Practice Essentials

Low back pain is essentially a modern-day pandemic, with chronic low back pain (LBP) being the second leading cause of adult disability in the United States. [1] The symptoms of degenerative lumbar spine disease can broadly be divided into two broad categories: (1) LBP and (2) radicular symptoms in the lower extremities, which in some cases lead to neurogenic claudication. In terms of the pathology, the common subgroups of LBP of intervertebral disk origin include the following:

Disk herniation, though more frequently encountered in the lumbar spine, is fairly common in the cervical spine as well and may also be seen, albeit less commonly, in the thoracic spine. In principle, disk herniation represents the failure of the tensile anulus fibrosus to keep the inner nucleus pulposus contained; as a result, the nucleus becomes herniated, leading to the subsequent manifestation of clinical symptoms.

The symptoms due to herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) can ultimately be attributed to the significant inflammatory response it generates inside the spinal canal. Disk injury results in an increase in the proinflammatory molecules interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Macrophages respond to this displaced foreign material and seek to clear the spinal canal. Subsequently, a significant scar is produced, even without surgery, and substance P, which is associated with pain, is detected.

Apart from this inflammatory cascade that ensues, disk herniation also results in a definite mechanical neural compression that is responsible for dysfunction of the compressed nerve root. Symptoms may be motor (weakness along a myotome) or sensory (numbness/paraethesias across a dermatome). In severe cases, loss of bladder or bowel control may ensue; this is known as the cauda equina syndrome. Inflammation of the nerve contributes just as much to the radicular pain as mechanical compression does, and this explains the lack of correlation between the actual size of an intervertebral disk herniation or even the consequent degree of neural compression and the associated clinical symptoms. [4]

Smoking is one of the most important risk factors behind disk herniation. Lumbar disk herniation may result from chronic coughing and other stresses on the disk. For example, sitting without lumbar support causes an increase in disk pressures, and driving is also a risk factor because of the resonant coupling of 5-Hz vibrations from the road to the spine. People who drive significant amounts have increased spinal problems; truck drivers have the additional risk of spinal problems from lifting during loading and unloading, which, unfortunately, is done after prolonged driving.

Studies showed that peak stresses within a deteriorated intervertebral disk exceed those from average loads on a normal disk, which is consistent with a pain mechanism. Further repetitive stress at physiologic levels did not produce a herniation after prolonged testing, contradicting the concept of injury accumulation with customary work activities. However, after a simulated injury to the anulus (cutting), a lower mechanical stress did result in disk herniation, consistent with intervertebral disk degeneration and with clinical experience on diskography.

The presumed traumatic cause of disk herniations has been questioned scientifically in the literature, particularly with the increased availability of genetic information. [5, 6] The pathologic state of a weakened anulus is a necessary condition for herniation to occur. Many cases involve trivial trauma even in the presence of repetitive stress. An anular tear or weak spot has not been demonstrated to result from repetitive normal stress from customary activities or from physically stressful activities.

Mixter and Barr first recognized that the cartilaginous masses in the spinal canal of their patients were not tumors or chondromas. [7] They proposed that herniation of the nucleus pulposus and displacement of nuclear material caused neural irritation, inflammation, and pain. They showed that excising a disk fragment was effective, but their recommendation to perform this procedure with a fusion was necessitated by relatively aggressive laminectomy. This procedure has been replaced by techniques that are less invasive, such as microdiskectomy.

Bed rest has a long history of use but has not been shown to be effective beyond the initial 1 or 2 days; after this period, it is counterproductive. All conservative treatments are essentially efforts to reduce inflammation. Therefore, only a very short period of rest is appropriate; anti-inflammatories are of some benefit, and warm, moist heat or modalities may help. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonism was experimentally shown to decrease inflammatory events in preclinical models.

Long-term use of physical therapy modalities is no more effective than hot showers or hot packs are at home. A transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit may be subjectively helpful in some patients with chronic conditions. Patients should be encouraged essentially to compensate for intervertebral disk incompetence, to the extent possible, by means of muscular stabilization, as well as to maintain flexibility by initiating lifelong exercise regimens.

The various surgical procedures reported have the common goal of decompressing the neural elements to relieve the leg pain. These procedures are most appropriate for patients with minimal or tolerable back pain who have an essentially intact and clinically stable disk. However, the hope of permanently relieving the back pain is a fantasy—a false hope.

The most common procedure for a herniated or ruptured intervertebral disk has been microdiskectomy, and many patients who undergo this procedure can be discharged with minimal soreness and complete relief of leg pain after overnight admission and observation. Same-day procedures are in the process of cautious development. Patients with dominant back pain have a different problem, even if HNP is present, and would require stabilization by fusion if unresponsive to well-managed appropriate therapy or arthroplasty. Minimally invasive techniques generally fall into two broad categories: central decompression of the disk and directed fragmentectomy.

Anatomy

The intervertebral disk is the largest avascular structure in the body. It arises from notochordal cells between the cartilaginous endplates, which regress from about 50% of the disk space at birth to about 5% in the adult, with chondrocytes replacing the notochordal cells.

Intervertebral disks are located in the spinal column between successive vertebral bodies and are oval in cross-section. Their height increases from the peripheral edges to the center, appearing as a biconvex shape that becomes successively larger by about 11% per segment from cephalad to caudal (ie, from the cervical spine to the lumbosacral articulation). A longitudinal ligament attaches to the vertebral bodies and to the intervertebral disks anteriorly and posteriorly; the cartilaginous endplate of each disk attaches to the bony endplate of the vertebral body. (See the images below.)

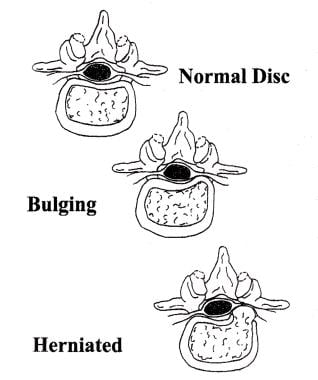

Nuclear material is normally contained within anulus, but it may cause bulging of anulus or may herniate through anulus into spinal canal. This commonly occurs in posterolateral location of intervertebral disk, as depicted.

Nuclear material is normally contained within anulus, but it may cause bulging of anulus or may herniate through anulus into spinal canal. This commonly occurs in posterolateral location of intervertebral disk, as depicted.

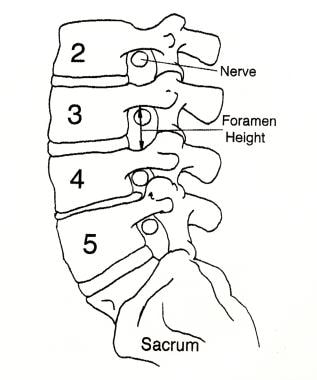

Spinal nerves exit spinal canal through foramina at each level. Decreased disk height causes decreased foramen height to same degree, and superior articular facet of caudal vertebral body may become hypertrophic and develop spur, which then projects toward nerve root situated just under pedicle. In this picture, L4-5 has loss of disk height and some facet hypertrophy, thereby encroaching on room available for exiting nerve root (L4). Herniated nucleus pulposus within canal would embarrass traversing root (L5).

Spinal nerves exit spinal canal through foramina at each level. Decreased disk height causes decreased foramen height to same degree, and superior articular facet of caudal vertebral body may become hypertrophic and develop spur, which then projects toward nerve root situated just under pedicle. In this picture, L4-5 has loss of disk height and some facet hypertrophy, thereby encroaching on room available for exiting nerve root (L4). Herniated nucleus pulposus within canal would embarrass traversing root (L5).

The disc's anular structure is composed of an outer anulus fibrosus, which is a constraining ring that is composed primarily of type 1 collagen. This fibrous ring has alternating layers oriented at 60° from the horizontal to allow isovolumic rotation. That is, just as a shark swimming and turning in the water does not buckle its skin, the intervertebral disk has the ability to rotate or bend without a significant change in volume, so that the hydrostatic pressure of the inner portion of the disk (ie, the nucleus pulposus) is not affected.

The nucleus pulposus consists predominantly of type II collagen, proteoglycan, and hyaluronan long chains, which have regions with highly hydrophilic branching side chains. These negatively charged regions have a strong avidity for water molecules and hydrate the nucleus or center of the disk via an osmotic swelling pressure effect. The major proteoglycan constituent is aggrecan, which is connected by link protein to the long hyaluronan. A fibril network, including a number of collagen types along with fibronectin, decorin, and lumican, contains the nucleus pulposus.

The hydraulic effect of the contained hydrated nucleus within the anulus acts as a shock absorber to cushion the spinal column from forces that are applied to the musculoskeletal system. Each vertebra of the spinal column has an anterior centrum or body. The centra are stacked in a weightbearing column and are supported by the intervertebral disks. A corresponding posterior bony arch encloses and protects the neural elements, and each side of the posterior elements has a facet joint or articulation to allow motion.

The functional segmental unit is the combination of an anterior disk and the two posterior facet joints, and it provides protection for the neural elements within the acceptable constraints of clinical stability. The facet joints connect the vertebral bodies on each side of the lamina, forming the posterior arch. These joints are connected at each level by the ligamentum flavum, which is yellow because of the high elastin content and allows significant extensibility and flexibility of the spinal column.

Clinical stability has been defined as the ability of the spine under physiologic load to limit patterns of displacement so as to avoid damage or irritation to the spinal cord or nerve roots and to prevent incapacitating deformity or pain caused by structural changes. [8] Any disruption of the components holding the spine together (ie, ligaments, intervertebral disks, facets) decreases the clinical stability of the spine. When the spine loses enough of these components to prevent it from adequately providing the mechanical function of protection, surgery may be necessary to reestablish stability.

Pathophysiology

Degeneration: process and models

LBP is ubiquitous, with 60-80% of people having an activity-limiting episode at least transiently in their lifetime. Genetic factors appear to play a dominant role, with LBP starting at an earlier age than previously suspected on the basis of subsequent structural changes; men begin having LBP about a decade earlier than women do. [9]

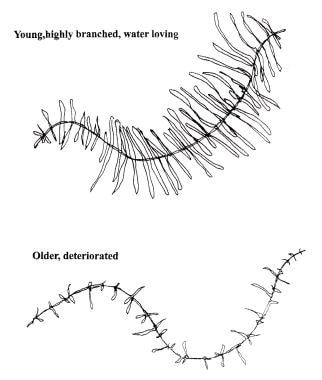

The water-retaining ability of the nucleus pulposus (the inner portion of the intervertebral disk) declines progressively with age. The decline in the mechanical properties of the nucleus pulposus is associated with the degree of proteoglycan deterioration and the decrease in hydration, which lead to excessive regional peak pressures within the disk. As the hyaluronan long chains shorten and swelling pressure decreases as a result of this deterioration, the mechanical stiffness of the disk decreases, which causes the anulus to bulge, with a corresponding loss of disk and foramen height. [10] (See the image below.)

Hyaluronan long chains form backbone for attracting electronegative or hydrophilic branches, which hydrate nucleus pulposus and cause swelling pressure within anulus to allow it to stabilize vertebrae and act as shock absorber. Deterioration within intervertebral disk results in loss of these water-retaining branches and eventually in shortening of chains.

Hyaluronan long chains form backbone for attracting electronegative or hydrophilic branches, which hydrate nucleus pulposus and cause swelling pressure within anulus to allow it to stabilize vertebrae and act as shock absorber. Deterioration within intervertebral disk results in loss of these water-retaining branches and eventually in shortening of chains.

The etiology of back pain for a particular individual cannot be determined, because of the multiplicity of potential sources. Although periosteal disruption causes pain with fractures, bone itself is devoid of pain receptors (eg, asymptomatic compression fractures commonly are seen in the thoracic spine of elderly individuals with osteoporosis). However, the degenerating intervertebral disk is known to have neurovascular elements at the periphery, including pain fibers.

Disk deterioration and loss of disk height may shift the balance of weightbearing to the facet joint; this mechanism has been hypothesized as a cause of LBP through the facet-joint capsule, as well as through other tissues attached to and between the posterior bony elements.

When the anulus is incised in animals, a degenerative cascade is initiated that mimics the natural aging process observed in humans, thus providing a model of disk deterioration. [11] As the use of diskography has increased for various clinical applications, similar anular tears are seen routinely that are associated with the degeneration of the intervertebral disk, even in patients who are asymptomatic. Anular tears may simply be the result of aging and the degenerative cascade.

Pathology studies of young patients who died as a result of trauma reveal a surprising degree of articular surface damage in the facet joints; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) routinely reveals disk deterioration in individuals in the second or third decade of life. Injection of chymopapain into the intervertebral disk causes a repeatable and predictable degenerative cascade in the facet joints, illustrating the coupling between the disk and the facet joints. Immobilization by facet fusion posteriorly leads to disk deterioration; this avascular structure is solely dependent upon motion to facilitate the diffusion of nutrients into it.

Whether the deterioration of the disk or that of the facet comes first has not been determined; however, deterioration is known to occur in both.

Dehydration results from shortening of the hyaluronic chains, deterioration of the state of aggregation, and decreases in the ratio of chondroitin sulfate to keratan sulfate, leading to disk bulging and loss of disk height. The consistency of the nuclear material undergoes a change from a homogeneous material to clumps, which leads to the altered distribution of pressures within the disk and resistance to the flow of nuclear material; the nuclear material thereby becomes mechanically unstable. [12] The clumping of the degenerating nuclear material can be likened to a marble held between two books—that is, it is difficult to contain.

These clumps may be lateral to the posterior longitudinal ligament and therefore may have the least resistance to herniating through the corner of the intervertebral disk and into the spinal canal or foramen. Surgical removal of the herniated fragments is achieved by grasping them with a pituitary rongeur.

This method of surgical removal is not possible with normal homogeneous material, which is encountered when healthy intervertebral disks are excised anteriorly in patients undergoing surgery because of deformity or trauma. Using the pituitary rongeur technique to perform a microdiskectomy on a herniated fragment requires a preexisting state of deterioration; the weakened areas in the anulus provide a path of least resistance for egress of the nuclear material.

Natural history

Much has been written concerning the process of spinal deterioration or spondylosis, which occurs over a lifetime. Intervertebral disk deterioration leads to decreased stiffness of the disk, as well as diminished stability, resulting in episodic pain that is common and may be temporarily severe. However, continued deterioration ultimately leads to restabilization of the spine by collagenization, which stiffens the disk. Patients in their 50s and 60s customarily have stiffer spines but less pain than patients in their 30s and 40s who are undergoing initiation of the degenerative cascade.

Patients who ask if they have to live with this pain for the rest of their lives can be reassured to some extent by this natural history. Furthermore, spontaneous recovery from an acute pain episode routinely occurs; thus, for any treatment to be demonstrated as effective, it must positively alter the expected course without treatment.

In general practice, the overall incidence of HNP in patients who have new-onset LBP is lower than 2%. Therefore, most of these patients have deterioration of the intervertebral disk and dysfunction of the functional segmental unit. They will have LBP, and some will have associated leg pain but without sciatica (an intractable, radiating pain below the knee) or radiculopathy. A disk fragment that is no longer contained within the anulus but is displaced into the spinal canal has decreased hydration and deteriorated proteoglycan that can be expected to undergo further deterioration and consequent anular desiccation, essentially resembling a grape being transformed into a raisin.

Spontaneous resolution of sciatica may result from shrinkage of a herniated fragment, aided by macrophages and the evoked inflammatory reaction, but practitioners too often attribute this clinical improvement to their favorite treatments. Intractable symptoms of sciatica from intervertebral disk displacements may benefit dramatically from surgical intervention.

Within 20 years of Mixter and Barr's 1934 report, Friedenberg compared operative treatment with nonoperative treatment. [7, 13] Nonoperative treatment yielded three groups of results: pain-free, occasional residual pain, and disabling pain. Proportions of these groups remained similar after 5 years. Friedenberg concluded that even recurrent severe episodes may resolve without surgery; the problem was and remains patient selection.

Weber presented a randomized, controlled study (marred by dropouts in the surgery control group because of severe pain) and concluded that patient results were the same with operative as with conservative treatment, except that those who were treated operatively had better results at 1 year. [14]

The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort was similarly limited in its conclusions by crossovers: 50% of the surgery arm had surgery within 3 months and 30% of the nonsurgical group had surgery, but at long-term follow-up, the two groups again were not statistically different. [15]

Prognosis

Patients with "broad-based" intervertebral disk herniations generally have a deterioration of the disk or a failure of clinical stability with associated back pain, rather than isolated sciatica. These patients are not appropriate candidates for microdiskectomy alone.

Lumbar fusion is being used increasingly in these cases, and arthroplasty is also being considered; however, this treatment remains controversial because it is, again, based inevitably on subjective patient pain and clinical judgment without objective determination. Many reports in the literature have described specific cytokines elevated, but not comprehensively; endplate changes are observed, but no clear correlation is identified to this point. Various nuclear replacements that reduce postoperative loss of disk height and restore compressive loading are being studied. [16]

With a diskectomy, patients with dominant leg pain have excellent results, with 85-90% returning to full function. However, as many as 15% of patients have continued back pain that may limit their return to full function, despite the absence of radiculopathy. Patients who undergo surgery do not necessarily show better results than those who defer surgery. [17]

The remaining concern of recurrent herniation is small, though it is correlated with obesity. [18] Efforts to minimize this complication have included anulus repair [19] and injection of hemostatic materials or bioactive molecules. Etanercept was shown in a small study to be of no benefit for sciatica, though the addition of butorphanol with corticosteroid was helpful with an epidural injection. [20]

Intervertebral disk degeneration that causes clumping of the nuclear material and relative mechanical instability is the necessary preceding condition for HNP. However, it is impossible to tell which patients will do well after microdiskectomy for a herniation and which will have continued problems, of varying severity, from the disk degeneration. Studies have shown that degenerated disks have different growth factors and other molecules; thus, even introducing mesenchymal stem cells requires significant further research and development. [21]

Significant deterioration and accompanying LBP increasingly are being treated with stabilization, via either an anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) or a posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) in association with posterior decompression (when necessary) and instrumentation. Techniques continue to evolve, and conclusive results remain to be determined.

Tomasino et al presented radiologic and clinical outcome data on patients who underwent single-level anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF) for cervical spondylosis or disk herniation with the use of bioabsorbable plates for instrumentation. [22] Overall, at 19.5 months postoperatively, 83% of the patients had favorable outcomes according to the Odom criteria.

The authors found that absorbable instrumentation provides better stability than the absence of a plate but that graft subsidence and deformity rates may be higher than those associated with metal implants. [22] In this study, the fusion rate and outcome were found to be comparable to the results achieved with metallic plates, and the authors concluded that the use of bioabsorbable plates is a reasonable alternative to metal, avoiding the need for lifelong metallic implants.

Buchowski et al performed a cross-sectional analysis of two large prospective randomized multicenter trials to evaluate the efficacy of cervical disk arthroplasty for myelopathy with a single-level abnormality localized to the disk space. [23] Both patients in the arthroplasty group and those in the arthrodesis group had improvement after surgery, with improvement being similar and with no worsening of myelopathy occurring in the arthroplasty group. Although the findings at 2 years after surgery suggested that arthroplasty is equivalent to arthrodesis in these cases, the authors did not evaluate treatment of the retrovertebral compression that occurs with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Carragee et al compared progression of common degenerative findings between lumbar disks injected 10 years previously and those same disks in matched subjects who were not exposed to diskography. [24] In all graded or measured parameters, disks exposed to puncture and injection showed greater progression of degenerative findings than control (noninjected) disks did (35% vs 14%), with 55 new disk herniations occurring in the diskography group and 22 in the control group. There also was significantly greater loss of disk height and signal intensity in the diskography disks. The authors recommended careful consideration of risk and benefit in regard to disk injection.

McGirt et al performed a prospective cohort study using standardized postoperative lumbar imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 3 months for 1 year and annually thereafter to assess same-level recurrent disk herniation. [25] Improvement in all outcome measures was observed 6 weeks after surgery. At 3 months after surgery, 18% loss of disk height was observed, which progressed to 26% by 2 years. In 11 (10.2%) patients, revision diskectomy was required at a mean of 10.5 months after surgery.

In this study, [25] patients who had larger anular defects and removal of smaller disk volumes had an increased risk of recurrent disk herniation, and those who had greater disk volumes removed had more progressive disk height loss by 6 months after surgery. The authors suggested, on the basis of these findings, that in cases of larger anular defects or less aggressive disk removal, concern for recurrent herniation should be increased and that effective anular repair may be helpful in such cases.

Fish et al performed a retrospective single-center study to analyze whether MRI findings could be used to predict therapeutic responses to cervical epidural steroid injections (CESI) in patients with cervical radiculopathy. [26] Patients were categorized by the presence or absence of four types of cervical MRI findings: disk herniation, nerve-root compromise, neuroforaminal stenosis, and central-canal stenosis. Only the presence, versus the absence, of central-canal stenosis was associated with significantly superior therapeutic response to CESI. The authors therefore concluded that the MRI finding of central-canal stenosis is a potential indication that CESI may be warranted.

Hirsch et al systematically reviewed the literature to determine the effectiveness of automated percutaneous lumbar diskectomy (APLD). [27] The authors noted that according to United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) criteria, the indicated evidence for APLD is level II-2 for short- and long-term relief, indicating that APLD may provide appropriate relief in properly selected patients with contained lumbar disk prolapse. However, the authors also noted that there was a paucity of randomized, controlled trials in the literature covering this subject.

Dasenbrock et al performed a meta-analysis of six trials (N = 837) comparing open diskectomy with minimally invasive diskectomy and found similar visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at short- and long-term follow-up. [28] No significant difference between the two approaches was apparent with regard to relief of leg pain. Reoperation was more common with limited (tubular) exposure, but the difference was not statistically significant. Total complications did not differ.

Yamaya et al assessed early outcomes of transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic lumbar diskectomy in 18 high school athletes (14 male, 4 female) with lumbar HNP. [29] All factors assessed by questionnaire—time to return to competitive sport, complications, and rate of recurrence of herniation—were significantly improved after the procedure, and the VAS score was improved as well. There were no complications (eg, dural tear, exiting nerve root injury, or hematoma), and one patient had a recurrence of HNP.

A retrospective single-center study by Harada et al evaluated the application of machine learning techniques to predict disk reherniation after lumbar diskectomy. [30] The authors found preoperative leg VAS score, disability, alignment parameters, elevated body mass index, symptom duration, and age to be the strongest predictors of recurrent HNP. On the basis of these findings, they developed the reherniation after decompression (RAD) profile index as screening tool for identifying patients at low or high risk patients for HNP recurrence; this tool will require additional validation before it can be broadly implemented.

-

Hyaluronan long chains form backbone for attracting electronegative or hydrophilic branches, which hydrate nucleus pulposus and cause swelling pressure within anulus to allow it to stabilize vertebrae and act as shock absorber. Deterioration within intervertebral disk results in loss of these water-retaining branches and eventually in shortening of chains.

-

Nuclear material is normally contained within anulus, but it may cause bulging of anulus or may herniate through anulus into spinal canal. This commonly occurs in posterolateral location of intervertebral disk, as depicted.

-

Spinal nerves exit spinal canal through foramina at each level. Decreased disk height causes decreased foramen height to same degree, and superior articular facet of caudal vertebral body may become hypertrophic and develop spur, which then projects toward nerve root situated just under pedicle. In this picture, L4-5 has loss of disk height and some facet hypertrophy, thereby encroaching on room available for exiting nerve root (L4). Herniated nucleus pulposus within canal would embarrass traversing root (L5).

-

Appearance of lumbar disk herniation on MRI.