Practice Essentials

Pompe disease (type II glycogen storage disease) is an inherited enzyme defect that usually manifests in childhood. The enzymes affected normally catalyze reactions that ultimately convert glycogen compounds to monosaccharides, of which glucose is the predominant component. This results in glycogen accumulation in tissues, especially muscles, and impairs their ability to function normally.

Signs and symptoms

Most patients experience muscle symptoms, such as weakness and cramps, although certain glycogen storage diseases manifest as specific syndromes, such as hypoglycemic seizures or cardiomegaly.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis depends on muscle biopsy, electromyelography, the ischemic forearm test, creatine kinase levels, patient history, and physical examination findings. Biochemical assay for enzyme activity is the method of definitive diagnosis. [1]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Unfortunately, no cure exists, although diet therapy and enzyme replacement therapy may be highly effective at reducing clinical manifestations. In some patients, liver transplantation may abolish biochemical abnormalities.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

A glycogen storage disease (GSD) is the result of an enzyme defect. These enzymes normally catalyze reactions that ultimately convert glycogen compounds to monosaccharides, of which glucose is the predominant component. Enzyme deficiency results in glycogen accumulation in tissues. In many cases, the defect has systemic consequences; however, in some cases, the defect is limited to specific tissues. Most patients experience muscle symptoms, such as weakness and cramps, although certain GSDs manifest as specific syndromes, such as hypoglycemic seizures or cardiomegaly.

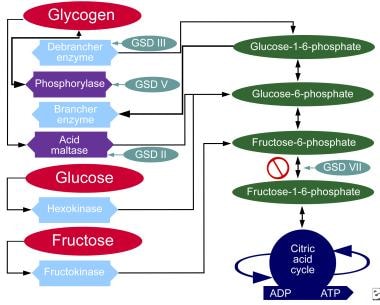

Although at least 14 unique GSDs are discussed in the literature, the 4 that cause clinically significant muscle weakness are Pompe disease (GSD type II, acid maltase deficiency), Cori disease (GSD type III, debranching enzyme deficiency), McArdle disease (GSD type V, myophosphorylase deficiency), and Tarui disease (GSD type VII, phosphofructokinase deficiency). One form, Von Gierke disease (GSD type Ia, glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency), causes clinically significant end-organ disease with significant morbidity. The remaining GSDs are not benign but are less clinically significant; therefore, the physician should consider the aforementioned GSDs when initially entertaining the diagnosis of a GSD. Interestingly, a GSD type 0 also exists and is due to defective glycogen synthase.

The chart below demonstrates where various forms of GSD affect the metabolic carbohydrate pathways.

The following list contains a quick reference for 8 of the GSD types:

-

0 - Glycogen synthase deficiency

-

Ia - Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency (von Gierke disease)

-

II - Acid maltase deficiency (Pompe disease)

-

III - Debranching enzyme deficiency (Forbes-Cori disease)

-

IV - Transglucosidase deficiency (Andersen disease, amylopectinosis)

-

V - Myophosphorylase deficiency (McArdle disease)

-

VI - Phosphorylase deficiency (Hers disease)

-

VII - Phosphofructokinase deficiency (Tarui disease)

These inherited enzyme defects usually manifest in childhood, although some, such as McArdle disease and Pompe disease, have separate adult-onset forms. In general, GSDs are inherited as autosomal recessive conditions. Several different mutations have been reported for each disorder.

Unfortunately, no cure exists, although diet therapy and enzyme replacement therapy may be highly effective at reducing clinical manifestations. In some patients, liver transplantation may abolish biochemical abnormalities. Active research continues.

Diagnosis depends on muscle biopsy, electromyelography, the ischemic forearm test, creatine kinase levels, patient history, and physical examination findings. Biochemical assay for enzyme activity is the method of definitive diagnosis. [1]

Acid maltase catalyzes the hydrogenation reaction of maltose to glucose. Acid maltase deficiency is a unique glycogenosis in that the glycogen accumulation is lysosomal rather than in the cytoplasm. It also has a unique clinical presentation depending on age at onset, ranging from fatal hypotonia and cardiomegaly in the neonate to muscular dystrophy in adults.

Pompe disease represents about 15% of all GSDs based on combined European and American data. [2]

Pathophysiology

With an enzyme defect, carbohydrate metabolic pathways are blocked, and excess glycogen accumulates in affected tissues. Each GSD represents a specific enzyme defect, and each enzyme is either in specific sites or is in most body tissues.

Acid maltase is a lysosomal enzyme that catalyzes the hydrogenation of branched glycogen compounds, notably maltose, to glucose. The conversion generally is a one-way reaction from glycogen to glucose-6-phosphate. When acid maltase is deficient, glycogen accumulates within tissues. Acid maltase is found in all tissues, including skeletal and cardiac muscle. Accumulation of glycogen in cardiac muscle leads to cardiac failure in the infantile form. [3]

In 1999, Bijvoet, Van Hirtum, and Vermey reported glycogen accumulation in murine blood vessel smooth muscle and in the respiratory, urogenital, and gastrointestinal tracts. [4] Glycogen accumulation is mostly within the lysosomes, although cytoplasmic accumulation may occur.

Infantile and adult forms are inherited as autosomal recessive conditions, traced to chromosome 17. Gort and colleagues have described nine novel mutations. [5]

Glycogen accumulation within the muscle, peripheral nerves, and the anterior horn cells results in significant weakness. In the infantile form, accumulation may also occur in the liver, which results in hepatomegaly and elevation of hepatic enzymes.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In a 1998 report on a random selection of healthy individuals to determine carrier frequency in New York, Martiniuk and colleagues extrapolated data for African Americans, revealing a frequency of 1 in 14,000-40,000 individuals. [6]

International statistics

Herling and colleagues studied the incidence and frequency of inherited metabolic conditions in British Columbia. GSDs are found in 2.3 children per 100,000 births per year. In southern China and Taiwan, infantile Pompe disease is the most common GSD with a frequency of 1 in 50,000 live births. Data from screening 3000 Dutch newborns with the previously described mutations revealed a calculated frequency of 1 in 40,000 for adult-onset disease.

Sex- and age-related demographics

Males and females are affected with equal frequency because of autosomal recessive inheritance.

In general, GSDs manifest in childhood. Later onset correlates with a less severe form. Some authors make a distinction between infant and childhood disease, although most investigators recognize a disease continuum because of the overlap of clinical manifestations.

Because both infantile and adult forms of Pompe disease occur, it should be considered if the onset is in infancy. The classic infantile form manifests with hypotonia hours to weeks after birth, with typical presentation between 4 and 8 weeks.

In non-classic infantile-onset Pompe disease, a person has inherited GAA copies that produce very little or no working acid alpha-glucosidase. It usually is less severe compared with the classic infantile-onset Pompe disease. It typically appears within the first year of the child's life but later than the classic subtype, which manifests within the first few months.

The adult form emerges as skeletal and respiratory muscle weakness in patients aged 20-40 years.

Prognosis

The adult form is not necessarily fatal, but complications such as aneurysmal rupture or respiratory failure may cause significant morbidity or mortality.

Although the infantile form typically is fatal, newer research offers promise. [7, 8] Sun and colleagues report treatment with a muscle-targeting adeno-associated virus vector in knockout mice resulted in persistent correction of muscle glycogen content. Mah and colleagues report sustained levels of correction of both skeletal and cardiac muscle glycogen with recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in a mouse model. [9]

Morbidity/mortality

The infantile form usually is fatal, with most deaths occurring within 1 year of birth. Cardiomegaly with progressive obstruction to left ventricular outflow is a major cause of mortality. Weakness of ventilatory muscles increases risk of pneumonia. Later clinical onset usually corresponds with more benign symptoms and disease course. Newer research holds promise for gene therapy.

The adult form manifests with dystrophy and respiratory muscle weakness. Respiratory insufficiency is a significant morbidity.

Glycogen deposition within blood vessels may result in intracranial aneurysm. Significant morbidity or mortality depends on location and clinical nature.

Complications

Without treatment, infants with Pompe disease can die usually owing to cardiorespiratory failure due to cardiomegaly or congestive cardiac failure within the first 2 years of life.

As Pompe disease is associated with progressive weakness of mainly the proximal muscles, and varying degrees of respiratory weakness due to dysfunction of the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles, affected individuals may become wheelchair dependent, and some may require support by mechanical ventilation.

The para-spinal muscles and neck are usually affected, which can cause scoliosis.

Patient Education

The following recommendations can be made to the patient to improve outcomes:

-

Contracture and deformity can be prevented with the use of gentle forces to counteract deforming forces. These include correction of positioning; daily stretching; provision of adequate support, especially sitting and supported standing as appropriate; and use of splinting. Orthotic intervention can help change the position and relieve pressure in those individuals who cannot do so independently. To guide successful prevention, careful consideration must be given to the number of hours per day that a muscle is in the shortened position. Surgery can be done when needed.

-

Augmentative communication, including signing and the use of assistive technology, such as voice output systems, can be used to function. It allows for conservation of energy and can also compensate for weakness and reduced endurance.

-

Advise patients to seek medical attention even for common symptoms such as fever and cough, as they can indicate a more serious underlying condition. Patients must also be advised to use over-the-counter medications carefully to treat upper respiratory tract symptoms, as they often contain sympathomimetic agents, which can be detrimental to the heart.

-

Recommend to patients that they follow strict hygiene methods at all times.

-

Encourage social interaction and encourage family education about the disease as well as methods to improve outcomes.

-

Glycogen storage disease, type II. Metabolic pathways of carbohydrates.