shoes. [14]

The earliest synthetic surfaces contained a synthetic nylon ribbon that wore away over time. Beneath that was a foam underpad that quickly became packed down, leaving a virtual asphalt-carpet interface. As a consequence, the effect of surface hardness was originally thought to be responsible for turf toe injury.

After the development of artificial turf, many players complained of poor traction with traditional shoes designed for use on grass surfaces. Despite lower rates of injuries, the demand for increased speed and traction in sports (eg, football) led to the development of a more flexible shoe. A softer, soccer-style shoe replaced the traditional multicleated shoe containing a steel plate in the forefoot that was designed for grass surfaces. This shoe allowed a greater degree of motion in the MTP joints and placed significantly more stress across the forefoot.

In 1978, a major study from the University of Arkansas by Coker et al cited turf toe as a major cause of missed games and practices. [15] However, it was not until 1986 that Clanton et al developed a classification scheme for describing the degree of severity for turf toe injury. [16] With some minor revisions since its original publication, this system continues to be helpful in guiding treatment, as well as in predicting return to play.

No evidence-based treatment guideline is currently available for turf toe. [17] Most MTP joint injuries can be managed nonsurgically; however, when the injury is refractory to conservative treatment, surgery should be considered as an option. It should be noted that the need for surgical management is relatively uncommon.

Anatomy

To understand how turf toe injury occurs, a thorough understanding of all anatomic structures in and around the MTP joint is critical. Unlike a simple hinged joint, the hallux MTP joint functions more like a hammock or an acetabulum. It contains multiple centers of motion, including sliding, rolling, and compression.

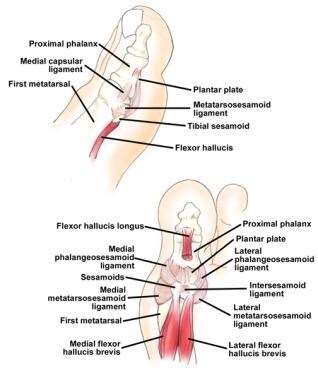

As in the glenoid cavity of the shoulder, the shallowness of the articular surface of the proximal phalanx provides little stability to the joint. The capsuloligamentous-sesamoid complex contributes most of the stability observed in the MTP joint. This complex is made up of collateral ligaments, along with the plantar plate, the flexor hallucis brevis (FHB), the adductor hallucis, and the abductor hallucis (see the image below).

The medial and lateral collateral ligaments are composed of an MTP and a metatarsosesamoid ligament. They originate on either side of the metatarsal (MT) head and fan out distally to attach to the proximal phalanx.

The plantar plate is a strong, fibrous structure that is firmly attached to the proximal phalanx and is loosely attached to the metatarsal neck through the joint capsule. It blends with the sesamoids and tendons of the FHB to provide structural support.

The sesamoid bones play a crucial role in providing stability to the MTP joint complex and in enhancing the tendon moment arm of the flexor hallucis brevis.

The FHB originates on the cuboid and lateral cuneiforms before splitting into medial and lateral heads that extend beneath the first MT bone. Tendon fibers envelop the sesamoid bones just proximal to an insertion point at the base of the proximal phalanx. The FHB plays an integral role in providing push-off strength for the hallux.

The abductor hallucis and adductor hallucis tendons contribute additional stability through their insertions on the medial and lateral plantar portions, respectively, of the capsuloligamentous complex.

Proper function of the MTP joint is essential to normal foot biomechanics. The great toe typically bears twice the load of the lesser toes, and during normal gait, it withstands 40-60% of the body weight. This load increases severalfold with running or jumping, and it may rise to nearly eight times an individual's body weight with a running jump.

The normal MTP joint is in approximately 16º of dorsiflexion relative to the longitudinal axis of the first MT, and it has a passive arc of motion in the range of 3-43º plantarflexion and 40-100º dorsiflexion. During normal gait, this angle is 60º on average, but it may decrease to 25-30º dorsiflexion in a stiff-soled shoe without affecting gait.

The lighter, softer-soled shoes now widely used in high-performance activities (eg, professional and college-level sports) allow greater MTP joint motion. The resulting increase in speed and flexibility occurs at the expense of stability, with greater stresses across the forefoot.

Pathophysiology

The normal MTP joint functions with a smooth gliding motion, except during full dorsiflexion, when some compression occurs. Tears of the joint capsule occur at the MT neck rather than at the proximal phalanx because the MT neck is its weakest point of attachment.

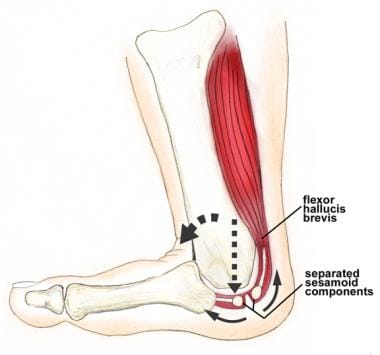

Once the capsure is torn, unrestricted motion of the proximal phalanx results in severe compression of the dorsal articular surface of the MT head. This produces the potential for fracture or possibly even for dislocation (see the video below). Usually, the plantar portion of the ligamentous complex tears, and the plantar plate becomes detached distal to the sesamoids. Rarely, fracture of the sesamoid bone may occur (see the image below).

Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint hyperextension with tearing of plantar plate complex. Unrestricted motion of proximal phalanx results in severe compression of articular surface of metatarsal head along with separation of sesamoid components.

Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint hyperextension with tearing of plantar plate complex. Unrestricted motion of proximal phalanx results in severe compression of articular surface of metatarsal head along with separation of sesamoid components.

Other mechanisms of turf toe injury include valgus and varus injuries, as well as hyperflexion-related damage. Valgus injury is a variant of the dorsiflexion-type injury in which the medial ligamentous structures and, in some cases, the medial sesamoid bone are damaged. This most often occurs in the setting of pushoff, when internal rotation occurs on a fixed forefoot. Untreated, this may lead to bunion formation and contractures on the lateral side of the joint.

More rarely still, a varus injury may result from external rotation on a fixed forefoot. Patients may present with varus instability resulting from a torn lateral capsule as well as from rupture of the adductor hallucis tendon from the base of the proximal phalanx.

Hyperflexion occurs when the MTP joint is forced into exaggerated plantarflexion. This injury has been referred to as sand toe, in that it often occurs in beach volleyball players. It has also been known to occur in football players and dancers. A plantar foot with the MTP joints driven into exaggerated hyperflexion can result in tearing of the dorsal capsule. The anatomic structures that are damaged and the injury treatment required are different from those of classic turf toe and should be recognized as such.

Etiology

Bowers and Martin coined the term turf toe to acknowledge the predisposing factor of artificial synthetic surfaces on hallux MTP joint sprains. [14] They found that injuries occurred most frequently in athletes playing on artificial turf who wore flexible, soccer-style shoes.

Data collected from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance System has been useful in identifying key susceptibility factors. Injuries seem more likely to occur in games as opposed to practices and with artificial as opposed to natural grass. Furthermore, a greater percentage of injuries appear to occur in running backs and quarterbacks. More detail regarding causative factors is located below. [18]

Footwear

Throughout the past several decades, football shoes have evolved from the traditional seven-cleat shoe containing a metal plate in the sole designed for grass surfaces to a more flexible, soccer-style shoe designed for grass surfaces and, finally, to a shoe designed for artificial turf. These changes in shoe type have allowed increased speed at the expense of stability. The absence of a stiff sole places the forefoot, and specifically the MTP joints, at much greater risk of sustaining stress-type injuries. Athletes wearing flexible turf shoes are much more prone to injury than are those wearing shoes containing a stiff forefoot.

Synthetic surfaces

Artificial grass contains a higher coefficient of friction and tends to lose some of its resiliency and shock absorbency over time. The combination of increased surface friction and a hard undersurface is believed to play a major role in the natural history of the injury. A higher coefficient of friction places the forefoot at greater risk of becoming fixed to the playing surface. Thus, the forefoot becomes more prone to an external force that places the hallux MTP joint in a position of extreme dorsiflexion.

Ankle range of motion

The risk of turf toe appears to be related to the range of motion (ROM) in the ankle of the injured person. A greater degree of ankle dorsiflexion has been correlated with the risk of hyperextension to the first MTP joint.

Miscellaneous

Other factors have been postulated to play a role in turf toe. These include a player's position, weight, and years of participation, as well as hallux interphalangeal degenerative joint disease, pes planus, and prior injury. For the most part, study results regarding these factors have been inconclusive. It is worth mentioning, however, that a number of groups, after researching the question, have found no correlation between MTP joint ROM and the associated risk of turf toe.

Epidemiology

The actual incidence of turf toe has never clearly been defined. In certain sports, such as football and rugby, a predisposition to turf toe injury is higher than it is in other sports. A retrospective 5-year analysis of NCAA football players showed an overall incidence of 0.062 per 1000. [18] This value may actually be higher in elite professional players. Division I athletes encountered nearly twice the number of turf toe injuries as compared with lower-division athletes.

Turf toe ranks as the third most common injury (after knee and ankle traumas) causing loss of playing time among university athletes. [19] Although ankle injuries are up to four times as common as turf toe, the latter may account for a significantly greater proportion of missed playing time. A study using data from the NCAA Injury Surveillance System to evaluate severe injuries (season- or career-ending injuries, injuries with >30-day time loss, or injuries requiring operative treatment) in US collegiate athletes found that turf toe was associated with the second highest rate of career-ending injury, after severe flexor/extensor injury. [20]

Prognosis

In many cases, if adequate compliance is achieved, conservatively and surgically treated patients can return to their preinjury level of function. [21, 10, 22] Studies have shown good results with operative repair in professional athletes. [23, 24] However, some disability is possible with either form of treatment.

Pinter et al assessed outcomes in 12 nonathlete patients who underwent operative repair of chronic turf toe injury. [22] On initial clinical presentation, all 12 had local tenderness with associated painful ROM; four had restricted ROM; all 12 had a positive Lachman test; two had local edema; and eight had hallux valgus deformity. With treatment, mean Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores improved from 4.6 (range, 2-9) to 1 (range, 0-4), and mean Foot Function Index (FFI) scores improved from 102.5 (range, 56-177) to 61.75 (range, 23-144). At final follow-up, all patients had a negative Lachman test. None of the patients developed major complications or required revision surgery.

At present, the incidence of persistent symptoms and late-onset sequelae requires further understanding. In the literature, the incidence of persistent symptoms has been as high as 50% after 5 years.

Although acutely based injuries to the plantar plate and surrounding structures are better defined today, less information is available regarding the management of chronic or late diagnosed injuries.

Above all, turf toe clearly represents a significant injury that deserves adequate recognition and treatment, especially in light of the complications that may occur when the condition is mismanaged.

-

Typical mechanism of turf toe injury. Foot is fixed on ground in equinus position while external force drives metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint into hyperextension.

-

Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint hyperextension with tearing of plantar plate complex. Unrestricted motion of proximal phalanx results in severe compression of articular surface of metatarsal head along with separation of sesamoid components.

-

Capsuloligamentous-sesamoid complex of hallux. Top, medial view; bottom, plantar view.

-

Typical method for obtaining stress radiograph.

-

Techniques for reconstructing passively correctable claw-toe deformity.

-

Techniques for reconstructing passively correctable claw-toe deformity.

-

Protection of hallux metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is imperative after surgical intervention. Darco Wedge shoe allows weightbearing on hindfoot and simultaneous protection of forefoot.

-

Great toe dislocation. Video courtesy of Vinod K Panchbhavi, MD, FRCS, FACS.

-

Intraoperative steps. Video courtesy of Vinod K Panchbhavi, MD, FRCS, FACS.