Practice Essentials

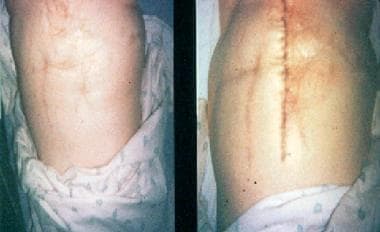

Factitious disorder imposed on self refers to the psychiatric condition in which patients deliberately produce or falsify symptoms and/or signs of illness in themselves for the principle purpose of achieving emotional gratification. The symptoms or signs can be psychological or physical. (See the image below)

Classic multiple scarred abdomen of woman with Munchausen syndrome. Photograph on left shows abdomen as it appeared on presentation, after patient had undergone 42 largely unwarranted operations. Photograph on right shows abdomen after additional surgery revealed authentic colon cancer. Courtesy of Marc D Feldman, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine.

Classic multiple scarred abdomen of woman with Munchausen syndrome. Photograph on left shows abdomen as it appeared on presentation, after patient had undergone 42 largely unwarranted operations. Photograph on right shows abdomen after additional surgery revealed authentic colon cancer. Courtesy of Marc D Feldman, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine.

Signs and symptoms

Individuals with factitious disorder imposed on self (including the historical term Munchausen syndrome) may feign illness by any of the following means:

-

A false or exaggerated (i.e., factitious) history alone

-

A factitious history plus the manipulation of assessment samples (e.g., blood or urine), instruments (e.g., thermometer) or reports (e.g., laboratory findings)

-

A factitious history plus the use of external agents that mimic disease (e.g., application of caustic agents or ingestion of unwarranted medications)

-

A factitious history plus the induction of an actual medical condition (e.g., injection of fecal bacteria)

The presence of the following factors raises the possibility that the illness is factitious:

-

Dramatic or atypical presentation

-

Inconsistencies between history and objective findings

-

Details that are vague and inconsistent, though possibly plausible on the surface

-

Long medical record with multiple admissions at various hospitals in different cities

-

Knowledge of textbook descriptions of illness; a presentation that hews too closely to the textbook example

-

Admission circumstances that do not conform to an identifiable medical or mental disorder

-

Employment or education in a medically related field

-

Pseudologia fantastica (gratuitous, often self-aggrandizing lies)

-

Presentation during times when old medical records are difficult to access or when experienced staff are less likely to be present, or refusal to allow access to outside records

The physical examination frequently suggests an extensive history of illnesses and injuries. Findings that may raise suspicions include the following:

-

Multiple surgical scars (if on the abdomen, they often create a so-called gridiron abdomen)

-

Evidence of self-induced physical signs

-

Inconsistent or implausible findings on examination

-

Absence of physical signs consistent with the history (e.g., lack of dehydration in patients complaining of persistent diarrhea and vomiting)

-

Cardiac presentations (cardiac Munchausen syndrome, or cardiopathia fantastica)

-

Manifestations that appear worse when the patient is undergoing active examination than when he or she is unaware of being observed

On mental status examination, possible findings include the following:

-

Attitude ranging from overeager for assessment and even invasive treatment to evasive and vague regarding details

-

Mood and affect that are brighter than would be expected on the basis of the patient’s ostensible medical condition

-

In factitious disorder with predominantly psychological signs and symptoms, perceptual abnormalities, suicidality or homicidality, or aberrant cognitive functioning such as suspect problems in orientation and recall

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Fundamental diagnostic principles in the setting of suspected factitious disorder are as follows:

-

Follow the basic procedures for responding to the patient’s apparent signs and symptoms

-

Know the reliability and validity of the medical tests performed

-

Respect base-rate information about the prevalence of various diseases that must be excluded

Laboratory studies can be especially helpful in facilitating the diagnosis of many physical illnesses as factitious. Examples include the following:

-

Determining the serum insulin−to−C-peptide ratio during a hypoglycemic episode to assess for exogenous insulin injection

-

Filtration of urine and chemical analysis to assess for authentic versus spurious kidney stones

-

Tissue biopsy to help detect foreign material injected to simulate naturally occurring disease

A common finding is test results that are inconsistent with the claimed illness. A particular difficulty in this setting is that many of these patients have a medical background and thus are likely to be familiar with the routine tests performed for a particular presentation.

Other studies that may be considered include the following:

-

Diagnostic imaging, particularly when the patient presents with a well-established medical problem of a type that can be easily imaged

-

Electromyography

-

Nerve conduction velocity tests

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Initial care and stabilization are driven by the presenting symptoms. Even when there are good reasons for suspecting factitious disorder, ordinary care must be provided until the patient is fully diagnosed. However, physicians should remain alert to the possibility of deception. Patients should receive surgical care as needed to treat any comorbid conditions and complications.

If the diagnosis of factitious disorder is clear or strongly suspected, psychiatric consultation and referral should be offered even if admission for the medical problems is declined. In the inpatient setting, the psychiatric consultant can assist in clarifying the diagnosis, provide education to the medical team regarding the illness, and discuss options for confronting the patient.

Confrontation should be done in a supportive manner, informing the patient of the team's suspicions and the evidence upon which it is based. The medical team should maintain an attitude that is understanding and supportive during the confrontation and throughout treatment. Team members may express empathy for the distress the patient must have been in, or the stress he or she was under that resulted in illness-producing behaviors. Comments that express a concern for the ongoing health and wellbeing of the patient and a desire to continue taking care of the patient will be helpful in maintaining the relationship.

Psychiatric treatment should be offered to the patient and the importance of follow-up care for the patient's mental health and wellbeing should be emphasized. Some patients will resist the involvement of psychiatry, but concerns about the possibility of recurrence of the condition without adequate follow-up should be voiced. The presence of a skilled and empathic consulting psychiatrist who is introduced as an intrinsic part of the medical team may also help encourage participation.

In the treatment of factitious disorder, supportive psychotherapy can be beneficial. However, little information is available on which type is most helpful. Options include the following:

-

Family therapy

-

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

-

Supportive psychotherapy

There is little evidence to support the efficacy of any particular pharmacologic intervention in treating factitious disorder; however, the following principles should apply:

-

Pharmacologic therapy may be indicated for concurrent psychiatric diagnoses

-

Drugs may also be considered for treatment of the presenting symptoms

-

Caregivers should routinely copy each other on every progress note and prescription, with ongoing care contingent on the patient’s signing consent forms; if abusable medications are used, written contracts must be signed by doctor, patient, and witness

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Factitious disorder imposed on self (including what is often referred to as Munchausen syndrome) is 1 of the 2 forms of factitious disorder (the other being factitious disorder imposed on another). [1, 2] In this psychiatric condition, a patient deliberately produces or falsifies symptoms and/or signs of illness for the principal purpose of emotional gratification from appearing to be sick. In so doing, the patient disobeys the following unwritten rules of being a patient:

-

The patient attempts to provide an honest history

-

The patient’s symptoms result from accident, injury, or chance

-

The patient seeks treatment with the goal of recovering and so will cooperate with treatment toward that end

Patients with factitious disorder waste precious time and resources through unnecessary hospital admissions, expensive investigatory tests, and, sometimes, lengthy hospital stays. Moreover, patients with factitious disorder are among the most challenging and troublesome for busy clinicians. Patients with factitious disorder can generate feelings of anger, frustration, or bewilderment, because they violate the expectations of physicians and staff that patients should “behave like patients.”

The modern history of factitious disorder began in 1951, when Richard Asher described case reports of patients who habitually migrated from hospital to hospital, seeking admission through feigned symptoms while embellishing their personal history. [3] Asher named this condition Munchausen's syndrome, after Baron von Munchhausen, a well-respected, retired German cavalry officer who had tales of his life stolen and parodied in a booklet published in England in 1785. The following were said to be typical of persons with this syndrome:

-

Exhibiting numerous surgical scars, especially in the abdomen

-

Displaying a truculent or evasive manner

-

Providing a dramatic medical history of questionable veracity

-

Attempting to conceal such documents as hospital discharge forms or insurance claims

Abdominal, hemorrhagic, and neurologic subtypes of the syndrome were distinguished in Asher's report.

Since Asher’s initial description, numerous reports of patients producing or falsifying almost every conceivable illness have appeared in the literature. The type of patient described by Asher is now thought to represent a minority of cases of factitious disorder. The term "Munchausen syndrome" is best reserved for the subset of patients who have a chronic variant of factitious disorder with predominantly physical signs and symptoms as described below. In practice, however, many still use this term interchangeably with factitious disorder, and this confusion is reflected in the case literature. The case literature on factitious disorder reflects a bias toward the more extreme cases and those that pose the greatest medical danger—that is, cases that almost always involve induction of severe illness by the patient (eg, suppression of bone marrow through surreptitious use of chemotherapy medications).

In 1977, the term "Munchausen syndrome by proxy" entered the medical lexicon as a means of describing cases in which an individual artificially produces illness in another person—typically, a mother producing illness in a young child.

Diagnostic criteria (DSM-5)

In the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), factitious disorder is divided into the following 2 types: [4]

-

Factitious disorder imposed on self

-

Factitious disorder imposed on another (formerly factitious disorder by proxy)

The specific DSM-5 criteria for factitious disorder imposed on self are as follows [4] :

-

Falsification of physical or psychological signs or symptoms, or induction of injury or disease, associated with identified deception

-

The individual presents himself or herself to others as ill, impaired, or injured

-

The deceptive behavior is evident even in the absence of obvious external rewards

-

The behavior cannot be better explained by another mental disorder, such as delusional disorder or another psychotic disorder

When an individual falsifies illness in another (eg, a child, an adult, or a pet), the diagnosis is factitious disorder imposed on another. This diagnosis is applied to the perpetrator, not the victim; the victim may be given an abuse diagnosis (eg, child physical abuse). The specific DSM-5 criteria for factitious disorder imposed on another are as follows [4] :

-

Falsification of physical or psychological signs or symptoms, or induction of injury or disease, in another, associated with identified deception

-

The individual presents another individual (ie, the victim) to others as ill, impaired, or injured

-

The deceptive behavior is evident even in the absence of obvious external rewards

-

The behavior cannot be better explained by another mental disorder, such as delusional disorder or another psychotic disorder

In both types of factitious disorder, the duration is specified as either a single episode or recurrent episodes (≥2 events of falsification of illness or induction of injury).

Although many health professionals still use the term Munchausen syndrome to describe all persons who intentionally feign or produce illness to assume the sick role, this syndrome is not included as a discrete mental disorder either in DSM-5 [4] or in the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) . In both systems, the official diagnosis for such cases is factitious disorder (300.19 in DSM-5, F68.1 in ICD-10).

Nevertheless, numerous experts have identified a distinct subset of patients with factitious disorder for whom they reserve the term Munchausen syndrome. The subtype referred to as Munchausen syndrome can be distinguished by the following characteristics:

-

The factitious illness behavior is particularly chronic and severe and may be practiced to the exclusion of most other activities; the signs and symptoms of illness or injury are intentionally produced through medically dangerous manipulations of the patient’s body (eg, self-inflicted infection or excessive warfarin ingestion), thereby virtually guaranteeing hospitalization; these patients willingly, even eagerly, submit to invasive interventions (eg, surgery)

-

Peregrination (itinerancy, or wanderlust) is observed; the patient may move from hospital to hospital, from town to town, and even from country to country to find a new audience once his or her ruse is uncovered

-

In classic cases, pseudologia fantastica is present; the patient makes false claims about distinguished accomplishments, educational credentials, relations to famous persons, and so forth

In addition to this diagnostic triad, some authors invoke further diagnostic elements. For instance, in relation to peregrination and pseudologia fantastica, the patient may use aliases or adopt false identities. Patients with Munchausen syndrome have little or no significant social contact with anyone other than health care professionals.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of factitious disorder has not been determined. No causative brain defect or dysfunction has been identified. A study of 5 cases suggested neurocognitive deficits. One case study reported that single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) found hyperperfusion of the right hemithalamus in a patient with factitious disorder. [5] It remains to be seen whether these results are replicable in larger samples and, if so, how these brain dysfunctions are linked to factitious illness behavior. Electroencephalography (EEG) has not been specific.

Some patients with factitious disorder show abnormalities on psychological testing. Such individuals often have associated personality disorders (eg, poor impulse control, self-destructive behavior, or borderline or passive-aggressive personality trait or disorder). However, it remains unclear how these constellations of personality disorders are related to the primary syndrome. Patients are adept at concealing the factitious nature of their illnesses and are markedly resistant to psychiatric evaluation. Information is often difficult to obtain.

Etiology

The etiology of factitious disorder is poorly defined. These patients are so elusive that it is very difficult to conduct systematic empiric research on them. Most of the literature consists of anecdotal or case reports. Psychoanalytic hypotheses have been put forth to explain this disorder, but the volume of this literature is quite small in comparison with the pertinent literature on the psychodynamics of other conditions in the category of somatic symptom and related disorders.

Whereas false illness experiences in similar disorders are regarded as unconsciously produced and thus amenable to traditional psychoanalytic explanations involving the notion of defense against unacceptable wishes or unspeakable fears, the false illness behavior in factitious disorder is conscious and intentional and thus less amenable to such explanations. Nevertheless, some psychoanalytic writers have argued that whereas the illness behavior of patients with factitious disorder is conscious, the reasons for the behavior are not.

Since Asher’s original description, several authors have suggested that factitious illness behavior is a primitive defense mechanism against sexual and aggressive impulses. Others have proposed that patients with factitious disorder subject themselves to painful medical procedures as a form of self-punishment. Still others have hypothesized that the cruel and embarrassing deception of physicians is an expression of oedipally based hostility toward authority figures.

More contemporary authors, noting the high degree of comorbidity with cluster B personality disorders, have suggested that the sick-role behavior seen in factitious disorder might be a means of establishing or stabilizing patients’ sense of self and their relations to others. Adoption of the sick role brings them unconditional acceptance and concern, and admission to a hospital gives them a clearly defined role in a social network. This automatic sense of importance and belonging might be difficult for them to secure in more routine social contexts.

Case studies support the role of social learning mechanisms in factitious illness behavior. Many patients with factitious disorder either personally experienced a severe illness in childhood or, as a child, had a family member who experienced a severe illness. These experiences introduce the child to the various benefits and dispensations attached to the sick role, and they may predispose a person with other psychological vulnerabilities to engage in factitious illness behavior.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing factitious disorder remain largely unclear. On the basis of histories obtained from patients with factitious disorder, the following can be projected as characteristics that may predispose an individual to develop a factitious illness:

-

Having had other mental disorders or medical conditions in childhood or adolescence that resulted in extensive medical attention

-

Holding a grudge against the medical profession or having had an important relationship with a physician in the past

-

Having a personality disorder, especially borderline, narcissistic, or antisocial personality disorder

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The prevalence of factitious disorder is unclear. Epidemiologic data on this disorder are scarce, in large part because patients manifesting factitious illness behavior generally are not open and honest about their medical deceptions.

Many authorities believe that factitious disorder is underdiagnosed because patients' willful deceptions are commonly missed by medical staff. Others, however, believe that it may actually be overdiagnosed in some cases because patients may migrate from hospital to hospital and receive a discrete diagnosis at each one. It is unclear which factitious illnesses are most common; however, it is generally agreed that overall, factitious psychological symptoms are much less common than factitious physical symptoms.

Studies of medical patients suggest that the prevalence of factitious disorder among hospital inpatients is probably in the range of 0.2–1%. [6, 7] Although patients with factitious disorder have claimed to have almost every medical condition known, the prevalence of the disorder is particularly high in a few select groups, including patients who present with persistent rashes and nonhealing wounds, unexplained anemia, neurologic problems, endocrine-related problems, hematuria, or joint and connective-tissue symptoms. [8]

As might be expected, the prevalence is even higher among patients with unexplained or intractable medical complaints. For example, of patients referred for evaluation of fever of unknown origin at the US National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease, 9.3% had factitious disorder. Of material submitted by patients as kidney stones, 2.6% was found to be nonphysiologic and probably fraudulent. In one study, an astounding 40% of brittle diabetics intentionally altered their medication compliance or diet to produce diabetic instability.

International statistics

Whether the epidemiology of factitious disorder differs in countries other than the United States is unclear. Case reports indicate that the diagnosis has been made in eastern Europe, Mediterranean countries, Asia, Africa, and South America.

Of patients referred to the consultation-liaison service of a large teaching hospital in Toronto, 0.8% (10 of 1288) had factitious disorder. Physicians surveyed in Germany regarding the 1-year prevalence of factitious disorder among their patients provided an average estimate of 1.3%. [7]

Age-related demographics

The age range for persons with factitious disorder tends to be women between 20 and 40 years of age. Persons with chronic factitious disorder (i.e., Munchausen syndrome) tend to be middle-aged men. [9] Factitious disorder imposed on self has been noted in the pediatric population; [10] this condition must be distinguished from factitious disorder imposed on another (including Munchausen by proxy), in which an adult simulates or creates symptoms in a child to receive a generally ill-defined satisfaction from the attention and/or health care the child receives.

Sex-related demographics

Persons with factitious disorder are usually female and employed in medical fields such as nursing or medical technology; working in the medical field provides knowledge of how disease might be produced artificially and provides access to equipment (eg, syringes, chemicals) with which to do so. Persons with chronic factitious disorder (ie, Munchausen syndrome), on the other hand, tend to be unmarried men who are estranged from their families and unemployed.

The typical presentation of Munchausen syndrome is characterized by a restless journey from physician to physician and from hospital to hospital, an ever-changing list of complaints and symptoms, and an alarming variety of self-intoxications and self-injuries designed to create a better portrayal of the illness that the patient asserts he or she has.

There exists, however, a subset of adult female patients who vary from the classic presentation in that they reproduce a single set of symptoms, repeatedly. Patients in this subset exhibit less evidence of comorbid personality dysfunction than the average patient with Munchausen syndrome, and they have a strong tendency to form personal bonds with a single physician or group of physicians.

Race-related demographics

The case literature clearly shows that most patients with factitious disorder are white. In the absence of demographic data describing the racial or ethnic composition of the patient populations in which these cases were identified, it is currently impossible to know whether race represents a significant risk factor.

The more chronic and severe Munchausen variant of factitious disorder appears to follow an unremitting course, and the prognosis is generally poor. Patients frequently are unwilling to undergo mental health treatment, and even if they are willing, no well-established effective therapeutic strategy exists. Treatment may transiently ameliorate symptoms but does not appear to last in most cases, though a few individuals have recovered.

Patients with simple factitious disorder follow a more variable course, and the overall prognosis may be regarded as fair. Case reports in the literature suggest that some patients who seek treatment for factitious disorder may be able to overcome their illness. It appears that even without treatment, simple factitious disorder sometimes remits in the fourth decade of life.

The presence of a treatable concurrent mental disorder, such as major depression, is a positive prognostic sign. Some investigators believe that both disorders attenuate with age and maturity, as is the case with personality disorders.

Factitious disorder can result in morbidity and mortality either from the patient's re-creation of actual medical conditions (eg, exogenous administration of insulin) or from the measures the physician undertakes to diagnose or treat the condition (eg, unnecessary cardiac catheterizations or surgical procedures). The factitious production of illness also can lead to emotional distress and suffering for the patient and those close to the patient. No studies have quantified the total estimated morbidity and mortality from factitious disorder.

Prognosis

The more chronic and severe Munchausen variant of factitious disorder appears to follow an unremitting course, and the prognosis is generally poor. Patients frequently are unwilling to undergo therapy, and even if they are willing, no well-established effective therapeutic strategy exists. Treatment may transiently ameliorate symptoms but does not appear to last in most cases, though a few individuals have recovered.

Patients with simple factitious disorder follow a more variable course, and the overall prognosis may be regarded as fair. Case reports in the literature suggest that some patients who seek treatment for factitious disorder may be able to overcome their illness. It appears that even without treatment, simple factitious disorder sometimes remits in the fourth decade of life.

The presence of a treatable concurrent mental disorder, such as major depression, is a positive prognostic sign. Some investigators believe that both disorders attenuate with age and maturity, as is the case with personality disorders.

Factitious disorder can result in morbidity and mortality either from the patient's re-creation of actual medical conditions (eg, exogenous administration of insulin) or from the measures the physician undertakes to diagnose or treat the condition (eg, unnecessary cardiac catheterizations or surgical procedures). The factitious production of illness also can lead to emotional distress and suffering for the patient and those close to the patient. No studies have quantified the total estimated morbidity and mortality from factitious disorder.

Features that increase morbidity and mortality

Four features of factitious disorder that are particularly prominent in the more chronic and severe form of the disorder (Munchausen syndrome) significantly increase morbidity and mortality risk in this setting.

The first feature is that patients perform dangerous manipulations on their own bodies (eg, ingestion of chemical toxins, self-infection, or aggravation of wounds). Although patients with Munchausen syndrome are generally medically knowledgeable and sophisticated, their manipulations sometimes result in unintended serious injury, permanent disability, or death.

The second feature is that patients incur a substantial risk of iatrogenic illness and injury by repeatedly engaging in deceptions that cause medical care providers to perform risky diagnostic and treatment procedures. In some cases, the resultant damage is part of the patient's plan. For example, a patient who pretends to have a malignancy may desire the adverse effects of chemotherapy, or a patient may simulate adrenal gland dysfunctions with the intention of having an adrenal grand removed.

In other cases, the iatrogenic damage results from unintended medical accidents, such as adverse medication effects, allergic reactions, or surgical complications. Because patients with Munchausen syndrome subject themselves to so many medical procedures, their lifetime risk of experiencing an unintended adverse medical event is many times greater than that of the average person.

The third feature is that patients with Munchausen syndrome frequently provide incomplete or false medical history information that, by intention or through an oversight, causes increased morbidity or mortality. For example, they may experience dangerous adverse medication effects because they withhold information about known drug allergies, or they may suffer surgical complications because they fail to inform the medical staff that they have taken anticoagulant medications.

The fourth feature is that because of their factitious illness behavior, these patients may not receive serious attention from medical staff when they truly need it. Although they are more likely to claim illness or injury than typical patients are, this does not mean that they are any less likely to sustain an actual illness or injury. In some cases, even when a patient with a known history of factitious complaints is genuinely ill, medical staff may delay or withhold necessary measures so as to minimize iatrogenic risks and avoid reinforcing inappropriate behavior.

Patient Education

A patient confronted with suspicions that his or her illness is factitious may not be receptive to attempts at patient education. Nevertheless, education should be attempted in the same gentle and supportive manner with which the patient is confronted. If the patient gives permission, educating family members about the patient's condition may also be helpful. Education as to risks of noncompliance with treatment recommendations is also important, ethically and legally, because the patient may wish to sign out of the hospital against medical advice.

Efforts to educate the patient should include the following steps:

-

Convey empathy for the patient's distress that has led to the feigning or intentional production of illness

-

Inform the patient that his or her distress may improve with treatment

-

Point out to the patient that without treatment, the condition is unlikely to improve, and he or she may again seek hospitalization

-

Emphasize to the patient that each episode of producing or feigning illness can result in significant morbidity or even mortality resulting either from the production of illness or from the performance of unnecessary tests or treatments

If the patient is receptive to psychiatric treatment, patient education may be an important component of psychotherapy. Information from this article or other sources can be used to help the patient understand more about his or her illness, including the presumed origins of the factitious illness behavior and the importance of regular follow-up care with the psychiatrist.

Educational efforts targeted toward the general public are not likely to decrease the incidence of factitious disorder. It has been asserted that such efforts might help friends, family members, teachers, or coworkers to identify persons with this disorder and urge them to seek mental health care, but this assertion is debatable. It is equally possible that such efforts could lead to cruel and unwarranted skepticism toward people who have genuine chronic illnesses.

For patient and family education resources, see the Mental Health Center, as well as Munchausen Syndrome. The following Web sites may also be useful:

-

Cleveland Health Clinic, An Overview of Factitious Disorders

Ethical and Legal Issues

Patients with factitious disorder can and do litigate. A potential trigger of litigation that must be avoided is rushing to a diagnosis of factitious disorder and, as a result, missing the presence of an authentic organic disease. Symptoms should not be attributed to factitious disorder without proper investigation, and an adequate effort must be made to distinguish this disorder from malingering and conversion disorders. In particular, a patient must not be misdiagnosed as having factitious disorder merely on the basis of unpleasant personality traits.

In the past few years, a variant of factitious disorder called Munchausen by Internet has been reported in which individuals with this condition use Internet bulletin boards and online patient self-help groups to further gratify their primary need to "be sick." Challenges to the deceptions, whether online or in person, can lead to extensive civil legal proceedings. Physicians may become involved as expert witnesses or as witnesses-of-fact to one of the Munchausen patient's multiple presentations to a hospital.

Expert witnesses in legal proceedings involving patients with factitious disorder (including workers' compensation or tort claims) must obtain and review extensive information from collateral sources in performing a thorough evaluation of the patient. Medical and psychiatric records antedating the injury should be consulted. While one may argue that the pursuing of secondary financial gain through initiating a lawsuit against a treatment provider moves a patient with factitious disorder into the realm of malingering, the patient may also derive important psychological benefits from winning a lawsuit. Family members may criticize the patient with extensive somatic complaints and claims of disability. Initiating and winning litigation may deflect blame for his or her condition onto the treatment provider and validate the patient's explanation for difficulties in his or her life. [11] Expert witnesses should be prepared to make the distinction between primary and secondary gain clear to juries and assist juries in distinguishing among malingering, somatic symptom disorder, and factitious disorder.

Many of the legal and ethical issues arising in cases of medical deception have been debated extensively and have resulted in courtroom judgments. The controversy has yet to resolve most of these issues, which are discussed below, such that no clear guidance is available to direct the treating physician's response.

Status as patient

"Patienthood," as conceptualized by most commentators and organizations, such as the American Medical Association (AMA), includes in part the notion that the individual seeks medical care in order to get well and overcome an illness or injury. One may ask whether an individual with facititious disorder, whose goal is different (ie, to assume the sick role through factitious illness in order to receive care), should appropriately be considered to be a patient. If what it means to be a patient is strictly conceptualized in this way, then the professional obligations owed to patients would not extend to those with factitious disorders. They may not be considered to be entitled to admission, treatment, appropriate notice before termination, and the like.

Responsibility of physician

The physician who has discovered that a person has been feigning illness may be thwarted from sharing that information with others. The patient may explicitly refuse to give permission to share this vital information with other healthcare professionals or even with the patient's own family members. One proposed solution in such cases is for the physician simply to state, "The patient has forbidden me to comment on whether he or she has a factitious disorder," thereby tacitly encouraging others to read between the lines.

Another possible solution echoes the question of whether the duty of confidentiality is owed to someone who may not qualify as a patient. Several commentators have argued that the doctor-patient relationship, through which the right to confidentiality is established, requires that both the doctor and the patient carry out their roles in good faith. According to this view, the doctor-patient relationship ceases to exist when the patient engages in medical deception (ie, acts in bad faith). Without the restrictions imposed by the duty of confidentiality, the physician would be free to share information about the individual.

Legal culpability of patient

Patients who engage in the deliberate production of factitious illnesses steal the time of doctors and other caregivers, and waste medical resources and supplies. An individual who is caught stealing even inexpensive merchandise from a department store will invariably be confronted and often be criminally charged. Yet a patient with factitious disorder will rarely be subjected to criminal indictment, despite the enormous costs. Nevertheless, one such case was heard in Arizona and resulted in a court finding of fraud and an order of reimbursement against the patient. Other such cases are likely.

Mismanagement of real ailment

The standard medical malpractice claim made by patients with factitious disorder against care providers is that the patient's ailment was not factitious, but was real, and was mismanaged such that the patient is now permanently disabled or disfigured. These cases are notoriously difficult to defend, in terms of both time and money, even when the patient has been observed to induce self-harm. Regardless of the evidence, judges and juries tend to find factitious disorder scarcely believable and to assume that a patient who has this condition would be obviously psychotic. The presence of a well-behaved, neatly groomed patient in the courtroom can clash with that erroneous assumption, leading to surprisingly large settlements or verdicts in favor of patients.

Mismanagement of feigned ailment

Another possible malpractice claim is the obverse of the one above. In this scenario, a patient with factitious disorder eventually sues caregivers for their failure to detect that his or her illness was feigned. The patient argues that as a consequence of this failure, any and all treatments were misapplied, the iatrogenic effects were completely unwarranted, and the physician breached the standard of care in diagnosis. In one case of this sort, a settlement in excess of $300,000 was awarded to the patient.

Patient privacy

When facititious disorder is suspected, caregivers may wish to search a patient's belongings for items used in perpetrating the factitious illness. However, doing so without first obtaining consent likely violates the patient's right to privacy. Consent can sometimes be gained, however, by revealing one's suspicions that the illness is factitious and then asking for permission to search. Patients may insist they have nothing to hide and allow the search. In addition, many hospitals require patients to consent to room searches as a condition of admission.

Covert surveillance (eg, with cameras hidden in ceiling panels) intended to catch factitious illness behavior is somewhat more controversial. The use of video cameras to monitor patient behavior probably does not violate privacy considerations if the cameras were already in routine use to monitor patients' rooms (as in some critical care wards). However, covert operation of cameras for the specific purpose of catching a patient with factitious disorder may be problematic.

The arguments for and against these measures hinge on whether there is a reasonable expectation of privacy in a hospital room. Many legal precedents support the notion that such an expectation is unreasonable, but these derive from cases of abuse related to factitious disorder imposed on another (Munchausen syndrome by proxy), in which the suspected abuse could not be confirmed or ruled out without resorting to such interventions (eg, the patient was a nonverbal infant who could not provide any information).

Hospital risk management and legal advisors should meet with team members to formulate a decision as a group before covert video surveillance is initiated. Hospitals are advised to develop relevant standards and policies even if no suspicious case has ever arisen. The authors are not aware of any cases in which search warrants for hospital rooms have been issued solely on the basis of the possibility of self-damaging behavior.

Confidentiality of patient information

Estabilishing registries of patients with factitious disorder that are shared among treatment centers or are made available nationally or internationally has been proposed. These registries would be used to determine whether a patient who is suspected of medical deception has been previously identified as having factitious disorder.

Although the existence of such registries would undoubtedly hinder the ability of such patients to carry out their deceptions at successive hospitals, they appear to be legally problematic in the United States. Such registries of this type appear to violate the patient's confidentiality, particularly since the establishment of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules. Interestingly, registries of troublesome patients are maintained in some other countries.

Patients' rights advocates caution that people who are placed on these lists may receive inadequate care for medical complaints because of a presumption that their complaints must be inauthentic, which may or may not be true. They also express concern that some people may be listed simply because they were uncooperative or because the source of their complaints could not be diagnosed. Supporters of these lists, however, view themselves as helping patients by preventing unwarranted treatment of people whose judgment is impaired.

-

Classic multiple scarred abdomen of woman with Munchausen syndrome. Photograph on left shows abdomen as it appeared on presentation, after patient had undergone 42 largely unwarranted operations. Photograph on right shows abdomen after additional surgery revealed authentic colon cancer. Courtesy of Marc D Feldman, MD, University of Alabama School of Medicine.