Practice Essentials

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), or childhood epileptic encephalopathy, is a pediatric epilepsy syndrome characterized by multiple seizure types; intellectual disability or regression; and abnormal findings on electroencephalography (EEG). See the image below.

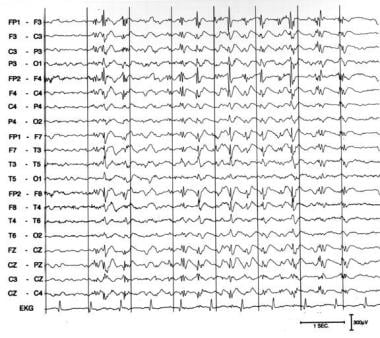

Slow spike wave pattern in a 24-year-old awake male with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. The slow posterior background rhythm has frequent periods of 2- to 2.5-Hz discharges, maximal in the bifrontocentral areas, occurring in trains as long as 8 seconds without any clinical accompaniment.

Slow spike wave pattern in a 24-year-old awake male with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. The slow posterior background rhythm has frequent periods of 2- to 2.5-Hz discharges, maximal in the bifrontocentral areas, occurring in trains as long as 8 seconds without any clinical accompaniment.

Signs and symptoms

If not present before symptom onset, neurologic and neuropsychologic deficits inevitably appear during the evolution of LGS. Factors associated with more common or more severe intellectual disability include the following:

-

An identifiable etiology (ie, symptomatic as opposed to cryptogenic LGS)

-

A history of West syndrome (infantile spasm)

-

Onset of symptoms before age 12-24 months

-

More frequent seizures

Average intelligence quotient (IQ) score is significantly lower in patients with symptomatic LGS than in those with cryptogenic LGS. Earlier age of seizure onset is correlated with higher risk of cognitive impairment.

Ictal clinical manifestations include the following:

-

Tonic seizures (frequency, 17-95%) - Can occur during wakefulness or sleep but are more frequent during non–rapid eye movement (REM) sleep; may be axial, axiorhizomelic, or global; may be asymmetric

-

Atypical absence seizures (frequency, 17-100%) – Can have gradual onset, with incomplete loss of consciousness; associated eyelid myoclonias may be noted

-

Atonic, massive myoclonic, and myoclonic-atonic seizures (frequency, 10-56%) – Can all cause a sudden fall, producing injuries, or may be limited to the head falling on the chest; pure atonic seizures are exceptional

-

Other types of seizures (generalized tonic-clonic [15%], complex partial [5%], absence status epilepticus, tonic status epilepticus, nonconvulsive status epilepticus)

Findings on general physical examination are normal in many cases. No physical findings are pathognomonic for LGS. Nevertheless, the general physical examination can help identify specific etiologies that have both systemic and neurologic manifestations.

No neurologic examination findings are pathognomonic for LGS. However, neurologic examination of an LGS patient may demonstrate the following:

-

Abnormalities in mental status function (specifically, deficits in higher cognitive function consistent with intellectual disability)

-

Abnormalities in level of consciousness, cranial nerve function, motor/sensory/reflex examination, cerebellar testing, or gait (nonspecific findings that are more a reflection of the underlying brain injury/abnormality or the effect of anticonvulsant medications)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

No laboratory investigations are known to aid in the diagnosis of LGS.

EEG (waking and sleep) is an essential part of the workup. Interictal EEG may demonstrate the following characteristics:

-

A slow background that can be constant or transient

-

Awake – Diffuse slow spike wave

-

Non-REM sleep – Discharges that are more generalized and more frequent, consisting of polyspikes and slow waves

-

REM sleep – Decreased spike waves

Ictal EEG may demonstrate the following characteristics:

-

Tonic seizure – Diffuse, rapid, low-amplitude activity pattern that progressively decreases in frequency and increases in amplitude; may be preceded by a brief generalized discharge of slow spike waves or flattening of the recording or followed by diffuse slow waves and slow spike waves; no postictal flattening

-

Atypical absence seizure – Diffuse, slow, and irregular spike waves; occasionally, discharges of rapid rhythms preceded by flattening of the record for 1-2 seconds, followed by progressive development of irregular fast rhythm in anterior and central regions and ending with brief spike waves

-

Atonic, massive myoclonic, or myoclonic-atonic seizure – Slow spike waves, polyspike waves, or rapid diffuse rhythms

-

Absence status epilepticus – Continuous spike wave discharges, usually at a lower frequency than at baseline, and rapid rhythms during tonic status epilepticus

Neuroimaging is an important part of the search for an underlying etiology. Modalities include the following:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – Generally preferred, may require sedation

-

Computed tomography (CT) – Preferred in selected situations, e.g., to assess for acute processes such as hemorrhage or if timely MRI is not available

-

Routine positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission CT (SPECT) – Lacking current indications for LGS but may be useful in potential candidates for epilepsy surgery

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical treatment options may be divided into the following 3 major groups:

-

First-line treatments based on clinical experience or conventional wisdom – valproic acid, benzodiazepines (specifically, clonazepam, nitrazepam, and clobazam; there have been occasional reports of worsening of tonic seizures by benzodiazepines)

-

Treatments suspected to be effective on the basis of open-label uncontrolled studies – vigabatrin, zonisamide

-

Treatments proven effective by double-blind placebo-controlled studies – lamotrigine, topiramate, felbamate, rufinamide, clobazam, cannabidiol

Surgical options include the following:

-

Corpus callosotomy – Effective in reducing drop attacks but not typically helpful for other seizure types; considered palliative rather than curative

-

Vagus nerve stimulation – FDA-approved as adjunctive treatment for refractory partial-onset seizures in adults and adolescents older than 12 years

-

Focal cortical resection – May improve seizure control in rare cases

Dietary therapies, including the ketogenic diet and modified Atkins diet—involving a high ratio of fats (ketogenic foods) to proteins and carbohydrates (antiketogenic foods)—may be useful in patients with LGS refractory to medical treatment.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Childhood epileptic encephalopathy, or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), is a devastating pediatric epilepsy syndrome constituting 1-4% of childhood epilepsies. [1] The syndrome is characterized by multiple seizure types; intellectual disability or regression; and abnormal findings on electroencephalogram (EEG), with paroxysms of fast activity and generalized slow spike-and-wave discharges (1.5-2 Hz).

The most common seizure types are tonic-axial, atonic, and absence seizures, but myoclonic, generalized tonic-clonic, and partial seizures can be observed (see Clinical Presentation). An EEG is an essential part of the workup for LGS. Neuroimaging is an important part of the search for an underlying etiology (see Workup).

A variety of therapeutic approaches are used in LGS, ranging from conventional antiepileptic agents to diet and surgery (see Treatment and Management). Unfortunately, much of the evidence supporting these approaches is not robust, and treatment is often ineffective.

See the following articles for more information:

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of LGS is not known. No animal models exist.

A variety of possible pathophysiologies have been proposed. One hypothesis states that excessive permeability in the excitatory interhemispheric pathways in the frontal areas is present when the anterior parts of the brain mature.

Involvement of immunogenetic mechanisms in triggering or maintaining some cases of LGS is hypothesized. Although one study found a strong association between LGS and the human lymphocyte antigen class I antigen B7, a second study did not. No clear-cut or homogeneous metabolic pattern was noted in 2 separate reports of positron emission tomography (PET) studies in children with LGS.

Etiology

LGS can be classified according to its suspected etiology as either idiopathic or symptomatic. Patients may be considered to have idiopathic LGS if normal psychomotor development occurred prior to the onset of symptoms, no underlying disorders or definite presumptive causes are present, and no neurologic or neuroradiologic abnormalities are found. In contrast, symptomatic LGS is diagnosed if a likely cause can be identified as being responsible for the syndrome.

Population-based studies have found that 70-78% of patients with LGS have symptomatic LGS. Underlying pathologies in these cases may include the following:

-

Encephalitis and/or meningitis

-

Tuberous sclerosis

-

Brain malformations (eg, cortical dysplasias)

-

Hypoxia-ischemia injury

-

Frontal lobe lesions

-

Traumatic brain injury

There is a history of infantile spasms in 9-39% of LGS patients.

In addition to idiopathic and symptomatic LGS, some investigators add “cryptogenic” as a third etiologic category. [2] This category encompasses cases in which the epilepsy appears to be symptomatic but a cause cannot be identified. In an epidemiologic study in Atlanta, Georgia, 44% of patients with LGS were in the cryptogenic group. In a series of 23 patients with cryptogenic LGS, 2.5-47.8% had a family history of epilepsy and febrile seizures.

In 2001, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Task Force on Classification and Terminology proposed to include LGS among the epileptic encephalopathies. These are conditions in which not only the epileptic activity but also the epileptiform EEG abnormalities themselves are believed to contribute to the progressive disturbance in cerebral function. [3]

In the revision of the classification of seizures and epilepsy published in 2010, the terms "idiopathic," "symptomatic," and "cryptogenic" were eliminated and replaced by "genetic," "structural/metabolic," and "unknown" to encourage focus on specific underlying mechanisms. [4] However, many neurologists continue to use those terms as described above.

Epidemiology

Overall, LGS accounts for 1-4% of patients with childhood epilepsy but 10% of patients with onset of epilepsy when younger than 5 years. The prevalence of LGS in Atlanta, Georgia, was reported as 0.26 per 1000 live births.

LGS is more common in boys than in girls. The prevalence is 0.1 per 1000 population for boys, versus 0.02 per 1000 population for girls (relative risk, 5.31).

The mean age at epilepsy onset is 26-28 months (range, 1 d to 14 y). The peak age at epilepsy onset is older in patients with LGS of an identifiable etiology than in those whose LGS has no identifiable etiology. The difference in age of onset between the group of patients with LGS and a history of West syndrome (infantile spasm) and those with LGS without West syndrome is not significant. The average age at diagnosis of LGS in Japan was 6 years (range, 2-15 y).

Epidemiologic studies in industrialized countries (eg, Israel, Spain, Estonia, Italy, Finland) have demonstrated that the proportion of epileptic patients with LGS seems relatively consistent across the populations studied and similar to that in the United States. The prevalence of LGS is 0.1-0.28 per 1000 population in Europe. The annual incidence of LGS in childhood is approximately 2 per 100,000 children. [5]

Among children with intellectual disability, 7% have LGS, while 16.3% of institutionalized patients with intellectual disability have LGS.

Prognosis

Long-term prognosis overall is unfavorable but variable in LGS. [6] Longitudinal studies have found that a minority of patients with LGS eventually could work normally, but 47-76% still had typical characteristics (intellectual disability, treatment-resistant seizures) many years after onset and required significant help (eg, home care, institutionalization). [7]

Patients with symptomatic LGS, particularly those with an early onset of seizures, prior history of West syndrome, higher frequency of seizures, or constant slow EEG background activity, have a worse prognosis than those with idiopathic seizures.

Tonic seizures may persist and be more difficult to control over time, while myoclonic and atypical absences appear easier to control.

The characteristic diffuse slow spike wave pattern of LGS gradually disappears with age and is replaced by focal epileptic discharges, especially multiple independent spikes.

Mortality rate is reported at 3% (mean follow-up period of 8.5 y) to 7% (mean follow-up period of 9.7 y). Death often is related to accidents. A high rate of injuries is associated with atonic and/or tonic seizures.

The severity of the seizures, frequent injuries, developmental delays, and behavior problems take a large toll on even the strongest parents and family structures. Pay attention to the psychosocial needs of the family (especially siblings). The proper educational setting also is important to help the patient with LGS reach his or her maximal potential.

Patient Education

Patients and their families need to be informed of the risk for the following severe idiosyncratic reactions from 3 commonly used antiepileptic medications for LGS:

-

Valproate - Hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis

-

Lamotrigine -Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis

-

Felbamate - Aplastic anemia, hepatotoxicity

For patient education information, see the Brain and Nervous System Center, as well as Epilepsy.

-

Patient with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome wearing a helmet with face guard to protect against facial injury from atonic seizures

-

Slow spike wave pattern in a 24-year-old awake male with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. The slow posterior background rhythm has frequent periods of 2- to 2.5-Hz discharges, maximal in the bifrontocentral areas, occurring in trains as long as 8 seconds without any clinical accompaniment.