Background

Torticollis is the common term for various conditions of head and neck dystonia, which display specific variations in head movements (phasic components) characterized by the direction of movement (horizontal, as if to say "no", or vertical, as if to say "yes"). Such to-and-fro movements of the head can be equal (as in a tremor) or unequal (ie, rapid clonic movements of the head and neck with slow recovery, termed spasmodic). Torticollis is derived from the Latin, tortus, meaning twisted and collum, meaning neck.

Torticollis results in a fixed or dynamic posturing of the head and neck in tilt, rotation, and flexion. [1] Spasms of the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and other neck muscles, usually more prominent on one side than the other, cause turning or tipping of the head. [2, 3] Note the images below.

Characteristic head tilt often occurs from a tonic component. One example is laterocollis, in which the head is displaced with the ear moved toward the shoulder from increased tone in the ipsilateral cervical muscles. Another is rotational torticollis, in which partial rotation or torsion of the head occurs along the longitudinal axis. In anterocollis, the head and neck are held in forward flexion with increased tone of anterior cervical muscles; in retrocollis, the head and neck are held in hyperextension with increased tone in the posterior cervical muscles.

No matter which term is preferred in communicating about these conditions, the implication is that they all represent differing degrees of the same phenomenon. Jankovic et al [4] and Chan et al [5] preferred to avoid the popular term spasmodic torticollis and instead preferred cervical dystonia, because many patients have neither simple rotation nor spasmodic movements. In fact, several patients have combinations of movements, not as simple tremors but as responses to dystonic motor control.

Torticollis is not a diagnosis but a symptom of diverse conditions. Presentations of torticollis or cervical dystonia are often defined using causal terms—acute torticollis, congenital torticollis, chronic torticollis, or acquired torticollis, idiopathic or secondary. The last implies a chronic etiology, often of a structural nature (eg, odontoid fracture, cystic mass, cervical adenitis). Some of the more common causes include congenital problems, trauma, and infections. [2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

Pathophysiology

Congenital torticollis

Congenital muscular torticollis is rare (< 2%) and is believed to be caused by local trauma to the soft tissues of the neck just before or during delivery. [7] The most common explanation involves birth trauma to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, resulting in fibrosis or that intrauterine malpositioning leads to unilateral shortening of the SCM. [12] There may be resultant hematoma formation followed by muscular contracture. These children often have undergone breech or difficult forceps delivery.

The fibrosis in the muscle may be due to venous occlusion and pressure on the neck in the birth canal because of cervical and skull position. Another hypothesis includes malposition in utero resulting in intrauterine or perinatal compartment syndrome. Other causes of congenital torticollis include postural torticollis, pterygium colli (webbed neck), SCM cysts, vertebral anomalies, odontoid hyperplasia, spina bifida, hypertrophy or absence of cervical musculature, and Arnold-Chiari syndrome. It can also be seen with clavicular fractures, especially in neonates secondary to birth trauma. Up to 20% of children with congenital muscular torticollis have congenital dysplasia of the hip as well. [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

Acquired torticollis

The pathophysiology of acquired torticollis depends on the underlying disease process. Cervical muscle spasm causing torticollis can result from any injury or inflammation of the cervical muscles or cranial nerves from different disease processes.

Acute torticollis can be the result of blunt trauma to head and neck, or from simply sleeping in an awkward position. Acute torticollis may be self-limited in days to weeks or the result of idiosyncrasy to certain medications (eg, traditional dopamine receptor blockers, metoclopramide, phenytoin, or carbamazepine.) After stopping medication, it quickly resolves without further action. After the resolution of acute traumatic torticollis, a chronic or persistent form may reappear after days or weeks of a quiescent interval. This situation often has legal implications regarding liability associated with the acute traumatic incident.

Atlantoaxial rotary subluxation (AARS) of C1 on C2 is important to consider and leads to a presentation similar to torticollis. It is predominant in children and generally occurs after minor trauma, pharyngeal surgery, an inflammatory process, or upper respiratory tract infection. It is thought to be precipitated by retropharyngeal edema leading to laxity of ligaments and structures at the atlantoaxial level, permitting the rotational deformity. In contrast to congenital muscular torticollis, the head tilts away from the affected SCM muscle. Known as the "cock robin" position, the head is rotated to the side opposite the facet dislocation and laterally flexed in the opposite direction. [20] Patients may also complain of unilateral occipital pain. AARS can also be a result of torticollis, although extremely rare.

Idiopathic spasmodic torticollis (IST) is a chronic, progressive form of torticollis classified as a focal dystonia. The etiology is unclear, although a thalamic lesion has been suspected. It is characterized by having an acquired, nontraumatic origin consisting of episodic tonic and/or clonic involuntary contractions of neck muscles. Symptoms last more than 6 months and result in considerable somatic and psychologic disability.

Benign paroxysmal torticollis is a self-limited condition common in infants characterized by repetitive episodes of head tilting with vomiting, pallor, irritability, ataxia, or drowsiness and usually presents in the first few months of life. Episodes can alternate sides. It is thought to be a migraine equivalent disorder, with some cases associated with underlying channelopathy.

Basal ganglia circuit abnormalities

As a neurodegenerative disease, torticollis, or idiopathic cervical dystonia, is believed to arise from basal ganglia circuit abnormalities stemming from selective vulnerability of these structures to an abnormal biochemical process that leads to neuronal dysfunction. Some indication of involvement of dopamine-secreting circuits comes from findings of low levels of metabolites of dopamine in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and some minor improvements reported from individual trials of levodopa and traditional neuroleptics, both of which possess equal D1 and D2 receptor-binding properties. Neither moderate-dose levodopa nor high-dose anticholinergics are as effective in idiopathic torsion dystonias as in inherited dystonias, which therefore have clearly different receptor responses and circuit abnormalities.

The use of selective D2 ligands with single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scanning in 10 patients with torticollis has shown reduced D2-receptor binding in the basal ganglia. [21] Similar results have been noted in focal hand dystonia by using SPECT [22] and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning. [23] The implication is that underactivity occurs in the D2 dopamine receptors located in the indirect pallidal outflow pathway in both conditions. Such underactivity can be expected to cause disinhibited thalamocortical output and dystonic postures.

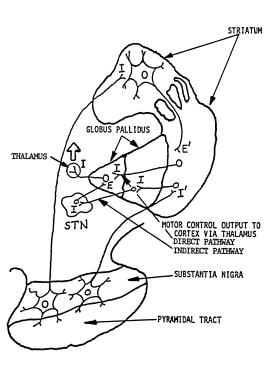

This relative imbalance between direct (D1-related) and indirect (D2-related) pallidal outflow pathways (see the image below) explains the failure of levodopa to adequately improve torticollis and the transient improvement from traditional neuroleptic agents, which initially may reduce D1 activity and eventually both D1 and D2 activity in both pathways.

Pallidal outflow pathways from basal ganglia to thalamus. E = excitatory; i = inhibitory; STN = subthalamic nucleus. Image courtesy of Norman C. Reynolds, MD, and Wisconsin Medical Journal.

Pallidal outflow pathways from basal ganglia to thalamus. E = excitatory; i = inhibitory; STN = subthalamic nucleus. Image courtesy of Norman C. Reynolds, MD, and Wisconsin Medical Journal.

Pramipexole is a dopamine agonist with selective, highly potent binding properties to D2 and D3 receptors. The authors have tried pramipexole in an open label trial in 14 patients with idiopathic cervical dystonia who displayed uncomplicated torticollis (unpublished results). Reduction in stiffness of neck muscles and head movements was reported in 6 patients who received 1.5 mg 3 times per day for at least 2 years. Five of 8 patients improved on 5 mg olanzapine, a dopamine-receptor blocker with minimal D1-blocking potency compared with its major D2- and D3-blocking potency. Atypical neuroleptic action suggests a bilateral relative binding effect, in which blocking the D2 action on the opposite indirect pathway may enhance the ipsilateral D2 receptor effect by comparison. This observation may suggest a mechanism of bilateral rather than unilateral basal ganglia control of torticollis.

Another approach to increasing the inhibitory output of the indirect pathway (an alternative to increasing D2 receptor action in the same pathway) is to deplete or block glutamate action. Selective glutamate release inhibition can be achieved with riluzole or with glutamate receptor blocking with amantadine, lamotrigine, or memantine.

Although the D3 activity of pramipexole has been linked to improvement in mood, [24] D3 receptors are also found in the striatum of the basal ganglia and may provide a role complementary to the expected increased activity in the indirect pathway provided by D2 action of the drug. The action of the atypical neuroleptics such as olanzapine or risperidone is quite interesting and needs far more extensive evaluation before a mechanism of rebalance can be offered.

Further studies of receptor binding are needed to clarify the unknown process leading to the slow evolution and progression of torticollis. Such understanding is also necessary in providing viable medication alternatives to repeated botulinum toxin injections every few months and the surgical alternatives offered in cases of injection failure.

Etiology

Because idiopathic cervical dystonia is a neurodegenerative process, the confluence of etiologic factors in modern popular explanations applies here as it does in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Patients have a genetically determined susceptibility to environmental toxins, which, if encountered in threshold doses, activate free radical production in susceptible brain regions, leading to neuronal deterioration.

Because both idiopathic and delayed posttraumatic cervical dystonia wax and wane with emotional tone, the patient may believe an unjustified assertion that the dystonic problem is psychiatric in nature. This belief is easily reinforced by others who are not medically trained and actually was presumed by medical practitioners before the advent of synaptic chemistry and neurophysiology.

Occasionally, torticollis with dystonic components or major cervical dystonia occurs as part of the overall clinical picture of Parkinson disease. The entire degenerative disease process should not be considered 2 processes but rather 1 process (ie, Parkinson disease). When head tremors without dystonic components occur with postural tremors of the upper extremities, consider the entire syndrome essential tremor. When torticollis with dystonic components occurs with postural tremors of the upper extremities, regard the entire syndrome as a form of cervical dystonia.

Nondystonic torticollis can occur as an abnormal head position due to spinal deformity. In these patients, no palpable muscle hypertonus or hypertrophy and no record of sensory tricks should be present.

Local etiology in adults and children

In adults, acute wryneck is the most prevalent type of torticollis and develops overnight without provocation. It is self-limited, and symptoms resolve in 1-2 weeks.

Any abnormality or trauma of the cervical spine can present with torticollis. Trauma, including minor trauma (sprains/strains), fractures, dislocations, and subluxations, often result in spasms of cervical musculature. Other causes may involve infection, spondylosis, tumor, scar tissue, or ligamentous laxity in the atlantoaxial region. Spinal epidural hematomas are a potential life-threatening cause to consider. Torticollis also rarely presents secondary to intervertebral disk calcifications, cervical spine tumors, spondylitis, arteriovenous malformations, and other bony abnormalities.

Upper respiratory and soft-tissue infections of the neck can cause an inflammatory torticollis secondary to muscle contracture or adenitis. Torticollis has been associated with retropharyngeal abscesses and is important to consider, because it is potentially life-threatening. [25, 26] It is most commonly seen in children aged 2-4 y, but the incidence in adults is increasing. Patients typically present with neck discomfort, fever, stridor, dysphagia, drooling, odynophagia, and respiratory distress.

Torticollis may also occur from infection following trauma or any infection involving surrounding tissue or structures of the neck including pharyngitis, tonsillitis, epiglottitis, sinusitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, nasopharyngeal abscess (see the image below), and upper lobe pneumonias.

Pediatric local etiology may include the following:

-

Congenital causes, such as pseudotumor of infancy, hypertrophy or absence of cervical musculature, spina bifida, hemivertebrae, and Arnold-Chiari syndrome

-

Otolaryngologic causes, such as vestibular dysfunction, otitis media, cervical adenitis, pharyngitis, retropharyngeal abscess, and mastoiditis

-

Esophageal reflux, particularly if episodic (ie, Sandifer syndrome)

-

Syrinx with spinal cord tumor

-

Traumatic causes, such as birth trauma, cervical fracture or dislocation, and clavicular fractures

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, with associated risk of atlanto-axial subluxation

Compensatory etiology in adults and children

Torticollis is also often seen as a compensatory mechanism for another disease or symptoms. Patients present with a head tilt to compensate for an essential head tremor or for diplopia secondary to an ocular muscle or nerve palsy.

Pediatric patients need a thorough eye examination to rule out a cranial nerve palsy or congenital nystagmus. Pediatric compensatory etiologies may include the following:

-

Strabismus with fourth cranial nerve paresis

-

Congenital nystagmus

-

Posterior fossa tumor

Central etiology in adults and children

Torticollis often presents as a dystonic reaction secondary to medications including phenothiazines, metoclopramide, haloperidol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and L-dopa therapy. Dystonic reactions cause acute muscle spasms of certain muscle groups often resulting in torticollis, trismus, fixed upper gaze, grimace, clenched jaw, and difficulty with speech. It is treated with diphenhydramine or benzodiazepines.

Idiopathic spasmodic torticollis occurs more frequently in females, and onset typically occurs in those aged 30-60 years. [27]

Pediatric central etiology dystonias include torsion dystonia, drug-induced dystonia, and cerebral palsy. [28]

Epidemiology

Reports of torticollis incidence are available primarily from the United States and Canada. Posttraumatic cases account for 10-20% of cases; the others are idiopathic. Consky and Lang reviewed several series to determine the relative frequency of torticollis types, with the following conclusions [29] :

-

Most cases of torticollis have mixtures of movements

-

Spasmodic features presumably dominate and relate to the classic descriptor of head jerks and spasms, hence the term spasmodic torticollis (no consensus exists regarding that description; the term cervical dystonia is preferred)

-

Torticollis with some degree of rotation is the most common individual type

-

After rotational torticollis in frequency come laterocollis and then retrocollis, with anterocollis being the rarest form

Although no racial predominance is reported for torticollis, females are affected twice as often as males, [30] and there are age-related differences. Onset of idiopathic cervical dystonia typically occurs when patients are aged 30-50 years (average age of onset, 40 y). Onset of posttraumatic cervical dystonia is within days of injury for the acute form and 3-12 months after injury for the delayed form. Congenital muscular torticollis occurs in less than 0.4% of newborns. [7]

Prognosis

Torticollis conditions do not usually lead to death, and the life span of affected individuals is normal. However, morbidity from this condition concerns 3 areas that may require additional treatment:

-

Chronic pain due to dystonia or strain in attempts to compensate for abnormal postures

-

Cervical spondylosis from chronic abnormal dystonic posture, which can lead to radiculopathies and/or spinal stenosis

-

Social embarrassment or the extreme of social isolation with depression

Ninety percent of patients with congenital muscular torticollis respond to passive stretching within the first year of life. For patients who undergo selective denervation, 65-80% experience satisfactory results, and these patients can be expected to maintain their improvement. No long-term prognosis for sternocleidomastoid release is available in the current literature.

Patient Education

Patients must understand that their condition is expected to wax and wane with emotions and that this phenomenon does not make their condition a psychologic problem.

Patient electromagnetic field precautions

Patients must be wary of any interaction with major electromagnetic fields associated with electrical generators in industrial applications, field detectors used in library screening to prevent book stealing, and metal detectors in general. Preflight check-in to airlines or other security checkpoints should avoid electromagnetic probes or wands that can turn off the deep brain stimulator (DBS). Nevertheless, the patient has a handheld magnetic trigger and can either turn on or off the pacemaker controller.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has special considerations because of massive fluctuations of magnetic fields that can cause the generator to cycle on and off. Before scanning, the pacemaker should be turned off (the patient can do this), and the amplitude setting of the controller should be set to zero (done by a physician or technician with special interrogator needs). Recycling at zero amplitude is not problematic.

Similar issues occur if electroconvulsive therapy is anticipated. When electric cardioversion is needed in a cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) emergency, postsurvival adjustments can be made to maximize motor performance and the status of the DBS being on or off should not detract from needed lifesaving measures.

Activity

Certain motor activities or prolonged postural vocational requirements may exacerbate pain. An ergonomics evaluation in the workplace can be helpful. Changing or selecting positions can also be beneficial (ie, sitting to the left or the right of a speaker to avoid cervical strain).

-

Female patient presenting with torticollis. Image courtesy of Danette C Taylor, DO, MS.

-

Female patient presenting with torticollis. Image courtesy of Danette C Taylor, DO, MS.

-

Female patient presenting with torticollis. Image courtesy of Danette C Taylor, DO, MS.

-

A 69-year-old woman presents with torticollis and a fever.

-

Pallidal outflow pathways from basal ganglia to thalamus. E = excitatory; i = inhibitory; STN = subthalamic nucleus. Image courtesy of Norman C. Reynolds, MD, and Wisconsin Medical Journal.

-

Soft-tissue neck radiograph demonstrates retropharyngeal abscess appearing as torticollis.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Anticholinergics

- Antiparkinson Agents, Dopamine Agonists

- Neurologics, Other

- Beta-Blockers, Nonselective

- Anticonvulsants, Other

- Antiparkinson Agents, Anticholinergics

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agents (NSAIDs)

- Neuromuscular Blockers, Botulinum Toxins

- Antispastic/Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Inhibitors

- Anxiolytics, Benzodiazepines

- Antipsychotics, 2nd Generation

- Show All

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- References