Practice Essentials

The most common disease affecting the vertebral artery is atherosclerosis. Less commonly, the extracranial vertebral arteries can be affected by pathologic processes such as trauma, fibromuscular dysplasia, Takayasu disease, osteophyte compression, dissections, and aneurysms. True extracranial aneurysms are virtually always found in the setting of a connective tissue disorder (CTD), whereas false aneurysms may or may not be related to a CTD but usually follow arterial dissection.

Crawford and coworkers first described the technique of trans-subclavian endarterectomy of the vertebral artery. [1] Transposition of the proximal vertebral artery to the common carotid was described by Clark and Perry in 1966 through a similar approach. [2] During the 1970s, the saphenous vein was first used to bypass vertebral artery origin stenoses. [3] Eventually, transposition techniques were found to be superior solutions for proximal vertebral disease and have supplanted endarterectomy and bypass as the reconstruction options of choice.

The approach to the distal vertebral artery was first described by Matas and Henry and was used for the treatment of traumatic injury. [4, 5] During the late 1970s, venous bypass and skull base transposition procedures to revascularize the distal vertebral artery were developed using a similar approach. [6, 7, 8]

Etiology and presentation

Arterial-to-arterial emboli can arise from atherosclerotic lesions, from intimal defects caused by extrinsic compression or repetitive trauma, and rarely from fibromuscular dysplasia, aneurysms, or dissections. Although fewer patients suffer from embolic phenomena than those with hemodynamic ischemia, actual infarctions in the vertebrobasilar distribution are most often the result of embolic events. Patients with embolic ischemia often develop multiple and multifocal infarcts in the brain stem, cerebellum, and, occasionally, posterior cerebral artery territory. Patient presentation is dissimilar to those with hemodynamic symptoms.

Patients who experience emboli have varied presentations. In patients with posterior circulation ischemia secondary to microembolism and appropriate lesions in a vertebral artery, the potential source of the embolus needs to be eliminated regardless of the status of the contralateral vertebral. These patients are considered candidates for surgical or endoluminal correction of the offending lesion regardless of the condition of the contralateral vertebral artery. With the exception of the patient presenting with a vertebral artery aneurysm, surgical or endovascular intervention is not indicated in asymptomatic patients who harbor suspicious radiographic findings.

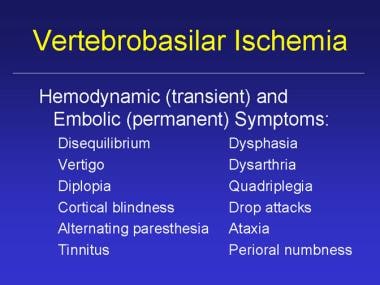

Ischemia affecting the temporo-occipital areas of the cerebral hemispheres or segments of the brain stem and cerebellum characteristically produces bilateral symptoms. The classic symptoms of vertebrobasilar ischemia are dizziness, vertigo, diplopia, perioral numbness, alternating paresthesia, tinnitus, dysphasia, dysarthria, drop attacks, ataxia, and homonymous hemianopsia. (See the image below.)

When patients present with 2 or more of these symptoms, vertebrobasilar ischemia is likely the cause. Nevertheless, symptoms associated with posterior circulation ischemia are often dismissed as nonspecific findings. Because of the often vague nature of patient presentation, clinicians may be reluctant to pursue a pathologic diagnosis or to recommend treatment for potentially correctable vertebral artery lesions.

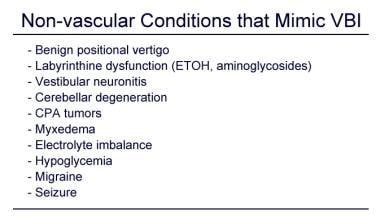

Numerous medical conditions may cause or mimic vertebrobasilar ischemia, thus confounding the selection of patients in need of posterior circulation treatment. These include inappropriate use of antihypertensive medications, cardiac arrhythmias, anemia, brain tumors, benign vertiginous states, basilar artery migraine, and postsubarachnoid hemorrhage vasospasm. (See the image below.)

In general, the ischemic mechanisms can be broken down into those that are hemodynamic and those that are embolic. Hemodynamic symptoms occur as a result of transient "end-organ" (brainstem, cerebellum, and/or occipital lobes) hypoperfusion and can be precipitated by postural changes or transient reduction in cardiac output. Ischemia from hemodynamic mechanisms rarely results in tissue infarction. Symptoms from hemodynamic mechanisms tend to be short lived, repetitive, almost predictable, and more of a nuisance than a danger.

For hemodynamic symptoms to occur in direct relation to the vertebrobasilar arteries, significant occlusive pathology must be present in both of the paired vertebral vessels or in the basilar artery. In addition, compensatory contribution from the carotid circulation via the Circle of Willis must be incomplete. Alternatively, hemodynamic ischemic symptoms may follow proximal subclavian artery occlusion and the syndrome of subclavian/vertebral artery steal.

In later years of life, vertebral artery stenosis is a common arteriographic finding, and dizziness is a common complaint. The presence of both cannot necessarily be assumed to have a cause-and-effect relationship. Surgical reconstruction is not indicated in an asymptomatic patient with stenotic or occlusive vertebral lesions. These patients are well compensated, usually from the carotid circulation through the circle of Willis.

The minimal anatomic requirement to justify vertebral artery reconstruction for a patient with hemodynamic symptoms is (1) stenosis of more than 60% diameter in both vertebral arteries if both are patent and complete or (2) the same degree of stenosis in the dominant vertebral artery if the opposite vertebral artery is hypoplastic, ends in a posteroinferior cerebellar artery (PICA), or is occluded. A single, normal vertebral artery is sufficient to adequately perfuse the basilar artery, regardless of the patency status of the contralateral vertebral artery.

Embolic causes of vertebrobasilar ischemia may not be as well recognized. As many as one third of vertebrobasilar ischemic episodes are caused by distal embolization from plaques or mural lesions of the subclavian, vertebral, and/or basilar arteries. [6, 8] Arterial-to-arterial emboli can arise from atherosclerotic lesions, from intimal defects caused by extrinsic compression or repetitive trauma, and rarely from fibromuscular dysplasia, aneurysms, or dissections. Although fewer patients suffer from embolic phenomena than hemodynamic ischemia, actual infarctions in the vertebrobasilar distribution are most often the result of embolic events. Patients with embolic ischemia often develop multiple and multifocal infarcts in the brain stem, cerebellum, and, occasionally, posterior cerebral artery territory. Patient presentation is dissimilar to those with hemodynamic symptoms.

Patients who experience emboli have varied presentations. In patients with posterior circulation ischemia secondary to microembolism and appropriate lesions in a vertebral artery, the potential source of the embolus needs to be eliminated regardless of the status of the contralateral vertebral artery. These patients are considered candidates for surgical or endoluminal correction of the offending lesion regardless of the condition of the contralateral vertebral artery. With the exception of the patient presenting with a vertebral artery aneurysm, surgical or endovascular intervention is not indicated in asymptomatic patients who harbor suspicious radiographic findings.

Treatable vertebral artery disease may be underdiagnosed when compared to carotid disease. Patients with vertebrobasilar ischemia do represent a significant cohort of patients. Twenty-five percent of all transient ischemic attacks and ischemic strokes involve areas of the brain supplied by the vertebrobasilar circulation. For patients who experience vertebrobasilar transient ischemic attacks, disease identified in the vertebral arteries portends a 30-35% risk for stroke over a 5-year period. [9, 10, 11] Medical refractory disease of the vertebrobasilar system carries a 5-11% risk of stroke or death at 1 year. [12] Consequently, mortality associated with a posterior circulation stroke is high, ranging from 20-30%, and this disease entity should not be ignored. [13, 14, 15, 16]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of vertebrobasilar ischemia begins with an accurate assessment of the presenting symptom complex. A 20 mm Hg systolic pressure drop on rapid standing is the criterion for a diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension causing low-flow in the vertebrobasilar system. An ambulatory 24-hour electrocardiogram (Holter monitor) should be performed in patients with hemodynamic ischemia because arrhythmias are a common cause of symptomatology due to decreased cardiac output associated with the arrhythmia. Echocardiography is useful to rule out significant valvular pathology that could cause brainstem hypoperfusion.

Once a suspicion of vertebrobasilar ischemia has been entertained, only a few studies clearly ascertain vertebral anatomy.

Duplex ultrasonography is an excellent tool for detecting lesions in the carotid artery but has significant limitations in detecting vertebral artery pathology. The usefulness of duplex ultrasound lies in its ability to confirm reversal of flow within the vertebral arteries and to detect changes in flow velocity consistent with proximal stenosis. It can also diagnose great vessel pathology and confirm subclavian steal. [17] There is great interest in ultrasound imaging of the vertebral artery for stent placement to treat vertebral artery stenosis. Changes in waveforms are helpful in detecting the pathologic processes that involve the proximal and distal neurovascular circulation. [18, 19, 20]

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction and maximum intensity projection (MIP) can provide full imaging of the vessels, including the supra-aortic trunks, the carotid and vertebral arteries, and the circle of Willis. MRI provides accurate and noninvasive visualization of the vertebral and basilar arteries and surrounding structures of the posterior fossa. Transaxial MRI can detect acute and chronic posterior fossa infarcts, which is enhanced by MRA with 3D reconstructions and MIP imaging,

Selective subclavian and vertebral angiography remains the best test for preoperative evaluation of patients with vertebrobasilar ischemia. Catheter angiography may be necessary to prove pathology. Patients with suspected vertebral artery compression, usually by osteophytes, should undergo dynamic angiography.

Treatment

With appropriate diagnosis and surgical correction, complete resolution of hemodynamic and embolic symptoms can be achieved. Location of disease dictates the type of surgical reconstruction required. Patients with symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia who cannot be treated with surgery or endoluminal therapy may be treated with antiplatelet agents or long-term anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis.

Using stents for treating a lesion of the distal V3 segment is an option for the prevention of stroke. However, the relatively small diameter of a hypoplastic vertebral artery and the tortuous course and atherosclerotic stenosis in V1 or V2 have been known to be obstacles to conventional vertebral stenting. [21]

The main option for treating ostial lesions (V1 segment) is transposition of the proximal vertebral artery onto the common carotid artery.

Elective surgical reconstruction is very rarely undertaken within the V2 segment; however, ligation (at the C1-C2 level) and bypass to the distal (V3 segment) vertebral artery may be indicated. Extrinsic lesions can be corrected to relieve kinking or compression of the artery. The most common indication for exposure of the V3 segment of the artery is for control of hemorrhage. An alternative for traumatic injuries to the V2 segment includes coil embolization.

Reconstruction of the distal (V3 segment) vertebral artery is usually performed at the C1-C2 level. The techniques most often used to reconstruct the distal vertebral artery at this level include (1) saphenous vein bypass from the common carotid, subclavian, or proximal vertebral artery; (2) transposition of the external carotid or hypertrophied occipital artery to the distal vertebral; and (3) transposition of the distal vertebral artery to the side of the distal internal carotid artery. [22]

More distal pathology can be accessed surgically above the level of the transverse process of C1. Surgical exposure at the suboccipital segment requires resection of the C1 transverse process and part of its posterior arch. Reconstruction at this level is limited to saphenous vein bypass from the distal internal carotid artery.

The use of drug-eluting balloons (DEB) in peripheral artery disease has shown a reduction in the number of stents as well as their length after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA). Endovascular treatment is the first therapeutic option for subclavian artery occlusive lesions and generally provides positive results. [23]

Pathophysiology

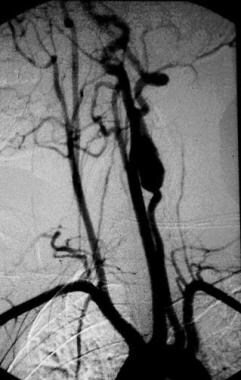

The most common disease affecting the vertebral artery is atherosclerosis. Less common pathologic processes include trauma, fibromuscular dysplasia, Takayasu disease, osteophyte compression, dissections, and aneurysms. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency is an inadequate flow of blood through the posterior circulation of the brain, which is supplied by the 2 vertebral arteries that merge to form the basilar artery. The vertebrobasilar vasculature supplies blood flow to areas of the brain such as the brainstem, thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, occipital and medial temporal lobes. [24, 25, 26] (See the images below.)

Indications for Surgery

Once the diagnosis of vertebrobasilar ischemia has been confirmed with appropriate imaging, surgical correction may be considered. The mere presence of vertebral artery stenosis in an asymptomatic patient is rarely an indication for surgery. Surgical reconstruction is based on the specific etiology. The indication for surgery in patients with hemodynamic symptoms depends on the ability to demonstrate insufficient blood flow to the basilar artery.

A single normal-caliber vertebral artery can supply sufficient blood flow into the basilar artery regardless of the status of the contralateral vessel. In this particular subset of patients, surgical intervention is indicated only in the presence of a severely stenotic (>75%) vertebral artery and an equally diseased or occluded contralateral vessel. Surgical reconstruction is not indicated in an asymptomatic patient with the aforementioned radiographic findings because these patients are well compensated from the carotid circulation through the posterior communicating vessels.

In contrast, patients with symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia due to emboli are candidates for surgical correction of the offending lesion regardless of the condition of the contralateral vertebral artery. As in the hemodynamic group, surgical intervention is not indicated in asymptomatic patients with suggestive radiographic findings.

In a study by Min Wu et al of predictors of 3-month and 1-year mortality In patients with vertebrobasilar artery occlusion who received endovascular treatment, the 24-hr Glasgow Coma Scale score and mechanical ventilation were found to be common predictors of 3-month and 1-year mortality, and intracranial hemorrhage was an additional predictor of 1-year mortality. [27]

Relevant Anatomy

The posterior circulation, or vertebrobasilar system, supplies blood to the brainstem, cerebellum, and occipital lobes via paired vertebral arteries. The vertebrals converge beyond the base of the skull and form the basilar artery at the base of the pons. [28, 26] The vertebral artery is arbitrarily segmented into the following 4 parts:

-

V1 extends from the origin of the vertebral artery, where it arises from the subclavian artery up to the point at which the artery enters the C6 transverse process. The origin of the vertebral from the subclavian is the most common site for a hemodynamically significant atherosclerotic stenosis.

-

V2 lies within the cervical transverse processes (C6-C2) and is buried deep within intertransversarium muscle. The V2 segment is the site of a wide variety of disorders. External compression is most likely to occur in this segment because of osteophytes, the edge of the transverse foramina, or the intervertebral joints. Positional changes, such as rotation or extension of the neck, usually trigger compression of the vertebral artery in this segment. The V2 segment is also the most frequent site of true aneurysmal degeneration, fibromuscular diseases, and embolizing atherosclerotic plaques.

-

V3 is the extracranial segment that lies between the transverse process of the C2 and the base of the skull, where the artery enters the foramen magnum and penetrates the dura matter. This segment is infrequently affected by atherosclerosis but is vulnerable to direct trauma and stretch injuries.

-

V4 is the intracranial portion beginning at the atlanto-occipital membrane and terminating at the formation of the basilar artery. The V4 segment is devoid of adventitia; as such, open or endovascular intervention in this segment should be approached with extreme caution.

Dissections commonly occur at the base of the skull where V3 transitions to V4. This likely occurs because, here, the vertebrae allow for maximal cervical mobility near where the artery loses some of its integrity.

The anterior spinal artery arises from branches off each of the vertebral arteries just before they converge to form the basilar artery. Pontine and cerebellar arteries arise from the basilar artery before it bifurcates into the paired posterior cerebral arteries. One vertebral artery may end in a posterior inferior cerebellar artery rather than join the basilar artery.

The location of disease will dictate the type of surgical reconstruction that is required. With rare exceptions, most reconstructions of the vertebral artery are performed to treat an origin stenosis (V1 segment) or stenosis, dissection, or occlusion of its intraspinal component (V2 and V3 segments).

Contraindications

As discussed previously, a single normal-caliber vertebral artery can supply sufficient blood flow into the basilar artery regardless of the status of the contralateral vessel. In this particular subset of patients, surgical intervention is indicated only in the presence of a severely stenotic (>75%) vertebral artery and an equally diseased or occluded contralateral vessel. Surgical reconstruction is not indicated in an asymptomatic patient with the aforementioned radiographic findings, because these patients are well compensated from the carotid circulation through the posterior communicating vessels.

Patients with symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia who are not amenable to surgery or investigational endoluminal therapy may be treated medically with long-term anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis.

-

True vertebral artery aneurysm (9 cm).

-

Magnified view of MRI of the brain. The arrow denotes the site of a posterior fossa infarction.

-

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with 3-dimensional reconstruction of the extracranial and intracranial vertebral and carotid arterial system. The arrow denotes the right vertebral artery.

-

Selective angiography of the left subclavian artery demonstrating collateral flow to a patent distal left vertebral artery via the thyrocervical trunk.

-

An arteriogram following a proximal vertebral to carotid artery transposition.

-

An arteriogram demonstrating aneurysmal degeneration of a left vertebral artery in the V2 segment.

-

Selective angiogram of a right vertebral artery pseudoaneurysm.

-

Symptoms of vertebrobasilar ischemia.

-

Anastomosis.

-

Vertebral stent fracture with in-stent restenosis.

-

Nonischemic conditions that may mimic vertebrobasilar ischemia.