Practice Essentials

Background

Intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) was first described in 1760 by Sir Percival Pott, who also documented the associated scalp swelling, known as Pott puffy tumor. IEAs are less common than intraparenchymal brain abscesses and subdural empyemas.

Pathophysiology

An intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) is a suppurative infection of the epidural space, which refers to the space between the dura mater and the inner table of the skull (see the image below). As the dura adheres tightly to the skull and provides a barrier to the spread of the infection, IEAs tend to appear well-circumscribed radiologically, and may progress subacutely. There is often associated osteomyelitis of the overlying bone. [1, 2] IEAs most commonly are associated with sinusitis and otologic infections, although with modern antibiotic treatment, the incidence has declined. IEAs may also occur as a complication of neurosurgical procedures (ie,. iatrogenic IEAs) or as a sequale of head trauma. [3] As many as 1%–3% of craniotomies result in an IEA, in particular those with frontal sinus breaches. [4, 5] In approximately 10% of cases, an IEA is associated with a subdural empyema, a pyogenic infection between the dura and arachnoid mater, which is more rapidly progressive and carries a poorer prognosis. At autopsy, however, 81% of patients with IEAs have been found to have evidence of subdural extension of the infection, 35% of patients with meningitis, and 17% with intraparenchymal abscess.

IEAs most commonly result from direct, contiguous spread of an infection from the paranasal sinuses (eg, frontal sinus), middle ear (eg, from otitis media), orbit, or mastoids (eg, from mastoiditis). Direct contamination may result from penetrating trauma, contamination of the wound perioperatively, or direct spread from associated osteomyelitis. Less commonly, IEAs result from septic emboli entering via emissary veins, or via hematogenous spread. [6]

The most common causative organisms among non-neurosurgical IEAs are streptococci and anaerobes, particularly when associated with sinusitis. Among traumatic and neurosurgical-associated IEAs, staphylococci (in particular S. aureus) are the most common pathogens, and less commonly gram-negative bacteria.

Once the organism enters the epidural space, hyperemia and fibrin deposition occurs, followed by collection of purulent material and development of chronic granulation and fibrous tissue. Dural attachments, especially at sutures, help to contain the infection. However, when this barrier is compromised because of trauma or surgery, further spread of the infection may ensue, resulting in complications such as osteomyelitis of the bone flap, subdural empyema, dural sinus or coritcal vein thrombosis, purulent leptomeningitis, and intraparenchmyal brain abscess. Virulence of the organism, immune resistance of the host (eg, in immunocompromised patients), and prompt treatment influence the outcome of this condition significantly.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) is an uncommon cause of focal intracranial infections; in fact, 90% of epidural abscesses occur in the spine. Because of early and adequate treatment of bacterial middle ear and sinus infections, particularly in children, [7] IEAs have become less common. Most iatrogenic IEAs after neurosurgical procedures are associated with a superficial surgical site infection (SSIs). Although the incidence of SSIs has been on the decline with more standardized use of perioperative antibiotics and sterile operating room procedures, SSIs still occur in 1%–6% of cases. [8] IEAs complicate 1%–3% of craniotomies overall, although at a significantly higher rate in cases of frontal sinus breaches and reoperations. [9, 10, 4, 5]

Mortality/Morbidity

Mortality from IEAs was 100% in the pre-antibiotic era. With advanced imaging techniques, more effective antibiotics, and prompt surgical treatment, the mortality rate has declined to 6%–20%.

The outcome of patients with IEAS is influenced by neurological status on presentation (eg, presence of altered mental status), whether neurological deterioration occurs, age, comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes, immunocompromised states), virulence of the organism, and delays in beginning appropriate treatment. The primary causes of poor outcome among patients with IEAs are mass effect of the lesion resulting in brain herniation, and extension of the infection into the venous system, which may lead to venous thrombosis and fulminant cerebral edema and leptomeningitis. In an older study, Harris et al. reported 31 cases of localized central nervous system infection over a 7-year period in their community hospital. [11] The authors found subdural empyemas in 6 cases (20%) and IEAs in 2 cases (6%). Although all patients with cranial subdural empyema and cranial epidural abscess survived, half had severe residual neurologic deficits. With the advent of new antibiotics, improved surgical techniques, and aggressive surgical approach, prognosis has significantly improved.

Germiller et al. report a consecutive sample of 25 children and adolescents treated for 35 intracranial complications associated with intracranial complications of sinusitis. [12] Epidural abscess was most common (13 complications) followed by subdural empyema (n = 9), meningitis (n = 6), encephalitis (n = 2), intracerebral abscess (n = 2), and dural sinus thrombophlebitis (n = 2). Only 1 death occurred from sepsis secondary to meningitis (mortality 4%) and only 2 patients had permanent neurologic sequelae. In another study of the pediatric population by Lundy et al., the authors identified 16 children, 14 of whom had subdural empyemas and 2 who had IEAs only. Although all children with subdural empyemas had neurological manifestions of the disease, those with only IEA did not. One child in the series died. The authors noted that delays in treatment were in part due to delays in obtaining appropriate imaging. [7]

Sex- and age-related demographics

IEAs occurs with greater frequency in boys and men compared to girls and women (ratio of 1:0.56, respectively). [13]

Non-iatrogenic IEAs are more common in older children, adolescents, and younger adults, primarily due to the higher incidence of otologic infections and sinusitis. Iatrogenic IEAs, however, may occur at any age, in particular among the elderly with comorbidities that may comprise immune response and/or wound healing. [13, 14]

Prognosis

If identified and treated promptly before neurological deterioration occurs, the prognosis for intracranial epidural abscess (IEA) is very good.

Because of the insidious onset of symptoms, neuroimaging by CT scanning and MRI as well as the availability of strong antibiotics have resulted in decreased morbidity and mortality from this condition in recent years.

Signs associated with an excellent prognosis include the following:

-

Young age

-

No altered mental status

-

Absence of severe neurologic deficit on initial presentation

-

Absence of neurologic deterioration during initial management

-

No comorbid factors (eg, immunocompromised)

Poorer prognosis is often associated with the following:

-

Signs of herniation present on initial presentation, when the mortality rate exceeds 50%

-

Failure to obtain a brain CT scan in patients with altered mental status, headache, or new neurologic deficit

-

Failure to address family concerns about unusual patient behavior, especially when other symptoms indicative of intracranial epidural abscess are present

Early and accurate diagnosis of this potentially deadly but treatable disease is of paramount importance.

Pradilla et al. report that prognosis for both spinal epidural abscesses and intracranial epidural abscesses worsens if there is delayed diagnosis and intervention, and that prognosis largely depends on the neurologic status at the time of diagnosis. Increased clinical awareness can help achieve an earlier diagnosis, and hopefully improve outcomes. [13]

-

CT scan showing lenticular-shaped intracranial epidural abscess.

-

Intracranial epidural abscess. Enhanced MRI of the brain, axial section, revealing a left temporal epidural abscess with an abscess cavity and a thickened enhancing capsule. Adjacent thickened dura enhances as well. In addition, mass effect is evident.

-

Intracranial epidural abscess. A coronal section of the MRI revealing a left temporal epidural abscess with an abscess cavity and a thickened enhancing capsule. Adjacent thickened dura enhances as well. In addition, mass effect is evident.

-

Intracranial epidural abscess. MRI of the brain, unenhanced. A T1-weighted image (axial view) showing a left temporal epidural abscess with an abscess cavity, surrounding capsule, and the thickened dura underneath. Mass effect is evident.

-

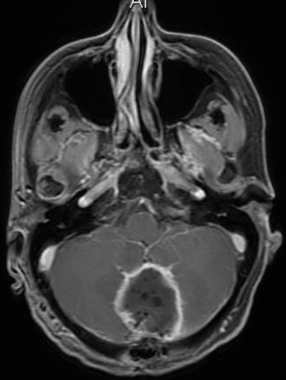

Epidural abscess in the posterior fossa following a suboccipital craniectomy.

-

Epidural abscess photo, taken intraoperatively.