Practice Essentials

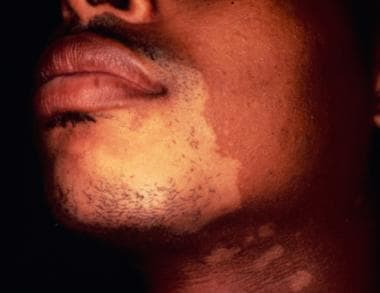

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) (see the image below) is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by localization of neoplastic T lymphocytes to the skin, with no evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis. [1] CTCL subtypes demonstrate a variety of clinical, histologic, and molecular features, and can follow an indolent or a very aggressive course. Collectively, CTCL is classified as a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Related articles include Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma and Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma.

WHO-EORTC classification of CTCLs

The 2005 World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (WHO-EORTC) classification of CTCLs is divided into those with indolent clinical behavior and those with aggressive subtypes. A third category is that of precursor hematologic neoplasms that are not T-cell lymphomas (CD4+/CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm [blastic natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoma]). [2]

In 2018, an updated version of the WHO-EORTC was published. Among the changes to CTCL classification were the addition of primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma as a new provisional entity. Also, the term “primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoma” was changed to “primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder” because of its indolent clinical behavior and uncertain malignant potential. [3]

CTCLs with indolent clinical behavior include the following [2, 3] :

-

Mycosis fungoides

-

Mycosis fungoides variants and subtypes (eg, folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, pagetoid reticulosis, granulomatous slack skin)

-

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder (eg, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis)

-

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

-

Primary cutaneous CD4 + small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (provisional)

CTCLs with aggressive clinical behavior include the following [2, 3] :

-

Sézary syndrome

-

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

-

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

-

Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (provisional)

-

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma (provisional)

-

Primary cutaneous gamma/delta-positive T-cell lymphoma

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of CTCL vary depending on the type. Mycosis fungoides is the most common type, accounting for 60% of CTCLs and almost half of all primary cutaneous lymphomas. [3]

Classic mycosis fungoides is divided into the following 3 stages:

-

Patch (atrophic or nonatrophic): Nonspecific dermatitis, patches on lower trunk and buttocks; minimal/absent pruritus

-

Plaque: Intensely pruritic plaques, lymphadenopathy

-

Tumor: Prone to ulceration

Sézary syndrome is, with mycosis fungoides, one of the classic types of CTCL, although it is relatively rare. [3] Sézary syndrome is defined by erythroderma and leukemia. Signs and symptoms include the following:

-

Edematous skin

-

Lymphadenopathy

-

Palmar and/or plantar hyperkeratosis

-

Alopecia

-

Nail dystrophy

-

Ectropion

-

Hepatosplenomegaly may be present

Ocular involvement may be evident in advanced CTCL. [4]

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

In most cases of mycosis fungoides, the diagnosis is reached owing to its clinical features, disease history, and histomorphologic and cytomorphologic findings. An additional diagnostic criterion to distinguish CTCL from inflammatory dermatoses is demonstration of a dominant T-cell clone in skin biopsy specimens by a molecular assay (ie, Southern blot, polymerase chain reaction [PCR]). Genetic testing may also be considered.

The following laboratory tests are included in the diagnostic workup of mycosis fungoides:

-

Complete blood count with differential; review the buffy coat smear for Sézary cells

-

Liver function tests: Look for liver-associated enzyme abnormalities

-

Uric acid and lactate dehydrogenase levels: These are markers of bulky and/or biologically aggressive disease

-

Flow cytometric study of the blood (include available T-cell–related antibodies): To detect a circulating malignant clone and to assess immunocompetence by quantifying the level of CD8-expressing lymphocytes

-

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-I) testing

For a diagnosis of Sézary syndrome, one or more of the following criteria should be met [5] :

-

Absolute Sézary cell count of at least 1000 cells/µL

-

Immunophenotypic abnormalities (expanded CD4+ T-cell population resulting in CD4/CD8 ratio of >10; loss of any or all of T-cell antigens CD2, CD3, CD4, and CD5; or loss of both CD4 and CD5)

-

T-cell clone in the peripheral blood shown by molecular or cytogenetic methods: Flow cytometry may be useful for differential diagnosis of precursor and peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas [6]

Imaging studies

-

Chest radiography: To determine whether there is lung involvement

-

Abdominal/pelvic computed tomography (CT) scanning: In patients with advanced mycosis fungoides (stage IIB to IVB) or those with clinically suspected visceral disease

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning: To determine visceral involvement

Staging

Although mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are types of NHL, a different staging system is used, based on the particular skin findings and findings of extracutaneous disease, as follows [7] :

-

Stage IA disease (as defined by the tumor, node, metastases blood [TNMB] system): Patchy or plaquelike skin disease involving less than 10% of skin surface area (T1 skin disease)

-

Stage IB: Patchy/plaquelike skin disease involving 10% or more of the skin surface area (T2 skin disease)

-

Stage IIB disease: Tumors are present (T3 skin lesions)

-

Stage III disease: Generalized erythroderma is present

-

Stage IVA1 disease: Erythroderma and significant blood involvement occur

-

Stage IVA2 disease: Lymph node biopsy result shows total effacement by atypical cells (LN4 node)

-

Stage IVB disease: Visceral involvement (eg, liver, lung, bone marrow) occurs

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment for early stage CTCLs includes topical therapies with or without interferon alpha (IFN-α) or oral agents, whereas advanced-stage patients are treated with chemotherapy and novel agents. Multiagent cytotoxic regimens may be palliative but seem to lack a demonstrated survival benefit. [8]

Mycoses fungoides

Symptomatic treatments, emollients, or antipruritics, plus specific topical and systemic treatment, are used to manage mycosis fungoides. Generally, topical therapies are indicated for stage I patients, and systemic therapies or combinations of topical and systemic therapies are indicated for patients with stage IIB disease or greater or for patients with refractory stage I disease. [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

Localized mycosis fungoides therapy may include radiotherapy, intralesional steroids, or surgical excision, as well as the following:

-

Extracorporeal photopheresis, alone or in combination with other treatment modalities (eg, IFN-α) [17] : Sézary syndrome, erythrodermic mycosis fungoides

-

Unrelated cord blood transplantation [18] : Mycosis fungoides

-

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Treatment-refractory mycosis fungoides [9]

-

Multiagent chemotherapy: Unequivocal lymph node or systemic involvement, or widespread tumor-stage mycosis fungoides that is refractory to skin-targeted therapies and is not early patch or plaque-stage disease

Topical therapies include topical steroids, topical retinoids, topical chemotherapy, psoralen-enhanced light therapy, and total body electron beam radiation. Systemic therapy includes oral retinoids, recombinant IFN-α, fusion toxins, monoclonal antibodies, single-agent chemotherapy, histone deacetylase inhibitors, and extracorporeal photopheresis.

Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome therapy is based on disease burden and rapidity of progression. [19] Preserve immune response to prevent infection, use immunomodulatory therapy before chemotherapy (unless disease burden or therapeutic failure requires otherwise), and consider combination therapy over monotherapy, particularly systemic immunomodulatory therapy plus skin-directed treatments.

Pharmacotherapy

The following agents are used in the management of CTCL:

-

Antineoplastics (eg, chlorambucil, vorinostat, methotrexate, etoposide, romidepsin, denileukin diftitox, carmustine, mechlorethamine, bexarotene)

-

Immunomodulators (eg, IFN-α 2b)

-

Monoclonal antibody antineoplastics (eg, alemtuzumab)

-

Topical skin products (eg, Imiquimod 5% cream, topical mechlorethamine)

-

Retinoid-like agents (eg, alitretinoin, tazarotene gel)

-

Corticosteroids (eg, prednisone, prednisolone)

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

For patient education information, see Understanding Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Background

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a term that was created in 1979 at an international workshop sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to describe a group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by localization of neoplastic T lymphocytes to the skin. (For lymphomas in general, the skin is actually the second most common extranodal site; gastrointestinal sites are first.) [20, 21, 9, 10, 22]

When the term was first coined, it most often referred to mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome, the most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. [23, 24] Subsequently, however, the many entities that make up the cutaneous T-cell lymphomas were found to differ widely in biologic course, histologic appearance, and, in some cases, immunologic and cytogenetic features and in their response to appropriate treatment (see the images below). (See Pathophysiology, Etiology, Presentation, and Workup.)

Related articles include Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma and Cutaneous Pseudolymphoma.

Classification of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas have been defined in the past by an integration of histologic, biologic, immunologic, and cytogenetic characteristics in two classification systems: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas [25] and the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematologic malignancies. [26] (See Pathophysiology, Etiology, Presentation, and Workup.

A tumor, node, metastases (TNM) classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and its variant Sézary syndrome has also been proposed. [27]

The EORTC classification focused on primary cutaneous lymphomas, which may vary from their nodal counterparts in clinical behavior, prognosis, and appropriate therapeutic approaches. [25] The classification also recognized that, unlike the general group of lymphomas, a histologic diagnosis in a case of cutaneous lymphoma may not be the final diagnosis, but may instead be a differential diagnosis that requires clinicopathologic correlation. (See Prognosis, DDx, Treatment, and Medication.)

The WHO classification included cutaneous lymphomas in the general classification of lymphoma to facilitate the description of clinicopathologic entities in their entirety, reporting common features of disease entities that may present in multiple anatomic sites. [26] The WHO classification allowed oncologists, dermatologists, and pathologists to use a common language.

In 2005, during consensus meetings, representatives of both systems reached an agreement on a new classification system, the WHO-EORTC Classification of Cutaneous Lymphomas which was updated in 2018. (See Table 1, below.) [2, 3]

Table 1. WHO-EORTC Classification of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (Open Table in a new window)

WHO-EORTC Classification |

Frequency (%) |

5-Year Survival Rate (%) |

Indolent Clinical Behavior |

||

Mycosis fungoides |

39 |

88 |

Mycosis fungoides variants and subtypes |

||

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides |

5 |

75 |

Pagetoid reticulosis |

< 1 |

100 |

Granulomatous slack skin |

< 1 |

100 |

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder |

||

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

8 |

95 |

Lymphomatoid papulosis |

12 |

100 |

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

1 |

82 |

Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

2 |

75 |

Aggressive Clinical Behavior |

||

Sézary syndrome |

2% |

36% |

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma |

< 1 |

NDA |

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type |

< 1 |

16 |

Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified |

2 |

15 |

| Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, rare subtypes | ||

| Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma (provisional) | < 1 | 100 |

Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

< 1 |

31 |

Primary cutaneous gamma/delta-positive T-cell lymphoma |

< 1 |

11 |

Source: Adapted from Willemze et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14. [3] EORTC = European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer; NDA = no data available; NK = natural killer; WHO = World Health Organization. |

||

Table 2, below, summarizes various types of cluster designations and their representative cells.

Table 2. Cluster Designations (Open Table in a new window)

CD Type |

Representative Cells |

Also Known As |

CD2 |

T, NK |

Sheep RBC |

CD3 |

T |

|

CD4 |

T subset |

Helper |

CD5 |

T |

|

CD7 |

T, NK |

Prothymocyte |

CD8 |

T subset, NK |

Suppressor |

CD25 |

Active T, B, M |

IL-2R (Tac) |

CD30 |

Active T, B |

Ki-1 |

CD45 |

T subset |

CLA |

CD56 |

NK |

NCAM |

B = B cell; CD = cluster designation; CLA = common leukocyte antigen; IL-2R = interleukin-2 receptor; M = M cell; NCAM = neural cell adhesion molecule; NK = natural killer; RBC = red blood cell; T = T cell; Tac = Tac antigen. |

||

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas with indolent clinical behavior

Mycosis fungoides is not discussed in this subsection but is addressed further on.

Primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorder

The term CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders encompasses entities such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma (primary cutaneous and systemic type) and lymphomatoid papulosis. Although at times pathologically indistinct, these entities are clinically distinct. Thus, clinicopathologic correlation in the management of these disorders is desirable.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), the primary cutaneous type, manifests as a solitary nodule or ulcerating tumor (> 2 cm) in patients without a history of or concurrent mycosis fungoides or lymphomatoid papulosis and without evidence of extracutaneous disease. Extracutaneous dissemination, mainly to regional nodes, occurs 10% of the time.

The disease is multifocal in skin approximately 30% of the time. CD30-positive (75% or more) membrane staining of the large lymphocytes or large clusters of CD30-positive atypical lymphocytes with pleomorphic or multiple nuclei and nucleoli are seen. Numerous mitotic figures can be observed. Unlike systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) staining is usually negative.

A helpful tool for distinguishing cutaneous from systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma is to test for the presence of the t(2;5) translocation. This translocation—although often, but not always, present in cases of systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma—is usually absent in primary cutaneous cases.

Differentiation from lymphomatoid papulosis is not always possible based on histologic criteria. Immunologically, atypical lymphocytes are CD4-positive, with variable loss of CD2, CD3, or CD5.

Staging is required as per other non-Hodgkin lymphomas (eg, using computed tomography [CT] scans, bone marrow examinations, blood work). Patients may experience spontaneous remissions with relapses. If no spontaneous remission occurs, radiation, surgical excision, or both are preferable. Chemotherapy is reserved for patients who have generalized lesions.

Lymphomatoid papulosis manifests as recurrent crops of self-healing, red-brown, centrally hemorrhagic or necrotic papules and nodules on the trunk or extremities; these can evolve to papulovesicular or pustular lesions. These lesions are much smaller than those of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (< 2 cm). The lesions spontaneously resolve in 4-6 weeks, leaving hyperpigmentation or atrophic scars. Variable frequency and/or intensity of outbreaks can occur in different patients. (See the image below.)

A 40-year-old woman complained of a recurrent skin rash, which she described as "bug bites." Skin biopsy results demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate that was CD30 positive. The clinical picture and pathologic findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. This condition has a benign natural history, despite clonal gene rearrangement in some cases. Skin eruptions occur in self-limited crops, which do not require treatment.

A 40-year-old woman complained of a recurrent skin rash, which she described as "bug bites." Skin biopsy results demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate that was CD30 positive. The clinical picture and pathologic findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. This condition has a benign natural history, despite clonal gene rearrangement in some cases. Skin eruptions occur in self-limited crops, which do not require treatment.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is clinically benign, although clonal T-cell gene rearrangement can be demonstrated in 60-70% of cases. Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, or cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma may develop in 20% of cases.

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

In subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, erythematous subcutaneous nodules, which appear in crops, are localized to the extremities or trunk. These lesions may be confused with benign panniculitis and are often accompanied by fever, chills, weight loss, and malaise. They may also be accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome, which may be associated with a rapidly progressive downhill course. Dissemination to extracutaneous sites is rare.

Histologically, early lesions show focally atypical lobular lymphocytic infiltration of the subcutaneous fat that may also be confused with benign panniculitis. Later, infiltration of pleomorphic lymphoid cells into fat, with rimming of individual fat cells by the neoplastic cells, is accompanied by frequent mitoses, karyorrhexis, and fat necrosis. Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis (histiocytes phagocytizing red and white blood cells) can also complicate the histologic picture.

Immunologically, atypical lymphocytes stain positively for CD3 and CD8, with clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gene documented.

At least 2 groups of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma with different histologies, phenotypes, and prognoses can be distinguished. Cases with an alpha/beta-positive T-cell phenotype are usually CD8+, are characterized by recurrent lesions that are restricted to the subcutaneous tissue (with no dermal or epidermal involvement), and tend to run an indolent clinical course. [28, 29]

The WHO-EORTC term subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma refers only to the alpha/beta type. [2] Although affected patients were treated with chemotherapy or radiation in the past, it appears that patients treated with systemic steroids may remain in good clinical control.

A similar-appearing lymphoma with a gamma/delta phenotype is CD8– and CD56+. Histologically, the infiltration may not be limited to the subcutaneous tissue, and the course may be more aggressive. In the WHO-EORTC classification, this lymphoma is considered to be a different entity and is included in the group of cutaneous gamma/delta-positive lymphomas in a provisional category. [2] Clinically, this lymphoma is more aggressive, with dissemination to mucosal and other extranodal sites. [2, 29, 30, 31, 32]

Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder

This condition presents with solitary or localized plaques or tumors in the face, neck, and/or upper trunk area. The disease typically has an indolent course, and spontaneous regression in over 30% of cases has been reported. [33] Lesions that do not resolve spontaneously are treated primarily with intralesional steroids, surgical excision, or, in rare instances, with radiotherapy. Histologically, these lesions show dense, nodular to diffuse dermal infiltrates that consist mainly of CD4+ small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T cells; a small proportion (< 30%) of large pleomorphic cells may be present. [3]

Aggressive subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

In this section, the following are reviewed:

-

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (human T-cell lymphotropic virus [HTLV]–positive)

-

Nasal-type extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma

-

Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified (PTCL-U)

Provisional categories, such as primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma are also discussed. Cutaneous gamma/delta-positive T-cell lymphoma (discussed earlier) also belongs in this category. Sézary syndrome is discussed in the subsection on mycosis fungoides. [34]

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia

Most patients with adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia are those with antibodies to HTLV-1, a retrovirus endemic to southwest Japan, South America, central Africa, and the Caribbean. Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia develops in 1-5% of seropositive individuals, often 20 years after exposure.

In the acute form, cutaneous lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, lytic bone lesions, and infections are observed, along with an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and hypercalcemia. In the chronic and smoldering forms, the skin rash is characterized by papules, nodules, plaques, or erythroderma with pruritus, which can resemble mycosis fungoides histologically and clinically.

Cells with hyperlobate nuclei (in a clover-leaf pattern) infiltrate the dermis and subcutis. Epidermotropism with Pautrier microabscesses can be seen in one third of cases.

Immunologically, the malignant cells are positive for CD2, CD3, and CD5 but negative for CD7; CD4 and CD25 are positive. The T-cell gene rearrangement is clonal, and the HTLV-1 genome is integrated into the neoplastic cells' genome.

Standard treatment with chemotherapy does not appear to affect survival. The use of zidovudine and interferon has been advocated.

The prognosis in patients with adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia is poor, with a 6-month median survival for the acute form and a 24-month median survival for the chronic form.

Nasal-type extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

In nasal-type extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, a disease characterized by small, medium, and large cells, the nasal cavity/nasopharynx and the skin of the trunk and extremities are involved by multiple plaques and tumors (see the image below). These lesions are frequently accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever and weight loss, and an associated hemophagocytic syndrome may be observed.

A 42-year-old woman who had moved to the United States from Peru several year ago presented with an ulcerative lesion on her face near her nose, and destruction of her hard palate. Tissue biopsy revealed NK/T-cell lymphoma. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

A 42-year-old woman who had moved to the United States from Peru several year ago presented with an ulcerative lesion on her face near her nose, and destruction of her hard palate. Tissue biopsy revealed NK/T-cell lymphoma. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

Cutaneous involvement may be primary or secondary. Because both primary involvement and secondary involvement are clinically aggressive and require the same type of treatment, distinction between them seems unnecessary. [29, 35, 36, 37]

This condition is more common in males and geographically is more common in Asia, Central America, and South America.

Dermal and subcutaneous infiltration with invasion of the vascular walls and occlusion of the vessel lumen by lymphoid cells lead to tissue necrosis and ulceration.

The malignant cells are usually CD2 and CD56 positive (NK phenotype), with cytoplasmic, but not surface, CD3 positivity. The cells contain cytotoxic proteins (T-cell intracellular antigen 1 [TIA-1], granzyme B, and perforin). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) tests are commonly positive. Rarely, the cells may have a true cytotoxic T-cell phenotype.

Nasal-type extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is an aggressive disease that requires systemic therapy, although the experience with systemic chemotherapy has generally been poor.

Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified

PTCL-U is a heterogeneous entity that manifests with localized or generalized plaques, nodules, and/or tumors. By definition, this group excludes all 3 provisional categories of PTCLs delineated in the WHO-EORTC classification. [2]

The absence of previous or concurrent patches or plaques consistent with mycosis fungoides differentiates these lesions from classic mycosis fungoides in transformation to diffuse large cell lymphoma.

Pleomorphic infiltration of small/large lymphocytes is observed diffusely infiltrating the dermis. Large, neoplastic T cells are present by greater than 30%. The immunophenotype is generally CD4+. Immunologically, most neoplastic lymphocytes show an aberrant CD4-positive phenotype with clonal rearrangement of T-cell receptor genes. Results from CD30 staining are negative.

Patients with PTCL-U generally have a poor prognosis and should be treated with systemic chemotherapy. The 4-year survival rate approaches 22%. Although a small percentage of patients may undergo spontaneous remission, a more aggressive behavior is more likely.

Staging for systemic lymphoma and multiagent chemotherapy is recommended. If the patient has solitary or localized disease, radiation therapy could be considered as an initial treatment.

Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma

Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma is a clinically aggressive, sometimes disseminated disease that presents as eruptive papules, nodules, and tumors with central ulceration. This entity can also present as superficial patches and/or plaques. Affected patients have typically been treated with anthracycline-based systemic chemotherapy.

Histologically, epidermotropism with invasion and destruction of adnexal skin structures and angiocentricity with angioinvasion can be seen. The malignant cells are CD3- and CD8-positive and contain cytotoxic proteins. Clonal T-cell gene rearrangement is seen. EBV tests are typically negative in primary aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.

Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma

Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a provisional entitiy in the revised 2018 WHO-EORTC classification suggesting an aggressive malignant lyphoma but with indolent clinical behavior. The typical clinical presentation is a solitary, slowly progressive papule or nodule, preferentially located on the ear or less commonly on other acral sites, including the nose and the foot. [3]

Histologically, this entity is characterized by a diffuse infiltrate of medium-sized CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. The atypical cells show a CD3+, CD4−, CD8+, and CD30− T-cell phenotype with variable loss of pan-T-cell antigens (CD2, CD5, CD7). They are positive for TIA-1, but unlike other types of CD8+ CTCLs, are negative for other cytotoxic proteins (granzyme B, perforin). [3]

Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (44%), which has led some authors to use this term synonymously with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is a relatively common clonal expansion of T helper cells and, more rarely, T suppressor/killer cells or NK cells, that usually appears as a widespread, chronic cutaneous eruption.

Mycosis fungoides itself is often an epidermotropic disorder and is characterized by the evolution of patches into plaques and tumors composed of small to medium-sized skin-homing T cells; some (or, rarely, all) of these T cells have convoluted, cerebriform nuclei. (See the images below.)

The term mycosis fungoides was first used in 1806 by Alibert, a French dermatologist, when he described a severe disorder in which large, necrotic tumors resembling mushrooms presented on a patient's skin. Approximately 1000 new cases of mycosis fungoides occur annually in the United States (ie, 0.36 cases per 100,000 population).

This condition is more common in blacks than in whites (incidence ratio = 1.6), and it occurs more frequently in men than in women (male-to-female ratio, 2:1). The most common age at presentation is approximately 50 years; however, mycosis fungoides can also be diagnosed in children and adolescents and apparently has similar outcomes. [38]

Variants of mycosis fungoides that are recognized by WHO/EORTC include the following [2] :

-

Sézary syndrome

-

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

-

Granulomatous slack skin

-

Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease)

Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome accounts for about 5% of all cases of mycosis fungoides. The patient with Sézary syndrome has generalized exfoliative dermatitis or erythroderma and lymphadenopathy, as well as atypical T lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei (more than 1000 per mm3) circulating in the peripheral blood or other evidence of a significant malignant T-cell clone in the blood, such as clonal T-cell gene rearrangement identical to that found in the skin. (See the images below.)

The T-cell gene rearrangement is demonstrated by molecular or cytogenetic techniques and/or an expansion of cells with a malignant T-cell immunophenotype (an increase of CD4+ cells such that the CD4/CD8 ratio is >10, and/or an expansion of T cells with a loss of one or more of the normal T-cell antigens [eg, CD2, CD3, CD5]). The circulating malignant cells tend to be CD7 and CD26 negative.

Although Sézary syndrome may be part of a continuum from erythrodermic mycosis fungoides, the WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphoma considers its behavior "aggressive." [2]

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides manifests as follicular papules, patchy alopecia, and comedolike lesions, particularly in the head and neck area. An infiltration of atypical lymphocytes is observed in the epithelium of hair follicles, and mucinous degeneration of the hair follicles (follicular mucinosis) may be seen. Topical treatments may not be effective because of the depth of infiltration.

Pagetoid reticulosis

Pagetoid reticulosis, or Woringer-Kolopp disease, manifests with a solitary, asymptomatic, well-defined, red, scaly patch or plaque on the extremities that may slowly enlarge. A heavy, strictly epidermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes is observed. The prognosis is excellent, with radiation therapy or surgical excision being the treatment of choice.

The term pagetoid reticulosis should be restricted to the localized type and should not be used to describe the disseminated type (Ketron-Goodman type). [39]

Granulomatous slack skin

Granulomatous slack skin is a condition characterized by the slow development of pendulous, lax skin, most commonly in the areas of the axillae and groin. Histologically, a granulomatous infiltration is seen, accompanied by multinucleate giant cells with elastophagocytosis and an almost complete loss of elastin in the dermis (demonstrated by elastin stain). Disease recurrence is common after surgical intervention. Radiation may be of use, but experience with it in this disease is limited. One third of patients have been reported to have concomitant Hodgkin lymphoma or mycosis fungoides.

Granulomatous cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are rare, so limited data on their clinicopathologic and prognostic features are available. [40] Patients with either granulomatous mycosis fungoides or granulomatous slack skin display overlapping histologic features. The development of bulky skin folds in granulomatous slack skin differentiates this condition clinically from granulomatous mycosis fungoides.

Pathophysiology

Of all primary cutaneous lymphomas, 65% are of the T-cell type. The most common immunophenotype is CD4 positive. The malignant T lymphocytes of CTCL are characterized by a state of constitutive activation and clonal expansion. These malignant cells are resistant to apoptosis mediated by Fas, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta).

An increase in CTCL malignant cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes result in a decrease in healthy CD4+, CD8+ and NK cells. Malignant CTCL cells often exhibit a Th2 cytokine profile with production of IL-4, IL-5, and/or IL-13, which inhibits Th1-type immunity. CTCL cells can also produce IL-10 and TGF-beta, which are T regulatory (Treg) cytokines that inhibit host cell-mediated immunity. [41]

Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is a malignant lymphoma characterized by the expansion of a clone of CD4+ (or helper) memory T cells (CD45RO+) that normally patrol and home in on the skin. [21] The malignant clone frequently lacks normal T-cell antigens such as CD2, CD5, or CD7.

The normal and malignant cutaneous T cells home in on the skin through interactions with dermal capillary endothelial cells. Cutaneous T cells express cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA), an adhesion molecule that mediates tethering of the T lymphocyte to endothelial cells in cutaneous postcapillary venules via its interaction with E selectin. [42] Further promoting the proclivity of the cutaneous T cell to home in on the skin is the release by keratinocytes of cytokines, which infuse the dermis, coat the luminal surface of the dermal endothelial cells, and upregulate the adhesion molecules in the dermal capillary endothelial lumen, which react to CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) found on cutaneous T cells.

Extravasating into the dermis, the cells show an affinity for the epidermis, clustering around Langerhans cells (as seen microscopically as Pautrier microabscesses). However, the malignant cells that adhere to the skin retain the ability to exit the skin via afferent lymphatics. They travel to lymph nodes and then through efferent lymphatics back to the blood to join the circulating population of CLA-positive T cells.

Thus, mycosis fungoides is fundamentally a systemic disease, even when the disease appears to be in an early stage and clinically limited to the skin.

Etiology

The primary etiologic mechanisms for the development of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (eg, mycosis fungoides) have not been elucidated. Mycosis fungoides may be preceded by a T-cell–mediated chronic inflammatory skin disease, which may occasionally progress to a fatal lymphoma. Karyotypic analysis of cutaneous and blood lymphocytes has shown several genetically aberrant T-cell clones in the same patient.

A genotraumatic T cell is one with a tendency to develop numerous clonal chromosomal aberrations. Normal T lymphocytes show apoptosis during in vitro culturing, whereas genotraumatic ones have the ability to develop clonal chromosomal aberrations to become immortalized. This concept implies genetic instability followed by T-cell proliferation. Successive cell divisions of a genotraumatic T-cell clone may produce multiple and complex chromosomal aberrations. Some may reprogram the genotraumatic cells to apoptosis, whereas 1 or more may produce the phenotypic alterations of malignancy if not eliminated in vivo.

Thus, one hypothesis is that the development of genotraumatic T lymphocytes is involved in the etiopathogenesis and the progression of mycosis fungoides. It would also predict that each patient would likely have a unique malignant clone, which, in fact, has been found to be the case.

Environmental factors

Chemical, physical, and microbial irritants have been discussed as causes for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma or mycosis fungoides, but evidence related to an etiology is not convincing. [30] They may play the role of a persistent antigen, which, in a stepwise process, leads to an accumulation of mutations in oncogenes, suppressor genes, and signal-transducing genes. [32] Cutavirus, a recently discovered parvovirus, has been detected in a proportion of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/mycosis fungoides skin samples, suggesting a possible etiologic role. [43] Various theories also implicate occupational or environmental exposures (eg, Agent Orange).

Studies have linked cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with the cutaneous microbiome, most notably Staphylococcus aureus. Skin colonization by S aureus could be involved in the hyperactivation of the STAT3 inflammatory pathway and in the overproduction of interleukin-17, which may promote the development of more aggressive and advanced forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. [44]

In addition, research has suggested a relationship between alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the development of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Studies have shown a decrease in the taxonomic variability of the intestinal microbiome and an increase in certain genera such as Prevotella in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Those alterations may increase systemic cytokine release, promoting hyperactivation of STAT3 in the skin. [44]

Epidemiology

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has a worldwide distribution; some studies have identified a higher prevalence of the disease in industrial populations (eg, among workers who use machine cutting oils). The incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States was reported to be 6.4 persons per million population annually (for the overall, age-adjusted incidence) between 1973 and 2002, with the disease’s incidence increasing over that time period. [45]

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia is endemic in areas with a high prevalence of HTLV-1 infection, such as southwest Japan, the Caribbean islands, South America, and parts of central Africa. This disease occurs in 1-5% of seropositive individuals after more than 2 decades of viral persistence. [46]

Nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma, which is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, is more common in Asia, Central America, and South America.

A study in Kuwait found that the annual incidence rate of mycosis fungoides there was 0.43 case per 100,000 persons. [47]

Race-, sex-, and aged-related demographics

In the United States, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is more common among persons of sub-Saharan African lineage than among those of European background, in a ratio of approximately 2:1. In Kuwait, a study found that the annual incidence rate of mycosis fungoides was significantly higher among Arabs than among non-Arab Asians. [47]

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has a sex predilection, being more common in men than women by a ratio of approximately 2:1. [47]

Most patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are middle-aged or elderly. Sézary syndrome, for example, occurs almost exclusively in adults. Many patients have had a poorly defined form of dermatitis for many years prior to the onset of the disease. In a significant proportion of cases, the onset of the disease, or of a dermatitic precursor of the disease, occurs in childhood.

However, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is exceedingly rare in children younger than 10 years, and in such cases it does not show a male predominance; one series even reported a strong female predilection. Similar to adult patients, most children present in stage IA or IB and have a good to excellent prognosis with treatment, although cases progressing to plaque, tumor-stage disease, and death have been reported.

Some patients with limited mycosis fungoides are described as having Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). These patients are usually middle-aged, with an age distribution in one series ranging from 13-68 years and with a mean age of 55 years.

Prognosis

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are incurable conditions in most patients, with the exception of those with stage IA disease.

Mortality and prognosis are related to the disease stage at diagnosis, as well as to the type and extent of skin lesions and the whether or not extracutaneous disease is present, as demonstrated by the following [2, 48] :

-

Patients diagnosed with stage IA mycosis fungoides (patch or plaque skin disease limited to < 10% of the skin surface area) who undergo treatment have an overall life expectancy similar to age-, sex-, and race-matched controls (10-year survival rate of 97-98%)

-

Patients who have stage IIB disease with cutaneous tumors have a median survival rate of 3.2 years (10-year survival rate of 42%)

-

Patients who have stage III disease (generalized erythroderma) have a median survival rate of 4-6 years (10-year survival rate of 83%)

-

Patients with extracutaneous disease stage IVA (lymph nodes) or stage IVB (viscera) have a survival rate of less than 1.5 years (10-year survival rate of 20% for patients with histologically documented lymph node involvement)

Patients with effaced lymph nodes, visceral involvement, and transformation to large T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course and usually die of systemic involvement or infections.

Blood eosinophilia at baseline may also serve as a prognostic factor in patients with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. [49]

Univariate analysis has shown that the following factors are also associated with reduced survival and increased risk of disease progression [48] :

-

Increased age

-

Male sex

-

Increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

An analysis of 20-year trends reporting on incidence and associated mortality of patients with mycosis fungoides showed a decline in the mortality rate in the United States, perhaps related to increased recognition and earlier diagnosis of the disease. [50] The overall mortality rate is 0.064 per 100,000 persons; however, the mortality rate widely varies depending on the stage of disease at diagnosis.

Sézary syndrome

Late-stage mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome is associated with declining immunocompetence. [51] Death most often results from systemic infection, especially with Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. [52] Secondary malignancies, such as higher-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, colon cancer, and cardiopulmonary complications (eg, high output failure, comorbid cardiopulmonary disease) also contribute to mortality.

Median survival for patients with Sézary syndrome has been reported to be 2-4 years, [53] although the median survival was 2.9 years among patients defined by 2011 criteria for the disease. [19] The disease-specific 5-year survival rate has been reported to be 24%.

Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides

The prognosis associated with folliculotropic mycosis fungoides is worse than that for classic patch- and plaque-stage mycosis fungoides and corresponds more closely with tumor-stage disease (stage IIB). For this reason, some authors have proposed that the disorder be staged with tumor-stage disease (stage IIB). Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides reportedly has a disease-specific 5-year survival rate of approximately 70-80%. [54]

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

In patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, the clinical subtype is the main prognostic factor. Survival in persons with acute or lymphomatous variants is poor, ranging from 2 weeks to more than 1 year. Chronic and smoldering forms have a more protracted clinical course and a longer survival period, but transformation into an acute phase with an aggressive course may occur. [46, 55]

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (with a CD8+, alpha/beta+ T-cell phenotype) tends to have a protracted clinical course with recurrent subcutaneous nodules but without extracutaneous dissemination or the development of a hemophagocytic syndrome. [29] The 5-year survival rate for such patients may be greater than 80%.

Unilesional pagetoid reticulosis

Unilesional pagetoid reticulosis progresses slowly. Patients usually have an excellent prognosis.

PTCL-U

Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified (PTCL-U), is associated with a poor prognosis. The 5-year survival rate is less than 20%, [56] regardless of whether the disease manifests with solitary/localized lesions or generalized skin lesions. [57]

Nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma

Nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma manifesting in the skin is highly aggressive, and patients have a median survival period of less than 12 months. [58, 59] The most important factor in predicting a poor outcome is the initial presence of extracutaneous involvement. Patients first seen with only cutaneous involvement had a median survival of 27 months, compared with months for patients presenting with cutaneous and extracutaneous disease. [59]

CD30+, CD56+ patients seem to have a better prognosis, possibly being examples of cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma with coexpression of CD56. [60]

Granulomatous disease

Granulomatous cutaneous T-cell lymphomas tend to be therapy resistant, with a slowly progressive course that is apparently worse than that of classic nongranulomatous mycosis fungoides. [40]

Provisional entities

Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder is associated with a favorable prognosis, with an estimated 5-year disease-free survival rate of 100%. [3] Patients first seen with solitary or localized skin lesions tend to have an excellent prognosis.

Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma often has an aggressive clinical course, and patients have a median survival period of 32 months. [39]

Cutaneous gamma/delta-positive T-cell lymphoma patients tend to have aggressive disease resistant to multiagent chemotherapy and/or radiation, with a median survival in 1 study of only 15 months. [61] A trend toward decreased survival was noted for patients with subcutaneous fat involvement, in comparison with patients who had epidermal or dermal disease only.

Primary cutaneous acral CD8+ T-cell lymphoma carries an excellent prognosis. Skin lesions can easily be treated with surgical excision or radiotherapy. Cutaneous relapses may occur, but dissemination to extracutaneous sites is very rare. [3]

Complications

Potential complications of mycosis fungoides include the following:

-

Infection, particularly from indwelling intravenous catheters or from lymph node biopsy sites

-

High-output cardiac failure

-

Anemia of chronic disorders

-

Edema

-

Secondary malignancies - Eg, skin cancer, melanoma, colon cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas

-

Patch-stage mycosis fungoides.

-

Plaque-stage mycosis fungoides.

-

A 40-year-old woman complained of a recurrent skin rash, which she described as "bug bites." Skin biopsy results demonstrated an atypical lymphoid infiltrate that was CD30 positive. The clinical picture and pathologic findings were consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. This condition has a benign natural history, despite clonal gene rearrangement in some cases. Skin eruptions occur in self-limited crops, which do not require treatment.

-

Erythroderma of Sézary syndrome.

-

Nail changes of Sézary syndrome.

-

Electron micrograph of a Sézary cell.

-

Tumor-stage mycosis fungoides.

-

Tumor-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

-

Patch-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Courtesy of Jeffrey Meffert, MD.

-

Plaque-stage parapsoriasis.

-

Patch-stage mycosis fungoides progressing to plaque stage, with cutaneous cigarette-paper appearance evident.

-

Partially confluent, erythematous plaques in advancing mycosis fungoides.

-

Close-up view of advancing plaque-stage mycosis fungoides with partially confluent, erythematous plaques.

-

Early patch-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

-

Hypopigmented cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Courtesy of Jeffrey Meffert, MD.

-

Hypopigmented cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Courtesy of Jeffrey Meffert, MD.

-

Nodular mycosis fungoides.

-

Middle-aged woman with mycosis fungoides showing ulceration and marked depigmentation of advanced disease.

-

Middle-aged woman with mycosis fungoides showing ulceration and marked depigmentation of advanced disease.

-

Middle-aged woman with mycosis fungoides showing ulceration and marked depigmentation of advanced disease.

-

Middle-aged woman with mycosis fungoides showing ulceration and marked depigmentation of advanced disease.

-

Mycosis fungoides with large, atypical T lymphocytes in the epidermis and dermis.

-

Mycosis fungoides with an epidermal nest of large, atypical T cells displaying bizarre, convoluted nuclei surrounded by a clear space (Pautrier microabscess).

-

A 42-year-old woman who had moved to the United States from Peru several year ago presented with an ulcerative lesion on her face near her nose, and destruction of her hard palate. Tissue biopsy revealed NK/T-cell lymphoma. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.