Practice Essentials

Choledochal cysts are congenital bile duct anomalies (see the image below). These cystic dilatations of the biliary tree can involve the extrahepatic biliary radicles, the intrahepatic biliary radicles, or both.

Signs and symptoms

Infants with choledochal cysts can present dramatically with the following:

-

Jaundice and acholic stools: In early infancy, may prompt workup for biliary atresia

-

Palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, with hepatomegaly

The clinical manifestations in older children and adults are variable. Children diagnosed with choledochal cysts after infancy typically present with intermittent biliary obstruction or recurrent bouts of pancreatitis with the following features:

-

Biliary obstructive pattern: Palpable right upper quadrant mass and jaundice

-

Primary manifestation of pancreatitis: May pose diagnostic difficulty; patients frequently have only intermittent attacks of colicky abdominal pain (elevated amylase and lipase concentrations lead to the proper diagnostic workup)

The classic triad in adults with choledochal cysts is abdominal pain, jaundice, and palpable right upper quadrant abdominal mass. However, this triad is found in only 10-20% of patients.

Adults may present with the following:

-

Abdominal pain: Most common symptom; there may be vague epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

-

Jaundice or cholangitis

-

One or more severe complications (eg, hepatic abscesses, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, recurrent pancreatitis, cholelithiasis)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Testing

No laboratory studies are specific for the diagnosis of a choledochal cyst, but some may be used to narrow the differential diagnosis. The following tests may be helpful:

-

Complete blood count with differential: Elevated white blood cell count with increased numbers of neutrophils and immature neutrophil forms may be noted in the presence of cholangitis

-

Liver function studies: Elevated hepatocellular enzymes and alkaline phosphatase levels are nonspecific for choledochal cysts

-

Serum amylase and lipase levels: Both may be elevated in the presence of pancreatitis, but they can also be elevated in the presence of biliary obstruction and cholangitis

-

Serum chemistry levels: Results may be abnormal if the patient is vomiting (hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis)

Imaging studies

The following imaging studies may be used to assess patients with suspected choledochal cysts:

-

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Help to delineate the anatomy of the lesion and the surrounding structures; can also assist in defining the presence and extent of intrahepatic ductal involvement

Procedures

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are used to supplement the above noninvasive imaging studies when those studies fail to sufficiently delineate the relevant anatomy.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Surgery

The treatment of choice for choledochal cysts is complete excision with construction of a biliary-enteric anastomosis to restore continuity with the gastrointestinal tract. [5, 6]

The surgical management for each choledochal cyst type is described as follows:

-

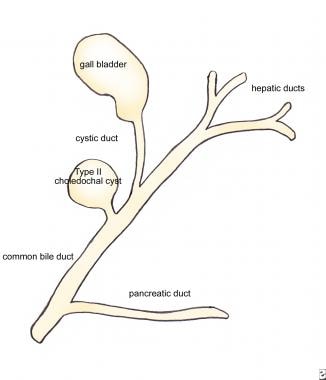

Type II: Complete excision of the dilated diverticulum comprising a type II choledochal cyst; the resultant defect in the common bile duct is closed over a T-tube

-

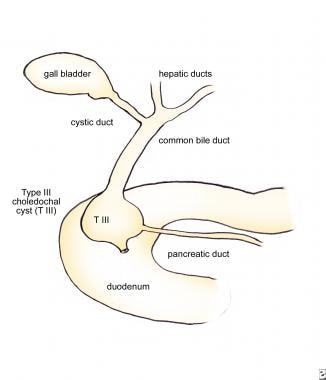

Type III (choledochocele): Therapeutic choice depends on the size of the cyst; choledochoceles measuring 3 cm or less can be treated effectively with endoscopic sphincterotomy, whereas lesions larger than 3 cm (which typically produce some degree of duodenal obstruction) are excised surgically via a transduodenal approach—if the pancreatic duct enters the choledochocele, reimplantation into the duodenum may be required following excision of the cyst

-

Type IV: Complete excision of the dilated extrahepatic duct, followed by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to restore continuity; intrahepatic ductal disease does not require dedicated therapy unless hepatolithiasis, intrahepatic ductal strictures, and hepatic abscesses are present (in such instances, resection of the affected hepatic segment or lobe is performed)

-

Type V (Caroli disease): Hepatic lobectomy for disease limited to one hepatic lobe (left lobe usually affected); however, one should carefully examine the hepatic functional reserve before committing to such therapy; patients with bilobar disease manifesting signs of liver failure, biliary cirrhosis, or portal hypertension may require liver transplantation

-

Lilly technique: When the cyst adheres densely to the portal vein secondary to long-standing inflammatory reaction, it may not be possible to perform a complete, full-thickness excision of the cyst; the Lilly technique allows the serosal surface of the duct to be left adhering to the portal vein, while the mucosa of the cyst wall is obliterated by curettage or cautery—theoretically, this removes the risk of malignant transformation in that segment of the duct

Supportive measures

No medical therapy specifically targets the etiology of choledochal cysts, nor is any drug or any type of nonsurgical modality curative. Patients with choledochal cysts who present at a late stage (ie, after the development of advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension) may not be good candidates for surgery because of the prohibitive morbidity and mortality associated with these comorbid conditions.

Patients who present with cholangitis should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy directed against common biliary pathogens, such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species, in addition to other supportive measures, such as volume resuscitation.

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Choledochal cysts are congenital bile duct anomalies. These cystic dilatations of the biliary tree can involve the extrahepatic biliary radicles, the intrahepatic biliary radicles, or both. They may occur as a single cyst or in multiples within the biliary tree. In 1723, Vater and Ezler published the anatomic description of a choledochal cyst. Douglas wrote the clinical report involving a 17-year-old girl presenting with jaundice, fever, intermittent abdominal pain, and an abdominal mass. [9] The patient died a month after an attempt was made at percutaneous drainage of the mass. (See image below.)

In 1959, Alonzo-Lej produced a systematic analysis of choledochal cysts, reporting on 96 cases. He devised a classification system, dividing choledochal cysts into 3 categories, and outlined therapeutic strategies. Todani has since refined this classification system to include 5 categories. [10] This article reviews the incidence, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of choledochal cysts.

Based on findings from a retrospective analysis of 32 children and 47 adults with choledochal cysts, Shah et al concluded that because of differences with regard to the presentation, management, and histopathology of, as well as the outcomes related to, these lesions, choledochal cysts in children should be considered separate entities from those in adults. [11] The authors reported the following findings [11] :

-

A history of biliary surgery, pancreatitis, cholangitis, early postoperative complications, and late postoperative complications occurred, respectively, 5.1, 5.4, 6.4, 2.0, and 3.3 times more frequently in adults than they did in children.

-

The classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and a palpable right upper quadrant abdominal mass occurred 6.7 times more frequently in children than in adults.

-

Fibrosis of the cyst wall was peculiar to children.

-

Signs of inflammation and hyperplasia were primarily seen in adults.

-

Long-term complications occurred in 29.7% of adults but in only 9.3% of children.

For patient education resources, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Gallstones, Pancreatitis, Cirrhosis, and Abdominal Pain in Adults.

Pathophysiology

No strong unifying etiologic theory exists for choledochal cysts. The pathogenesis is probably multifactorial. [12] In many patients with choledochal cysts, an anomalous junction between the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct can be demonstrated. This occurs when the pancreatic duct empties into the common bile duct more than 1 cm proximal to the ampulla.

Some series, such as the one published by Miyano and Yamataka in 1997, have documented such anomalous junctions in 90-100% of patients with choledochal cysts. [13] This abnormal union allows pancreatic secretions to reflux into the common bile duct, where the pancreatic proenzymes become activated, damaging and weakening the bile duct wall. Defects in epithelialization and recanalization of the developing bile ducts and congenital weakness of the ductal wall also have been implicated. The result is the formation of a choledochal cyst.

These anomalies are classified according to the system published by Todani and coworkers. Five major classes of choledochal cysts exist (ie, types I-V), with subclassifications for types I and IV (ie, types IA, IB, IC; types IVA, IVB). [10, 14]

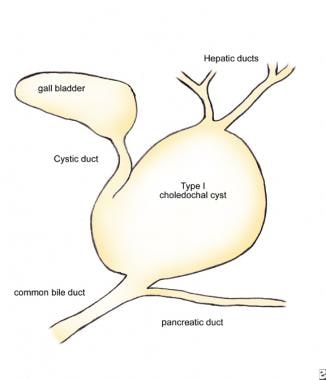

Type I cysts

Type I cysts (see image below) are the most common and represent 80-90% of choledochal cysts. They consist of saccular or fusiform dilatations of the common bile duct, which involve either a segment of the duct or the entire duct. They do not involve the intrahepatic bile ducts.

Type IA is saccular in configuration and involves either the entire extrahepatic bile duct or the majority of it.

Type IB is saccular and involves a limited segment of the bile duct.

Type IC is more fusiform in configuration and involves most or all of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Type II cysts

Type II choledochal cysts (see image below) appear as an isolated true diverticulum protruding from the wall of the common bile duct. The cyst may be joined to the common bile duct by a narrow stalk.

Type III cysts

Type III choledochal cysts (see image below) arise from the intraduodenal portion of the common bile duct and are described alternately by the term choledochocele.

Type IVA cysts

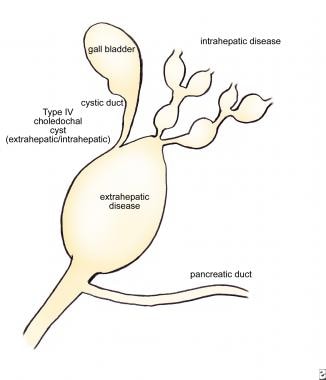

Type IVA cysts (see image below) consist of multiple dilatations of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Type IVB choledochal cysts are multiple dilatations involving only the extrahepatic bile ducts.

Type V cysts

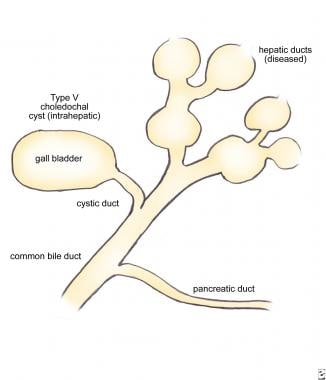

Type V (Caroli disease) cysts (see image below) consist of multiple dilatations limited to the intrahepatic bile ducts. [13]

Choledochal cyst of the proximal cystic duct

Rarely, a patient may present with an isolated choledochal cyst involving the proximal cystic duct. [15] At present, this type of cyst may be categorized as either a type II or type VI cyst. [15]

Extrahepatic bile duct duplication

Extrahepatic bile duct duplication is an extremely rare congenital anomaly. [16, 17, 18, 19] In 2020, Naumah et al reported a case of a patient diagnosed with type IC choledochal cyst using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). [19] A double common bile duct was discovered during the cholecystectomy and hepaticoenterostomy procedure; it was not observed on preoperative imaging. Difficulty in identifying this anomaly on imaging can be associated with intraoperative iatrogenic injury. The authors propose updating existing classification systems to include newly discovered variants.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Choledochal cysts are relatively rare in Western countries. Reported frequency rates range from 1 case per 100,000-150,000 to 1 case per 2 million live births.

International statistics

Choledochal cysts are much more prevalent in Asia than in Western countries. Approximately 33-50% of reported cases come from Japan, where the frequency in some series approaches 1 case per 1000 population (as described by Miyano and Yamataka). [13]

Sex- and age-related demographics

Choledochal cysts are more prevalent in females than males, with a female-to-male ratio in the range of 3:1 to 4:1.

Most patients with choledochal cysts are diagnosed during infancy or childhood, although the condition may be discovered at any age. Approximately 67% of patients present with signs or symptoms referable to the cyst before the age of 10 years. [11]

Prognosis

The prognosis after excision of a choledochal cyst is usually excellent, but it is influenced by several factors, including patient's age, cyst type, histologic features, and site. [20] Moreover, patients need lifelong follow-up because of the increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma, even after complete excision of the cyst. [21] In adults, there appears to be a 6-30% risk of malignancy associated with choledochal cyst. [20]

Morbidity/mortality

The morbidities associated with choledochal cysts depend on the age of the patient at the time of presentation. Infants and children may develop pancreatitis, cholangitis, and histologic evidence of hepatocellular damage. Adults in whom subclinical ductal inflammation and biliary stasis may have been present for years may present with one or more severe complications, such as hepatic abscesses, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, recurrent pancreatitis, cholangitis, and cholelithiasis.

Cholangiocarcinoma is the most feared complication of choledochal cysts, with a reported incidence of 9-28%. Wu and colleagues exposed cells from a cholangiocarcinoma cell line to bile from patients with choledochal cysts and from controls with structurally normal biliary systems. [22] The bile from the patients with choledochal cysts produced significantly more mitogenic activity in the cancer cell line than the bile from the controls.

Complications

Complications of choledochal cysts include the following:

-

Patients undergoing excision of a choledochal cyst are subject to the usual complications associated with surgery, including hemorrhage, wound infection, bowel obstruction, and thrombotic complications.

-

Postoperatively, patients are at risk of developing pancreatitis and ascending cholangitis.

-

Late postoperative complications include development of intrahepatic bile duct stones and cholangiocarcinoma.

-

Adult patients with long-standing subclinical ductal inflammation and biliary stasis may develop one or more of the following complications: hepatic abscesses, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, recurrent pancreatitis, and cholelithiasis.

Other potential complications include cyst rupture, secondary biliary cirrhosis, bleeding, and obstructive jaundice.

-

Operative specimen of a type I choledochal cyst.

-

Type I choledochal cyst.

-

Type II choledochal cyst.

-

Type III choledochal cyst (choledochocele).

-

Type IV choledochal cyst (extrahepatic and intrahepatic disease).

-

Type V choledochal cyst (intrahepatic, Caroli disease).

-

Nuclear medicine scan of a choledochal cyst.

-

Nuclear medicine scan of a choledochal cyst.

-

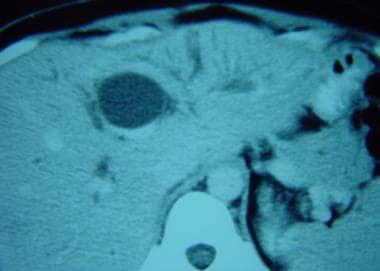

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a choledochal cyst demonstrating intrahepatic extension involving the main left hepatic duct.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a choledochal cyst involving the common hepatic duct.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a large choledochal cyst and the adjacent gall bladder.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a large, saccular type I choledochal cyst.

-

Diagnostic ultrasonogram demonstrating a type I choledochal cyst in a 4-month-old child presenting with hyperbilirubinemia and transaminase elevations.

-

Intraoperative cholangiogram of a type I choledochal cyst.

-

Intraoperative image of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to restore biliary-enteric continuity following resection of a choledochal cyst.