Practice Essentials

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can result from increased production, impaired conjugation, or impaired hepatic uptake of bilirubin, a yellow bile pigment produced from hemoglobin during erythrocyte destruction. [1, 2] It can also occur naturally in newborns. Unless treated vigorously, most patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1, a form of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, die in early infancy.

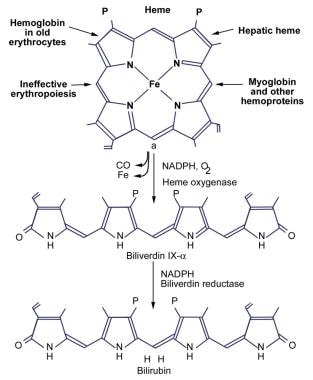

The image below illustrates the production of bilirubin.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia include the following:

-

Ineffective erythropoiesis (early labeled bilirubin [ELB] production): Characterized by the onset of asymptomatic jaundice

-

Crigler-Najjar (CN) syndrome type 1: Jaundice develops in the first few days of life and rapidly progresses by the second week; patients may present with evidence of kernicterus, the clinical manifestations of which are hypotonia, deafness, oculomotor palsy, lethargy and, ultimately, death

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2: Usually, no clinical symptoms are reported with this disease entity except for the presence of jaundice

-

Gilbert syndrome: May manifest only as jaundice on clinical examination; at least 30% of patients with Gilbert syndrome are asymptomatic, although nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal cramps, fatigue, and malaise, are common

-

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (also referred to as physiologic jaundice): Clinically obvious in 50% of neonates during the first 5 days of life

-

Pathologic neonatal jaundice: Maternal serum jaundice, also known as Lucey-Driscoll syndrome, is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder affecting the enzymes involved in bilirubin metabolism; it causes a transient familial neonatal unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, and jaundice occurs during the first 4 days of life

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1

Except for the presence of high serum unconjugated bilirubin levels, the results of liver tests in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 are normal. Serum bilirubin levels range from 20-50 mg/dL. Conjugated bilirubin is absent from serum, and bilirubin is not present in urine. Definitive diagnosis of Crigler-Najjar syndrome requires high-performance liquid chromatography of bile or a tissue enzyme assay of a liver biopsy sample.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 results in lower bilirubin concentrations than does type I, with levels ranging from 7-20 mg/dL.

Gilbert syndrome

As a rule, Gilbert syndrome can be diagnosed by a thorough history and physical examination and confirmed by standard blood tests. Laboratory results include the following:

-

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (< 4 mg/dL) noted on several occasions

-

Normal results of complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, and blood smear

-

Normal liver function test (LFT) results

-

An absence of other disease processes

Genetic testing can confirm, but is not required for a definitive diagnosis. Specialized tests that can support the diagnosis have occasionally been used. There is no role for percutaneous liver biopsy in the diagnosis of Gilbert syndrome.

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

In this physiological phenomenon, the peak total serum bilirubin level is 5-6 mg/dL (86-103 µmol/L), occurs at 48-120 hours of age, and does not exceed 17-18 mg/dL (291-308 µmol/L).

Breast milk jaundice

In breast milk jaundice, the bilirubin may increase to levels as high as 20 mg/dL, necessitating the need for phototherapy and the discontinuation of breastfeeding.

Ineffective erythropoiesis

This is characterized by a marked increase in fecal urobilinogen excretion and a normal or near-normal red blood cell lifespan.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1

-

Repeated exchange transfusions

-

Long-term phototherapy

-

Plasmapheresis

-

Hemoperfusion

-

Liver transplantation: The only guaranteed form of therapy

-

Hepatocyte transplantation

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2

Patients with this disease may not require any treatment or can be managed with phenobarbital.

Gilbert syndrome

In light of the benign and inconsequential nature of Gilbert syndrome, the use of medications to treat patients with this condition is unjustified in clinical practice.

Neonatal jaundice

No treatment is needed for benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. For breast milk jaundice and other types of nonphysiologic jaundice, phototherapy can be used.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can result from an increased production, impaired conjugation, or impaired hepatic uptake of bilirubin, a yellow bile pigment produced from hemoglobin during erythrocyte destruction. It can also occur naturally in newborns. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

Biochemistry of bilirubin

Bilirubin is a potentially toxic catabolic product of heme metabolism. There are elaborate physiologic mechanisms for its detoxification and disposition. Understanding these mechanisms is necessary for the interpretation of the clinical significance of high serum bilirubin concentrations. (See Pathophysiology and Prognosis.)

In adults, 250-400 mg of bilirubin is produced daily. Approximately 70-80% of daily bilirubin is derived from the degradation of the heme moiety of hemoglobin. The remaining 20-25% is derived from the hepatic turnover of heme proteins, such as myoglobin, cytochromes, and catalase. A small portion of daily bilirubin is derived from the destruction of young or developing erythroid cells.

Bilirubin is poorly soluble in water at physiologic pH because of the internal hydrogen bonding that engages all polar groups and gives the molecule an involuted structure. The fully hydrogen-bonded structure of bilirubin is designated bilirubin IX-alpha-ZZ. The intramolecular hydrogen bonding shields the hydrophilic sites of the bilirubin molecule, resulting in a hydrophobic structure. Water-insoluble, unconjugated bilirubin is associated with all the known toxic effects of bilirubin. Thus, the internal hydrogen bonding is critical in producing bilirubin toxicity and also prevents its elimination.

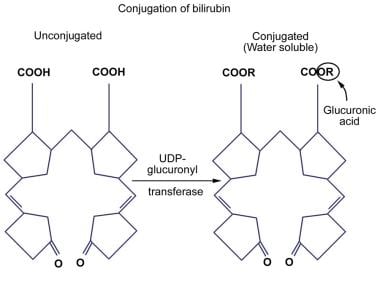

Conversion of bilirubin IX-alpha to a water-soluble form by disruption of the hydrogen bonds is essential for its elimination by the liver and kidney. This is achieved by glucuronic acid conjugation of the propionic acid side chains of bilirubin. Bilirubin glucuronides are water-soluble and are readily excreted in bile. Bilirubin is primarily excreted in normal human bile as diglucuronide; unconjugated bilirubin accounts for only 1-4% of pigments in normal bile. See the images below.

Increased production of bilirubin

Hemolysis generally induces a modest elevation in the plasma levels of unconjugated bilirubin (1-4 mg/dL). During acute hemolytic crises, such as those occurring in sickle cell disease or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, bilirubin production and plasma bilirubin may transiently exceed these levels. Although the plasma bilirubin level increases linearly in relation to bilirubin production, the bilirubin concentration may still be near the reference range in patients with a 50% reduction in red blood cell survival if hepatic bilirubin clearance is within the reference range.

Ineffective erythropoiesis (early labeled bilirubin [ELB] production) that is markedly increased is the basis of a rare disorder known as primary shunt hyperbilirubinemia, or idiopathic dyserythropoietic jaundice.

Impaired hepatic bilirubin uptake

The hepatic uptake of bilirubin can be reduced by the following:

-

Congestive heart failure

-

Surgical/naturally occurring shunts

-

Drugs/contrast agents

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia due to drugs/contrast agents resolves within 48 hours of discontinuing the drug; agents that can cause the condition include rifampicin, rifamycin, probenecid, flavaspidic acid, and bunamiodyl (cholecystographic agent).

Impaired conjugation of bilirubin

The following inherited defects of bilirubin conjugation are known to exist in humans:

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome types 1 and 2

-

Gilbert syndrome

Gilbert syndrome is believed to affect approximately 3-10% of the adult population. [5] Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a much rarer disorder, with only a few hundred cases described in the literature. (See Epidemiology.)

Crigler-Najjar syndrome

First described by Crigler and Najjar in 1952, Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a congenital, familial, nonhemolytic jaundice associated with high levels of unconjugated bilirubin. The original report described 6 infants from 3 related families with severe unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, which was recognized shortly after birth. (See Prognosis.)

Five of the children died by the age of 15 months of kernicterus, a potentially fatal disorder affecting the basal ganglia and other parts of the central nervous system. The remaining patient died at age 15 years, several months after suffering a devastating brain injury. [6] (Activation of astrocytes by unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is believed to play a major part in kernicterus via the production of inflammatory cytokines. [7] )

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a rare disorder caused by an impairment of bilirubin metabolism resulting in a deficiency or complete absence of hepatic microsomal bilirubin-uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (bilirubin-UGT) activity. [8] (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

Two distinct forms of Crigler-Najjar syndrome are as follows:

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1: Associated with neonatal unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (high levels) and kernicterus

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 (also called Arias syndrome): Presents with a lower serum bilirubin level; responds to phenobarbital treatment

Type 1 is an autosomal recessive disorder, while the mode of inheritance for Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is still not clear. Autosomal dominant transmission with variable penetrance and autosomal recessive transmission have both been reported for type 2.

Over the past decades, progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Phototherapy was long recognized as a form of treatment, [9] and in 1986, liver transplantation was shown to be curative. [10] In 1992, the locus of the missing gene behind this disorder was identified. (See Presentation, Workup, Treatment, and Medication.) [11, 12]

Gilbert syndrome

Gilbert syndrome is a benign, familial disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern characterized by intermittent jaundice in the absence of hemolysis or an underlying liver disease. The condition is recognized to arise from a mutation in the promoter region of the UGT1A1 gene, which results in reduced UGT production. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

Also called constitutional hepatic dysfunction or familial nonhemolytic jaundice, Gilbert syndrome is the mildest form of inherited, nonhemolytic unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. [13] The most common inherited cause of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, it occurs in 3-7% of the world’s population. (See Epidemiology.)

By definition, bilirubin levels in Gilbert syndrome are lower than 6 mg/dL, though most patients exhibit levels lower than 3 mg/dL. Considerable daily and seasonal variations are observed, and in as many as one third of patients, the bilirubin levels may occasionally be normal.

Gilbert syndrome may be precipitated by dehydration, fasting, menstrual periods, or other causes of stress, such as an intercurrent illness or vigorous exercise. Patients may report vague abdominal discomfort and general fatigue for which no cause is found. These episodes typically resolve spontaneously without curative treatment.

As a rule, Gilbert syndrome can be diagnosed with a thorough history and physical examination and can be confirmed with standard blood tests. Repeated investigations and invasive procedures are not usually justified for establishing a diagnosis. (See Presentation and Workup.)

Once the diagnosis of Gilbert syndrome is established, the most important aspect of treatment is reassurance. In light of the benign and inconsequential nature of the syndrome, the use of medications to treat patients with this condition is unjustified in clinical practice. (See Treatment and Medication.)

Neonatal jaundice

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

All newborns have higher bilirubin levels (mainly unconjugated bilirubin) than do adults.

Pathologic jaundice

This includes breast milk jaundice, also known as maternal milk jaundice (breastfed infants have higher mean bilirubin levels than do formula-fed infants), [14] and maternal serum jaundice, also known as Lucey-Driscoll syndrome.

ABO/Rh incompatibility

Neonatal jaundice can also result from an increased bilirubin load or from ABO/Rh incompatibility. ABO/Rh incompatibility can have the following causes:

-

Inherited red blood cell disorders: Sickle cell disease and hereditary spherocytosis/elliptocytosis

-

Drug reactions

-

Ineffective erythropoiesis: Thalassemia, vitamin B-12 deficiency, and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia

Pathophysiology

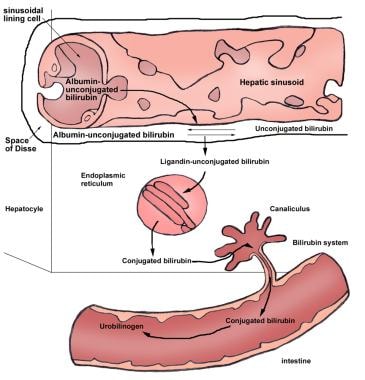

Unconjugated bilirubin is transported in the plasma bound to albumin. At the sinusoidal surface of the liver, unconjugated bilirubin detaches from albumin and is transported through the hepatocyte membrane by facilitated diffusion. Within the hepatocyte, bilirubin is bound to two major intracellular proteins: cytosolic Y protein (ie, ligandin or glutathione S-transferase B) and cytosolic Z protein (also known as fatty acid–binding protein [FABP]). The binding of bilirubin to these proteins decreases the efflux of bilirubin back into the plasma and, therefore, increases net bilirubin uptake. (See the image below.)

In order for bilirubin to be excreted into bile and, therefore, eliminated from the body, it must be made more soluble. This water-soluble, or conjugated, form of bilirubin is produced when glucuronic acid enzymatically is attached to one or both of the propionic side chains of bilirubin IX-alpha (ZZ). Enzyme-catalyzed glucuronidation is one of the most important detoxification mechanisms of the body. Of the various isoforms of the UGT family of enzymes, only one of them, bilirubin-UGT1A1, is physiologically important in bilirubin glucuronidation.

UGT enzymes are normally concentrated in the lipid bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum of the hepatocytes, intestinal cells, kidneys, and other tissues.

Attachment of glucuronic acid to bilirubin occurs through an ester linkage and, therefore, is called esterification. This esterification is catalyzed by bilirubin-UGT, which is located in the endoplasmic reticulum of the hepatocyte. This reaction leads to the production of water-soluble bilirubin monoglucuronide and bilirubin diglucuronide. Other compounds, such as xylose and glucose, also can undergo esterification with bilirubin.

Bilirubin diglucuronide is the predominant pigment in healthy adult human bile, representing over 80% of the pigment. However, in subjects with reduced bilirubin-UGT activity, the proportion of bilirubin diglucuronide decreases, and bilirubin monoglucuronide may constitute more than 30% of the conjugates excreted in bile.

Increased production of bilirubin

In a review of 11 cases of ineffective erythropoiesis (early labeled bilirubin [ELB] production), evidence existed of rapid heme and hemoglobin turnover in the bone marrow, possibly due to the premature destruction of red blood cell precursors. These patients also had erythroid hyperplasia of bone marrow, reticulocytosis, increased iron turnover with diminished red blood cell incorporation, and hemosiderosis of hepatic parenchymal cells and Kupffer cells. The underlying defect responsible for the high rate of heme turnover within the bone marrow remains unknown.

Neonatal jaundice

Hyperbilirubinemia may reach or exceed 10 mg/dL in approximately 16% of newborns. In a study of genetic risk factors in 35 breastfed term infants with prolonged unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, Chang et al found that 29 of the infants had one or more UGT1A1 mutations, with variation at nucleotide 211 being the most common. [15] Moreover, a significantly higher percentage of these neonates possessed the variant nucleotide 211 than did the control group (n=90). The authors also found that the risk of prolonged hyperbilirubinemia was higher in the male infants than in the female neonates.

In a study involving 126 Indian infants with hyperbilirubinemia, de Silva et al found an association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of both the UGT1A1 and OATP2 genes and altered bilirubin metabolism, suggesting these polymorphisms may be possible risk factors for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. [16]

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (physiologic jaundice) is a mild unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia that affects nearly all newborns and resolves within the first several weeks after birth. It has been shown that bilirubin production in a term newborn is 2-3 times higher than in adults. It is caused by increased bilirubin production, decreased bilirubin clearance, and increased enterohepatic circulation. The following factors contribute to the development of physiologic jaundice:

-

Inefficient hepatic excretion of unconjugated bilirubin

-

Portal venous shunting through a patent ductus venosus

-

Shortened red blood cell survival

-

Immaturity of hepatic bilirubin clearance: Bilirubin-UGT activity is only 1% of normal adult levels at birth, regardless of gestational age; enzyme activity increases to adult levels by the 14th week of life; the main precipitant factors are decreased energy intake and delayed closure of the ductus venosus

-

Hydrolysis of conjugated bilirubin: The activity of beta-glucuronidase is increased in newborns, which leads to greater hydrolysis of conjugated bilirubin to the unconjugated form; the unconjugated bilirubin is reabsorbed from the intestine through the process of enterohepatic circulation

-

Low bacterial degradation of bilirubin: In neonates, the bacterial degradation of bilirubin is reduced because the intestinal flora is not fully developed; this may lead to increased absorption of unconjugated bilirubin [17]

Bilirubin and drug metabolism in neonates can also be affected by the influences of ethnicity on UGT1A1 haplotype mutations. [18] A cohort study of 241 consecutive term Asian infants reported that not only was there a variance in the prevalence of hypomorphic haplotypes, but also that the frequency varied between the different races. [19] For example, Indian neonates were more likely to have at least one hydromorphic haplotype (64%) than were Chinese (48%) and Malay (31%) neonates. There was also a trend between the number of G71R mutations and the need for phototherapy.

The peak total serum bilirubin level in physiologic jaundice typically is 5-6 mg/dL (86-103 µmol/L), occurs 48-120 hours after birth, and does not exceed 17-18 mg/dL (291-308 µmol/L). Higher levels of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia are pathologic and occur in various conditions.

Nonphysiologic jaundice

Breast milk (maternal milk) jaundice results from increased enterohepatic circulation. It is thought to result from an unidentified component of human milk that enhances the intestinal absorption of bilirubin. One possible mechanism for hyperbilirubinemia in breastfed infants is the increased concentration of beta-glucuronidase in breast milk. Beta-glucuronidase deconjugates intestinal bilirubin, increasing its ability to be absorbed (ie, increasing the enterohepatic circulation).

Maternal serum jaundice (Lucey-Driscoll syndrome) may result from the presence of an unidentified inhibitor of UGT, which enters the fetus through maternal serum.

Impaired conjugation of bilirubin

Deficiency of bilirubin-UGT leads to an ineffective esterification of bilirubin, which in turn results in an unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Reduced bilirubin conjugation as a result of decreased or absent UGT activity is found in several acquired conditions and inherited diseases, such as Crigler-Najjar syndrome (types I and II) and Gilbert syndrome. Bilirubin conjugating activity is also very low in the neonatal liver. An illustration of bilirubin conjugation is shown in the image below.

UGT activity toward bilirubin is modulated by various hormones. Excess thyroid hormone and ethinyl estradiol, but not other oral contraceptives, inhibit bilirubin glucuronidation. In comparison, the combination of progestational and estrogenic steroids results in increased enzyme activity.

Bilirubin glucuronidation can also be inhibited by certain antibiotics (eg, novobiocin or gentamicin at serum concentrations exceeding therapeutic levels) and by chronic hepatitis, [20] advanced cirrhosis, and Wilson disease. [21]

Crigler-Najjar syndrome

One or more mutations in any one or more of the five exons of the gene that codes for UGT 1A1 can cause Crigler-Najjar syndrome. [22, 23, 24, 25] More than 50 mutations that cause Gilbert syndrome and Crigler-Najjar syndrome have been identified, most of which are missense or nonsense mutations.

Depending on the severity of a mutation’s effect on the enzymatic activity, Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (a complete absence of enzymatic activity) or Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 (UGT level < 10% of normal) may result. The differentiation between type 1 and 2 is not always easy, and both types are quite possibly different expressions of a single disease.

Gilbert syndrome

Hepatic bilirubin UGT activity is consistently decreased to approximately 30% of normal in individuals with Gilbert syndrome. Decreased bilirubin-UGT activity has been attributed to an expansion of thymine-adenine (TA) repeats in the promoter region of the UGT-1TA gene. Racial variations in the number of TA repeats and a correlation with enzyme activity suggest that these polymorphisms contribute to the variations in bilirubin metabolism. An increased proportion of the bilirubin monoconjugates in bile reflects reduced transferase activity. [15, 26, 27, 28]

Fasting, febrile illness, alcohol, or exercise can exacerbate jaundice in patients with Gilbert syndrome. Hemolysis and mild icterus usually occur at times of stress, starvation, and infection.

Investigators have discovered that Gilbert syndrome may coexist with other liver diseases, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Therefore, unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in patients with these other conditions may be due to Gilbert syndrome and should not always be attributed to the underlying liver disorder.

UGT mutations in Gilbert syndrome

Bilirubin-UGT, which is located primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes, is responsible for conjugating bilirubin into bilirubin monoglucuronides and diglucuronides. It is one of several UGT enzyme isoforms responsible for the conjugation of a wide array of substrates, including carcinogens, drugs, hormones, and neurotransmitters.

Knowledge of these enzymes has been enhanced greatly by the characterization of the UGT1 gene locus in humans. The gene that expresses bilirubin-UGT has a complex structure and is located on chromosome 2. [26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] There are five exons, of which exons 2-5, at the 3' end, are constant components of all isoforms of UGT, coding for the uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronic acid binding site. Exon 1 encodes for a unique region within each UGT and confers substrate specificity; exon 1a encodes the variable region for bilirubin UGT1A1. Defects in the UGT1A1 enzyme are responsible for Gilbert syndrome and for Crigler-Najjar syndrome. [35, 36]

Expression of UGT1A1 depends on a promoter region in a 5' position relative to each exon 1 that contains a TATAA box. Impaired bilirubin glucuronidation therefore may result from mutations in exon 1a, its promoter, or the common exons.

A breakthrough in understanding the genetic basis of Gilbert syndrome was achieved in 1995, when abnormalities in the TATAA region of the promoter were identified. The addition of 2 extra bases (TA) in the TATAA region interferes with the binding of transcription factor IID and results in reduced expression of bilirubin-UGT1 (30% of normal). In the homozygous state, diminished bilirubin glucuronidation is observed, with bile containing an excess of bilirubin monoglucuronide over diglucuronide. [29, 37, 38, 39, 40]

Insertion of a homozygous TA dinucleotide in the regulatory TATA box in the UGT 1A1 gene promoter is the most common genetic defect in Gilbert syndrome. [7]

In Gilbert syndrome, the UGT1A1*28 variant reduces bilirubin conjugation by 70% and is associated with irinotecan and protease inhibitor side effects. In vivo research into the genotype, present in 76% of individuals with Gilbert syndrome, suggests that transcription and transcriptional activation of glucuronidation genes responsible for conjugation and detoxification are directly affected, leading to lower responsiveness. [34]

Additional mutations have since been identified. For example, some healthy Asian patients with Gilbert syndrome do not have mutations at the promoter level but are heterozygotes for missense mutations (Gly71Arg, Tyr486Asp, Pro364Leu) in the coding region. These individuals also have significantly higher bilirubin levels than do patients with the wild-type allele.

Whether reduced bilirubin-UGT activity results from a reduced number of enzyme molecules or from a qualitative enzyme defect is unknown. To compound this uncertainty, other factors (eg, occult hemolysis or hepatic transport abnormalities) may be involved in the clinical expression of Gilbert syndrome. For example, many individuals who are homozygous for the TATAA defect do not demonstrate unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, and many patients with reduced levels of bilirubin-UGT, as observed in some granulomatous liver diseases, do not develop hyperbilirubinemia.

Because of the high frequency of mutations in the Gilbert promoter, heterozygous carriers of Crigler-Najjar syndromes types 1 and 2 can also carry the elongated Gilbert TATAA sequence on their normal allele. Such combined defects can lead to severe hyperbilirubinemia and help to explain the finding of intermediate levels of hyperbilirubinemia in family members of patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

Gilbert syndrome can also frequently coexist with conditions associated with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, such as thalassemia [41] and glucose-6-phosphate deficiency (G6PD). [42, 43] Much of the observed unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia could be attributed to variation at the UGT 1A1 locus. [44]

Origa et al, in a study of 858 patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia, found that in individuals with a combination of thalassemia and the Gilbert syndrome genotype (TA)7/(TA)7 UGT1A1, the latter effected the prevalence of cholelithiasis and influenced the age at which the condition arose. [45] The authors suggested that in patients with a combination of thalassemia and Gilbert syndrome, biliary ultrasonography should be performed, starting in childhood.

A Greek study of 198 adult patients with cholelithiasis, along with 152 controls, also found evidence of an association between Gilbert syndrome and the development of cholelithiasis. [46]

Etiology

Increased bilirubin production can result from the following:

-

Hemolysis

-

Dyserythropoiesis

-

Hematoma

Impaired hepatic bilirubin uptake can result from the following:

-

Congestive heart failure

-

Portosystemic shunts

-

Drugs: Rifamycin, rifampin, probenecid

Impaired bilirubin conjugation can result from the following:

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome types I and II

-

Gilbert syndrome (decreased uptake and/or conjugation)

-

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (physiologic jaundice)

-

Breast milk jaundice

-

Maternal serum jaundice

-

Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism

-

Ethinyl estradiol

-

Liver diseases: Chronic hepatitis, [20] cirrhosis, and Wilson disease

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

There have been fewer than 50 known cases of Crigler-Najjar syndrome in the United States, and only a few hundred cases have been described in the world literature. [47] In the United States, the prevalence of Gilbert syndrome is 3-7%.

Breast milk jaundice affects approximately 0.5-2.4% of live births. There is a familial incidence of 13.9%, indicating that, in some cases, a unique genetic factor may be expressed.

International occurrence

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a rare disease. The estimated incidence is 1 case per 1,000,000 births, with only several hundred people worldwide having been reported to have this disease. The syndrome is mostly encountered in communities where high rates of consanguineous marriages prevail.

The prevalence of Gilbert syndrome varies considerably around the world, depending on which diagnostic criteria are used (eg, number of bilirubin determinations, method of analysis, bilirubin levels used for diagnosis, whether the patient was fasting). Estimates of prevalence may be complicated further by molecular genetic studies of polymorphisms in the TATAA promoter region, which affect as many as 36% of Africans but only 3% of Asians.

Race-related demographics

In Gilbert syndrome, differences exist in the mutation of the UGT1A1 gene in certain ethnic groups; the TATAA element in the promoter region is the most common mutation site in the white population. For example, a strong correlation has been found between the UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and hyperbilirubinemia in Romanian patients with Gilbert syndrome. [5] In a study of 292 Romanian patients with Gilbert syndrome and 605 healthy counterparts, investigators used PCR gene amplification and found that the highest frequency of polymorphism was UGT1A1*28 (7TA), occurring in nearly 62% of the entire study group, followed by nearly 37% with the UGT1A1*1 (6TA) allele, and 0.61% and 0.72%, respectively, with the 5TA and 8TA variants. [5] Nearly 58% of the study cohort had the (TA)6/7 heterozygous genotype, followed by 32% with the homozygous (TA)7/7 genotype.

A racial variation exists in the development of neonatal jaundice. A common mutation in the UGT gene (Gly71Arg) leads to an increased incidence of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (approximately 20%) in Asians.

Obstetric obesity appears to correspond with both maternal and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, potentially via the inhibition of hepatic UGT1A1 enzyme, with the highest prevalence in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Island women. [48] Investigators found that increasing obesity and maternal obesity correlated with elevated maternal unconjugated bilirubin; maternal obesity was also associated with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, particularly in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Island women. [48]

Sex-related demographics

Gilbert syndrome is diagnosed more commonly in boys after puberty than in girls. The apparent sex difference is due to the fact that the daily bilirubin production is lower in women than in men. [49] The male-to-female ratio for Gilbert syndrome ranges from 2:1 to 7:1.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome occurs in both sexes equally, while neonatal physiologic jaundice occurs more frequently in males. [49]

Age-related demographics

The age at which symptoms of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia appear varies as follows:

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1: Symptoms appear within the first few days of life [50]

-

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2: Symptoms may present later than they do in type 1; patients have jaundice during the first few years of life.

-

Gilbert syndrome: This is usually diagnosed around puberty, possibly because of the inhibition of bilirubin glucuronidation by endogenous steroid hormones.

-

Benign neonatal hyperbilirubinemia affects nearly all newborns, occurs in the first 2-5 days following birth, and resolves within the first several weeks after birth.

-

Breast milk jaundice typically begins after the first 3-5 days, peaks within 2 weeks after birth, and progressively declines to normal levels over 3-12 weeks.

-

Ineffective erythropoiesis (ELB production): This condition usually emerges at age 20-30 years.

Prognosis

Neonatal jaundice

Breast milk jaundice

The prognosis in this condition is excellent. The jaundice may continue for 4 weeks but promptly resolves when breastfeeding is discontinued. Even so, the bilirubin level needs to be closely monitored, with adjustments in care made accordingly to prevent persistent hyperbilirubinemia and its potential complications (ie, kernicterus in the fragile neonatal period).

However, late neurodevelopment or hearing defects have not been observed in neonates, thus enabling the pediatrician to encourage continuation of breastfeeding in most cases of healthy infants with breast milk jaundice.

Maternal serum jaundice

The prognosis in maternal serum jaundice is good, but jaundice can persist for several weeks. This entity is occasionally associated with kernicterus.

Impaired conjugation of bilirubin

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1

Kernicterus in infancy or later in life is the main cause of death in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1. This disease can also result in permanent neurologic sequelae, due to bilirubin encephalopathy. Even with treatment, most, if not all, patients with Crigler-Najjar (CN) syndrome type 1 eventually develop some neurologic deficit.

Unless treated vigorously (ie, orthotopic liver transplant, segmental transplantation), most patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 die by age 15 months. Fortunately, more patients are surviving to adulthood because of advances in the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia.

Neonates of mothers with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 develop adverse outcomes, including developmental delay, hearing loss, and cerebellar syndrome. [51]

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2

Although the type 2 form of this disease runs a more benign clinical course than type 1, several cases of bilirubin-induced brain damage have been reported. (Bilirubin encephalopathy occurs usually when patients experience a superimposed infection or stress.) With proper treatment, however, neurologic sequelae can be avoided.

In neonates of mothers with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2, the use of phenobarbital in pregnancy appears to be safe, with good fetal and maternal outcome. [51]

Gilbert syndrome

Gilbert syndrome is a common and benign condition. The bilirubin disposition may be regarded as falling within the range of normal biologic variation. The syndrome has no deleterious associations and an excellent prognosis, and affected persons can lead a normal lifestyle. As further confirmation of its benign nature, studies have reported excellent results in patients undergoing living-donor liver transplantation from donors with Gilbert syndrome. [52, 53]

Epidemiologic studies have reported an association between Gilbert syndrome, hyperbilirubinemia, and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. [54, 55, 56] The exact mechanism for this finding is unclear, but the antioxidant properties of bilirubin may be contributory in conjunction with heme oxygenase. [57, 58, 59] (See the image below.) Moreover, mildly elevated unconjugated bilirubin appears to be associated with reduced platelet activation-related thrombogenesis and inflammation in patients with Gilbert syndrome, which may play a role in protecting these individuals from cardiovascular mortality. [56]

Clinicians need to be aware that patients with Gilbert syndrome may be at higher risk of developing toxicity from certain medications (eg, irinotecan) and protease inhibitors (eg, atazanavir, [60, 61] indinavir) that can inhibit UGT metabolism. [62] A study by Lankisch et al reported that the risk of severe hyperbilirubinemia with indinavir was associated with genetic variants of UGT1A3 and UGT1A7 genes in addition to Gilbert syndrome (UGT1A1*28). [63]

Kweekel et al reported that patients who were more likely to develop the side effects of irinotecan toxicity, such as life-threatening neutropenia and diarrhea, were more likely to have an underlying liver disease, hepatic conjugation disorders, or UGT1A1*28 genotype. [64] However, due to a lack of prospective data, the relationship between the UGT1A1 genotype and irinotecan toxicity remains unclear, although the irinotecan product label recommends reducing the irinotecan dose in patients with this genotype.

Increased production of bilirubin

The prognosis for ineffective erythropoiesis (ELB production) appears to be excellent. Similar to other causes of enhanced bilirubin production, however, it predisposes patients to cholelithiasis.

Patient Education

Educate patients and families about the chronicity of the disease and the need for lifelong treatment. Instruct them to immediately report any change in the patient's mental or neurologic status.

Genetic counseling is recommended for prospective parents with a family history of Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

-

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia. Production of bilirubin.

-

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia. Enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin.

-

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia. Conjugation of bilirubin.