Background

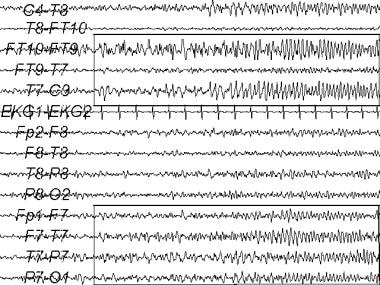

Many diseases can cause paroxysmal clinical events. The correct diagnosis of the paroxysmal event is necessary to provide correct treatment. If the event is an epileptic seizure, the seizure type and associated clinical, electroencephalographic (EEG) (see an example in the image below), and neuroimaging findings assist in determining the risk of seizure recurrence and the possible need to begin anticonvulsant therapy. Yet, the correct diagnosis is often missed.

Scheepers et al reported 49 patients with an incorrect diagnosis and 26 patients with an uncertain diagnosis among 214 patients with a diagnosis of epilepsy. [1] In addition, about 30% of patients seen at epilepsy centers for refractory seizures turn out to have been misdiagnosed and do not have seizures. [2]

An electroencephalogram (EEG) recording of a temporal lobe seizure. The ictal EEG pattern is shown in the rectangular areas.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) recording of a temporal lobe seizure. The ictal EEG pattern is shown in the rectangular areas.

This article focuses on 2 related questions, as follows:

-

Is the spell an epileptic seizure?

-

If the event is epileptic, is it likely to recur?

Thus, the stepwise approach should be the following:

-

Is it a seizure?

-

Is it epilepsy?

-

What kind of epilepsy?

-

What is the cause?

This article describes the common clinical features of patients with a first seizure, risk factors for seizure recurrence, and a general approach to management.

Definitions

The definitions of the following terms come from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Guidelines. [3, 4, 5] In 2017, the ILAE proposed revisions to the terminology, classification, and concepts for seizures and epilepsies, but the ILAE indicates these are guiding principles rather than a presentation of new classification per se. [6, 7]

An epileptic seizure is a clinical event presumed to result from an abnormal and excessive neuronal discharge. The clinical symptoms are paroxysmal and may include impaired consciousness and motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic events perceived by the subject or an observer.

Epilepsy occurs when 2 or more epileptic seizures occur unprovoked by any immediately identifiable cause. The seizures must occur more than 24 hours apart. In epidemiologic studies, an episode of status epilepticus is considered a single seizure. Febrile seizures and neonatal seizures are excluded from this category.

Idiopathic epilepsy describes epilepsy syndromes with specific age-related onset, specific clinical and electrographic characteristics, and a presumed genetic mechanism.

Epileptic seizures are classified as cryptogenic or symptomatic. A cryptogenic seizure is a seizure of unknown etiology, and it is not associated with a previous central nervous system (CNS) insult known to increase the risk of developing epilepsy. A cryptogenic seizure does not conform to the criteria for the idiopathic or symptomatic categories. Previous studies use the term idiopathic to describe a seizure of unknown etiology. However, the ILAE guidelines discourage use of the term idiopathic to describe a seizure of unknown etiology.

Symptomatic seizure is a seizure caused by a previously known or suspected disorder of the CNS. This type of seizure is associated with a previous CNS insult known to increase the risk of developing epilepsy.

An acute symptomatic seizure is one that occurs following a recent acute disorder such as a metabolic insult, toxic insult, CNS infection, stroke, brain trauma, cerebral hemorrhage, medication toxicity, alcohol withdrawal, or drug withdrawal. An example of an acute symptomatic seizure is a seizure that occurs within 1 week of a stroke or head injury. Studies have reported that 25-30% of first seizures are acute symptomatic seizures. [8]

A remote symptomatic seizure is a seizure that occurs longer than 1 week following a disorder that is known to increase the risk of developing epilepsy. The seizure may occur a long time after the disorder. These disorders may produce static or progressive brain lesions. An example of a remote symptomatic seizure is a seizure that first occurs 6 months following a traumatic brain injury or stroke.

Seizures are also classified as provoked or unprovoked. A provoked seizure is an acute symptomatic seizure. An unprovoked seizure is a cryptogenic or a remote symptomatic seizure.

Compared with an epileptic seizure, a nonepileptic event is a clinical event that can mimic, and be mistaken for, an epileptic seizure. Examples of nonepileptic events that mimic seizures include syncope and psychogenic nonepileptic attacks (PNEAs). Syncope is caused by decreased cerebral perfusion that results mostly from a decrease in the cardiac output, which results in loss of consciousness.

For more information on some of the topics discussed here, see the following:

Etiology

Causes of epilepsy include the following:

-

Prenatal, perinatal, or postnatal complications of pregnancy and delivery

-

Febrile seizure, which must be differentiated between a complex febrile seizure and a simple febrile seizure

-

Cerebrovascular disease, such as cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and venous thrombosis

-

Head trauma, which is more significant when it occurs with loss of consciousness lasting longer than 30 minutes, posttraumatic amnesia lasting longer than 30 minutes, focal neurologic findings, or neuroimaging findings suggesting a structural brain injury

-

Central nervous system (CNS) infections, such as meningitis or encephalitis

-

Neurodegenerative diseases

-

Autoimmune disease

-

Brain neoplasm

-

Genetic diseases

-

Drug intoxication, drug withdrawal, or alcohol withdrawal

-

Metabolic medical disorders, such as uremia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia

Risk factors for recurrent seizures include the following:

-

Age younger than 16 years [9] : The risk in this age group is almost double the risk of recurrent seizures in adolescents and adults aged 16-60 years.

-

Previous provoked seizures [11]

-

Previous febrile seizure [8]

-

Family history of epilepsy [8] : Remote symptomatic seizure may occur in a patient whose sibling is affected with epilepsy.

-

Status epilepticus or multiple seizures within 24 hours as the initial remote symptomatic seizure [11]

-

Todd paralysis in patients with a remote symptomatic seizure [11]

-

History of neurologic deficit from birth, such as cerebral palsy or intellectual disability [10]

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan that shows a brain tumor [14]

-

Electroencephalogram (EEG) that shows epileptiform discharges (see below)

Risk of seizure recurrence in patients whose EEG shows epileptiform discharges

In patients with a first seizure and no known etiology, van Donselaar et al’s pooled analyses showed the following 2-year cumulative risks of seizure recurrence [18] : in patients with epileptiform discharges, 83%; in patients with nonepileptiform abnormalities, 41%; and in patients with normal electroencephalogram (EEG), 12%. The investigators obtained a routine EEG in all cases and a second sleep-deprived EEG if the first EEG did not show epileptiform discharges.

Studies in the 1990s also reported the following risks for seizure recurrence:

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 1 in 26 people will develop epilepsy during his or her lifetime. [20]

The incidence of single unprovoked seizures is 23-61 cases per 100,000 persons-years, while the incidence of acute symptomatic seizures is 29-39 cases per 100,000 population per year. [21, 22, 23]

Beghi et al attributed the variability to differences in methodology and definitions. [19] The rates were similar in different geographic areas despite technical differences in the studies.

Racial differences have not been studied, but there appears to be a small to moderate male preponderance of men studies of first adult seizures in most reports. [14, 18, 24, 25] However, in an early study, Annegers et al found a slight overall preponderance of women. [10] Their etiologic categories were neurologic deficit from birth, remote symptomatic, and no known previous etiology. The investigators identified a preponderance of men in the group with neurologic deficit from birth, no sex preponderance in the group with remote symptomatic seizures, and a slight preponderance of women in the group with no known previous etiology. [10] These authors did not determine if these sexual differences were statistically significant.

Among patients who had an initial generalized tonic-clonic seizure, Bora et al found that only 45.5% were men. [15] Patients with partial seizures and structural lesions proven on computed tomography (CT) scan were excluded from this study.

Age does affect the incidence rate of epilepsy, with the highest incidence in the very young and very old groups. The incidence rate in children younger than 1 year is 100-233 per 100,000. [26] The rate decreases in patients aged 20-60 years to 30-40 cases per 100,000, but the rate increases to 100-170 cases per 100,000 in patients older than 65 years. [26]

Prognosis

A first seizure provoked by an acute brain insult is unlikely to recur (3-10%), whereas a first unprovoked seizure has a recurrence risk of 30-50% over the next 2 years. Even among symptomatic seizures, the recurrence rate differs according to the underlying cause. Seizures associated with reversible metabolic or toxic disturbances are associated with a minor risk of subsequent epilepsy (3% or less based on large case series). Seizures provoked by disorders that cause permanent damage to the brain, such as brain abscess, have a higher risk of recurrence (10% or more). [8]

In a 2009 study, individuals with a first acute symptomatic seizure were found to be significantly more likely to die in the first 30 days after the seizure compared with those with a first unprovoked seizure [27] ; however, the risk of 10-year mortality did not differ. In addition, the risk for subsequent unprovoked seizure was 80% lower in the group with first acute symptomatic seizure compared with those with first unprovoked seizure. [27]

Among medically untreated patients in one study, the cumulative 2-year risk of seizure recurrence was 51%. [9] Hauser et al found that variability in the reported risks of seizure recurrence may have been due to the following [11] :

-

Variations in patient populations: Some studies reflect the risk in referral populations; other studies reflect the risk in a more general patient population.

-

Variations in the specificity and sensitivity of case definitions

-

Misclassification of cases: Hauser et al found that 74% of their patient cohort required exclusion because of a previous unprovoked seizure. [26]

-

Variations in time of ascertainment

-

Biases from retrospective study design

-

Confounding effect of anticonvulsant treatment: Many of the previous studies included patients who received anticonvulsant therapy after their first seizure.

See Etiology for risks factors associated with seizure recurrence.

Patient Education

Counseling patients about driving after a first seizure revolves around 2 issues: the diagnosis and the chance of recurrence.

Patients who have had a single epileptic seizure are at increased risk of having a second seizure. Therefore, these individuals should be informed that they are at increased risk of injury to themselves or others if another seizure occurs. Risk of injury is especially important if patients are driving, operating dangerous machinery, or performing other activities that could put themselves or others at risk. These same concerns also apply to nonepileptic conditions such as syncope that might recur and put the patient or others at risk of injury. Document this discussion in the patient’s medical record.

The patient should be advised to contact the state agency that regulates driving privileges, as driving regulations vary from state to state. The restrictions sometimes apply to any alteration or loss of consciousness from any etiology. This discussion with the patient should also be documented in the medical record.

Patients with a first epileptic seizure and with risk factors such as remote symptomatic etiology or an electroencephalogram (EEG) with epileptiform discharges are at higher risk for a second seizure. Restrictions of hazardous activity should be more emphatic for these patients.

For patient education information, see the Brain and Nervous System Center, as well as Epilepsy.

-

An electroencephalogram (EEG) recording of a temporal lobe seizure. The ictal EEG pattern is shown in the rectangular areas.

-

An electroencephalogram (EEG) recording from a patient with primary generalized epilepsy. A burst of bilateral spike and wave discharge is shown in the rectangular area.

-

An electroencephalogram (EEG) recording of a seizure from a subdural array in a patient evaluated for epilepsy surgery. The subdural electrodes record from the left anterior temporal (LAT), left middle temporal (LMT), and left posterior temporal (LPT) regions. The EEG seizure pattern is seen best in bipolar EEG channels LAT 3-4 and LMT 3-4 (rectangular areas).