Overview

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite of the Apicomplexa phylum that can infect any mammal and bird on Earth. This versatility accouts for its worldwide geographic distribution. T gondii exists in three different forms: tachyzoites (also known as trophozoites or endozoites), bradyzoites (also known as cystozoites), and sporozoites (tissue cysts). The presence of tachyzoites indicates an active infection with rapid replication. The bradyzoites are the latent or dormant form of T gondii found in tissue cysts. The sporozoites represent dormant forms of highly infectious organisms found in the environment. [1, 2]

It has a sexual life cycle that occurs only in the definite feline host and an asexual cycle that occurs in the intermediate avian or mammalian host. In felines, ingestion of any of the three forms of T gondii causes invasion of the epithelial cells of the small intestine. [1]

Up to a third of the world's population may have been exposed to Toxoplasma gondii; however, most individuals will remain asymptomatic. Ocular infection gives rise to a spectrum of disease. [3] Ocular toxoplasmosis is a leading cause of posterior uveitis. [4]

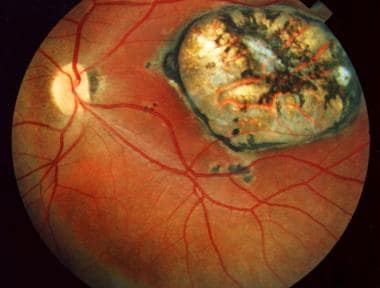

Acute macular retinitis associated with primary acquired toxoplasmosis, requiring immediate systemic therapy.

Acute macular retinitis associated with primary acquired toxoplasmosis, requiring immediate systemic therapy.

Pathogenesis

Patients become infected with toxoplamosis by 3 main routes: 1) Eating contaminated undercooked meat containing tissue cysts; 2) Consuming contaminated food or water with oocysts; and 3) Transplacental transmission of tachyzoites to the fetus during primary maternal infection. [5] Given these routes, one of the main sites where the parasite gains a foothold in the human body is the small intestine. From there, the parasite is carried by the bloodstream and the lymphatics. [6] The main point of entry of the parasite into the posterior segment of the eye is the retinal circulation. Rarely, it may gain access through the choroidal circulation as evidenced by the cases of punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis where the RPE and the outer retina are selectively affected. [7]

A recent mouse model of T gondii infection revealed that ferroptosis may be involved in the infection of photoreceptors during ocular toxoplasmosis. [8]

Congenital Versus Acquired Ocular Toxoplasmosis

Early studies proposed that most cases of ocular toxoplasmosis were secondary to congenital infection and that they tended to occur during the chronic phase of infection. Because reports showed that up to 75% of patients with congenital toxoplasmosis had chorioretinal scars at birth, most cases of intraocular toxoplasmosis were believed to be secondary to reactivation of a congenital infection. In contrast, ocular lesions in patients who acquired toxoplasmosis after birth were not found to be common.

The most common finding in congenital toxoplasmosis is the ophthalmologic manifestation retinochoroiditis, which has a predilection for the posterior pole. It is seen in 75-80% of cases and is bilateral in 85% of cases. [9, 10] In acquired toxoplasmosis, the ocular form of the disease occurs much less frequently. Previously, only 1-3% of patients with acquired infection were believed to develop ocular toxoplasmosis; however, serologic studies suggest that ocular toxoplasmosis is more commonly associated with acquired infection than was previously believed.

Later studies demonstrated the importance of acquired infection in the pathogenesis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Brazilian studies showed that only 1% of young children with toxoplasmosis had ocular lesions, whereas 21% of persons older than 13 years had ocular lesions. [11] Moreover, in a Canadian epidemic of toxoplasmosis, up to 21% of persons who were affected developed ocular lesions. [12] Serologic studies suggest that ocular toxoplasmosis is more commonly associated with acquired infection than previously believed. [13, 14, 15, 16] Typically, toxoplasmosis has been associated with the ingestion of undercooked meat contaminated with tissue cysts of Toxoplasma gondii. [17] More recently, it has been recognized that water contaminated with oocysts is an important source of infection. [18]

Toxoplasmosis in the immunocompromised host

Only 1-2% of patients with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are affected with ocular toxoplasmosis. [19, 20] Elderly patients who acquire toxoplasmosis are at a risk of developing a severe retinochoroiditis, presumably secondary to the waning of cellular immune function that occurs with aging. Local immunosuppression has been associated with intraocular toxoplasmosis. [21, 22]

Course of Ocular Toxoplasmosis

The hallmark of ocular toxoplasmosis is a necrotizing retinochoroiditis, which may be primary or recurrent. In primary ocular toxoplasmosis, a unilateral focus of necrotizing retinitis is present at the posterior pole in more than 50% of cases. The area of necrosis usually involves the inner layers of the retina and is described as a whitish, fluffy lesion surrounded by retinal edema. The retina is the primary site for the multiplying parasites, whereas the choroid and the sclera may be the sites of contiguous inflammation. [23, 24, 25]

When the disease involves the optic nerve, the typical manifestation is optic neuritis or papillitis associated with edema, often called Jensen disease.

The sheath of the optic nerve may serve as a conduit for the direct spread of Toxoplasma organisms into the optic nerve from an adjacent cerebral infection. This also results in optic neuritis or papillitis.

Punctate outer toxoplasmosis has been described in Japanese and American literature. This form of the disease is unique in that the classic large, atrophic, posterior lesions are not seen.

Inflammatory cells are seen in the vitreous overlying the retinochoroidal or papillary lesion. In many cases, the inflammatory reaction is severe, and the details of the fundus are not visible. This appearance has been termed a "headlight in the fog." Posterior vitreous detachment commonly is seen, and patients may develop precipitates of inflammatory cells on the posterior vitreous face, referred to as vitreous precipitates. Thick, vitreous strands and membranes may be present and may require vitrectomy.

Toxoplasma antigens are responsible for a hypersensitivity reaction that may result in retinal vasculitis and granulomatous or nongranulomatous anterior uveitis.

Posterior synechiae may complicate the course of anterior uveitis, and keratic precipitates (KP) may be seen. The KP may appear in the classic Arlt distribution in milder, nongranulomatous configurations and granulomatous morphology. In addition, some patients present with the stellate KP pattern, characterized by a diffuse, homogeneous distribution pattern and a stellate, fibrillar KP morphology.

As the lesion heals, it appears as a punched-out scar, revealing white underlying sclera. This results from extensive retinal and choroidal necrosis surrounded by variable pigment proliferation.

With reactivation of live tissue cysts located at the border of the scars (recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis), the areas of newly active necrotizing retinitis usually are adjacent to old scars (so-called satellite lesions). In some patients, multiple grayish white dots at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) appear. No associated vitreous reaction occurs with this manifestation.

As in other inflammatory conditions, macular edema may be seen. Rarely, ocular inflammation without the necrotizing retinochoroiditis can occur in patients with acquired toxoplasmosis. These patients present with retinal vasculitis, vitreitis, and anterior uveitis. Later, they may develop retinochoroidal scars that suggest that the inflammatory reaction was secondary to Toxoplasma gondii.

Rarely, retinal and optic nerve neovascularization may follow. [26, 27] The neovascularization usually regresses with resolution of the inflammation. The exact etiology of neovascularization of the optic nerve and the retina is not well understood. Retinal ischemia associated with severe retinal vasculitis may predispose to neovascularization of the retina. On the other hand, inflammatory reactions alone may cause neovascularization of the retina.

Elevated intraocular pressure at initial examination reflects the severity of inflammation in ocular toxoplasmosis. [28]

Associated serous retinal detachments appear to be more common than previously believed. They usually resolve after 6 weeks. [29]

Workup

Fundus autofluorescence fluorescein angiography

Fluorescein angiography (FA) of active lesions shows hypofluorescence during the early phase of the study, followed by progressive hyperfluorescence secondary to leakage.

Indocyanine green

Indocyanine green (ICG) of active lesions mostly is hypofluorescent. ICG has imaged hypofluorescent satellite lesions that are not imaged by FA and are not seen during clinical examination. Acute choroidal ischemia may be seen in conjunction with serous retinal detachment. [29] Multimodal imaging in patients with active ocular toxoplasmosis reveals that 50% of patients had hyperautofluorescent retinal spots around the active toxoplasmosis foci. These hyperautofluorescent spots co-localized with the satellite dark dots seen on ICGA suggesting that the ICGA hypofluorescent lesions are inflammatory lesions at the level of the RPE and / or outer retina. [30]

Optical coherence tomography scanning

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scanning is helpful in identifying potential complications, including epiretinal membrane, cystoid macular edema, vitreoretinal traction, choroidal neovascularization, and serous retinal detachments. [29] Active toxoplasmic lesions have been imaged with OCT and have been characterized by a highly reflective intraretinal area corresponding with the area of retinitis that also shadows the underlying choroid. The posterior hyaloid is thickened and detached over the lesion. [31]

Fundus autofluorescence

The active acute toxoplasmic retinal lesion appears hypo-autofluorescent. In about 50% of patients transient hyper-autofluorescent spots appear in the vicinity of the acute toxoplasmic foci. These are associated with disruption of the ellipsoid and inner digitation zones and tend to resolve in about a month. OCT-A did not reveal choriocapillaris ischemia in this area. [30]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is indicated in the presence of ocular media opacities, especially vitreous opacities. The most common findings include intravitreal punctiform echoes, thickening of the posterior hyaloid, partial or total posterior vitreous detachment, and focal retinochoroidal thickening.

Vitreous sample or aqueous sample

Atypical cases may require either a vitreous sample or an aqueous sample. Antitoxoplasma immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgA antibodies may be detected in either an aqueous sample or a vitreous sample. A coefficient is calculated by comparing the concentration of anti-Toxoplasma antibody in the eye and the serum, divided by the concentration of gamma globulin in the aqueous to that in the serum. A coefficient of 8 or higher is consistent with active ocular toxoplasmosis.

Despite the precision of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), aqueous humor samples only yielded a 30% positive result for T gondii DNA. [32]

A small study reported that eyes with toxoplasma chorioretinitis had reduced intravitreal iron levels. This may serve to diiferentiate these eyes from eyes with acute retinal necrosis from herpetic viruses. [8]

Histologic findings

Histopathology is the criterion standard for diagnosis. Tissue diagnosis is impractical and rarely used clinically. A retinal biopsy infrequently may be required to elucidate the diagnosis in a highly atypical case. In histologic sections, the tachyzoites appear ovoid or crescent shaped. They measure 6-7 µm in length and 2-3 µm in width.

The tachyzoites stain well with Giemsa stain and Wright stain. Giemsa-stained smears reveal a bluish cytoplasm and a reddish spherical or ovoid nucleus. In the cyst forms, the wall is eosinophilic, argyrophilic, and weakly periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive. The cyst may contain anywhere from 50-3000 bradyzoites. The bradyzoites within the cyst are strongly PAS positive. They form intracellularly within vacuoles. The surrounding membrane is produced by the parasite.

An intense inflammatory reaction is present in the retina, the overlying vitreous, and the underlying choroid. The choroid adjacent to the retinal foci usually shows a granulomatous inflammation. The retina is partially necrotic, with a well-defined border between necrotic and unaffected retina. After healing, the retina in the area of infection is destroyed, and chorioretinal adhesions are present.

Staging

A zone 1 area is defined where there is a high risk of sustaining permanent visual loss. This area is defined as 2 disk diameters from the fovea (which happens to be an area enclosed by the major temporal arcades) or 1500 µm from the margins of the optic disc. If toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis occurs within zone 1, aggressive treatment should be instituted immediately.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmacologic treatment is the mainstay of treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis.

In the case of ocular toxoplasmosis, several therapeutic regimens have been recommended. Triple drug therapy refers to pyrimethamine (loading dose of 75-100 mg during the first day, followed by 25-50 mg on subsequent days), sulfadiazine (loading dose of 2-4 g during the first 24 h followed by 1 g qid), and prednisone. Quadruple therapy refers to pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, clindamycin, and prednisone (1 mg/kg of weight). Pyrimethamine should be combined with folinic acid to avoid hematologic complications. The duration of treatment varies depending on the patient's response but usually lasts for 4-6 weeks.

A combination of 60 mg of trimethoprim and 160 mg of sulfamethoxazole given every 3 days was used as prophylaxis against recurrence of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. After a follow-up of 20 months, the recurrences were seen in only 6.6% of patients taking the combination, in comparison with 23.6% of patients taking the placebo. [33]

During pregnancy, spiramycin and sulfadiazine can be used in the first trimester. Throughout the second trimester, spiramycin, sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and folinic acid are recommended. Spiramycin, pyrimethamine, and folinic acid may be used during the third trimester. [34]

Topical corticosteroids are used depending on the anterior chamber reaction. Depot steroid therapy is absolutely contraindicated in the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis. The high-dose medication in close proximity to ocular tissues apparently overwhelms the host's immune response, leading to rampant necrosis and the potential for a blind, phthisical globe. Systemic corticosteroids are used as an adjunct to minimize collateral damage from the inflammatory response.

Topical cycloplegic agents are used depending on the anterior chamber reaction and the degree of pain. They also are used to prevent formation of posterior synechiae.

Antitoxoplasmic agents

Antitoxoplasmic agents include the following:

-

Sulfadiazine

-

Clindamycin - Intravitreal clindamycin (0.1 mg/0.1 mL) was reported to be beneficial as salvage therapy in eyes that did not respond to conventional oral treatment [35]

-

Pyrimethamine

-

Atovaquone - 750 mg qid; has been used as second-line therapy for toxoplasmosis

-

Azithromycin - 250 mg/d or 500 mg every other day in combination with pyrimethamine 100 mg on the first day followed by 50 mg/d on subsequent days; has also been used as an alternative

A randomized clinical trial demonstrated a comparable effect of intravitreal clindamycin (1 mg) plus intravitreal dexamethasone (400 µg) with the triple therapy of sulfadiazine (loading dose of 4 g daily for 2 d followed by 500 mg qid), pyrimethamine (loading dose of 75 mg for 2 d followed by 25 mg daily), folinic acid (5 mg qd), and prednisolone (1 mg/kg starting on the third day of therapy) for 6 weeks in the treatment of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. [36]

In the study, the reduction in lesion size, reduction in vitreous inflammation, and improvement in visual acuity were similar in both groups. Intravitreal clindamycin plus dexamethasone may be an acceptable and effective alternative in selected patients with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis and may offer patients greater convenience, a safer systemic side-effect profile, greater availability, and fewer follow-up visits and hematologic evaluations.

A combination of trimethoprim (60 mg) and sulfamethoxazole (160 mg) was shown to cause a 59% reduction in lesion size, as compared with a 61% reduction in eyes treated with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine. [37]

In select cases, intravitreal therapy with clindamycin (1 mg) and dexamethasone (400 µg) may be indicated. [36] Another alternative involves an intravitreal injection of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole combined with intravitreal dexamethasone. [38]

In patients with a high risk for recurrent attacks and lesions located in the macula or near the optic nerve, prophylaxis with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole has been advocated. [39]

Surgical Treatment

Photocoagulation, cryotherapy, and vitrectomy

Caution must be exercised if photocoagulation or cryotherapy is being considered in the treatment of intraocular toxoplasmosis. Intraretinal hemorrhages, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment have been reported as complications of such treatment. Tissue cysts can exist in a normal-appearing retina.

Pars plana vitrectomy may be indicated in cases of retinal detachment secondary to vitreous traction or in cases where vitreous opacities persist. Vitreoretinal consultation is desired if pars plana vitrectomy is being considered.

-

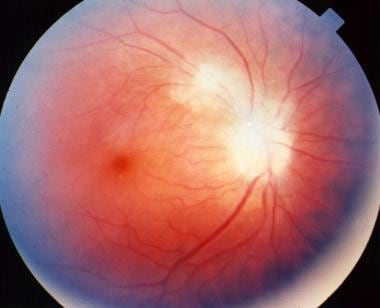

Macular scar secondary to congenital toxoplasmosis. Visual acuity of the patient is 20/400.

-

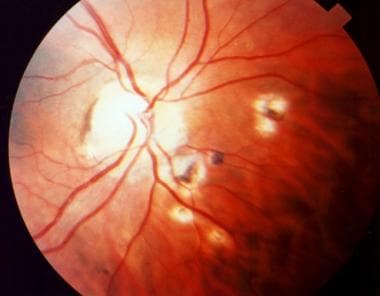

Papillitis secondary to toxoplasmosis, necessitating immediate systemic therapy.

-

Acute macular retinitis associated with primary acquired toxoplasmosis, requiring immediate systemic therapy.

-

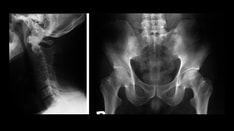

Peripapillary scars secondary to toxoplasmosis.

-

Peripapillary scars secondary to toxoplasmosis.

-

Inactive chorioretinal scar secondary to toxoplasmosis.