Overview

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease of the neuromuscular junction in which circulating antibodies cause fluctuant skeletal muscle weakness. [1, 2] Ninety percent of patients with myasthenia gravis develop ophthalmologic manifestations of the disease, a disorder of neuromuscular transmission characterized by weakness and fatigability of skeletal muscles. [1, 3] Variability in the muscle weakness is a hallmark of myasthenia. The pathophysiology of adult MG is a reduced number of acetylcholine receptors (AChR) at the postsynaptic muscle membrane due to circulating anti-AChR antibodies [4] or, less commonly, to antibodies to muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (anti-MuSK), LRP4, and agrin. [5, 6]

MG is differentiated into two major clinical forms: ocular MG, in which the patient has predominantly ocular symptoms, and generalized MG, in which the patient develops generalized proximal weakness. [7] One study found that, over a mean follow-up period of 17 years, approximately 15-17% of patients with MG had strictly ocular symptoms. [2]

Some evidence shows that steroids or azathioprine might prevent the conversion to generalized MG in 75% of patients with ocular MG. [8]

Bever and coworkers reported that 82% of patients who later developed generalized weakness did so in the first 2 years after diagnosis. [9] Hence, patients who keep having strictly ocular symptoms for 3 or more years are unlikely to revert to the generalized aspect of the disease. Nonetheless, the definition of ocular MG proposed by consensus is based on any ocular muscle weakness attributed to MG at a specified point in time and not dependent on the duration of disease. [10]

Patient History

History

The clinical hallmark of myasthenia is variability in the symptoms and signs of muscle weakness. Patients may notice less impairment immediately upon awakening or after resting. Systemic myasthenia can manifest as dysphagia, dyspnea, dysphonia, and proximal muscle weakness (eg, difficulty climbing stairs or getting out of chairs).

A thorough medication history is required since medications can cause or exacerbate myasthenia gravis. The risk of medication-induced myasthenia varies, but medications that should be avoided whenever possible include D-penicillamine; interferon; antibiotics including telithromycin, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and azithromycin; beta blockers; calcium channel blockers; magnesium; procainamide; quinine; phenytoin; and, occasionally, statins. [11]

Ophthalmic symptoms

Among patients with myasthenia gravis (MG), 75% initially complain of ocular disturbance, mainly ptosis and diplopia. Eventually, 90% of patients with MG develop ocular symptoms. About 50% of patients present solely with ocular symptoms, and about 50-60% of these patients will progress to develop generalized disease. Ptosis may be unilateral or bilateral or may alternate sides.

Nonophthalmic symptoms

Oropharyngeal muscle disturbances come second in presentation, with 15% of patients first experiencing difficulty in swallowing, talking, and chewing. [12] Limb and trunk weakness is the initial complaint of 10% of patients, and 85% of patients with MG develop a generalized weakness also affecting the limb muscles.

MG can involve the respiratory muscles and lead to respiratory failure. This can sometimes be the first presentation of the disease. Qureshi et al showed that out of 51 patients with MG and respiratory failure, 7 (14%) had no previous diagnosis of MG. [13]

Physical Examination

Ptosis

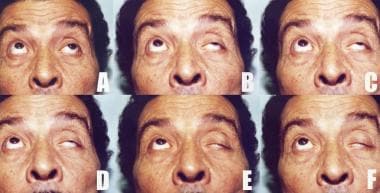

Ptosis may be unilateral or bilateral; it may be elicited with sustained upward gaze, as shown in the image below, or on repeated eyelid closure. During slit-lamp examination, patients with myasthenia may show a subtle rise and fall in the lid height. Photodocumentation on sustained upgaze or in different positions of gaze may aid in the identification of varying ptosis. [14]

Increasing left ptosis developing upon sustained upward gaze in a patient with myasthenia gravis (A through F). Note the limited elevation of the left eye denoting superior rectus palsy (A). A initially, C after around 20 seconds, F after 1 minute.

Increasing left ptosis developing upon sustained upward gaze in a patient with myasthenia gravis (A through F). Note the limited elevation of the left eye denoting superior rectus palsy (A). A initially, C after around 20 seconds, F after 1 minute.

In cases of unilateral ptosis, the contralateral lid may assume a ptotic position upon occluding the eye with the ptosis or lifting the ptotic lid with a finger (Herring phenomenon).

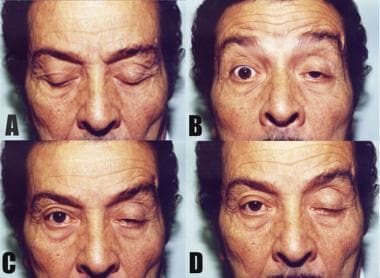

The lid twitch sign described by Cogan can be elicited by having the patient change gaze from the downward position to the primary position. [15] The lid will be seen to overshoot in a twitch before gaining its initial ptotic position; this is shown in the image below. A study, however, questioned the validity of such a sign, as its sensitivity and specificity were shown to be relatively low. [16]

Cogan sign. The patient changes gaze from the downward position (A) to the primary position (B). Both lids are seen to overshoot in a twitch (B) before gaining their initial ptotic position (D). In this case, the Cogan sign is seen more obviously on the right, whereas the left lid is more ptotic.

Cogan sign. The patient changes gaze from the downward position (A) to the primary position (B). Both lids are seen to overshoot in a twitch (B) before gaining their initial ptotic position (D). In this case, the Cogan sign is seen more obviously on the right, whereas the left lid is more ptotic.

Extraocular muscle involvement

Myasthenia gravis can mimic almost any painless, pupil-sparing ocular motility disorder, including internuclear ophthalmoplegia. The motility deficit may not follow any particular pattern, but the deviation more often is incomitant than comitant. Forced ductions should be normal.

Orbicularis involvement

Orbicularis involvement consistently is present when ocular symptoms are reported. Weakness in forceful closure of the eyes against resistance is present. With prolonged lid closure, the lids may spontaneously open (peek sign).

Pupils and ciliary muscles

Traditionally, pupils and ciliary muscles were believed not to be involved, although studies such as a case analysis by Cooper and coworkers suggest the contrary. [17]

Sleep/rest test with local cooling

Prism measurements and margin reflex distance-1 should be documented in patients who have diplopia or ptosis with a facial photo on a cell phone camera.

The patient is asked to lie supine with eyes closed in an examination chair for up to 20 minutes. A supplemental cool compress or small amount of ice in an examining glove is placed over the closed lids, as tolerated. Upon re-examination with the patient sitting up, the lid height and alignment often are improved in patients with myasthenia.

Workup

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is recommended for cases of suspected ocular myasthenia to exclude intracerebral pathology. Chest CT scanning is used to exclude thymoma.

Acetylcholine receptor antibody blood testing

Acetylcholine receptor antibody blood testing is specific but not sensitive for myasthenia gravis. Acetylcholine receptor antibody test results are more likely to be positive in patients with systemic myasthenia than in patients with ocular myasthenia. "Seronegative" myasthenia gravis with anti-muscle specific kinase (MuSK) antibodies, presenting as ocular myasthenia, is uncommon but has been described. [18] Low‐density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 4 (LRP4) or agrin antibodies have been reported in a patient presenting with binocular diplopia. [19]

Edrophonium testing

Edrophonium (Tensilon) is not available in North America, so rest or sleep tests more commonly are used.

Single-fiber electromyography

If the diagnosis of ocular myasthenia remains in question, some neurologists can perform single-fiber electromyography of the eyelids.

Thyroid function testing

Thyroid function tests may be performed, as the patient may have accompanying autoimmune thyroid disease.

Differential Diagnoses

Differential diagnoses may include the following [20] :

-

Oculomotor nerve palsy, partial or complete (pupil sparing)

-

Trochlear nerve palsy

-

Abducens nerve palsy

-

Skew deviation

-

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

-

Gaze palsy

The mitochondrial cytopathies may mimic the outward appearance of ocular myasthenia. Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) may manifest as ptosis and decreased eye movements. CPEO has little to no diurnal variation, and patients usually do not have diplopia (although the author has encountered many patients with CPEO and exotropia). Patients with oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy have ptosis and dysphagia.

Lambert Eaton syndrome (LES) is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that usually is associated with small cell lung cancer. LES can mimic some of the features of myasthenia gravis, but less diplopia usually occurs. The presence of autoantibodies to the presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels is a feature of LES. [21]

The overlap of myasthenia gravis and the bulbar variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome (Miller Fisher syndrome) has been described. [22] Miller Fisher syndrome may show anti–ganglioside complex antibodies.

A case of myasthenia gravis imitating pituitary apoplexy has been described. [23]

Treatment of Ocular Myasthenia

The 4 main treatment options for myasthenia gravis (MG) include the following:

-

Symptomatic treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitor therapy (eg, pyridostigmine)

-

Long-term immunomodulation (with glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants)

-

Rapid immunomodulation (eg, plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin)

-

Surgery (thymectomy, ptosis, or strabismus surgery)

An international consensus guideline for the management of myasthenia gravis was published in 2016. [10, 24] Many clinicians initiate cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, pyridostigmine); if there is no effect, they start immunosuppressants, most commonly systemic steroids. Patients with myasthenia who are prescribed systemic steroids may paradoxically worsen during the first few weeks of treatment. Other immunosuppressants include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and tacrolimus, as well as rituximab for anti-MuSK disease. [10] Plasmapheresis can be considered in severe cases of myasthenia. Antigen-specific immunotherapeutic vaccines are being investigated in animal models. [36] Stem cell therapy has been proposed. [25] Medical treatment is administered in conjunction with a neurologist or internist. Investigational medications include complement C5 inhibitors, neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) inhibitors, anti-CD19 monoclonal antibodies, interleukin 6 inhibition, and Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors.

Medical treatment of bothersome ptosis includes taping of the lids or ptosis crutch glasses. Binocular diplopia does not occur in patients with marked unilateral ptosis. Occasional patients with myasthenia gravis who have binocular diplopia benefit from prism. If there is too much variability in the misalignment, patching or a translucent occluder may be more appropriate. Surgery normally is not performed for ptosis or strabismus due to myasthenia (see below). The value of thymectomy for non-thymomatous ocular MG requires further study. [26, 27]

Strabismus surgery

Strabismus surgery usually is not performed because of variability in the alignment. However, if myasthenia medications have been optimized and the misalignment is stable for more than 12 months, strabismus surgery may be considered if patients desire. Successful muscle surgery for selected patients with a stable course of MG and persistent diplopia has been reported. [28, 29, 30]

Blepharoptosis surgery

Ptosis surgery for myasthenia is complicated by variable lid height, possible corneal exposure due to concomitant orbicularis weakness, and the possible unmasking of diplopia in patients with unilateral ptosis. Ptosis surgery in patients with stable ptosis that has failed to respond to medical therapy for MG has been described. The surgical technique can include external levator tuck/advancement, frontalis suspension sling, or tarsomyectomy. [31, 32, 33] A readily reversible ptosis repair technique is recommended for patients with myasthenia. Patients with myasthenia should understand the increased risk for corneal exposure, dry eye, revision surgery, and eyelid asymmetry.

Consultations and follow-up

Consult neurologists after diagnosing patients with ocular MG. Treatment is initiated best by them rather than by the ophthalmologist. Follow-up care of the patient with MG is conducted mainly by the neurologist, who will orchestrate the treatment. The ophthalmologist is consulted accordingly.

Patients who require strabismus or ptosis surgery should undergo preoperative anesthesia consultation.

Pediatric Myasthenia Gravis

Pediatric myasthenia gravis can be classified as neonatal or juvenile. [34]

Neonatal MG is characterized by a transfer of maternal acetylcholine receptor antibodies to the infant and is transient with a good prognosis.

Juvenile ocular MG is autoimmune ocular MG that presents before age 19 years. It carries a better prognosis for spontaneous remission than does adult disease. Children with only ocular MG initially can be treated with pyridostigmine. [10] Juvenile MG may be difficult to distinguish from congenital myasthenic syndromes (structural alterations to the neuromuscular junction).

-

Increasing left ptosis developing upon sustained upward gaze in a patient with myasthenia gravis (A through F). Note the limited elevation of the left eye denoting superior rectus palsy (A). A initially, C after around 20 seconds, F after 1 minute.

-

Cogan sign. The patient changes gaze from the downward position (A) to the primary position (B). Both lids are seen to overshoot in a twitch (B) before gaining their initial ptotic position (D). In this case, the Cogan sign is seen more obviously on the right, whereas the left lid is more ptotic.

-

CT scan of chest/mediastinum showing a thymoma in a patient with myasthenia gravis.

-

Repetitive nerve stimulation at a frequency of 2 Hz showing an increasing decrement in the amplitude of the compound muscle action potential up to the fourth response (42% amplitude loss), after which it stabilizes.

-

Single fiber electromyography showing the "jitter" phenomenon (second action potential wave group).