Background

Anatomic structures of the stomach are divided into the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The fundus serves as the reservoir for ingested meals, while the distal stomach churns and mixes food with digestive enzymes and initiates the digestive process. Once the foods are processed, the pylorus releases the food in a controlled fashion downstream into the duodenum.

The capacity of the stomach in adults is approximately 1.5-2 liters, and its location in the abdomen allows for considerable distensibility. Gastric motility is controlled by myogenic (intrinsic), circulating hormonal, and neural activity (gastric plexus, myenteric plexus, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves). Alterations in the gastric anatomy after surgery or interference in its extrinsic innervation (vagotomy) may have profound effects on the gastric reservoir and pyloric sphincter mechanism and, in turn, alter gastric emptying. These effects, for convenience, have been termed postgastrectomy syndromes.

Postgastrectomy syndromes include small capacity, dumping syndrome, bile gastritis, afferent loop syndrome, efferent loop syndrome, anemia, and metabolic bone disease. Postgastrectomy syndromes are iatrogenic conditions that may arise from partial gastrectomies, independent of whether the gastric surgery was initially performed for peptic ulcer disease, cancer, or weight loss (bariatric). The surgical procedures include Billroth-I, Billroth-II, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. [1]

Hertz made the association between postprandial symptoms and gastroenterostomy in 1913. [2] Hertz stated that the condition was due to "too rapid drainage of the stomach." Wyllys et al first used the term "dumping" in 1922 after observing radiographically the presence of rapid gastric emptying in patients with vasomotor and GI symptoms. [3]

Pathophysiology

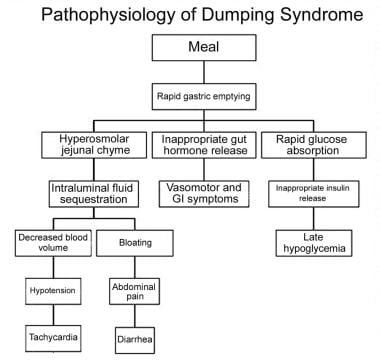

Dumping syndrome is the effect of altered gastric reservoir function, abnormal postoperative gastric motor function, and/or pyloric emptying mechanism. [4, 5] See the image below.

Clinically significant dumping syndrome occurs in approximately 10% of patients after any type of gastric surgery and in up to 50% of patients after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Dumping syndrome has characteristic alimentary and systemic manifestations. It is a frequent complication observed after a variety of gastric surgical procedures, such as vagotomy, pyloroplasty, gastrojejunostomy, and laparoscopic Nissan fundoplication. Dumping syndrome can be separated into early and late forms, depending on the occurrence of symptoms in relation to the time elapsed after a meal.

Postprandially, the function of the body of the stomach is to store food and to allow the initial chemical digestion by acid and proteases before transferring food to the gastric antrum. In the antrum, high-amplitude contractions triturate the solids, reducing the particle size to 1-2 mm. Once solids have been reduced to this desired size, they are able to pass through the pylorus. An intact pylorus prevents the passage of larger particles into the duodenum. Gastric emptying is controlled by the fundic tone, antropyloric mechanisms, and duodenal feedback. Gastric surgery alters each of these mechanisms in several ways.

Gastric resection reduces the fundic reservoir, thereby reducing the stomach's receptiveness (accommodation) to a meal. Vagotomy increases the gastric tone, similarly limiting accommodation. An operation in which the pylorus is removed, bypassed, or destroyed increases the rate of gastric emptying. Duodenal feedback inhibition of gastric emptying is lost after a bypass procedure, such as gastrojejunostomy. Accelerated gastric emptying of liquids is a characteristic feature and a critical step in the pathogenesis of dumping syndrome. Gastric mucosal function is altered by surgery, and acid and enzymatic secretions are decreased. Also, hormonal secretions that sustain the gastric phase of digestion are affected adversely. All these factors interplay in the pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.

The accommodation response and the phasic contractility of the stomach in response to distention are abolished after vagotomy or partial gastric resection. [6] This probably accounts for the immediate transfer of ingested contents into the duodenum.

Early dumping syndrome and reflux gastritis are less frequent when segmented gastrectomy rather than distal gastrectomy is performed for early gastric cancer. [7] In persons with long segment Barrett esophagus treated with a truncal vagotomy, partial gastrectomy, and Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, 41% developed dumping within the first 6 months after surgery, but severe dumping is rare (5% of cases). [8] The dumping syndrome occurs in 45% of persons who are malnourished and who have had a partial or complete gastrectomy. [9]

The late dumping syndrome is suspected in the person who has symptoms of hypoglycemia in the setting of previous gastric surgery, and this late dumping can be proven with an oral glucose tolerance test (hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia), as well as gastric emptying scintigraphy, which shows the abnormal pattern of initially delayed and then accelerated gastric emptying. [10]

Early dumping

Rapid emptying of gastric contents into the small intestine or colon may result in high amplitude propagated contractions and increased propulsive motility, thereby contributing to the diarrhea seen in persons with the dumping syndrome. [11] The emptying of liquids is fast relative to persons without distal gastrectomy with Billroth-I reconstruction. [12]

Symptoms of early dumping syndrome occur 30-60 minutes after a meal. Symptoms are believed to result from accelerated gastric emptying of hyperosmolar contents into the small bowel. This leads to fluid shifts from the intravascular compartment into the bowel lumen, resulting in rapid small bowel distention and an increase in the frequency of bowel contractions. Rapid instillation of liquid meals into the small bowel has been shown to induce dumping symptoms in healthy individuals who have not had gastric surgery. Bowel distention may be responsible for GI symptoms, such as crampy abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea. Intravascular volume contraction due to osmotic fluid shifts is perhaps responsible for the vasomotor symptoms, such as tachycardia and lightheadedness.

This hypothesis has been questioned for several reasons. First, the severity of dumping is not reliably related to the volume of hypertonic solution ingested. Second, intravenous infusion sufficient to prevent the postprandial fall in plasma volume may not abolish the dumping symptoms. Furthermore, Kalser and Cohen measured intrajejunal osmolarity and glucose content using a continuous perfusion method. [13] They found that the degree of dilution of the hyperosmolar glucose in patients who are postgastrectomy was similar in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects.

Provocation with oral glucose in patients with early dumping generally provokes an increase in the heart rate. Although vasoconstriction is expected in a volume-contracted state, patients with dumping syndrome have vasodilation. [14] An increase in blood flow to the superior mesenteric artery has been described in patients with dumping syndrome. This peripheral and splanchnic vasodilatory response seems to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of dumping.

In experimentally induced dumping in dogs, symptoms can be induced in a healthy animal by the transfusion of portal vein blood. This led to the hypothesis that humoral factors may have an important role in the pathogenesis of dumping. Some evidence suggests that hyperosmolar small intestine content leads to serotonin release which, in turn, leads to mesenteric and peripheral vasodilation. It results in fluid shifts and hypotension in the early phase of dumping syndrome.

The postprandial release of gut hormones, such as enteroglucagon, peptide YY, pancreatic polypeptide, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1), and neurotensin, is higher in patients with dumping syndrome compared with asymptomatic patients after gastric surgery. Some or all of these peptides are likely to participate in the pathogenesis of dumping syndrome. Glucagon, GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) levels were higher in those with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, as compared with those nonsurgical patients who were overweight or morbidly obese. [15] The exaggerated postprandial GLP-1 release contributes to the symptoms of early dumping by activating sympathetic outflow. [16]

One of the effects of these hormones is the retardation of proximal GI motility and the inhibition of secretion. This function is called the ileal brake. Some authors have suggested that the accelerated release of these hormones is an attempt to activate the ileal brake, thereby delaying proximal transit time in response to the rapid delivery of food to the distal small bowel.

Late dumping

Late dumping occurs 1-3 hours after a meal. The pathogenesis is thought to be related to the early development of hyperinsulinemic (reactive) hypoglycemia. [17, 18] Rapid delivery of a meal to the small intestine results in an initial high concentration of carbohydrates in the proximal small bowel and rapid absorption of glucose. This is countered by a hyperinsulinemic response. The high insulin levels stay for longer period and are responsible for the subsequent hypoglycemia. Intrajejunal glucose induces a higher insulin release than does the intravenous infusion of glucose. [19] The serum glucose levels were the same in both experiments. This effect of enhanced insulin release after an enteral glucose load as compared to intravenous glucose administration is called the incretin effect.

Two hormones are thought to play a pivotal role in the incretin effect. These are glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and GLP-1. In human studies, an increase in GLP-1 response has been noted after an oral glucose challenge. An increased GLP-1 response has been noted in patients after total gastrectomy, esophageal resection, and partial gastrectomy. Furthermore, a positive correlation was found between the rise in plasma GLP-1 and insulin release.

An exaggerated GLP-1 response likely plays an important role in the hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia in patients with late dumping. The reason why some patients remain asymptomatic after gastric surgery whereas others develop severe symptoms remains elusive.

Etiology

Dumping can be separated into early and late forms depending on the occurrence of symptoms in relation to the time elapsed after a meal. Both forms occur because of the rapid delivery of large amounts of osmotically active solids and liquids to the duodenum. This is a direct result of alterations in the storage function of the stomach and/or pyloric emptying mechanism.

The severity of dumping syndrome is proportional to the rate of gastric emptying. Postprandially, the stomach assumes its reservoir function to allow initial chemical digestion by acid and proteases before transferring food to the antrum. In the antrum, high-amplitude contractions triturate solids. Once solids have been reduced to 1-2 mm, they are able to empty through the pylorus. An intact pylorus has a separating function that prevents the passage of larger particles into the duodenum. Gastric emptying is controlled by fundic tone, antropyloric mechanisms, and duodenal feedback. Gastric surgery alters these mechanisms in several ways.

Gastric resection can reduce the fundic reservoir, thereby reducing the receptiveness of the stomach to a meal. Similarly, vagotomy increases gastric tone, limiting accommodation.

Any operation in which the pylorus is removed, bypassed, or destroyed increases the rate of gastric emptying. Duodenal feedback inhibition of gastric emptying is also lost after bypass of the duodenum with gastrojejunostomy. Accelerated early gastric emptying of liquids is a characteristic feature and a critical step in the pathogenesis of dumping syndrome.

Gastric mucosal function is altered by surgery, and acid and enzymatic secretions are decreased. Also, hormonal secretions that sustain the gastric phase of digestion are adversely affected.

Epidemiology

The global incidence and severity of symptoms in dumping syndrome are related directly to the extent of gastric surgery. [5, 20] [21]

United States data

An estimated 20-50% of all patients who have undergone gastric surgery have some symptoms of dumping. [21] However, only 1-5% are reported to have severe disabling symptoms. [21] The incidence of significant dumping has been reported to be 6-14% in patients after truncal vagotomy and drainage and from 14-20% after partial gastrectomy. The incidence of dumping syndrome after proximal gastric vagotomy without any drainage procedure is less than 2%. Newer gastric operations, such as proximal gastric vagotomy (which produces minimal disturbance of gastric emptying mechanisms), are associated with a much lower incidence of postgastrectomy syndromes. In the pediatric population, dumping syndrome is described almost exclusively in children who have undergone Nissen fundoplication. [22]

Reductions in the need for elective gastric surgery have led to a decline in the frequency of postgastrectomy syndromes. A 10-fold reduction has occurred in elective operations for peptic ulcer disease in the last 20-30 years. Although this trend preceded the advent of histamine-2 receptor antagonists, these drugs and proton pump inhibitors have accelerated the decline. Helicobacter pylori treatment and eradication in patients with peptic ulcer disease have further decreased the need for surgery.

Although the need for elective surgery for peptic ulcer disease has declined, the need for emergency surgery has remained the same over the last 20 years. Emergency surgery tends to be more mutilating to the stomach. This increases the incidence of more severe symptoms.

Gastric surgery is also performed as part of the care of persons with a gastric malignancy, or as an approach to weight loss (bariatric surgery). Bariatric surgery is the only satisfactory long-term treatment for severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] 40 kg/m² or greater, or 35 kg/m² or greater with severe obesity-associated comorbidities, such as diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, or debilitating degenerative arthritis). Even in specialized units, the mortality rate of bariatric surgery may be 1%, and serious complications may occur in about 10% of cases. [23]

Some 80% of the deaths that occur within a month of bariatric surgery arise from anastomotic leaks, pulmonary emboli, and respiratory failure. Other authors report that long-acting octreotide is as effective in the long term as subcutaneous octreotide, with superior symptom control as assessed by the Gastrointestinal Specific Quality of Life Index, better maintenance of body weight, and higher quality of life. [24] Pancreatic nesidioblastosis or pancreatic islet cell hyperplasia has been speculated to contribute to the sometimes disabling neurologic immune restoration inflammatory syndrome (NIRIS). Resection of this hyperplasia -- and therefore removing the exaggerated insulin response -- has been proposed.

Sex-related demographics

A female preponderance exists in the incidence of postgastrectomy syndromes.

-

Pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.