Background

The radial nerve is a peripheral nerve originating from the ventral roots of the spinal nerves C5-T1. An extension of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, it supplies both sensory and motor function to the upper extremity. Motor functions include innervation to the triceps brachii, posterior forearm compartment, and the extrinsic extensor muscles of the wrist and fingers. Sensory function includes cutaneous innervation of segments of the anterolateral arm, distal posterior arm, posterior forearm, and dorsal surface of the first three digits of the hand and the lateral half of the ring finger. [1, 2]

Due to the close proximity of the radial nerve to the humerus shaft, radial neuropathies most commonly result from fractures of the arm; other causes include penetrating wounds, compression, and ischemia. [3] Radial neuropathies can occur from surgical procedures such as humeral nailing performed to stabilize an acute humeral fracture. [4] Saturday night palsy, a radial nerve compression injury, commonly results from placing one’s arm over the backrest of a chair.

The pattern of clinical involvement is dependent on the mechanism, severity, and the level of injury. The most commonly reported symptom is loss of wrist extension (“wrist drop”). [5] However, affected patients can also present with sensory symptoms including pain, paresthesia, and numbness as well as motor symptoms of weakness involving extension of the elbow and fingers.

Management depends on the severity and mechanism of injury. Closed humerus fractures are often managed with conservative nonsurgical treatment, with failure of spontaneous recovery warranting surgical exploration. However, the appropriate timing of surgical exploration for radial nerve injuries remains controversial. Radial nerve injuries resulting from open humerus fractures are managed with surgical exploration and, if necessary, repair including primary neurorrhaphy and neural grafting. [6]

Pathophysiology

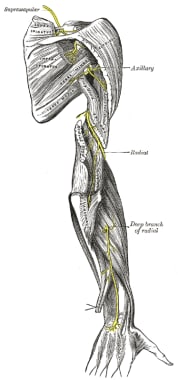

An introduction to radial nerve anatomy is essential for understanding the common mechanisms and locations of its injury. The radial nerve receives root innervation from C5-T1 spinal roots. It branches from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, exiting the axilla posterior to the brachial axilla . In the upper arm, the radial nerve gives off motor branches to the triceps and anconeus muscles before it wraps around the humerus at the spiral groove (also known as the radial groove). Three sensory branches, which supply the skin over the triceps and posterior forearm, also are given off at this level. Here, its proximity to the humerus makes it susceptible to compression and/or trauma.

After exiting the spiral groove, the radial nerve supplies the brachioradialis muscle before passing over the lateral epicondyle and into the cubital fossa and forearm. Here, the radial nerve divides into the deep posterior interosseous branch and a sensory branch. The posterior interosseous branch is a pure motor nerve that supplies the supinator and then dives into the supinator through the fascia to supply the muscles of the wrist and finger extension. Known as the radial tunnel, this fascia is another common site for nerve damage to occur. The sensory branch arises near the elbow and travels down the forearm with the radial artery, inferiorly to the anterolateral portion of the radius deep to the brachioradialis. It becomes superficial at the wrist as it courses over the distal radius and over the anatomical snuffbox before it supplies the lateral aspect of the dorsum of the hand and the lateral three and a half digits (thumb, index finger, middle finger, and lateral half of the ring finger). [2] See the image below.

Mechanisms of radial mononeuropathies

Crutch palsy

A compressive neuropathy that results from prolonged, direct pressure on the axilla, such as from a crutch. Patients often present with triceps weakness along with wrist and finger extensor weakness and paresthesia in the posterior forearm, posterior hand, and posterolateral portion of the last three and a half digits. Management is conservative with wrist splinting and the removal of external compression, including discontinuation of axillary crutches.

Saturday night palsy

A compressive neuropathy resulting from prolonged direct pressure against a firm object on the upper medial arm or axilla such as draping one’s arm over furniture. This injury often occurs in the setting of alcohol intoxication and deep sleep on the affected arm. Patients may present with motor symptoms including wrist drop and weakness in arm extension and sensory symptoms including numbness, tingling, and pain in the radial nerve distribution. Treatment is supportive with NSAIDs, steroids, and rest along with wrist splinting.

Honeymooner’s palsy

Another compressive neuropathy involving an individual falling asleep on the arm of another and resulting in compression of the person’s radial nerve. Similar to the presentation of Saturday night palsy, symptoms include wrist drop and sensory deficits affecting portions of the posterior forearm, hand, and fingers. Treatment involves supportive therapy with removal of external compression.

Humeral shaft fractures

Humeral shaft fractures account for 1–3% of all fractures. [7] Given the proximity of the radial nerve to the humerus bone, humeral shaft fractures are the most common cause of radial nerve mononeuropathy, with a metanalysis of 25 studies showing an overall prevalence of 11.8%. Transverse spiral fractures between the middle and distal parts of the humerus are more likely to be associated with radial nerve injury. [3] Clinical presentations vary depending on the location of the fracture and nerve injury. Patients with spiral groove fractures typically present with loss of wrist and finger extension but spare the triceps and arm extension. Patients also present with sensory deficits including loss of sensation to portions of the posterior forearm and dorsum of the hand. [8] Treatment of radial mononeuropathies related to open fractures involves early surgical exploration, while those injuries due to closed fractures are initially managed with conservative therapy followed by surgical exploration if spontaneous recovery does not occur.

Supinator syndrome (posterior interosseous nerve syndrome)

Supinator syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy at the level of the supinator muscle in the arcade of Frohse (proximal border of the supinator muscle) caused by compression of the deep branch of the radial nerve passes between the heads of the supinator muscle before it becomes the posterior interosseous nerve. Supinator syndrome results from excessive supinator or pronation and commonly occurs in tennis players. Patients can present with elbow and lateral upper forearm pain and weakness in finger extension. Sensory function is preserved, as the superficial radial nerve branches off above the arcade of Frohse. Treatment involves non-surgical management with splinting, NSAIDs, and activity modification. Surgical decompression may be indicated if conservative management fails.

Radial tunnel syndrome

This is a compressive neuropathy of the posterior interosseous nerve in the proximal forearm that presents with pain over the radial tunnel, which is located along the lateral aspect of the forearm. Although similar to supinator syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome lacks motor weakness. Treatment is similar to supinator syndrome.

Cheiralgia paresthetica (superficial radial neuropathy)

This is a compression or entrapment neuropathy of the superficial radial nerve over the lateral wrist characterized by sensory disturbances including pain, numbness, and/or tingling in the dorsal and radial aspect of the wrist and hand. Also known as handcuff neuropathy, the superficial radial neuropathy can result from tightened handcuffs or watchbands. Treatment is mainly conservative along with removal of sources of external compression.

Epidemiology

Frequency

The exact prevalence of radial mononeuropathy is unknown, as there are currently no recent epidemiologic studies in the literature. Their reporting in the scientific literature consists mainly of case reports.

Despite the lack of recent studies, one study using a closed claims database in the 1990s investigated nerve injury associated with anesthesia in the United States and found 15 cases of radial nerve injury out of 670 (2%) nerve injury claims as opposed to 190 ulnar nerve injuries (28%). [9]

Demographics

No racial preponderance is known. No gender predilection has been observed. Radial neuropahty is reported in all age groups.

However, mononeuropathies are rare among children and account for less than 10% of pediatric referrals for electromyographic testing [10] with ulnar mononeuropathy being the more frequently seen pediatric mononeuropathy. [11, 12]

In adults, radial mononeuropathy most commonly occurs at the spiral groove of the humerus. In contrast, a retrospective analysis of 19 children and adolescents ages one month to 19 years showed predominant localization to the posterior interosseous nerve or at the distal main radial trunk. [13]

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on the degree and type of radial nerve injury.

-

In most cases, in which the cause is successfully treated, patients will fully recover. However, in some cases, there may be residual partial or complete loss of movement or sensation

-

Most neuropathies usually representing neurapraxia and axonotmesis and caused by external compression will recover spontaneously or with conservative therapy within 2–4 months.

-

There is debate in the literature on the appropriate timing of surgical exploration of radial nerve injuries associated with closed humerus fractures. Most clinicians recommend surgical exploration if there is no recovery within 8–10 weeks. However, the opposing view advocates for early operative exploration, citing that nerve lacerations in up to 20% to 42% of cases associated with closed humeral shaft injuries show improved outcomes over delayed nerve repair. [6]

-

In a metanalysis of 23 articles looking at radial nerve palsies associated with humeral shaft fractures, spontaneous radial nerve recovery occurred in 77.2% of patients. Patients who failed conservative nonsurgical management and subsequently underwent nerve exploration more than 8 weeks after their injury had a 68.1% recovery rate compared to 89.8% of patients who underwent surgical exploration within 3 weeks of injury. [14]

-

In cases where recovery fails, tendon transfer surgery may provide adequate hand function.

-

Electromyographic testing may help not only to localize the lesion but also to provide prognostic information.

Patient Education

Discussing prognosis and possible complications in order to manage patient expectations and satisfaction is important. Patients should be educated on strategies and lifestyle modifications to prevent recurrence or worsening of injury. For example, in patients with posterior interosseous lesions, discuss the avoidance of activities involving repetitive pronation/supination of the forearm.

-

The Radial Nerve from Gray's Anatomy (published 1918, public domain, copyright expired).