Background

Bile duct stricture (also called biliary stricture) is an uncommon but challenging clinical condition that requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgical specialists. Unfortunately, most benign bile duct strictures are iatrogenic, resulting from operative trauma [1] (see image below). Bile duct strictures may be asymptomatic but, if ignored, can cause life-threatening complications, such as ascending cholangitis, [2, 3] liver abscess, and secondary biliary cirrhosis.

However, not all bile duct strictures are benign. Pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma is the most common cause of malignant biliary strictures [4, 5, 6, 7] (see image below). Most of these patients die of complications of tumor invasion and metastasis rather than from the bile duct stricture per se. Nonetheless, both benign and malignant bile duct strictures can be associated with distressing symptoms and excessive morbidity. [8]

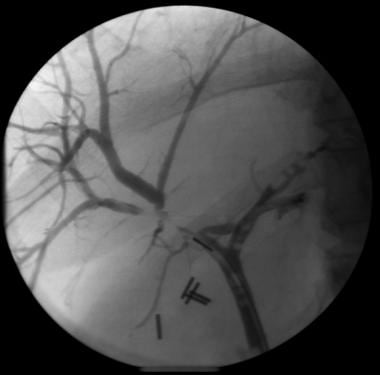

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram demonstrating an isolated mid-hepatic duct stricture as a result of pancreatic cancer.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram demonstrating an isolated mid-hepatic duct stricture as a result of pancreatic cancer.

For patient education resources, see Digestive Disorders Center and Infections Center, as well as Cirrhosis and Gallstones.

Pathophysiology

Strictures of the bile duct can be benign or malignant. Benign strictures develop when the bile ducts are injured in some way. The injury may be a single acute event, such as damage to the bile ducts during surgery or trauma to the abdomen; a recurring condition, such as pancreatitis or bile duct stones; or a chronic disease, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). After the injury, an inflammatory response ensues, which is followed by collagen deposition, fibrosis, and narrowing of the bile duct lumen.

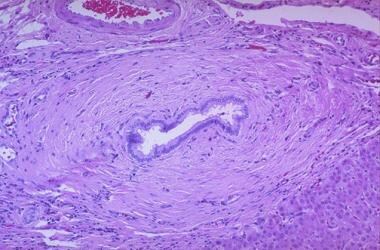

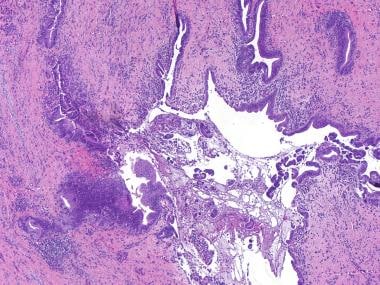

Periductal lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate that is consistent with autoimmune cholangiopathy.

Periductal lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate that is consistent with autoimmune cholangiopathy.

Depending on the nature of the insult, bile duct strictures can be single or multiple. Atrophy of the hepatic segment or lobe drained by the involved bile ducts, associated with hypertrophy of the unaffected segments, can occur, especially with chronic high-grade strictures. These changes can eventually progress to secondary biliary cirrhosis and the development of portal hypertension.

Malignant strictures are usually the result of either a primary bile duct cancer (ie, causing a narrowing of the bile duct lumen and obstructing the flow of bile) or extrinsic compression of the bile ducts by a neoplasm in an adjacent organ, such as the gallbladder, pancreas, or liver (see image below).

Etiology

Bile duct strictures can be benign or malignant.

Benign biliary strictures

Benign bile duct strictures causes include the following:

-

Postoperative injury after cholecystectomy: Approximately 80% of benign strictures occur following injury during a cholecystectomy. Injury to bile ducts can occur during either laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy. Most strictures after a laparoscopic procedure are short and occur more commonly in the common hepatic duct (ie, distal to the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts).

-

After open cholecystectomy, strictures are more common in the CBD. This phenomenon is likely due to the ease with which this area may be accessed by the laparoscope. Most iatrogenic injuries go unrecognized at the time of operation. Because of sepsis or peritonitis, the clinical status of the patient with an unrecognized biliary tract injury can deteriorate rapidly, thus early diagnosis is imperative.

-

The causes of benign bile duct strictures are usually surgical inexperience, failure to recognize abnormal biliary anatomy and congenital anomalies, acute inflammation, misplacement of clips, excessive use of cautery, and excessive dissection around the major bile ducts, resulting in ischemic injury. However, a significant proportion of strictures occur during operations described as simple and uneventful. Bile duct strictures can also occur as unexpected complications after other surgeries, such as gastrectomy, pancreatic surgery, or hepatic and portal vein surgery.

-

Pancreatitis: Jaundice due to an obstruction of the intrapancreatic segment of the CBD occurs in patients with chronic pancreatitis and accounts for approximately 10% of the benign strictures. Acute pancreatitis, pseudocyst, and pancreatic abscess are also uncommonly associated with the development of bile duct strictures.

-

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): PSC is a disease that causes strictures, beading, and irregularities of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Approximately 70% of PSC cases are associated with inflammatory bowel disease. The extent and distribution of bile duct involvement is variable.

-

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cholangiopathy: Patients with HIV cholangiopathy usually have advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) with CD4 lymphocyte counts less than 100/mm3 and poor long-term survival prognoses. Cryptosporidium and cytomegalovirus may be responsible for more than 90% of cases. Other causes of HIV cholangiopathy, occurring in fewer than 10% of patients, include microsporidia, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI), Cyclospora, Isospora, and Cryptococcus. Most patients present with severe right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever.

-

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) [9, 10, 11, 12, 13] : Bile duct strictures usually occur 2-6 months after OLT. Anastomotic strictures are more common, with choledochocholedochostomy site strictures being more common than choledochojejunostomy site strictures. Hepatic artery ischemia after OLT also can present as an anastomotic stricture, a hilar stricture, or diffuse stricturing of the biliary tree. Other causes of strictures after OLT are ABO incompatibility, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and chronic allograft rejection.

-

A study by Sundaram et al investigated the relationship between biliary strictures and transplantation in the era of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD). [14] The study concluded that even when using multivariate analysis to allow for other risk factors, transplantation in the post-MELD era is an independent predictor for stricture development. Further studies are needed to determine the etiology of this increase.

-

Mirizzi syndrome: This condition is observed in 1% of patients with cholecystectomies. Extrinsic compression of the common hepatic duct due to a gallstone impacted in the Hartmann pouch or cystic duct results in jaundice and cholangitis. Repeated episodes of inflammation can lead to formation of a stricture (type I) or pressure necrosis leading to the formation of a cholecystocholedochal fistula (type II).

-

Blunt abdominal trauma: This can lead to bile duct strictures, which usually have a delayed presentation.

-

Polyarteritis nodosa and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): These are autoimmune diseases involving small- to medium-sized arteries. They can present (rarely) as extrahepatic biliary obstruction secondary to biliary strictures.

-

Tuberculosis [17] and histoplasmosis: These conditions have rarely been reported to cause bile duct strictures in individuals who are immunocompetent.

-

Chemotherapeutic drugs: Hepatic artery infusion of 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FdUrd, FUDR) or other chemotherapeutic drugs may cause bile duct strictures.

-

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or papillary stenosis: Patients usually present with biliary colic after cholecystectomy. The anomaly is in the smooth muscle surrounding the terminal portion of the CBD, with an abnormal basal sphincter pressure of greater than 40 mm Hg.

-

Choledochal cysts: Choledochal cysts are uncommon anomalies of the biliary system manifested by cystic dilatation of the extrahepatic biliary tree, intrahepatic biliary tree, or both. This condition is found most frequently in Asian persons and in females. Associated hepatobiliary complications include recurrent cholangitis, bile duct stricture, cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, and recurrent acute pancreatitis.

-

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: This condition (previously known as Oriental cholangiohepatitis) and hepatolithiasis are prevalent in Southeast Asia and present a difficult management problem. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is characterized by recurrent attacks of suppurative cholangitis with strictures and dilatation of bile ducts and numerous pigment stones in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. It is thought to be precipitated by an infestation of liver flukes and round worms. In the United States, this disease is observed mostly in Asian immigrants.

-

Inflammatory strictures: In addition to pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis can also cause chronic inflammation and fibrosis, leading to strictures of the CBD and sphincter of Oddi.

-

Endoscope-related strictures: Postendoscopic sphincterotomy stricture is possible.

-

Idiopathic: A few cases of idiopathic benign bile duct strictures have been reported.

-

Miscellaneous: Strictures have been described in association with duodenal diverticulum, Crohn disease, hepatic artery aneurysm, cystic fibrosis with liver involvement, eosinophilic cholecystitis, and cholangitis.

Malignant biliary strictures

Malignant causes of bile duct strictures include the following:

-

Pancreatic cancer: In the United States, adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is the most common cause of malignant biliary obstruction. Pancreatic cancer accounts for nearly 33,000 cases of cancer each year and has become the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality. Pancreatic cancer usually presents in the sixth and subsequent decades of life.

-

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma: This pancreatic tumor may invade the bile duct and cause obstruction, which characteristically results in extrusion of mucin from the lumen.

-

Ampullary carcinoma: Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater usually arises from a benign adenoma. This condition is less common than pancreatic cancer, but symptoms of obstructive jaundice (80%) or pancreatitis are observed relatively early in its course. Both benign and malignant ampullary tumors can occur sporadically, or in the setting of genetic syndromes. The incidence of ampullary tumors is increased 200-300 fold in patients with hereditary polyposis syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

-

Gallbladder carcinoma: Extension of the cancer beyond the gallbladder can cause long bile duct strictures and obstruction, and it is a poor prognostic sign. In the United States, gallbladder cancer is the fifth most common gastrointestinal malignancy, with 6000 new cases each year. Gallbladder cancer occurs at a higher frequency in Native Americans and in people from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

-

Cholangiocarcinoma: This cancer arises from the biliary epithelium and is usually seen in association with choledochal cysts, PSC, chronic ulcerative colitis, and infestation by liver flukes. Obstructive jaundice is the major clinical manifestation of cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is more common in the upper portions of the biliary tree (hilar or Klatskin tumor) than in the lower portions of the biliary tree (distal bile duct cancer), but it can also be diffuse in 10% of cases (see image below).

-

For unclear reasons, the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has been rising over the past 2 decades in Europe, North America, Asia, Japan, and Australia, whereas rates of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are declining internationally.

-

Hepatocellular cancer: This is the most common primary liver malignancy. Hepatocellular cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the world and the third most common among men. Hepatocellular cancer is more common in the Far East than in the United States and is usually associated with cirrhosis resulting from hepatitis B or hepatitis C. The condition can present (rarely) with features of invasion of the extrahepatic biliary system as the predominant clinical manifestation.

-

Lymphoma and metastatic cancers to the liver and nodes in the porta hepatis: These cancers can sometimes be the cause of malignant bile duct strictures. Colorectal carcinoma, adenocarcinoma of the lung, pancreatic carcinoma, and renal cell carcinoma are the common tumors that metastasize to the liver. Metastatic porta lymphadenopathy may cause high-grade obstruction of the common hepatic duct.

Epidemiology

United States data

Although quite uncommon, the exact prevalence of bile duct strictures is unknown. One major category of bile duct strictures is postoperative bile duct stricture, which usually occurs as a result of a technical mishap during cholecystectomy, causing bile duct injury. Data from many large series of patients in the United States have revealed that the incidence rate of major bile duct injury is 0.2-0.3% after open cholecystectomy and 0.4-0.6% after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

International data

Data from Europe have shown a similar rate as that in the United States of occurrence of postoperative bile duct strictures.

Sex-related demographics

Data on the overall sex ratio of bile duct strictures are lacking. Some conditions causing bile duct strictures, such as PSC and chronic pancreatitis, are more common in men. The incidence of postcholecystectomy strictures is comparable in men and women.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with benign bile duct strictures is good. Patients who develop symptoms of biliary obstruction do well after surgical or endoscopic therapy.

Conversely, patients with HIV cholangiopathy or malignant biliary obstruction usually present at a late stage with widespread disease, and they generally have a dismal prognosis.

Morbidity/mortality

Bile duct strictures, independent of etiology, can cause significant morbidity from recurrent obstructive jaundice, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, biliary stones, and recurrent episodes of ascending cholangitis (see image below).

The major determinant of mortality in patients with bile duct strictures is the underlying disease condition. Patients with biliary strictures due to operative injury, radiation, trauma, or chronic pancreatitis generally have a good prognosis. Conversely, patients with bile duct strictures due to PSC and malignancy have a less favorable outcome.

Complications

Complications of bile duct strictures include development of stones in the gallbladder and bile ducts proximal to the stricture, pyogenic liver abscess due to recurrent episodes of ascending cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, and weight loss and malnutrition from steatorrhea, with fat-soluble vitamin deficiency.

Patient Education

Patients with biliary stents should be educated regarding how to recognize the symptoms of biliary obstruction and cholangitis that indicate blocked stents. Those with external drains should be taught how to flush their catheters until the catheters are internalized.

Patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis may benefit from counseling and alcohol abuse rehabilitation.

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic image of a cholangiocarcinoma at the bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts (Klatskin tumor).

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram demonstrating a long bile duct stricture that represents external compression by gallbladder cancer.

-

Transhepatic cholangiogram with an external drainage catheter in place.

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic image of a cholangiogram in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma whose condition has been treated with a metal stent.

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram of a solitary benign stricture of the distal bile duct. Resection demonstrated sclerosing cholangitis.

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram demonstrating an isolated mid-hepatic duct stricture as a result of pancreatic cancer.

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic cholangiogram demonstrating diffuse stricturing of the intrahepatic ducts that is consistent with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

-

Periductal onion skin fibrosis seen in primary sclerosing cholangitis.

-

Periductal lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate that is consistent with autoimmune cholangiopathy.

-

Focal intrahepatic benign bile duct stricture after cholecystectomy.

-

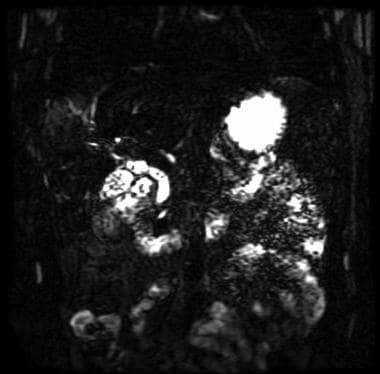

Multiple small bile duct stones seen on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

-

Irregular common bile duct stricture as a result of cholangiocarcinoma.

-

This image is an example of an intraoperative cholangiogram performed during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

-

Focal bile duct stricture as a result of pancreatic cancer in the head of the pancreas.

-

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram with balloon dilation of a postoperative bile duct stricture.

-

Benign distal common bile duct stricture seen during a cholecystostomy injection in an elderly male. The stricture resolved with a 4-week course of oral corticosteroid therapy.