Background

One of the more common causes of acute hepatitis is hepatitis A virus (HAV), which was isolated by Purcell in 1973. Humans appear to be the only reservoir for this virus. Since the application of accurate serologic tests in the 1980s, the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and natural history of hepatitis A have become apparent.

The relative frequency of HAV as a cause of acute hepatitis has declined in Western societies, while in contrast, notification of individual cases has increased, primarily as a result of improved reporting and diagnostic techniques. The nadir of reported cases was in 1987.

Improvements in hygiene, public health policies, and sanitation have had the greatest impact on hepatitis A. Vaccination and passive immunization have also successfully led to some reduction in illness in high-risk groups.

Reduced encounters with HAV at a young age have resulted in both a decline in herd immunity and a change in the epidemiology of the illness, with increases in the mean age of occurrence of illness attributed to acute HAV infection in Western societies. Although this phenomenon may lay a framework for potential epidemics in the future, public health policies and newly implemented immunization practices are likely to reduce this potential.

See the following for more information:

Pathophysiology

HAV is a single-stranded, positive-sense, linear RNA enterovirus of the Picornaviridae family. In humans, viral replication depends on hepatocyte uptake and synthesis, and assembly occurs exclusively in the liver cells. Virus acquisition results almost exclusively from ingestion (eg, fecal-oral transmission), although isolated cases of parenteral transmission have been reported.

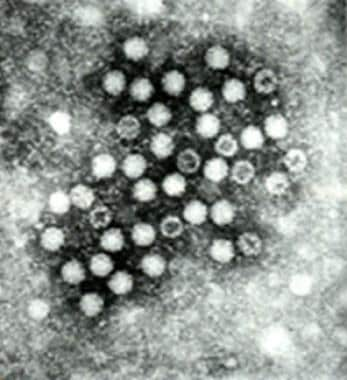

HAV is an icosahedral nonenveloped virus, measuring approximately 28 nm in diameter (see the image below). Its resilience is demonstrated by its resistance to denaturation by ether, acid (pH 3.0), drying, and temperatures as high as 56°C and as low as -20°C. The hepatitis A virus can remain viable for many years. Boiling water is an effective means of destroying it. Chlorine and iodine are similarly effective.

Various genotypes of HAV exist; however, there appears to be only 1 serotype. Virion proteins 1 and 3 are the primary sites of antibody recognition and subsequent neutralization. No antibody cross-reactivity has been identified with other viruses causing acute hepatitis. Evidence in recent years appears to show that the exosomes play a dual role in the transmission of HAV and HCV, allowing these viruses to evade antibody-mediated immune responses but, paradoxically, can also be detected by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) leading to innate immune activation and type I interferon production. [1]

Liu et al performed phylogenetic and recombination analyses on 31 complete HAV genomes from infected humans and simians. They identified 3 intra-genotypic recombination events (I-III), which they believe demonstrate that humans can be co-infected with different HAV subgenotypes. [2]

The first recombination event (I) occurred between the lineage represented by the Japanese isolate AH2 (AB020565, subgenotype IA), and the second event (II) occurred between the lineage represented by the North African isolate MBB (M20273, subgenotype IB). [2] These 2 recombination events resulted in the recombinant Uruguayan isolate HAV5 (EU131373).

The third recombination event (III) occurred between the North African lineage (isolate MBB; M20273, subgenotype IB) and the German lineage (isolate GBM; X75215, subgenotype IA), leading to the Italian isolate FG (X83302). [2]

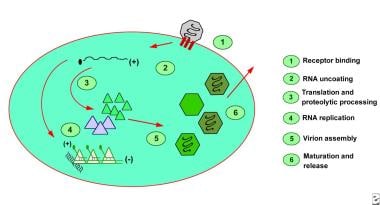

Hepatocyte uptake involves a receptor, identified by Kaplan et al, on the plasma membrane of the cell, and viral replication is believed to occur exclusively in the hepatocytes. [3] The demonstration of HAV in the saliva has raised questions about this exclusivity. After entry into the cell, viral RNA is uncoated, and the host ribosomes bind to form polysomes. Viral proteins are synthesized, and the viral genome is copied by a viral RNA polymerase (see the image below). Assembled virus particles are shed into the biliary tree and excreted in the feces.

Minimal cellular morphologic changes result from hepatocyte infection. The development of an immunologic response to infection is accompanied by a predominantly portal and periportal lymphocytic infiltrate and a varying degree of necrosis.

Many authorities believe that hepatocyte injury is secondary to the host’s immunologic response. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of cytotoxic activity in tissue culture and correlations between immunologic response and the manifestations of hepatocyte injury.

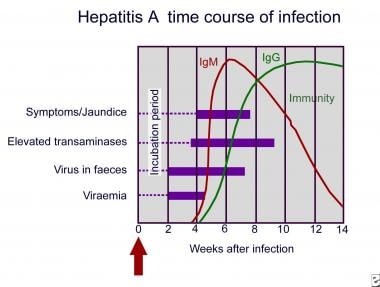

Person-to-person contact is the most common means of transmission and is generally limited to close contacts. Transmission through blood products has been described. The period of greatest shedding of HAV is during the anicteric prodrome (14-21 d) of infection and corresponds to the time when transmission is the highest (see the image below). Recognizing that the active virus is shed after the development of jaundice is important, although the quantity falls rapidly.

Outbreaks of acute hepatitis A have received international attention. The most notable report of transmission appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2005. [4] This report describes a point source epidemic of HAV infection at a Pennsylvania restaurant where the vehicle for transmission was green onions used to make a mild salsa. The contamination of the onions occurred before the vegetable arrived in the United States.

The incubation period usually lasts 2-6 weeks, and the time to the onset of symptoms may be dose related. The presence of disease manifestations and the severity of symptoms after HAV infection directly correlate with the patient's age. In developing nations, the age of acquisition is before age 2 years. In Western societies, acquisition is most frequent in persons aged 5-17 years. Within this age range, the illness is more often mild or subclinical; however, severe disease, including fulminant hepatic failure, does occur.

Etiology

Most patients have no defined risk factors for hepatitis A. Risk factors for the acquisition of hepatitis A include the following:

-

Personal contacts

-

Institutionalization

-

Occupation (eg, daycare)

-

Foreign travel

-

Male homosexuality

-

Illicit parenteral drug use

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Over the last century, improved sanitation and hygiene measures have resulted in a shift in the age group that carries the burden of hepatitis A. This, in turn, may result in more clinically apparent and severe disease.

Until comparatively recently, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data supported cycles of disease occurring every 5-10 years. Some of these outbreaks correlated with the wars of the 20th century, in which people returned from areas of high endemicity. In recent years, this pattern has disappeared and has been associated with a decline in the overall incidence of new infection.

The United States is an area of low endemicity. In contrast, the nearest southern neighbor, Mexico, has a high prevalence of anti-HAV antibody, indicating previous infection. The frequency of acute hepatitis appears to be higher in those US states that are adjacent to Mexico.

In 1988, the number of reported cases of hepatitis A in the United States was 27,000; in 1995, approximately 32,000 infections were reported. The CDC estimated the actual number of infections in 1995 to be approximately 150,000. Subsequent data from the CDC showed that the number of reported acute clinical cases of hepatitis A in 2003 was 7653, with the number of actual clinical cases estimated to be 33,000. The estimated number of new infections in the United States for that same year was 61,000.

Between 1995 and 2006, the reported hepatitis A incidence declined by 90% to the lowest rate ever recorded, 1.2 cases per 100,000 population. [5] (This was paralleled by a similar decline observed in Italy.) The greatest reductions were seen in children and in those states where routine vaccination of children was commenced in 1999. In accordance with these findings, in 2006, the CDC recommended an expansion of routine hepatitis A vaccination to include all children in the United States aged 12-23 months.

Persons aged 5-14 years are most likely to acquire acute HAV infection before the vaccination programs. Over the past 40 years, the average age of infected persons has steadily increased. Evidence of past infection is more prevalent in adults (approximately 40%) than in children (approximately 10%), which supports acquisition during school-aged years.

Individuals in the high-risk populations currently account for many sporadic cases of HAV infection. These groups include contacts of recently infected individuals, foreign travelers (particularly those to developing nations), male homosexuals, childcare workers, institutionalized individuals, and those living in poverty. Health measures implemented for these high-risk groups will likely modify the evolving epidemiology.

US military personnel who served recently in Asia or, more remotely, during World War II often returned with evidence of infection acquired abroad. As many as 200,000 service personnel experienced symptomatic HAV infection in World War II.

Food handlers, at the point of food preparation, are an infrequent source of outbreaks in the United States, although cases have been documented. Virtually any food can be contaminated with HAV.

International statistics

HAV has a worldwide distribution, [6, 7] particularly in resource-poor regions. [8, 9] The highest seropositivity (ie, the highest prevalence of antibody to HAV) is observed in adults in urban Africa, Asia, and South America, where evidence of past infection is nearly universal. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Acquisition in early childhood is the norm in these nations and is usually asymptomatic. Factors predisposing humans to early acquisition include overcrowding, poor sanitation, certain social practices, and lack of a reliable clean water resource. Within the socioeconomic framework (ie, class structure) of some developing nations are differing frequencies of HAV antibody in the older population; accordingly, sporadic cases may be observed in some individuals.

In Shanghai in 1988, a large shellfish-related epidemic occurred. This provided a unique opportunity to study the incubation and natural history of acute HAV infection in a large population. [15]

Immigrants from countries of high endemicity to countries of low endemicity may be responsible for some of the periodicity observed with the outbreaks of infection. In this setting, the affected individuals tend to be infants born since the last outbreak or susceptible adults who moved to the area.

Age-related demographics

With increasing age of acquisition, both symptomatic disease and adverse sequelae increase. In the Shanghai outbreak (see above), most of those admitted to the hospital were aged 20-40 years. Mortality from fulminant hepatic failure increased with increasing age despite the decreasing prevalence of disease as age increased. The lower incidence of infection in the older population was related to a greater likelihood of immunity rather than to a decrease in exposure.

Sex-related demographics

Except for persons in high-risk populations (eg, sewage workers, childcare workers, aid workers, male homosexuals), no sexual predilection is apparent.

Prognosis

In general, the prognosis is excellent. Long-term immunity accompanies HAV infection. Recurrence and chronic hepatitis do not usually occur. Typically, there are no lasting sequelae.

Death is rare, though it is more frequent in elderly patients and in those with underlying liver disease. Annually, an estimated 100 people die in the United States as a result of acute liver failure due to HAV infection. Although the case-fatalities from fulminant HAV infection have been reported in all age groups, where overall the mortality is estimated at approximately 0.3%, the rate is 1.8% among adults older than 50 years and is also higher in persons with chronic liver diseases.

In children, liver transplantation has been performed for fulminant hepatic failure (FHF). In France, 10% of cases of FHF in children are caused by HAV infection. The outcomes from liver transplantation are the same as with others with fulminant disease. Recurrent disease does not occur following liver transplantation despite immunosuppression.

In the United States, most cases are symptomatic, with the frequency of icteric cases approaching 80%. Globally, HAV infection is often asymptomatic and subclinical. Approximately 75% of adults are symptomatic with infection, many with jaundice. In stark contrast, 90% of those infected before age 2 years are asymptomatic.

The single most important determinant of illness severity is age; increasing age is directly correlated with an increasing likelihood of adverse events (ie, morbidity and mortality). Most deaths from acute HAV infection occur in persons older than 50 years, even though such infections are uncommon in this age group. Case fatality rates approach 2%, and the vast majority of persons who acquire infection when older than 50 years exhibit signs and symptoms of the disease.

Other populations with increased likelihood of adverse sequelae caused by acute HAV infection are those with significant comorbidities or concurrent chronic liver disease, as highlighted by the high incidence of hepatitis B surface antigen in persons who died in the Shanghai outbreak, [15] along with case reports of deaths from acute HAV infection in persons with hepatitis C.

Infection in early life occurs commonly in developing countries. Therefore, symptomatic disease is uncommon in natives of these countries and is most often observed in visitors. Seropositivity for anti-HAV protects individuals against reinfection.

Some evidence suggests that reinfection may occur late in life in individuals in whom the levels of detectable antibody have disappeared. Although this phenomenon is reported to occur, reinfection is not associated with clinical disease. A rapid rise in immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody to HAV in the absence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) is the hallmark of this event (anamnestic response).

Complications

Prolonged cholestasis may follow an acute infection. The frequency at which this occurs increases with age. Prolonged cholestasis is characterized by a protracted period of jaundice (>3 mo) and resolves without intervention. Corticosteroids and ursodeoxycholic acid may shorten the period of cholestasis.

The usual features of cholestatic viral hepatitis A are pruritus, fever, diarrhea, and weight loss, with serum bilirubin levels higher than 10 mg/dL. Some investigators believe that the use of corticosteroids may predispose patients to developing relapsing hepatitis A. Good data to support this hypothesis are lacking.

Acute renal failure, interstitial nephritis, pancreatitis, red blood cell aplasia, agranulocytosis, bone marrow aplasia, transient heart block, Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute arthritis, Still disease, lupus-like syndrome, and Sjögren syndrome have been reported in association with HAV. These complications are all rare.

Autoimmune hepatitis after HAV infection has received substantial discussion in the literature. A postulated mechanism involves molecular mimicry and genetic susceptibility. With this condition, as with traditional autoimmune hepatitis, steroid therapy has been associated with good clinical response and improvement in the biochemical and clinical parameters. However, these findings are confined to isolated case reports, and the results of larger clinical trials are not available.

Relapsing HAV infection occurs in 3%-20% of patients with acute HAV infection and uncommonly takes the form of multiple relapses. After a typical acute course of HAV infection, a remission phase occurs, with partial or complete resolution of clinical and biochemical manifestations. The initial flare usually lasts 3-6 weeks; relapse occurs after a short period (usually < 3 wk) and mimics the initial presentation, although it usually is clinically milder.

A tendency to greater cholestasis exists in these patients. Vasculitic skin rashes and nephritis may be additional clinical clues to this syndrome. During relapses, shedding of the virus can be detected. IgM antibody test findings are positive. The clinical course is toward resolution, with lengthening periods between flares. The total duration is 3-9 months.

Liver transplantation has been performed in patients with this condition when signs of significant decompensation have occurred. Corticosteroid treatment has been shown to improve the clinical course, although the course is generally benign without treatment.

Patient Education

Travelers should be educated about good hygiene and clean, safe water supplies. Advice should be provided regarding the benefits of immunization, particularly in high-risk individuals. Travelers should avoid uncontrolled water sources, raw shellfish, and uncooked food. Boiling water or adding iodine inactivates the virus. All fruit should be washed and peeled.

People with HAV infection who are treated at home and those around them should follow strict enteric precautions.

For patient education resources, see the Infections Center, the Digestive Disorders Center, and the Healthy Living Center, as well as Hepatitis A and Foreign Travel.

-

Hepatitis A virus as viewed through electron microscopy.

-

Hepatitis A. Time course of infection.

-

Hepatitis A.