Overview

Since the EEG is a test of cerebral function, diffuse (generalized) abnormal patterns are by definition indicative of diffuse brain dysfunction (ie, diffuse encephalopathy). [1, 2, 3, 4]

This article discusses the following EEG encephalopathic findings:

-

Generalized slowing: This is the most common finding in diffuse encephalopathies. Focal (localized) slow activity reflects focal dysfunction, not diffuse dysfunction (ie, encephalopathy).

-

More severe patterns: These patterns are generally considered the next level of severity beyond generalized slowing. They include periodic patterns (such as burst-suppression), background suppression, and electrocerebral inactivity (ECI).

-

Less common patterns: These include alpha coma, beta coma, spindle coma, and triphasic waves.

Generalized Slowing

Waveform Description

Generalized slowing can be divided in a clinically useful way into 3 patterns: background slowing, intermittent slowing, and generalized slowing.

-

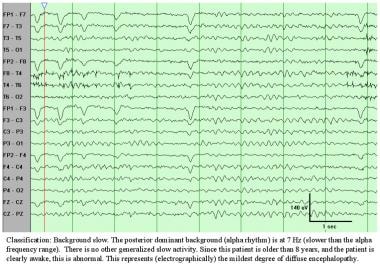

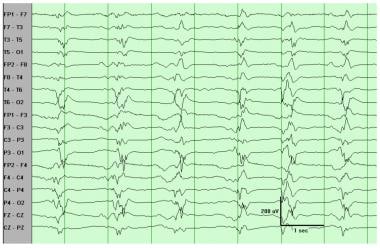

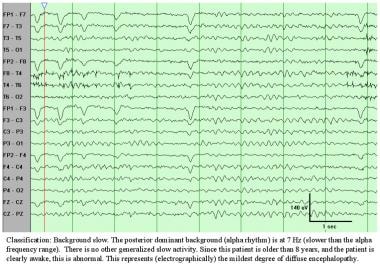

Background slowing: A posterior dominant and reactive background is present, but its frequency is too slow for the patient's age. The lower limit of normal generally is considered to be 8 Hz beginning at age 8 years. A guideline to remember the lower limits of normal is as follows: 5-6-7-8 Hz at ages 1-3-5-8 years, respectively.

Background slowing. The posterior dominant background (alpha rhythm) is at 7 Hz, slower than the alpha frequency range. No other generalized slow activity is present. Since this patient is older than 8 years, and is clearly awake, this is abnormal. This represents (electrographically) the mildest degree of diffuse encephalopathy.

Background slowing. The posterior dominant background (alpha rhythm) is at 7 Hz, slower than the alpha frequency range. No other generalized slow activity is present. Since this patient is older than 8 years, and is clearly awake, this is abnormal. This represents (electrographically) the mildest degree of diffuse encephalopathy.

-

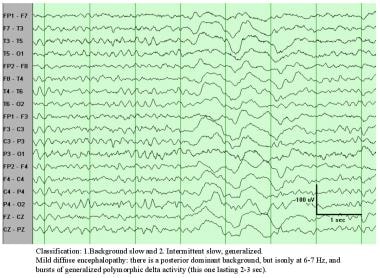

Intermittent slowing: This involves bursts of generalized slowing, usually polymorphic delta. More rarely, the intermittent bursts are in the theta frequency range, and occasionally they can be rhythmic rather than polymorphic. When rhythmic, this pattern sometimes is referred to as frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA). The EEG is still reactive to external stimulation and, for example, may have evidence of state changes such as drowsiness or sleep. A posterior dominant background is usually present, and it may be normal or slow in frequency.

-

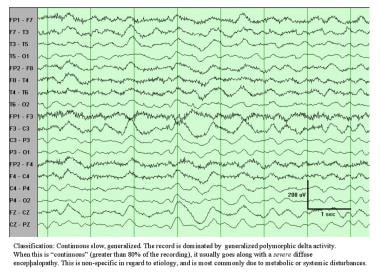

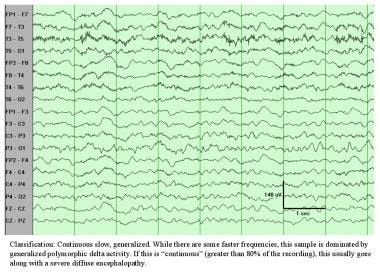

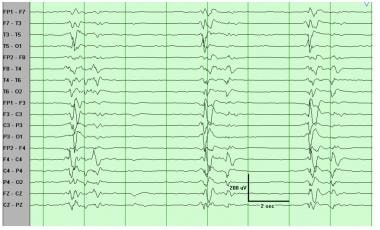

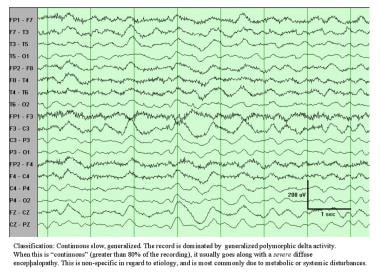

Continuous slowing: Polymorphic delta activity (PDA) occupies more than 80% of the record. This is usually unreactive, and a posterior dominant background is usually absent.

Continuous slowing, generalized. The record is dominated by generalized polymorphic delta activity. When this is "continuous" (greater than 80% of the recording), it usually goes along with a severe diffuse encephalopathy. This is nonspecific in regard to etiology and most commonly is due to metabolic or systemic disturbances.

Continuous slowing, generalized. The record is dominated by generalized polymorphic delta activity. When this is "continuous" (greater than 80% of the recording), it usually goes along with a severe diffuse encephalopathy. This is nonspecific in regard to etiology and most commonly is due to metabolic or systemic disturbances.

Clinical Correlation

Essentially, the 3 levels of slowing described above represent 3 degrees of severity (ie, mild, moderate, and severe) of diffuse encephalopathy. As usual, this is completely nonspecific as to etiology and most commonly is observed in metabolic and toxic (including medication-induced) encephalopathies. It also can be observed in diffuse structural or degenerative processes. However, most slowly progressive neurodegenerative diseases (eg, dementias of the Alzheimer type) go along with a normal EEG until the very late stages.

More Severe EEG Patterns

Waveform Description

See the list below:

-

Periodic patterns: Discharges occur at regular intervals (ie, periodicity). The discharges are typically complex and multiphasic and are often epileptiform in morphology. [5, 6] Thus, they are like periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges (PLEDs), except instead of being lateralized, they are generalized. They are sometimes referred to as generalized periodic epileptiform discharges (GPEDs). Their periodicity rather than their morphology sets them apart as a unique and clinically useful entity (as is true for PLEDs). By contrast, the term bi-PLEDs usually refers to periodic discharges that are bihemispheric but asynchronous (ie, independent).

-

Burst-suppression pattern: This subtype of periodic pattern consists of bursts of activity (mixture of sharp and slow waves) periodically interrupted by episodes of suppression (activity < 10 µV). Typically, the episodes of suppression are longer (typically 5-10 s) than the bursts of activity (typically 1-3 s).

-

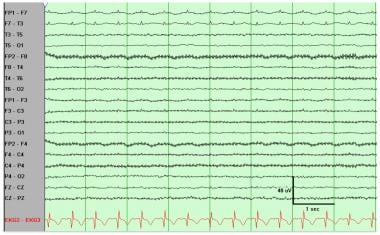

Background suppression: This is a "nearly flat" EEG, with very low voltage activity (< 10 µV) and no reactivity, but the activity is still too large to meet criteria for ECI.

-

Electrocerebral inactivity: ECI is defined by no activity greater than 2 µV; to support a diagnosis of brain death while avoiding "overcalling" brain death, ECI must be recorded according to strict guidelines. These requirements specify recording time, double interelectrode distances, testing reactivity, and the integrity of the system. [7] (See Generalized EEG Waveform Abnormalities for the ECI Guidelines of the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society.)

Clinical Correlation

As usual, these severe encephalopathic patterns are completely nonspecific as to etiology but represent extremely severe degrees of diffuse encephalopathy. Because sedative medications can cause or aggravate these abnormalities, careful interpretation is warranted when reading these patterns. These patterns are indicative of very severe brain dysfunction if sedative medications can be excluded with certainty as their cause. [8]

Periodic patterns, including burst-suppression patterns, are somewhat more common in anoxic injuries than in other systemic disturbances. Periodic patterns can be induced by high doses of sedatives such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or propofol. In fact, burst-suppression pattern is typically the goal and the method used to titrate doses of anesthetics for treatment of refractory status epilepticus.

In the appropriate clinical context, certain periodic patterns can suggest and support the diagnoses of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). Classically, the periodicity for CJD is approximately 1-2 seconds, whereas it is much longer in SSPE (approximately 4-10 s).

Rhythmicity or periodicity is one of the hallmarks of electrographic seizures; thus, periodic patterns quite often are observed in the context of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. [9] Often the decision whether to consider a periodic pattern ictal must rely on clinical information or the response to anticonvulsant treatment.

ECI is supportive of a clinical diagnosis of brain death. Remembering and emphasizing that brain death is a clinical diagnosis is important. Contrary to a common misconception, EEG is not required for the diagnosis of brain death and is considered only as a supportive test. [7]

Less Common EEG Patterns

Waveform Description

Unusual special patterns observed in comatose patients include alpha coma, beta coma, and spindle coma. [10, 11]

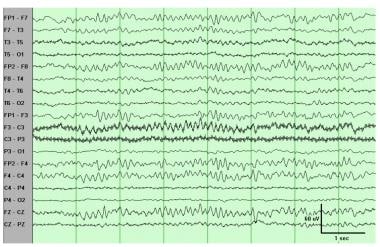

Alpha coma. Unlike a normal alpha rhythm, the alpha activity observed here is not posterior dominant, is continuous, and is nonreactive. If the entire record is present and the patient is known to be comatose, this qualifies as alpha coma.

Alpha coma. Unlike a normal alpha rhythm, the alpha activity observed here is not posterior dominant, is continuous, and is nonreactive. If the entire record is present and the patient is known to be comatose, this qualifies as alpha coma.

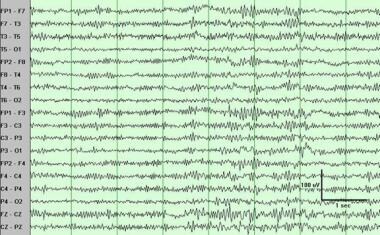

Beta coma. Prominent fast (beta) activity is noted at 15-22 Hz. To qualify as "excessive fast" activity, the pattern has to be the predominant frequency and excessive in amount (ie, nearly continuous and unreactive) and amplitude, ie, greater than the typical 30 microvolts of the normal beta activity. Note that this pattern could be seen in an awake patient, so that the term "beta coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

Beta coma. Prominent fast (beta) activity is noted at 15-22 Hz. To qualify as "excessive fast" activity, the pattern has to be the predominant frequency and excessive in amount (ie, nearly continuous and unreactive) and amplitude, ie, greater than the typical 30 microvolts of the normal beta activity. Note that this pattern could be seen in an awake patient, so that the term "beta coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

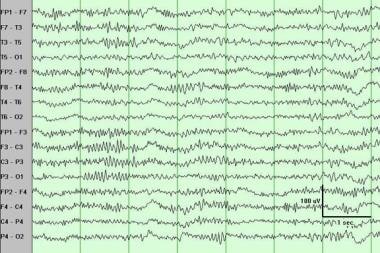

Spindle coma. Note the prominent spindlelike activity at 13-16 Hz. Typically, spindlelike activity associated with coma is even more continuous than shown here, and unreactive. The term "spindle coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

Spindle coma. Note the prominent spindlelike activity at 13-16 Hz. Typically, spindlelike activity associated with coma is even more continuous than shown here, and unreactive. The term "spindle coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

These patterns are characterized by electrical activity that morphologically resembles and sometimes appears nearly identical to normal waveforms (ie, alpha rhythm, beta activity, spindles).

To be classified as one of these patterns, the activity should be frankly excessive in amplitude or in spatial distribution (ie, widespread), appear in unusual spatial distribution, or appear excessive in amount (ie, near continuous). Although some investigators classify these patterns as abnormal even if the pattern is reactive, unreactive activity is preferred. The most important criterion is patient coma at the time of clinical recording.

Triphasic waves are frontally positive sharp transients, usually of greater than 70 microvolts amplitude (see image below). The positive phase is usually preceded and followed by a smaller negative waveform. As a rule, the first negative wave is of higher amplitude than the second. They are bilateral and occur in bursts of repetitive waves at 1-3 Hz. No reactivity is the rule, and often an anterior-posterior temporal lag can be observed. The largest deflection is usually frontal, and in ear referential montage the time lag is usually not present. The usual clinical correlate of triphasic waves is a metabolic or other diffuse encephalopathy. Thus, a triphasic morphology (while necessary) is not sufficient to classify a record as "triphasic waves."

Triphasic waves. Note the near continuous pattern of periodic triphasic waveforms, with a large frontal positivity (downgoing) preceded and followed by smaller negative deflections. The wave marked near the middle of the sample illustrates the classic anterior-posterior lag. This pattern is typically unreactive. Note that a triphasic morphology is necessary but not sufficient to classify a pattern as triphasic waves.

Triphasic waves. Note the near continuous pattern of periodic triphasic waveforms, with a large frontal positivity (downgoing) preceded and followed by smaller negative deflections. The wave marked near the middle of the sample illustrates the classic anterior-posterior lag. This pattern is typically unreactive. Note that a triphasic morphology is necessary but not sufficient to classify a pattern as triphasic waves.

Clinical Correlation

Alpha coma, beta coma, and spindle coma are infrequent. They are, like all the encephalopathic patterns, nonspecific in regard to etiology, although anoxia often is associated with alpha coma and drugs with beta coma. They are generally indicative of a severe degree of encephalopathy. Reactivity is a good prognostic factor. In fact, some investigators, including the author, do not classify a record as alpha or spindle coma if it is reactive.

Triphasic waves classically are associated with hepatic encephalopathy. However, they are not specific and can be observed in uremic encephalopathy and even other types of metabolic derangements. Many other patterns can have a triphasic morphology. Like periodic patterns, triphasic waves quite often are observed in the context of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Often the decision whether to consider triphasic waves ictal must rely on the clinical information or the response to anticonvulsant treatment.

Patient Education

For excellent patient education resources, see eMedicineHealth's patient education article Electroencephalography (EEG)

-

Background slowing. The posterior dominant background (alpha rhythm) is at 7 Hz, slower than the alpha frequency range. No other generalized slow activity is present. Since this patient is older than 8 years, and is clearly awake, this is abnormal. This represents (electrographically) the mildest degree of diffuse encephalopathy.

-

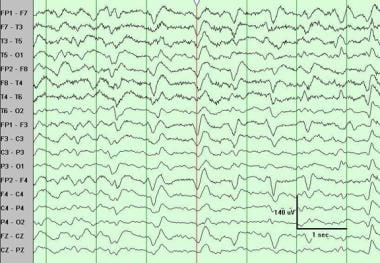

(1) Background slowing and (2) intermittent slowing, generalized. Mild diffuse encephalopathy; a posterior dominant background is present, but it is only at 6-7 Hz, and bursts of generalized polymorphic delta activity (this one lasting 2-3 s) are present.

-

Continuous slowing, generalized. The record is dominated by generalized polymorphic delta activity. When this is "continuous" (greater than 80% of the recording), it usually goes along with a severe diffuse encephalopathy. This is nonspecific in regard to etiology and most commonly is due to metabolic or systemic disturbances.

-

Continuous slowing, generalized. While some faster frequencies are present, this sample is dominated by generalized polymorphic delta activity. If this is "continuous" (greater than 80% of the recording), this usually goes along with a severe diffuse encephalopathy.

-

Classification: periodic pattern, generalized. The periodicity here is approximately 1 second.

-

Classification: burst-suppression. Note that this is a 15-second segment, to show the periods of suppression (4-5 s) separated by the bursts. Suppression periods are characterized by activity less than 10 mV.

-

Classification: electrocerebral inactivity. The recording demonstrates no cerebral activity greater than 2 mV. Given the high sensitivity (2 mV/mm), a combination of ECG and 60-Hz artifact often is present, as observed here.

-

Alpha coma. Unlike a normal alpha rhythm, the alpha activity observed here is not posterior dominant, is continuous, and is nonreactive. If the entire record is present and the patient is known to be comatose, this qualifies as alpha coma.

-

Beta coma. Prominent fast (beta) activity is noted at 15-22 Hz. To qualify as "excessive fast" activity, the pattern has to be the predominant frequency and excessive in amount (ie, nearly continuous and unreactive) and amplitude, ie, greater than the typical 30 microvolts of the normal beta activity. Note that this pattern could be seen in an awake patient, so that the term "beta coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

-

Spindle coma. Note the prominent spindlelike activity at 13-16 Hz. Typically, spindlelike activity associated with coma is even more continuous than shown here, and unreactive. The term "spindle coma" is reserved for patients known to be comatose.

-

Triphasic waves. Note the near continuous pattern of periodic triphasic waveforms, with a large frontal positivity (downgoing) preceded and followed by smaller negative deflections. The wave marked near the middle of the sample illustrates the classic anterior-posterior lag. This pattern is typically unreactive. Note that a triphasic morphology is necessary but not sufficient to classify a pattern as triphasic waves.