Background

Atrophic gastritis is a histopathologic entity characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa with loss of the gastric glandular cells and replacement by intestinal-type epithelium, pyloric-type glands, and fibrous tissue. [1] Atrophy of the gastric mucosa is the endpoint of chronic processes, such as chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, other unidentified environmental factors, and autoimmunity directed against gastric glandular cells. [1] See the images below.

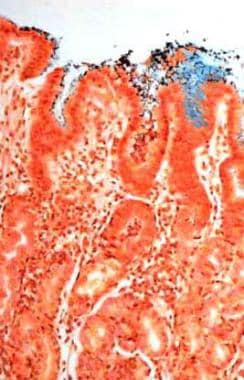

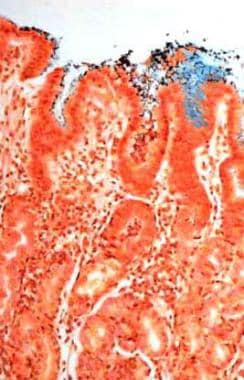

Atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis (Genta stain, 20x). Multiple organisms (brown) are observed adhering to gastric surface epithelial cells. A mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate is observed in the mucosa.

Atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis (Genta stain, 20x). Multiple organisms (brown) are observed adhering to gastric surface epithelial cells. A mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate is observed in the mucosa.

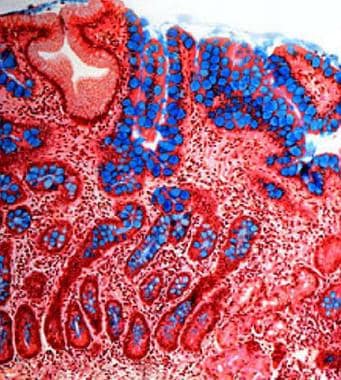

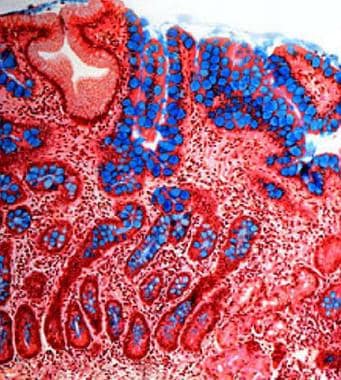

Atrophic gastritis. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa (Genta stain, 20x). Intestinal-type epithelium with numerous goblet cells (stained blue with the Alcian blue stain) replace the gastric mucosa and represent gastric atrophy. Mild chronic inflammation is observed in the lamina propria. This pattern of atrophy is observed both in Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis and autoimmune gastritis.

Atrophic gastritis. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa (Genta stain, 20x). Intestinal-type epithelium with numerous goblet cells (stained blue with the Alcian blue stain) replace the gastric mucosa and represent gastric atrophy. Mild chronic inflammation is observed in the lamina propria. This pattern of atrophy is observed both in Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis and autoimmune gastritis.

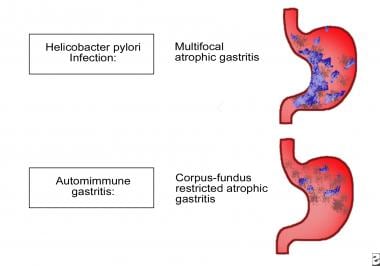

The 2 main causes of atrophic gastritis result in distinct topographic types of gastritis, which can be distinguished histologically. H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis is usually a multifocal process that involves both the antrum and the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric corpus and fundus, whereas autoimmune gastritis essentially is restricted to the gastric corpus and fundus. Individuals with autoimmune gastritis [2] may develop pernicious anemia because of extensive loss of parietal cell mass and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies.

H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis is frequently asymptomatic, but individuals with this disease are at increased risk of developing gastric carcinoma, which may decrease following H pylori eradication. [3] Patients with chronic atrophic gastritis develop low gastric acid output and hypergastrinemia, which may lead to enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia and carcinoid tumors. [4]

For patient education resources, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Gastritis.

Pathophysiology

H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis

H pylori are gram-negative bacteria that colonize and infect the stomach. The bacteria lodge within the mucous layer of the stomach along the gastric surface epithelium and the upper portions of the gastric foveolae and rarely are present in the deeper glands (see the 3 images below).

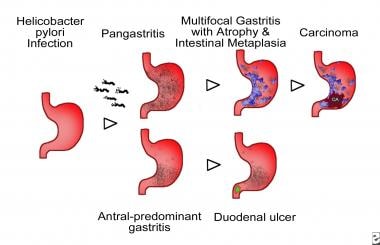

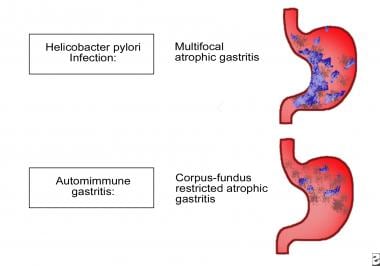

Atrophic gastritis. Schematic representation of Helicobacter pylori–associated patterns of gastritis. Involvement of the corpus, fundus, and gastric antrum, with progressive development of gastric atrophy as a result of the loss of gastric glands and partial replacement of gastric glands by intestinal-type epithelium, or intestinal metaplasia (represented by the blue areas in the diagram) characterize multifocal atrophic gastritis. Individuals who develop gastric carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually present with this pattern of gastritis. Inflammation mostly limited to the antrum characterizes antral-predominant gastritis. Individuals with peptic ulcers usually develop this pattern of gastritis, and it is the most frequent pattern in the Western countries.

Atrophic gastritis. Schematic representation of Helicobacter pylori–associated patterns of gastritis. Involvement of the corpus, fundus, and gastric antrum, with progressive development of gastric atrophy as a result of the loss of gastric glands and partial replacement of gastric glands by intestinal-type epithelium, or intestinal metaplasia (represented by the blue areas in the diagram) characterize multifocal atrophic gastritis. Individuals who develop gastric carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually present with this pattern of gastritis. Inflammation mostly limited to the antrum characterizes antral-predominant gastritis. Individuals with peptic ulcers usually develop this pattern of gastritis, and it is the most frequent pattern in the Western countries.

Patterns of atrophic gastritis associated with chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis.

Patterns of atrophic gastritis associated with chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis.

Atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis (Genta stain, 20x). Multiple organisms (brown) are observed adhering to gastric surface epithelial cells. A mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate is observed in the mucosa.

Atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis (Genta stain, 20x). Multiple organisms (brown) are observed adhering to gastric surface epithelial cells. A mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate is observed in the mucosa.

The infection is usually acquired during childhood and progresses over the lifespan of the individual if left untreated. The host response to the presence of H pylori is composed of a T-lymphocytic and B-lymphocytic response, followed by infiltration of the lamina propria and gastric epithelium by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) that eventually phagocytize the bacteria.

Significant damage associated with the release of bacterial and inflammatory toxic products is inflicted on the gastric epithelial cells, resulting in increasing cell loss or gastric atrophy over time. Weck published a study supporting their hypothesis that the association between H pylori and chronic atrophic gastritis was greatly underestimated due to the clearance of the infection in advanced stages of the disease. [5] These results suggest that the association is much stronger than estimated by most epidemiologic studies to date. Another study also reported that mannan-binding lectin allele (MBL2 codon 54 B) is associated with a higher risk of developing more severe gastric mucosal atrophy in H pylori–infected Japanese patients. [6]

During the process of gastric mucosal atrophy, some glandular units develop an intestinal-type epithelium, and intestinal metaplasia eventually occurs in multiple foci throughout the gastric mucosa when atrophic gastritis is fully established. Other glands are simply replaced by fibrous tissue, resulting in an expanded lamina propria. [7] Loss of gastric glands in the corpus, or corpus atrophy, reduces parietal cell numbers, which results in significant functional changes with decreased levels of acid secretion and increased gastric pH. [8] Hypochloridia or achloridia raises serum gastrin levels, thereby increasing the risk for the development of neuroendocrine tumors. [8] Studies have also reported that moderate alcohol consumption may be associated with atrophic gastritis by facilitating H pylori clearance. [9]

H pylori–associated chronic gastritis progresses with 2 main topographic patterns that have different clinicopathologic consequences.

The first is antral predominant gastritis. Inflammation that is mostly limited to the antrum characterizes antral predominant gastritis. Individuals with peptic ulcers usually develop this pattern of gastritis, and it is the most frequently observed pattern in Western countries.

The second is multifocal atrophic gastritis. Involvement of the corpus, fundus, and gastric antrum with progressive development of gastric atrophy (ie, loss of gastric glands) and partial replacement of gastric glands by intestinal-type epithelium (intestinal metaplasia) characterize multifocal atrophic gastritis. Individuals who develop gastric carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually have this pattern of gastritis. This pattern is observed more often in developing countries and in Asia.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis

The development of chronic atrophic gastritis limited to corpus-fundus mucosa and marked diffuse atrophy of parietal and chief cells characterize autoimmune atrophic gastritis, as shown in the following two images.

Patterns of atrophic gastritis associated with chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis.

Patterns of atrophic gastritis associated with chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis.

Atrophic gastritis. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa (Genta stain, 20x). Intestinal-type epithelium with numerous goblet cells (stained blue with the Alcian blue stain) replace the gastric mucosa and represent gastric atrophy. Mild chronic inflammation is observed in the lamina propria. This pattern of atrophy is observed both in Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis and autoimmune gastritis.

Atrophic gastritis. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa (Genta stain, 20x). Intestinal-type epithelium with numerous goblet cells (stained blue with the Alcian blue stain) replace the gastric mucosa and represent gastric atrophy. Mild chronic inflammation is observed in the lamina propria. This pattern of atrophy is observed both in Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis and autoimmune gastritis.

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with serum antiparietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies that cause intrinsic factor (IF) deficiency, which, in turn, causes decreased availability of cobalamin (vitamin B-12) and, eventually, pernicious anemia in some patients.

Palladino reported that methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms may be associated with B12 deficiency and autoimmune atrophic gastritis. [10] Autoantibodies are directed against at least 3 antigens, including IF, cytoplasmic (microsomal-canalicular), and plasma membrane antigens. Two types of IF antibodies are detected (types I and II). Type I IF antibodies block the IF-cobalamin binding site, thus preventing the uptake of vitamin B12. Cell-mediated immunity also contributes to the disease. [11]

T-cell lymphocytes infiltrate the gastric mucosa and contribute to the epithelial cell destruction and resulting gastric atrophy. Stummvoll reported that Th17 cells induced the most destructive disease with cellular infiltrates composed primarily of eosinophils accompanied by high levels of serum IgE. [12] Polyclonal Treg also suppresses the capacity of Th1 cells and moderately suppresses Th2 cells, but it can suppress Th17-induced disease only at early time points.

The major effect of Treg was to inhibit the expansion of the effector T cells. However, effector cells isolated from protected animals were not anergic and were fully competent to proliferate and produce effector cytokines ex vivo. [12] The strong inhibitory effect of polyclonal Treg on the capacity of some types of differentiated effector cells to induce disease provides an experimental basis for the clinical use of polyclonal Treg in the treatment of autoimmune disease in humans.

The above findings led to an interesting study by Huter et al, who reported that antigen-specific-induced Treg are potent suppressors of autoimmune gastritis induced by both fully differentiated Th1 and Th17 effector cells. The investigators analyzed the suppressive capacity of different types of Treg to suppress Th1- and Th17-mediated autoimmune gastritis by comparing nTreg with polyclonal TGFbeta-induced WT Treg (iTreg) or TGFbeta-induced antigen-specific TxA23 iTreg in cotransfer experiments with Th1 or Th17 TxA23 effector T cells. [13] Th1-mediated disease was prevented by cotransfer of nTreg and also antigen-specific iTreg, whereas WT iTreg did not show an effect. However, Th17-mediated disease was only suppressed by antigen-specific iTreg. Preactivation of nTreg in vitro before the transfer did not increase their suppressive activity in Th17-mediated gastritis, supporting the investigators' hypothesis. [13]

Etiology

Atrophic gastritis usually is associated with either chronic H pylori infection or with autoimmune gastritis. The environmental subtype of atrophic gastritis corresponds mostly with H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis, although other unidentified environmental factors may play a role in the development of gastric atrophy. Yagi et al used magnifying endoscopy to distinguish atrophic gastritis caused by H pylori from autoimmune gastritis. [14]

Chronic gastritis caused by H pylori infection of the stomach

H pylori infection of the stomach is by far the most common cause of chronic atrophic gastritis.

The risk of atrophic gastritis is increased by 10-fold if an H pylori infection is present.

Whether H pylori infection follows the multifocal atrophic gastritis pathway or the nonatrophic antral gastritis pathway may be related to genetic susceptibility factors, environmental factors that modulate the host-bacterial interaction, or bacterial strains.

Although H pylori possessing the cag (cytotoxin-associated gene) pathogenicity island have been shown to have increased virulence, to cause higher levels of mucosal inflammation, and to be present more frequently in individuals infected with H pylori who develop gastric cancer, no specific virulence factors have been identified that might be useful to predict specific H pylori disease outcome.

Host factors or the effects of other environmental agents are likely to be the determinant elements modulating patterns of disease progression. For example, family relatives of individuals with gastric cancer develop pangastritis more frequently in response to H pylori infection and they also develop multifocal intestinal metaplasia more often, a preneoplastic lesion of the stomach and a component of H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is a type of chronic atrophic gastritis limited to the corpus-fundus mucosa and characterized by marked diffuse atrophy of the parietal and chief cells.

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with serum antiparietal and anti-IF antibodies that cause IF deficiency, which, in turn, causes decreased availability of cobalamin and, eventually, pernicious anemia in some patients.

In some families, the disease appears to be transmitted with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.

A large population-based study by Zhang et al suggested that the presence of antigastric parietal cell antibodies (APCAs) may contribute to the development of chronic atrophic gastritis even in the absence of H pylori infection. The study, which included 9684 persons aged 50-74 years, reported an overall seroprevalence of APCA in this population of 19.5%, with a strong association found between the existence of APCAs and the presence of chronic atrophic gastritis. The more severe the disease, the greater the association with APCA was found. However, the link between APCAs and the severity of chronic atrophic gastritis was greatest in persons who were negative for H pylori. [15]

Epidemiology

United States data

The frequency of atrophic gastritis and the prevalence of chronic atrophic gastritis is not known because chronic gastritis frequently is asymptomatic [8] ; however, prevalence of atrophic gastritis parallels the 2 main causes of gastric atrophy, chronic H pylori infection (when the infection follows a course of multifocal atrophic gastritis) and autoimmune gastritis. In both conditions, atrophic gastritis develops over many years and is found later in life. The frequency of H pylori infection in the United States is similar to that found in other Western countries. In the United States, H pylori infection affects approximately 20% of persons younger than 40 years and 50% of those older than 60 years. However, subgroups of different ethnic backgrounds show different frequencies for the infection, which is more common in Asian, Hispanic, and African American persons.

International data

An estimated 50% of the world's population is infected with H pylori, and, therefore, chronic gastritis is extremely common. H pylori infection is highly prevalent in Asia and in the developing countries, and multifocal atrophic gastritis is more prevalent in these areas of the world.

Autoimmune gastritis is a relatively rare disease, most frequently observed in individuals of northern European descent and in African Americans.

The prevalence of pernicious anemia resulting from autoimmune gastritis has been estimated as 127 cases per 100,000 members of the population in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden. The incidence of pernicious anemia is increased in patients with other immunological diseases, including Graves disease, myxedema, thyroiditis, and hypoparathyroidism.

Race-related demographics

H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis appears to be more common among Asian and Hispanic persons than people of other races.

In the United States, H pylori infection is more common among African Americans than white persons, a difference attributed to socioeconomic factors. However, whether higher rates of H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis are observed among African Americans has not been established.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis is more frequent in individuals of northern European descent and African Americans and is much less frequent in southern Europeans and Asians.

Sex-related demographics

Atrophic gastritis affects both sexes similarly, as does H pylori.

Autoimmune gastritis has been reported to affect both sexes, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1.

Age-related demographics

Atrophic gastritis is detected late in life, because it results from the effects of long-standing damage to the gastric mucosa.

H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis develops gradually, but extensive multifocal atrophy usually is detected in individuals older than 50 years.

Patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis usually present with pernicious anemia, which typically is diagnosed in individuals aged approximately 60 years; however, pernicious anemia can be detected in children (juvenile pernicious anemia).

Prognosis

Atrophic gastritis is a progressive condition with increasing loss of gastric glands and replacement by foci of intestinal metaplasia over years.

Results from studies evaluating the evolution of atrophic gastritis after eradication of H pylori have been conflicting. Follow-up for up to several years after H pylori eradication has not shown regression of gastric atrophy in most studies, whereas other studies report improvement in the extent of atrophy.

Whether H pylori eradication in a patient with atrophic gastritis reduces the risk of development of gastric cancer is another important question. Available data are limited, but a prospective study in a Japanese population reported that H pylori eradication in patients with endoscopically-resected early gastric cancer resulted in decreased appearance of new early cancers, while intestinal-type gastric cancers developed in the control group without H pylori eradication.

These findings support an interventional approach, with eradication of H pylori if the organisms are detected in patients with atrophic gastritis, aiming at prevention of development of gastric cancer.

Morbidity/mortality

Mortality and morbidity associated with atrophic gastritis are related to specific clinicopathologic complications that may develop during the course of the underlying disease.

Similar to other individuals infected with H pylori, patients who develop atrophic gastritis may complain of dyspeptic symptoms. Individuals with either H pylori–associated atrophic gastritis or autoimmune atrophic gastritis carry an increased risk of developing gastric carcinoid tumors and gastric carcinoma. More recently, there is a case report from New York Mount Sinai Hospital involving synchronous gastric neuroendocrine tumor (NET) and duodenal gastrinoma with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis in the absence of H pylori infection. [16] The patient underwent transduodenal resection of the duodenal NETs, and subsequent followup over 2 years revealed no recurrence or metastasis from the gastric or duodenal disease.

The major effects of autoimmune gastritis are consequences of the loss of parietal and chief cells and include achlorhydria, hypergastrinemia, loss of pepsin and pepsinogen, anemia, and an increased risk of gastric neoplasms.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis represents the most frequent cause of pernicious anemia in temperate climates. The risk of gastric adenocarcinoma appears to be at least 2.9 times higher in patients with pernicious anemia than in the general population. A recent study also reported an increased frequency of esophageal squamous carcinomas in patients with pernicious anemia.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and H pylori gastritis may also have a significant role in the development of unexplained or refractory iron deficient anemia.

Complications

The multifocal atrophic gastritis that develops in some individuals with H pylori infection is associated with increased risk of the following:

-

Gastric ulcers

-

Gastric adenocarcinoma

The corpus-restricted atrophic gastritis that develops in patients with autoimmune gastritis is associated with an increased risk of the following:

-

Pernicious anemia

-

Gastric polyps

-

Gastric adenocarcinoma

-

Atrophic gastritis. Schematic representation of Helicobacter pylori–associated patterns of gastritis. Involvement of the corpus, fundus, and gastric antrum, with progressive development of gastric atrophy as a result of the loss of gastric glands and partial replacement of gastric glands by intestinal-type epithelium, or intestinal metaplasia (represented by the blue areas in the diagram) characterize multifocal atrophic gastritis. Individuals who develop gastric carcinoma and gastric ulcers usually present with this pattern of gastritis. Inflammation mostly limited to the antrum characterizes antral-predominant gastritis. Individuals with peptic ulcers usually develop this pattern of gastritis, and it is the most frequent pattern in the Western countries.

-

Patterns of atrophic gastritis associated with chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune gastritis.

-

Atrophic gastritis. Helicobacter pylori–associated chronic active gastritis (Genta stain, 20x). Multiple organisms (brown) are observed adhering to gastric surface epithelial cells. A mononuclear lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate is observed in the mucosa.

-

Atrophic gastritis. Intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa (Genta stain, 20x). Intestinal-type epithelium with numerous goblet cells (stained blue with the Alcian blue stain) replace the gastric mucosa and represent gastric atrophy. Mild chronic inflammation is observed in the lamina propria. This pattern of atrophy is observed both in Helicobacter pylori–associated atrophic gastritis and autoimmune gastritis.

-

Marked gastric atrophy of the stomach body.

-

Severe gastric atrophy of the stomach antrum.