Practice Essentials

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder that occurs most commonly because of the presence of stones in the gallbladder or an obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones arising from the gallbladder (cholelithiasis). Uncomplicated cholecystitis has an excellent prognosis; the development of complications such as gangrene or perforation renders the prognosis less favorable.

Signs and symptoms

The most common presenting symptom of acute cholecystitis is upper abdominal pain. The following characteristics may be reported:

-

Pain may radiate to the right shoulder or scapula

-

Pain frequently begins in the epigastric region and then localizes to the right upper quadrant (RUQ)

-

Pain may initially be "colicky" (it is NOT a true colic) but almost always becomes constant

-

Nausea and vomiting are generally present, and fever may be noted

Patients with acalculous cholecystitis may present with fever and sepsis alone, without the history of pain.

The physical examination may reveal the following:

-

Fever, tachycardia, and signs of peritoneal irritation (eg, tenderness in the RUQ or epigastric region, often with guarding or rebound)

-

Palpable, tender gallbladder or fullness of the RUQ (30%-40% of patients)

-

Jaundice (~15% of patients)

The absence of physical findings, however, does not rule out the diagnosis of cholecystitis.

Acute cholecystitis may present differently in special populations, as follows:

-

Elderly (especially diabetics) – May present with vague symptoms and without many key historical and physical findings (eg, pain and fever), with localized tenderness being the only presenting sign; may progress to complicated cholecystitis rapidly and without warning

-

Children – May present without many of the classic findings; those at higher risk for cholecystitis include patients with sickle cell disease, serious illness, a requirement for prolonged total parenteral nutrition (TPN) hemolytic conditions, or congenital biliary anomalies

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory tests are not always reliable, but the following findings may be diagnostically useful:

-

Leukocytosis with a left shift may be observed

-

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels may be elevated in cholecystitis or with common bile duct (CBD) obstruction

-

Bilirubin assays may reveal evidence of CBD obstruction

-

Amylase/lipase assays are used to assess for acute pancreatitis; amylase may also be mildly elevated in cholecystitis

-

Alkaline phosphatase level may be elevated (25% of patients with cholecystitis)

-

Urinalysis is used to rule out pyelonephritis and renal calculi

-

Transient mild CBD obstruction may be caused by inflammatory edema in the Calot triangle and the hepatoduodenal ligament.

Diagnostic imaging modalities that may be considered include the following:

-

Plain X-ray of the abdomen

-

Ultrasonography (US)

-

Computed tomography (CT)

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

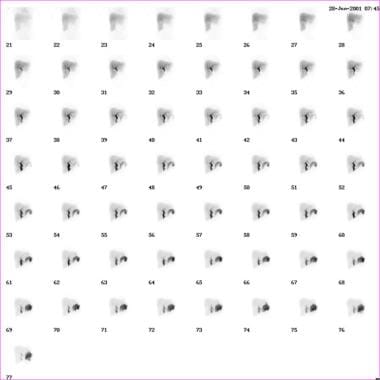

Hepatobiliary isotope scintigraphy (see the image below)

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria offer the following imaging recommendations [1] :

-

US is the preferred initial imaging test for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis; hepatobiliary isotope scintigraphy is the preferred alternative.

-

CT scanning is a secondary imaging test that can identify extrabiliary disorders and complications of acute cholecystitis when US has not yielded a clear diagnosis.

-

CT scanning with intravenous (IV) contrast medium is useful in diagnosing acute cholecystitis in patients with nonspecific abdominal pain.

-

MRI, often with IV gadolinium-based contrast medium, is also a possible secondary choice for confirming a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

-

MRI is a useful alternative to CT scanning for eliminating radiation exposure in pregnant women .

-

Contrast agents should not be used in patients with renal dysfunction unless absolutely necessary.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of cholecystitis depends on the severity of the condition and the presence or absence of complications.

In cases of mild, uncomplicated acute cholecystitis, outpatient treatment may be appropriate. The following medications may be useful in this setting:

-

Levofloxacin and metronidazole for antibiotic coverage against the most common organisms

-

Antiemetics (eg, promethazine or prochlorperazine) to control nausea and prevent fluid and electrolyte disorders

-

Analgesics (eg, oxycodone/acetaminophen)

In acute cholecystitis, the initial treatment includes bowel rest, IV hydration, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, analgesia, and IV antibiotics. Antibiotic coverage should be for gram-negative enteric flora and anaerobes if biliary tract infection is suspected. Options include the following:

-

(Sanford Guide) Piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, or meropenem; in severe life-threatening cases, imipenem-cilastatin

-

Alternative regimens – Third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole

-

Emesis can be treated with antiemetics and nasogastric suction

-

Because of the rapid progression of acute acalculous cholecystitis to gangrene and perforation, early recognition and intervention are required.

-

Supportive medical care should include restoration of hemodynamic stability

-

Daily stimulation of gallbladder contraction with IV cholecystokinin (CCK) may help prevent formation of gallbladder sludge in patients receiving TPN

Surgical and interventional procedures used to treat cholecystitis include the following:

-

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (standard of care for surgical treatment of acute cholecystitis)

-

Percutaneous gallbladder drainage/cholecystostomy (PCC)

-

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural cholecystostomy

-

Endoscopic gallbladder drainage

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Cholecystitis is defined as an inflammation of the gallbladder that occurs most commonly because of the presence of stones in the gallbladder or an obstruction of the cystic duct from cholelithiasis. Ninety percent of cases involve stones in the gallbladder (ie, calculous cholecystitis), with the other 10% of cases representing acalculous cholecystitis. [2]

Risk factors for cholecystitis mirror those for cholelithiasis and include increasing age, female sex, certain ethnic groups, obesity or rapid weight loss, drugs, and pregnancy. Although bile cultures are positive for bacteria in 50%-75% of cases, bacterial proliferation may be a result of cholecystitis and not the precipitating factor for it.

Acalculous cholecystitis is related to conditions associated with biliary stasis, including debilitation, major surgery, severe trauma, sepsis, long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and prolonged fasting. Other causes of acalculous cholecystitis include cardiac events; sickle cell disease; Salmonella infections; diabetes mellitus; and cytomegalovirus, cryptosporidiosis, or microsporidiosis infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). (See Etiology.) For more information, see the Medscape Drugs & Diseases article Acalculous Cholecystopathy.

Uncomplicated cholecystitis has an excellent prognosis, with a very low mortality rate. Once complications such as perforation/gangrene develop, the prognosis becomes less favorable. Some 25%-30% of patients either develop some type of complication or require emergency surgery. (See Prognosis.)

The most common presenting symptom of acute cholecystitis is upper abdominal pain. The physical examination may reveal fever, tachycardia, and tenderness in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric region, often with guarding or rebound. However, the absence of physical findings does not rule out the diagnosis of cholecystitis. (See Presentation.)

Delays in making the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis result in a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality. This is especially true for intensive care unit (ICU) patients who develop acalculous cholecystitis. The diagnosis should be considered and the patient evaluated promptly to prevent poor outcomes. (See Diagnosis.)

Initial treatment of acute cholecystitis includes bowel rest, intravenous hydration, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, analgesia, and intravenous antibiotics. For mild cases of acute cholecystitis, antibiotic therapy with a single broad-spectrum antibiotic is adequate. Outpatient treatment may be appropriate for uncomplicated cholecystitis. If surgical treatment is indicated, laparoscopic cholecystectomy represents the standard of care. (See Treatment.)

Patients diagnosed with cholecystitis must be educated regarding causes of their disease, complications if left untreated, and medical/surgical options to treat cholecystitis. For patient education information, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Gallstones and Pancreatitis.

For further clinical information, see the Medscape Drugs & Diseases topic Acute Cholecystitis and Biliary Colic.

Pathophysiology

Ninety percent of cases of cholecystitis involve stones in the gallbladder (ie, calculous cholecystitis), with the other 10% of cases representing acalculous cholecystitis. [2]

Acute calculous cholecystitis is caused by an obstruction of the cystic duct, leading to distention of the gallbladder. As the gallbladder becomes distended, blood flow and lymphatic drainage are compromised, leading to mucosal ischemia and necrosis.

Although the exact mechanism of acalculous cholecystitis is unclear, several theories exist. Injury may be the result of retained concentrated bile, an extremely noxious substance. In the presence of prolonged fasting, the gallbladder does not receive a cholecystokinin (CCK) stimulus to empty; thus, the concentrated bile remains stagnant in the lumen. [3, 4]

A study by Cullen et al demonstrated the ability of endotoxins to cause necrosis, hemorrhage, areas of fibrin deposition, and extensive mucosal loss, consistent with an acute ischemic insult. [5] Endotoxins also abolish the contractile response to CCK, leading to gallbladder stasis.

Etiology

Risk factors for calculous cholecystitis mirror those for cholelithiasis and include the following:

-

Increasing age

-

Female sex

-

Pregnancy

-

Certain ethnic groups (eg, Native American Indians)

-

Obesity or rapid weight loss

-

Drugs (especially hormonal therapy in women)

Acalculous cholecystitis is related to conditions associated with biliary stasis, and include the following:

-

Critical illness

-

Major surgery or severe trauma/burns

-

Sepsis

-

Long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

-

Prolonged fasting

Other causes of acalculous cholecystitis include the following:

-

Cardiac events, including myocardial infarction

-

Sickle cell disease

-

Salmonella infections

-

Diabetes mellitus [6]

-

Patients with AIDS who have cytomegalovirus, cryptosporidiosis, or microsporidiosis

Patients who are immunocompromised are at an increased risk of developing cholecystitis from a number of different infectious sources. Idiopathic cases also exist.

Epidemiology

An estimated 10%-20% of Americans have gallstones, and as many as one third of these people develop acute cholecystitis. Cholecystectomy for either recurrent biliary colic or acute cholecystitis is the most common major surgical procedure performed by general surgeons, resulting in approximately 500,000 operations annually.

Age distribution for cholecystitis

The incidence of cholecystitis increases with age. The physiologic explanation for the increasing incidence of gallstone disease in the elderly population is unclear. The increased incidence in elderly men has been linked to age-related changes in the androgen-to-estrogen ratios.

See Pediatric Cholecystitis for more complete information on this topic.

Sex distribution for cholecystitis

Gallstones are 2-3 times more frequent in females than in males, resulting in a higher incidence of calculous cholecystitis in females. Elevated progesterone levels during pregnancy may cause biliary stasis, resulting in higher rates of gallbladder disease in pregnant females. Acalculous cholecystitis, however, is observed more often in elderly men.

Prevalence of cholecystitis by race and ethnicity

Cholelithiasis, the major risk factor for cholecystitis, has an increased prevalence in people of Scandinavian descent, Pima Indians, and Hispanic populations, whereas cholelithiasis is less common among individuals from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. [7, 8] In the United States, white people have a higher prevalence than black people.

Prognosis

Uncomplicated cholecystitis has an excellent prognosis, with a very low mortality. Most patients with acute cholecystitis have a complete remission within 1-4 days. However, 25%-30% of patients either develop some type of complication or require emergency surgery.

Once complications such as perforation/gangrene develop, the prognosis becomes less favorable. Perforation occurs in 10%-15% of cases. Patients with acalculous cholecystitis have a mortality ranging from 10%-50%, which far exceeds the expected 4% mortality observed in patients with calculous cholecystitis. In patients who are critically ill with acalculous cholecystitis and perforation or gangrene, mortality can be as high as 50%-60%.

The severity of acute cholecystitis also has an impact on the risk of iatrogenic bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. [9] Tornqvist et al reported a doubling of the risk for sustaining biliary damage in patients with ongoing acute cholecystitis compared to those without acute cholecystitis. Patients with Tokyo grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis and those with Tokyo grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis had, respectively, over double and more than eight times the risk of bile duct injury compared to those without acute cholecystitis. The risk of biliary injury was reduced by 52% with the intention to use intraoperative cholangiography. [9]

Complications

Bacterial proliferation within the obstructed gallbladder results in empyema of the organ. Patients with empyema may have a toxic reaction and may have more marked fever and leukocytosis. [10, 11] The presence of empyema frequently requires conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy. [12]

In rare instances, a large gallstone may erode through the gallbladder wall into an adjacent viscus, usually the duodenum, resulting in a fistula. Subsequently, the stone may become impacted in the terminal ileum or, less frequently, in the duodenal bulb and/or pylorus, causing gallstone ileus. [13]

Emphysematous cholecystitis occurs in approximately 1% of cases and is noted by the presence of gas in the gallbladder wall from the invasion of gas-producing organisms such as Escherichia coli, Clostridia perfringens, and Klebsiella species. This complication has a male predominance, is more common in patients with diabetes, and is acalculous in 28% of cases. Because of a high incidence of gangrene and perforation, emergency cholecystectomy is recommended. Perforation occurs in up to 15% of patients. [11, 14] For more information, see the Medscape Drugs & Diseases article Emphysematous Cholecystitis.

Other complications include sepsis and pancreatitis. [15]

-

Acute Cholecystitis. Normal finding on hepatoiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan.

-

Acute Cholecystitis. Abnormal finding on hepatoiminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan.