Overview

Leprosy (Hansen disease) is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory disease caused primarily by the gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. Leprosy predominantly affects the skin, peripheral nerves, and eyes. Up to 75% of individuals with leprosy have ocular involvement, [1] and 40% have ocular disability. [2] Ocular manifestations include madarosis, lagophthalmos, corneal exposure, keratitis, corneal ulceration and scarring, episcleritis and scleritis, conjunctival and scleral lepromas, uveitis, uveal effusion, and retinal pearls and detachment. [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Ocular therapy depends on the manifestations of the disease and may involve medical and surgical measures.

Although leprosy was declared globally eliminated in 2000 (ie, prevalence of < 1 case per 10,000 persons globally), pockets of high endemicity still remain, primarily in a few developing countries (189,018 chronic cases and 232,857 new cases reported in 2012, according to the World Health Organization [8] ).

See Leprosy and Pediatric Leprosy for details about systemic leprosy.

Clinical Presentation

Since Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis cannot survive at body temperature, their ocular manifestations mainly involve the ocular adnexa and the anterior part of the globe. They can include the following:

-

Madarosis

-

Lagophthalmos (due to involvement of the seventh cranial nerve), exposure keratitis (secondary to lagophthalmos or to decreased corneal sensitivity due to involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic branch of the fifth cranial nerve), corneal ulcers and scars (secondary to exposure keratitis), keratic precipitates (dubbed lepromas), and corneal pannus and neovascularization

-

Iris pearls

-

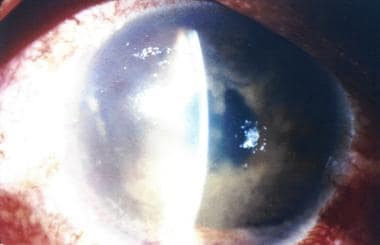

Acute or insidious and chronic anterior uveitis (see image below), with secondary cataract, anterior and posterior synechiae, and glaucoma or ocular hypotension [9]

-

Vitreous opacities.

-

Posterior involvement in rare cases, including peripheral anterior retinal pearls, retinal scars, uveal effusion, and retinal detachment

-

Phthisis bulbi in chronic cases

Chronologically, beading of the corneal nerves is probably the earliest detectable ocular finding (see image below). These abnormally wide edematous nerves are sometimes difficult to detect and are best seen with slit-lamp examination using a broad beam under retroillumination or sclerotic scatter. Beading results from the multiplication of bacilli in or adjacent to the nerves, with or without infiltration of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and epithelioid cells.

The immune system’s response to the invasion of the corneal nerves leads to the formation of lepromas (avascular punctate subepithelial opacities containing acid-fast organisms, lymphocytes, and macrophages). These milky chalky deposits, located between the epithelium and Bowman membrane, are best seen with slit-lamp examination. They can later spread, become confluent, calcify, and destroy Bowman membrane. This interstitial keratitis, usually bilateral, is pathognomonic of leprosy. As the disease progresses, a leprous pannus can form, usually starting at the superior limbus before extending around the entire corneal circumference. Superficial and deep vascularization of the cornea can also develop, interfering with the patient’s vision.

Patients may present with a sterile episcleritis due to the ongoing corneal inflammation, which is usually painful and circumcorneal. In the Carville Public Health Service (PHS) Hospital, 16% of the first ocular lesions noticed were episcleritis, scleritis, or uveitis. Late lepromas may also develop in the episcleral area.

Bacilli can then pass through the sclera or the cornea and invade the anterior chamber, the ciliary body, and the iris. Iris pearls with uveitis represent miliary lepromas and are diagnostic lesions (see image below). These creamy round spheres, usually measuring less than 0.5 mm in diameter, are typically located near the pupillary border or near the iridocorneal angle; they may also migrate and fuse with other pearls. Iris pearls contain acid-fast material, remains of lepromatous cellular debris, and calcium salts. They form deep in the iris stroma and are extruded to the surface, where they may persist for months or years.

Extension of the disease to the iris and to the ciliary body can lead to a severe and prolonged uveitis, which can be associated with extensive anterior or posterior synechiae. Repeated attacks usually lead to extensive iris atrophy and intractable secondary glaucoma.

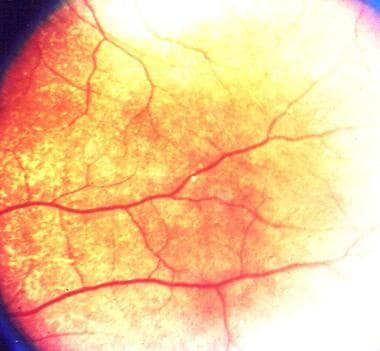

Although rare, uveal effusion in association with conjunctival and episcleral hyperemia (see first image below), as well as anterior peripheral retinal pearls (see second image below) and retinal detachment, may occur. At the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Hospital in San Francisco, the incidence of leprotic uveal infections in patients with Hansen disease is 6-7%.

Immunologically mediated leprosy type 1 reaction may mimic orbital or facial cellulitis. [10]

Diagnosis

Lagophthalmos (see image below) or unexplained seventh nerve weakness associated with skin and neurologic disorders should prompt the clinician to consider the diagnosis of Hansen disease, especially in patients originating from developing countries or living in poor socioeconomic conditions. Exposure keratitis and corneal ulceration, especially in association with decreased corneal sensitivity, thickened eyelids, incomplete blinking, decreased mucin and meibomian secretions, and denervation of the lacrimal gland, are also early clinical signs of leprosy.

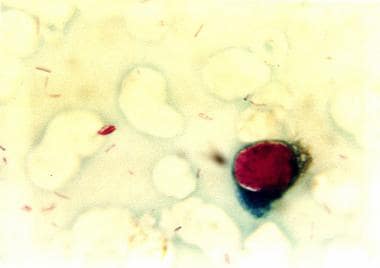

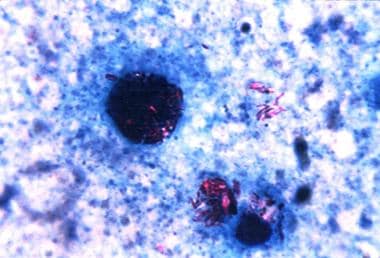

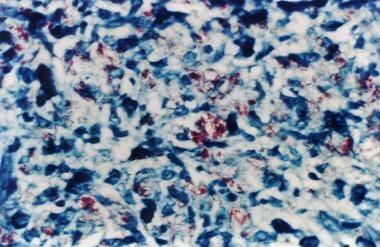

Typical systemic disease is confirmed by histopathology of corneal, conjunctival, or subcutaneous skin scrapings (see first image below), anterior chamber [11] or vitreous taps (see second image below), or skin tissue biopsy (see third image below). Histologic findings include multiple acid-fast bacilli with acid-fast or Fite-Faraco stains, along with iris pearls. In addition to histopathology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can also be used to diagnose leprosy.

Treatment & Management

Multidrug therapy should be prescribed as soon as possible to stop the progression of leprosy (see Leprosy). Depending on its ocular manifestations, targeted medical or surgical ocular therapy should be initiated, preferably under the care of an ophthalmologist.

Medical therapy

If present, aggressive treatment of uveitis is probably one of the most important considerations, as well as protection of a neurotrophic cornea from exposure, erosion, and ulceration, especially in the face of lagophthalmos.

Anterior uveitis should be treated aggressively with topical corticosteroids and mydriatic drops to avoid and break synechia and to prevent complications such as iris bombé, secondary glaucoma, and cataracts. Steroids should be tapered slowly. Note that the use of corticosteroids increases the risk for superinfection, particularly with trachoma and herpes, which are endemic in the regions where M leprae can be found; should the clinician suspect coincidental infection, it is advised to delay the use of steroids for a few days to treat this infection.

Corneal abrasion and ulcers should be treated with appropriate topical antibiotics. Frequent use of artificial tears or lubricating ointment is indicated in cases of exposure keratitis. Commercially available moisture shields, plastic wraps, or swimming goggles may also be used to prevent the eye from drying. Taping the eyelids shut at night is also useful, but care must be taken not to let part of the eye exposed, as this will increase the risk for exposure keratitis and corneal abrasion.

Finally, secondary glaucoma may be treated with topical anti-glaucomatous drops, as well as per os acetazolamide, to reduce intraocular pressure.

Surgical therapy

Cataracts may be surgically extracted. Note, however, that such a procedure should preferably be entertained be in the absence of uveitis.

Posterior synechia and glaucoma unresponsive to medical therapy may be treated with sector iridectomies. Trabeculectomies and tube shunts can also decrease the intraocular pressure. In patients who have a painful blind eye as a result of glaucoma, enucleation may be the treatment of choice.

Madarosis may be treated with makeup, tattooing, or free grafts from the scalp. Repeated epilation or electrolysis can be used to cure trichiasis, which may contribute to chronic keratitis if left untreated.

Lagophthalmos due to seventh nerve palsy may be treated with a partial tarsorrhaphy, lateral canthoplasty, or other lid-shortening procedures. Temporalis transfers are also useful in some patients. [12, 13]

Finally, entropion or ectropion should be surgically corrected if they contribute to keratitis, or for aesthetic purposes.

Consultations

It is strongly recommended that an ophthalmologist and a trained leprologist, if available, be included in the treatment of Hansen disease with ocular manifestations.

-

Classification of Hansen disease after Paul Fasal, MD.

-

Skin biopsy showing Mycobacterium leprae after Fite-Faraco staining.

-

Anterior uveitis in Hansen disease.

-

Hansen disease skin biopsy foam cells.

-

Hansen disease skin biopsy tuberculoid.

-

Corneal scraping showing acid-fast bacilli in Hansen disease.

-

Anterior chamber tap showing acid-fast bacilli in Hansen disease.

-

Hansen disease. Tuberculoid hand.

-

Hansen disease. Lucio phenomenon.

-

Ear nodules of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Facial nodules of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Lagophthalmos in a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Tuberculoid leg ulcer and biopsy site arm of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Claw hands of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Claw hands of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Claw hands of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Lagophthalmos seventh nerve of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Hansen disease. Corneal scar seventh nerve exposure.

-

Hansen disease. Facial nodule and erythema nodosum leprosum.

-

Corneal neovascularization iris pearls of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Avascular keratitis of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Corneal neovascularization of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Hansen disease. Corneal sensitivity determination with nylon monofilament.

-

Beaded corneal nerve in Hansen disease.

-

Iris pearls and avascular keratitis in Hansen disease.

-

Temporal thin eyebrows of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Cosmetic cover thin eyebrows of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Thin eyebrows of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Cataracts glaucoma synechia of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Retinal scar and uveal effusion in Hansen disease.

-

Retinal pearl in a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Nodular episcleritis of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Episcleritis of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Plasmoid (plastic) iridocyclitis of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

Purple skin from clofazimine of a patient with Hansen disease.

-

A 6-year-old boy with Hansen disease.