Practice Essentials

Filariasis is a disease group caused by filariae that affects humans and animals (ie, nematode parasites of the family Filariidae). [1, 2] Of the hundreds of described filarial parasites, only 8 species cause natural infections in humans. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified lymphatic filariasis as a major cause of disability worldwide, with an estimated 40 million individuals affected by the disfiguring features of the disease. [1, 3]

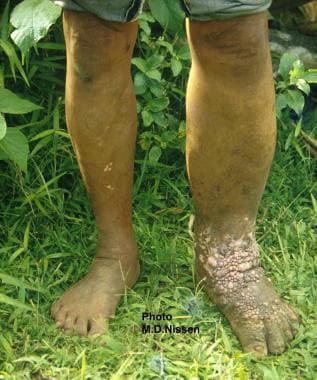

In lymphatic filariasis, repeated episodes of inflammation and lymphedema lead to lymphatic damage, chronic swelling, and elephantiasis of the legs, arms, scrotum, vulva, and breasts. [1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Filariasis. Unilateral left lower leg elephantiasis secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a boy.

Filariasis. Unilateral left lower leg elephantiasis secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a boy.

Signs and symptoms

Lymphatic filariasis

-

Fever

-

Inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy

-

Testicular and/or inguinal pain

-

Skin exfoliation

-

Limb or genital swelling - Repeated episodes of inflammation and lymphedema lead to lymphatic damage, chronic swelling, and elephantiasis of the legs, arms, scrotum, vulva, and breasts

The following acute syndromes have been described in lymphatic filariasis:

-

Acute adenolymphangitis (ADL) - Sudden fever with lymphadenopathy

-

Filarial fever - Fever without associated adenitis

-

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) - Dry nocturnal cough

Onchocerciasis

The clinical triad of infection in onchocerciasis is as follows:

-

Dermatitis - Skin lesions include edema, pruritus, erythema, papules, scablike eruptions, altered pigmentation, and lichenification

-

Skin nodules (ie, onchocercomas) - Tend to be common over bony prominences, with anatomic location depending on geographic region of transmission

-

Ocular lesions - Usually related to the duration and severity of infection and are caused by an abnormal host immune response to microfilariae; loss of visual acuity may occur

Loiasis

The diagnostic feature of loiasis is the Calabar swelling, ie, a large, transient area of localized, nonerythematous subcutaneous edema resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to the parasite. This is most common around the joints. An additional manifestation of loiasis results from migration of the parasite across the conjunctiva, causing discomfort and irritation of the eye.

Mansonelliasis

Mansonella infections are usually asymptomatic. If symptoms are present, they may include fever, pruritus, skin lumps, lymphadenitis, and abdominal pain.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Microfilariae are detectable via examination of the following:

-

Blood - The microfilariae of all species that cause lymphatic filariasis and the microfilariae of Loa loa, Mansonella ozzardi, and Mansonella perstans are detected in blood. [10] Wuchereria bancrofti can be detected via circulating filarial antigen (CFA) assays.

-

Urine - If lymphatic filariasis is suspected, urine should be examined macroscopically for chyluria and then concentrated to examine for microfilariae.

-

Skin – Onchocerca volvulus and Mansonella streptocerca infections are diagnosed when microfilariae are detected in multiple skin-snip specimens taken from different sites.

-

Eye - Microfilariae of O volvulus may be detected in the cornea or anterior chamber of the eye using slit-lamp examination.

Useful imaging studies in the evaluation of filariasis include the following:

-

Chest radiography - Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates are visible in patients with TPE

-

Ultrasonography - Can be used to demonstrate and monitor lymphatic obstruction of the inguinal and scrotal lymphatics; has been used to demonstrate the presence of viable worms

-

Lymphoscintigraphy [11]

Histologic findings include the following:

-

Lymphatic filariasis - Affected lymph nodes demonstrate fibrosis and lymphatic obstruction with the creation of collateral channels

-

Elephantiasis - The skin is characterized by hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, lymph and fatty tissue, loss of elastin fibers, and fibrosis

-

Onchocerciasis - Onchocercomas have a central stromal and granulomatous, inflammatory region where the adult worms are found and a peripheral, fibrous section; microfilariae in the skin incite a low-grade inflammatory reaction with loss of elasticity and fibrotic scarring

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Antimicrobials used in the treatment of filariasis include the following:

-

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC)

-

Ivermectin

-

Suramin

-

Mebendazole

-

Flubendazole

-

Albendazole

-

Doxycycline - Used to target Wolbachia, an endosymbiotic bacteria in multiple filarial species

Surgery

In lymphatic filariasis, large hydroceles and scrotal elephantiasis are manageable with surgical excision. Correcting gross limb elephantiasis with surgery is less successful and may necessitate multiple procedures and skin grafting.

In onchocerciasis, nodulectomy with local anesthetic is a common treatment to reduce skin and eye complications.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Filariasis is a disease group affecting humans and animals, caused by filariae; ie, nematode parasites of the family Filariidae. [2] Filarial parasites can be classified according to the habitat of the adult worms in the vertebral host, as follows:

-

Lymphatic group - Includes Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori

-

Body-cavity group - Includes M perstans and M ozzardi [12]

Of the hundreds of described filarial parasites, only 8 species cause natural infections in humans. The parasites of the cutaneous and lymphatic groups are the most clinically significant. Other species of filariae may cause incomplete infections because they are unable to reach adult maturity in human hosts and therefore cannot produce first-stage larvae, known as microfilariae (eg, Dirofilaria immitis [dog heartworm], Dirofilaria [Nochtiella] repens, and Dirofilaria tenuis [raccoon heartworm]).

See Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Workup.

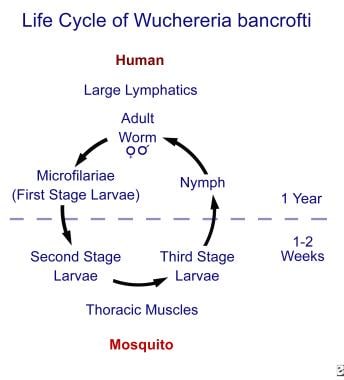

Filariasis. This figure displays the life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti in humans and mosquito vectors (ie, Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Mansonia species). Life cycles of other lymphatic nematodes (ie, Brugia malayi, Brugia timori) are identical, while the life cycles for other filariae differ in the body location of adult worms, the microfilariae present, and the arthropod intermediate hosts and vectors.

Filariasis. This figure displays the life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti in humans and mosquito vectors (ie, Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Mansonia species). Life cycles of other lymphatic nematodes (ie, Brugia malayi, Brugia timori) are identical, while the life cycles for other filariae differ in the body location of adult worms, the microfilariae present, and the arthropod intermediate hosts and vectors.

Filariasis has a significant economic and psychosocial impact in endemic areas, disfiguring and/or incapacitating more than 40 million individuals. [3] With a strong association with mental illness, depression with filariasis is believed to account for 5.09 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). [13]

See Epidemiology, Prognosis, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment for more detail.

Filariae have a specific geographic distribution. For example, W bancrofti is found in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, India, and the Pacific Islands. B malayi is found in similar locations but not in sub-Saharan Africa. B timori occurs on Timor Island, in Indonesia.

In endemic areas, the prevalence of microfilaremia increases with age, as adult worms are gradually acquired over years. Lymphatic filariasis is first contracted in childhood, and most individuals in endemic areas have been exposed by the third or fourth decade of life. [14]

See Pathophysiology and Etiology.

As with most helminths, adult filarial parasites replicate in a definitive host. The adult worm burden in an individual cannot increase unless the host is exposed to additional microfilaria. Infected individuals cannot sustain higher levels of parasitemia once they leave the endemic area.

Because the mosquito vector is inefficient, a relatively prolonged stay in an endemic area is usually required to acquire the infection. Disorganized urbanization is adding to the vector population and hence to the increased incidence and prevalence of such diseases in low-income countries.

Patient education

Patients should learn to protect against insect vectors and to refrain from self-treatment regimens, especially with diethylcarbamazine (DEC), since this drug can lead to meningoencephalopathy.

See Treatment and Medication.

Pathophysiology

The filarial life cycle, like that of all nematodes, consists of 5 developmental (larval) stages in a vertebral host and an arthropod intermediate host and vector. Adult female worms produce thousands of first-stage larvae, or microfilariae, which are ingested by a feeding insect vector. Some microfilariae have a unique daily circadian periodicity in the peripheral circulation. The arthropod vectors (mosquitoes and flies) also have a circadian rhythm in which they obtain blood meals. The highest concentration of microfilariae usually occurs when the local vector is feeding most actively. [15]

Microfilariae undergo two developmental changes in the insect. Third-stage larvae then are inoculated back into the vertebral host during the act of feeding for the final two stages of development. These larvae travel through the dermis and enter regional lymphatic vessels. During the next 9 months, the larvae develop into mature worms (20-100 mm in length). An average parasite can survive for about 5 years.

The pre-patent period is defined as the interval between a vector bite and the appearance of microfilariae in blood, with an estimated duration of about 12 months.

The following factors affect the pathogenesis of filariasis:

-

The duration and level of exposure to infective insect bites [18]

-

The number of secondary bacterial and fungal infections [16]

-

The degree of host immune response [19]

Filarial infection generates significant inflammatory immune responses that participate in the development of symptomatic lymphatic obstruction. Increased levels of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) secondary to antigenic (from dead worms) stimulation of Th2-type immune response have been demonstrated. [20]

Studies indicate that there is a familial tendency to lymphatic obstruction. This provides support for the hypothesis that host genes influence lymphedema susceptibility. [21] Studies also suggest that microfilaremia may be increased in individuals with low levels of mannose-binding lectin, suggesting a genetic predisposition. [9] Furthermore, a propensity to develop chronic disease has been demonstrated in patients with polymorphisms of endothelin-1 and tumor necrosis factor receptor II. [22]

Prenatal exposure seems to be an important determinant in conferring greater immune tolerance to parasite antigen. [23] Thus, individuals from endemic areas are often asymptomatic until late in the disease when they have high worm burden, whereas nonimmune expatriates tend to have brisk immune responses and more severe early clinical symptoms, even in light infections.

Studies have shown that lymphatic filarial parasites contain rickettsia-like Wolbachia endosymbiotic bacteria. [24] This association has been recognized as contributing to the inflammatory reaction seen in filariasis.

Etiology

Lymphatic filariasis

Mosquitoes of the genera Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, or Mansonia are the intermediate hosts and vectors of all species that cause lymphatic filariasis. [25]

Acute lymphatic filariasis is related to larval molting and adult maturation to fifth-stage larvae. Adult worms are found in lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels distal to the nodes. Females measure 80-100 mm in length and males are 40 mm.

The most commonly affected nodes are in the femoral and epitrochlear regions. Abscess formation may occur at the nodes or anywhere along the distal vessel. Infection with B timori appears to result in more abscesses than infection with B malayi or W bancrofti.

Filarial abscess scar on the left upper thigh in a young male who is positive for Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae

Filarial abscess scar on the left upper thigh in a young male who is positive for Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae

Cellular invasion with plasma cells, eosinophils, and macrophages, together with hyperplasia of the lymphatic endothelium, occurs with repeated inflammatory episodes. The consequence is lymphatic damage and chronic leakage of protein-rich lymph in the tissues, thickening and verrucous changes of the skin, and chronic streptococcal and fungal infections, all of which contribute to the appearance of elephantiasis. (The skin of individuals with elephantiasis is characterized by hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, lymph and fatty tissue, loss of elastin fibers, and fibrosis.)

B malayi elephantiasis is more likely to affect the upper and lower limbs, with genital pathology and chyluria being rare. Secondary bacterial infection in elephantiasis can result in blindness.

Occult filariasis

Occult filariasis denotes filarial infection in which microfilariae are not observed in the blood but may be found in other body fluids and/or tissues.

The occult syndromes are as follows:

-

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) - Symptoms result from allergic and inflammatory reactions elicited by the microfilariae and parasite antigens of W bancrofti or B malayi that the lungs clear from the bloodstream

-

D immitis or D repens infection - Human infection with D immitis may result in pulmonary lesions of immature Dirofilaria worms in the lung periphery; if D immitis larvae lodge in branches of the pulmonary arteries, they can cause pulmonary infarcts

-

Filarial arthritis

-

Filarial breast abscess

-

Filarial-associated immune-complex glomerulonephritis

Onchocerciasis

O volvulus microfilariae from the skin are ingested by the Simulium species of blackflies. Chronic onchocerciasis cases are hyper-responsive to parasite antigen, have increased eosinophilia, and result in the presence of high levels of serum IgE. Patterns of onchocercal eye disease also are associated with parasite strain differences at the DNA level. [26]

Loiasis

Mango flies or deerflies of Chrysops genus transmit loiasis. Response to L loa infection appears to differ between residents and nonresidents in endemic areas. Nonresidents with infection appear to be more prone to symptoms than residents despite lower levels of microfilaremia. Eosinophil, serum IgE, and antibody levels are also higher in nonresidents with infection. [27]

L loa meningoencephalopathy

Meningoencephalopathy is a severe and often fatal complication of infection. This syndrome is usually related to diethylcarbamazine (DEC) administration in individuals with high-density microfilaremia but it may occur without drug therapy. [28]

DEC causes a large influx of microfilariae into the cerebrospinal fluid, leading to capillary obstruction, cerebral edema, hypoxia, and coma. Localized necrotizing granulomas are also present, in response to microfilariae. Endomyocardial fibrosis, nephritic syndrome, and venous thrombosis also may be observed.

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

No form of human filariasis is currently endemic to the United States. W bancrofti once was prevalent in Charleston, South Carolina, because of the presence of suitable mosquito vectors. Immigrant populations and persons who have traveled long-term to the tropics are potential reservoirs of infection.

Returning missionaries and overseas workers/volunteers are at particular risk for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis, because of the long pre-patent period and relatively high intensity of exposure required between exposure to infective insect bites and the development of sexually mature adult worms.

Two cases of ocular onchocerciasis have been reported in the United States [29] as has a single case of a spinal mass in a toddler due to Onchocerca lupi infection. [30]

Global occurrence

Lymphatic filariasis affects more than 120 million people worldwide and is found throughout the tropics and subtropics. In 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated the Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) with a goal to globally eliminate lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem by 2020. [3, 31] This initiative utilizes mass drug administration (MDA) in 60 countries. The goal is to reduce prevalence levels to a point at which transmission is no longer sustainable. This program has led to a prevalence reduction in 15 countries so far. [3]

At least 37 million people are infected with O volvulus globally. The vast majority of cases (99%) occur in sub-Saharan Africa. [32] Onchocerciasis is the second leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide. Approximately half a million people are affected. [33] In 2016, Abu-Hamed, Sudan, became the first region to eliminate the disease under a mass treatment program with ivermectin. [34] Today, continued efforts to reduce disease prevalence are conducted via guidance by the WHO and the Non-Governmental Development Organizations Coordination Group for Onchocerciasis Control.

Prevalence rates of L loa range from 3-13 million people worldwide. [35] Loiasis remains of particular interest when initiating MDA programs for lymphatic filariasis because the drugs commonly used in these regimens (DEC) may have adverse effects in patients with high-density Loa loa infection.

Sex- and age-related demographics

Both sexes are equally susceptible to filariasis. Because of different local and cultural practices, however, as well as differences in exposure to insect vectors, one sex or the other may be exposed to infection more often.

Individuals of all ages are susceptible to infection and are potentially microfilaremic. Microfilaremia rates increase with age through childhood and early adulthood, although clinical infection may not be apparent. The manifestation of acute and chronic filariasis usually occurs only after years of repeated and intense exposure to infected vectors in endemic areas.

Prognosis

The prognosis in filariasis is good if infection is recognized and treated early. Filarial diseases are rarely fatal, but the consequences of infection can cause significant personal and socioeconomic hardship for those who are affected.

The morbidity of human filariasis results mainly from the host reaction to microfilariae or developing adult worms in different areas of the body. Long-term disability may result from chronic lymphatic damage or blindness, depending on the infectious filarial organism.

-

Filariasis. This figure displays the life cycle of Wuchereria bancrofti in humans and mosquito vectors (ie, Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Mansonia species). Life cycles of other lymphatic nematodes (ie, Brugia malayi, Brugia timori) are identical, while the life cycles for other filariae differ in the body location of adult worms, the microfilariae present, and the arthropod intermediate hosts and vectors.

-

Filarial abscess scar on the left upper thigh in a young male who is positive for Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae

-

Lymphatic filariasis resulting from Wuchereria bancrofti infection may result in limb lymphedema, inguinal lymphadenopathy, and hydrocele. Photograph taken by Professor Bruce McMillan and donated by John Walker, MD.

-

Filariasis. Unilateral left lower leg elephantiasis secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a boy.

-

Filariasis. This is a close-up view of the unilateral lower leg elephantiasis shown in the previous image. Note the lymphedema and typical skin appearance of depigmentation and verrucous “warts.”

-

Filariasis. Lateral view of the right outer aspect of a leg affected by elephantiasis secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection.

-

Filariasis. Inner aspect of the lower leg of the male patient in the previous image, showing gross elephantiasis secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection.

-

Filariasis. Unilateral left hydrocele and testicular enlargement secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a man who also was positive for microfilariae.

-

Filariasis. Bilateral hydrocele, testicular enlargement, and inguinal lymphadenopathy secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection.

-

Filariasis. Adult worms of Wuchereria bancrofti in cross section isolated from a testicular lump.

-

Filariasis. Microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti in a peripheral blood smear.

-

Filariasis. Appearance of microfilariae after concentration of venous blood with a Nuclepore filter.

-

Filariasis. Onchocercomas of the forearm skin (sowda) in a Sudanese man.

-

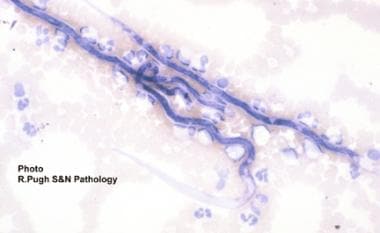

Filariasis. Adult Onchocerca volvulus contained within onchocercomas of the skin.

-

Filariasis. Microfilariae of Loa loa detected in skin snips.

-

Filariasis. Microfilariae of Mansonella perstans in peripheral blood.