Practice Essentials

Meralgia paresthetica is a common but underrecognized condition that is manifested by pain, numbness, and tingling in the anterior and lateral parts of the thigh. [1]

Bernhardt first described symptoms corresponding to meralgia paresthetica in 1878. In 1885, Hagar correctly suggested that compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) was the source of this symptom complex; surgical correction of meralgia paresthetica also dates back to Hagar. A decade later, Roth coined the term meralgia paresthetica from the Greek words meros (thigh) and algos (pain). Anecdotally, Sigmund Freud is said to have diagnosed himself and his son with this condition.

Entrapment of the LFCN results in pain and sensory abnormalities in the anterolateral thigh. This nerve is a pure sensory nerve that typically receives its innervation from the L2-L3 lumbar nerve roots and includes sudomotor fibers. Sudomotor changes, such as mild sweating in the nerve distribution, may be evident, though this is uncommon. Because the LFCN is purely sensory, no associated motor or reflex findings should be present. [2, 3]

Treatment is directed toward identification and relief of the compressive force on the LFCN. (See Treatment.) In many instances, the nerve spontaneously heals if the compression is relieved. If symptoms continue, anti-inflammatory medications, local injection, and other nonsurgical modalities may be considered. If these methods fail, surgery may be an option.

As physicians and patients become increasingly aware of meralgia paresthetica and as new medications and surgical techniques develop, the diagnosis and initiation of a treatment plan will be made more rapidly. Patients and physicians alike would benefit from an algorithm guiding diagnosis and treatment.

Anatomy

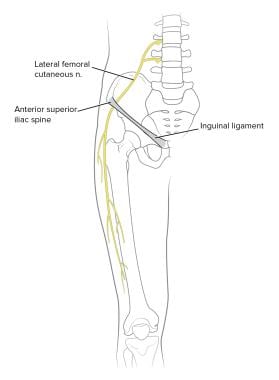

The LFCN typically arises from lumbar nerve roots, specifically those at the L2-L3 levels, though it can arise from different combinations of the L1-L3 nerve roots. The LFCN pierces the psoas, travels across the iliacus toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and then enters the anterolateral thigh by passing under, through, or above the inguinal ligament. (See the images below.) It is surrounded by a fascial canal. [4]

In most individuals, the LFCN crosses into the anterolateral thigh approximately 1 cm medial to the ASIS. However, the relation of the LFCN to the ASIS is quite variable. [4] The nerve may cross into the anterolateral thigh as much as 2 cm lateral or 6 cm medial to the ASIS. A bifurcation into anterior and posterior divisions occurs approximately 5-12 cm below the ASIS.

Cadaver dissections have demonstrated that anatomic variations are also found in the origin of the LFCN. As many as 30% of LFCNs may be derived partially or entirely from adjacent genitofemoral or femoral nerves.

Pathophysiology

Along its course, the LFCN is vulnerable to compression at several sites. The nerve emerges from the psoas muscle, intersects with the inguinal ligament, curves around the ASIS, and exits from the fascia lata. Meralgia paresthetica most commonly occurs from compression of the nerve as it exits the pelvis. [5, 6]

Peripheral nerve injuries are described in terms of the nature of the insult and the associated prognosis. Thus, a compressive force results in a neurapraxic injury to the nerve, which is characterized by the loss of myelin without affecting the axon or its axonal sheath. Neurapraxic injuries have the best prognosis and may heal over hours to months, depending on the severity.

Loss of the axon or its axonal sheath constitutes a more severe nerve injury and a worse prognosis for healing, because the nerve undergoes wallerian degeneration or destruction of the nerve fibers distal to the injury site. [7]

If the injury involves only the axons and spares the axonal sheath (axonotmesis), the patient may make a full, but likely slow, recovery. If the axonal sheath is affected so that the nerve is in discontinuity (neurotmesis), then the prognosis for spontaneous recovery is poor. Most commonly, compressive forces tend to result in neurapraxic injuries, and relief of the compressive force initiates the healing process.

Etiology

Metabolic conditions, such as diabetes, alcoholism, and thyroid disorders, can contribute to the development of a neuropathy in the LFCN and other peripheral nerves. In most instances, the etiology of meralgia paresthetica involves excessive pressure on the nerve at various sites of possible entrapment. Pressure may be from internal causes such as obesity, pregnancy, or pelvic tumors.

There is a higher incidence of obesity in patients with meralgia paresthetica, which strongly suggests that obesity is an independent risk factor. [8] Alternatively, an external cause (eg, tight belts worn around the waist) may be identified as the culprit. [9, 10] In addition, the LFCN may be injured iatrogenically from local trauma during surgical procedures. [11] Hip replacement, iliac crest bone grafting, appendectomy, inguinal lymph node dissection, aortofemoral bypass, uterine surgery, cesarean section, and quadriceps surgery have all been implicated as causative for meralgia paresthetica.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of meralgia paresthetica has been estimated at three cases per 10,000 individuals, and this condition has been reported in as many as 35% of patients referred for evaluation of leg discomfort. However, these symptoms often are not recognized or may be mistaken for other conditions (eg, lumbar radiculopathy). In a large case series, [12] the presumptive diagnosis by the referring physician was meralgia paresthetica in 47 of 120 patients (39%).

This condition has been described in toddlers and elderly persons, but most cases occur in patients aged 30-65 years. Whether a sex predominance exists is unclear. Meralgia paresthetica is usually unilateral but may be bilateral in as many as 50% of cases.

Prognosis

The outcome of therapy for meralgia paresthetica depends largely on whether the diagnosis and treatment plan are achieved within a reasonable time frame. The prognosis from conservative management alone is quite good because the condition often is self-limited. In 277 patients treated conservatively by Williams et al, 91% had satisfactory symptom relief. [13] In the worst-case scenario, patients treated conservatively had persistent symptoms such as pain, numbness, burning, hyposensitivity, and tingling in the anterolateral thigh.

Controversial issues have included the efficacy of surgery and the selection of a surgical procedure. In a study by van Eerten et al, [14] complete symptom relief was noted in three of 10 patients who underwent neurolysis and in nine of 11 patients who had a transection. Similarly, 23 of 24 patients who had a transection in Williams and Trzil's series [13] had complete relief of their presenting symptoms.

Ivins reported results for eight patients who underwent neurolysis; four experienced relief of symptoms, and two of the four had recurrence of their symptoms. [15] Siu and Chandran reported results from a case series of 45 decompressive procedures in 42 patients who underwent neurolysis: 43% reported complete relief, 40% reported partial relief, and 17% reported no relief. [16]

Although transection is more likely to produce complete relief, it likely will cause permanent anesthesia of the anterolateral thigh.

-

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) provides sensory innervation to anterolateral thigh. Courtesy of Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Hanley & Belfus Publishers, 2001, used with permission.

-

Anatomy of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN).

-

Sensory distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN).