Practice Essentials

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of normal endometrial mucosa (glands and stroma) abnormally implanted in locations other than the uterine cavity (see the image below). Approximately 30-40% of women with endometriosis will be subfertile.

Signs and symptoms

About one third of women with endometriosis remain asymptomatic. [1] When they do occur, symptoms, such as the following, typically reflect the area of involvement:

-

Dysmenorrhea

-

Heavy or irregular bleeding

-

Pelvic pain

-

Lower abdominal or back pain [2]

-

Dyspareunia

-

Dyschezia (pain on defecation) - Often with cycles of diarrhea and constipation

-

Bloating, nausea, and vomiting

-

Inguinal pain

-

Pain on micturition and/or urinary frequency

-

Pain during exercise

Patients with endometriosis do not frequently have any physical examination findings beyond tenderness related to the site of involvement. [3, 4, 5] The most common finding is nonspecific pelvic tenderness.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is considered the primary diagnostic modality for endometriosis. This is an invasive procedure with an overall sensitivity of 97% but with a specificity of only 77%.

The following sites are, in descending order, the most common sites of involvement found during laparoscopy:

-

Ovaries

-

Posterior cul-de-sac

-

Broad ligament

-

Uterosacral ligament

-

Rectosigmoid colon

-

Bladder

-

Distal ureter

Histology

Histologic demonstration of a combination of endometrial glands and stroma in biopsy specimens obtained from outside the uterine cavity is required to make the diagnosis of endometriosis.

Laboratory studies

-

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential - May help to differentiate pelvic infection from endometriosis, as well as to assess the degree of blood loss

-

Urinalysis and urine culture - If urinary tract infection (UTI) is in the differential diagnosis

-

Cervical Gram stain and cultures - Because sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) can also cause pelvic pain and infertility

Imaging studies

-

Ultrasonography - Endometriosis can be assessed by either transvaginal ultrasonography or endorectal ultrasonography

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The dependence of endometriosis on the cyclic production of menstrual cycle hormones provides the basis for medical therapy. Thus, the following drugs form the mainstay of pharmacologic care:

-

Combination oral contraceptive pills (COCPs)

-

Danazol

-

Progestational agents

-

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues

Surgical care for endometriosis can be broadly classified as follows:

-

Conservative - When reproductive potential is retained

-

Semiconservative - When reproductive ability is eliminated but ovarian function is retained

-

Radical - When the uterus and ovaries are removed

Conservative surgery

Conservative procedures used in the treatment of endometriosis include the following:

-

Drainage and laparoscopic cystectomy - Both procedures can be used in the treatment of ovarian endometriosis

-

Ablation

-

Presacral neurectomy

-

Laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA)

Semiconservative surgery

Semiconservative surgery is indicated mainly for women who have completed childbearing, are too young to undergo surgical menopause, and are debilitated by the symptoms. Such surgery involves hysterectomy and cytoreduction of pelvic endometriosis.

Ovarian endometriosis can be removed surgically, because one tenth of functioning ovarian tissue is all that is needed for hormone production. (Patients who undergo hysterectomy with ovarian conservation have a 6-fold higher rate of recurrence compared to women who undergo oophorectomy. [6] )

Radical surgery

Radical surgery involves total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy (TAH-BSO) and cytoreduction of visible endometriosis. Adhesiolysis is performed to restore mobility and normal intrapelvic organ relationships.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of normal endometrial mucosa (glands and stroma) abnormally implanted in locations other than the uterine cavity. This tissue, possessing the same steroid receptors as normal endometrium, is capable of responding to the normal cyclic hormonal milieu. Microscopic internal bleeding, with the subsequent inflammatory response, neovascularization, and fibrosis formation, is responsible for the clinical consequences of this disease. [7]

This condition is a common, poorly understood, and extremely debilitating benign gynecologic condition. The psychologic impact of the severe pain experienced by the patient is compounded by the negative impact of the disease on fertility. [2]

In the typical patient, the ectopic implants are located in the pelvis (ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, cervix, or uterosacral ligaments or in the rectovaginal septum) and manifest as severe dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, or infertility. More unusual implantation sites (laparotomy scars, pleura, lung, diaphragm, kidney, spleen, gallbladder, nasal mucosa, spinal canal, stomach, breast [8, 9] ) can be responsible for bizarre symptoms such as cyclic hemoptysis and catamenial seizures.

The etiology and pathophysiology of endometriosis is not well understood because of the lack of a suitable animal model on which to study the anatomic correlates and natural history of disease. [10] No cure exists for the disease, although the hormonal responsiveness of the implants can be exploited and provides the rationale for current methods of medical therapy. Treatment is directed toward medical suppression, surgical excision, and symptom alleviation.

Adenomyosis is the invasion of the myometrium by endometrial tissue.

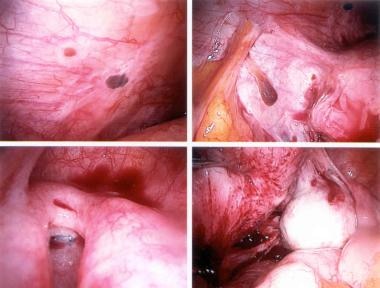

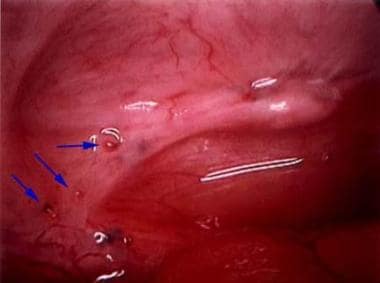

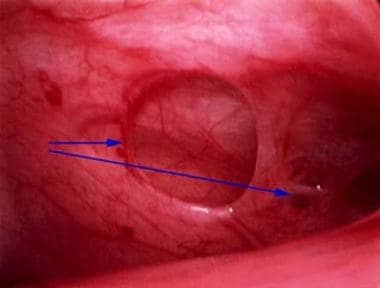

The following are some images of active endometriosis and old scarring.

See also Emergent Treatment of Endometriosis and Endometrial Ablation.

Pathophysiology

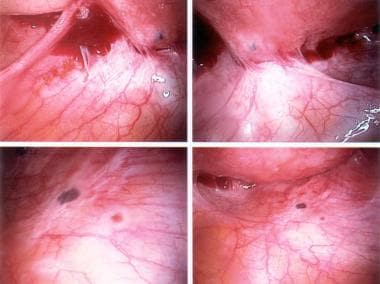

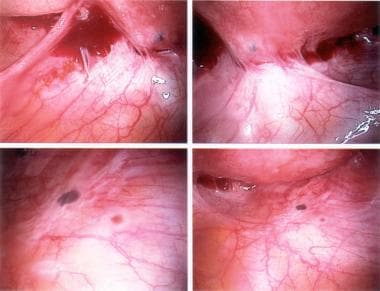

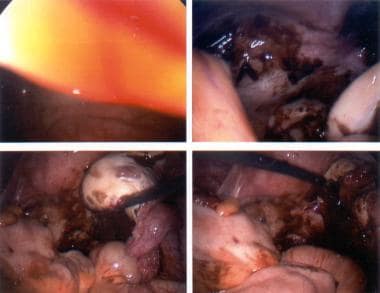

Ectopic endometrial tissues are most commonly located in the dependent portions of the female pelvis (eg, posterior and anterior cul-de-sac, uterosacral ligaments, tubes, ovaries), but any organ system is potentially at risk (see the following images).

Typical appearance of minimal endometriosis on the uterosacral ligaments. Note that some are pigmented (contain hemosiderin), whereas others are not.

Typical appearance of minimal endometriosis on the uterosacral ligaments. Note that some are pigmented (contain hemosiderin), whereas others are not.

Peritoneal erosions and adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac. These are typical of more severe endometriosis.

Peritoneal erosions and adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac. These are typical of more severe endometriosis.

These ectopic foci respond to cyclic hormonal fluctuations in much the same way as intrauterine endometrium, with proliferation, secretory activity, and cyclic sloughing of menstrual material. The products of this metabolic activity, including the concentrated and cyclic release of cytokines and prostaglandins, lead to an altered inflammatory response characterized by neovascularization and fibrosis formation. Some investigators have been able to demonstrate abnormal T- and B-cell function, abnormal complement deposition, and altered interleukin (IL)-6 production in women with this disease.

The associated pain, adhesion formation (see the image below), and anatomic distortion are responsible for the clinical consequences of this disease.

Etiology

The exact cause and pathogenesis of endometriosis is unclear. Several theories exist that attempt to explain this disease, although none have been entirely proven. [1] Leading theories include metaplastic conversion of coelomic epithelium and hematogenous or lymphatic dispersion of endometrial cells. It is likely a combination of various factors that cause and determine the severity of this disease.

Previous theories suggest that endometriosis results from the transport of viable endometrial cells through retrograde menstruation. Cells flow backward through the fallopian tubes and deposit on the pelvic organs, where they seed and grow. A population of cells resides in the endometrium, which retain stem cell properties. It may be these properties that allow these cells to survive in ectopic locations.

Risk factors for endometriosis include the following:

-

Family history of endometriosis

-

Early age of menarche

-

Short menstrual cycles (< 27 d)

-

Long duration of menstrual flow (>7 d)

-

Heavy bleeding during menses

-

Inverse relationship to parity

-

Delayed childbearing

-

Defects in the uterus or fallopian tubes

-

Hypoxia and iron deficiency may contribute to the early onset of endometriosis

Retrograde menstruation

Early in the 20th century (1927), Samson proposed his theory of retrograde menstruation through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity as a cause of endometriosis. Subsequent studies have shown that retrograde menstruation is a quite common physiologic event and cannot adequately explain the extrauterine implantation of endometrial tissue. Diagnostic laparoscopy during the perimenstrual period has shown that as many as 90% of women with patent fallopian tubes have bloody peritoneal fluid. Nonetheless, conditions that increase the rate of retrograde menstruation, such as congenital outflow tract obstructions, do increase the risk of endometriosis. Various animal experiments and clinical observations support this theory. [11, 12, 13, 14]

Because most women do not have endometriosis, perhaps immunologic or hormonal dysfunction leaves some women predisposed.

Immunologic dysfunction

Relatively recent research has suggested involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. An altered immune response to the displaced endometrial tissue has been shown to play an important role as well. Women with this disorder appear to exhibit increased humoral immune responsiveness and macrophage activation while showing diminished cell-mediated immunity with decreased T-cell and natural killer cell responsiveness. Humoral antibodies to endometrial tissue have also been found in sera of women with endometriosis. [15]

Intriguing nonhuman primate studies have demonstrated a strong association between dioxane exposure and the development of endometriosis, implying further that dysfunction of the immune system may contribute to this disease. However, epidemiologic investigations have not been able to confirm this association in humans.

Studies in recent years have focused on assessing the differences between eutopic endometrium and endometriosis. In endometriosis, an aberrantly expressed factor SF-1 activates the expression of the enzyme aromatase, which converts C19 steroids to estrogens. Consequently, estrogen increases the synthesis of prostaglandin E2, which exerts a positive feedback effect, resulting in increased aromatase activity. Additionally, endometriotic tissue is deficient in the enzyme 17-beta hydroxy steroid dehydrogenase type 2, which converts E2 in eutopic endometrium to the less potent E1 under the direction of progestins.

One study found a higher number of endometriomas, more bilateral disease, and a higher incidence of significant pain in women with aromatase positive disease. [16] However, other studies have shown increased cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in the stromal cells [17] and aberrant aromatase expression [18] in eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis.

Although successful treatment has been described with the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole in women with severe postmenopausal endometriosis, [19] more recent studies have also shown it to be effective in cases of severe endometriosis in premenopausal women. [20, 21] Additional data are needed before recommending this as primary treatment.

Metaplasia

Metaplasia, or the changing from one normal type of tissue to another normal type of tissue, is another theory. The endometrium and the peritoneum are derivatives of the same coelomic wall epithelium. Transformation of coelomic epithelium into endometrial-type glands in response to as yet unknown stimuli could explain endometriosis in unusual sites. [22] Coelomic metaplasia is also believed to explain the occurrence of endometriosis in women who have undergone total hysterectomy and are not taking estrogen replacement. [23] Peritoneal mesothelium has been postulated to retain its embryologic ability to transform into reproductive tissue. Such transformation may occur spontaneously, or it may be facilitated by exposure to chronic irritation by retrograde menstrual fluid.

Endometriosis may also occur in men on high-dose estrogen therapy. [24]

Remnant Mullerian cells

Another theory states that remnant Mullerian cells may remain in the pelvic tissues during development of the Mullerian system. Under situations of estrogen stimulation, they may be induced to differentiate into functioning endometrial glands and stroma.

Genetics

Some women may have a genetic predisposition to endometriosis. Studies have shown that first-degree relatives of women with this disease are more likely to develop it as well. The search for an endometriosis gene is currently under way.

Anatomic spread, dissemination and deposition

Transtubal dissemination is the most common route, although other routes, such as lymphatic and vascular channels, have been observed. This may explain how endometrial tissue can be found at distant, noncontiguous locations in the body.

Iatrogenic deposition of endometrial tissue has been found in some cases following gynecologic procedures and cesarean sections.

The ovary is the most common site for endometriosis. Spread to the ovary is believed to be lymphatic, [25] although superficial implants may be due to retrograde menstrual flow, because the ovaries are in a dependent part of the pelvis. Lesions can vary in size from spots to large endometriomas. The classic lesion is a chocolate cyst of the ovary that contains old blood that has undergone hemolysis (see the first image below). Once intracystic pressure rises, the cyst perforates, spilling its contents within the peritoneal cavity. This can cause the severe abdominal pain typically associated with endometriosis exacerbations. The inflammatory response causes adhesions that further increase the morbidity of the disease (see the second image below).

Uterine serosa can be affected. Vesicular lesions may provoke an inflammatory response and scarring that cause the bladder to adhere anteriorly. Posteriorly, the disease may cause obliteration of the cul-de-sac and form dense adhesions between the posterior vaginal wall or cervix and the anterior rectum. Severe dyspareunia, dyschezia, and alteration of bowel habits are the clinical sequelae of this common spread.

Deep peritoneal disease is caused by infiltration of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum by endometriotic nodules. Tethering of the uterus can lead to fixed retroversion. Dyspareunia is an important feature.

Through contiguous spreading, endometriosis may invade the rectovaginal septum and the anterior rectal wall. It may also involve the upper rectum and sigmoid colon, infiltrating the muscularis. Cyclical rectal bleeding (hematochezia) is pathognomonic of endometriosis. However, transmural bowel involvement by endometriosis remains a rarity. The ileum, appendix, and cecum may also be involved, leading to intestinal obstruction. Cicatrization as a consequence of endometriosis may lead to symptoms of obstruction even in postmenopausal women.

Although uncommon, interference in the genitourinary tract by endometriosis can affect the bladder, ureters, and kidneys by invasion, compression, or scarring. Medical therapy has less than satisfactory results, and surgical intervention is often required.

Uncommon sites include incisional scars, the umbilicus, and the thoracic cavity. Catamenial or cyclic pneumothorax can cause hemoptysis. Remember that ectopic endometrial tissue theoretically can undergo malignant transformation; histologic evaluation may be necessary. Significant predictive factors for the presence of malignant transformation of endometriosis appear to include age older than 49 years and cysts that are multilocular and have solid components. [26] Although elevated, levels of serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) do not appear to be a significant predictor of malignant transformation of endometriosis.

Postmenopausal endometriosis may be encountered in women who are on estrogen replacement therapy (ERT). Occasionally, if ERT is administered after total abdominal hysterectomy, endometriosis can be stimulated in an ovarian remnant. Extrapelvic endometriosis is believed to be hormone-resistant when it occurs after surgical castration. Transplantation of endometrial implants during the original surgery is believed to explain this occurrence. Another possible explanation is coelomic metaplasia.

Epidemiology

Endometriosis occurs in 6-10% of US women in the general population, [10] and approximately 4 per 1000 women are hospitalized with this condition each year. The exact incidence in the general population is unknown, because the definitive diagnosis requires biopsy or visualization of the endometriotic implants at laparoscopy or laparotomy. Most prevalence studies are based on a surgical population in which the likelihood of disease is greater, with the best estimates of incidence in the general female coming from women with proven fertility undergoing tubal sterilization procedures.

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease and, thus, usually affects reproductive-aged women. This condition has a prevalence rate of 20-50% in infertile women, [10, 27, 28, 29] but it can be as high as 71-87% in women with chronic pelvic pain. [10, 30] In a large series involving adolescent females with chronic pelvic pain, 45% were found to have endometriosis at laparoscopy. Of note, only 25% had a normal pelvis. In that series, the rate of endometriosis was found to increase with age from 12% in females aged 11-13 years to 45% in females aged 20-21 years. [31] In an earlier study, evidence of endometriosis was found during laparoscopy in 20-50% of asymptomatic women. [32]

A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a high prevalence of endometriosis among adolescent females with pelvic pain. Of 1011 symptomatic adolescents who underwent laparoscopic investigation, 648 (64%) were found to have endometriosis. [33, 34]

A familial association exists, with a 10-fold increased incidence in women with an affected first-degree relative. [35] Monozygotic twins are markedly concordant for endometriosis. [36]

Race-, sex-, and age-related differences in incidence

Most research and case studies have been performed in white populations; however, no difference appears to exist among ethnic or social groups. [37] Although endometriosis is obviously a disease largely confined to the female population, interestingly, scattered case reports exist of lesions that are histologically indistinguishable from endometriosis found in men exposed to high-dose exogenous estrogens.

Endometriosis is largely confined to women of reproductive age with an active hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Pelvic endometriosis typically occurs in women aged 25-30 years. Extrapelvic manifestations of this disorder occur in woman aged 35-40 years. Women younger than 20 years with this disease often have anomalies of the reproductive system. Prepubertal girls do not seem to be at risk for this disease, although the number of reports of endometriosis in young women shortly after menarche is increasing.

Menopause (whether spontaneous or induced through surgical or medical means) usually leads to resolution of symptoms. The disease seems to remain quiescent even in the face of hormone replacement therapy.

Prognosis

Endometriosis has been found to resolve spontaneously in one third of women who are not actively treated. [38] However, it is generally a progressive disease, with an unpredictable extent of progression and subsequent morbidity. Although most patients (up to 95% in some studies) respond to medical therapy (suppression of ovulation) for decreasing pelvic pain, such therapy is ineffective for treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility but does preserve the potential for conception. Nonetheless, as many as 50% of women have a return of symptoms within 5 years with medical management.

Combination estrogens/progestins relieve pain in as many as 80-85% of patients with endometriosis-related pelvic pain. After 6 months of danazol therapy, as many as 90% of patients with moderate endometriosis experience adequate pain relief.

Findings from the prospective Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health of 9,585 women (age at trial onset, 18-23 y) indicated that, regardless of fertility status, previous exposure to oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) reduced the risk of a subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis among parous women but increased the risk among nulliparous women. [39]

Relative to women who never used OCPs, the hazard ratio (HR) for endometriosis among women with up to 5 years of OCP use before diagnosis was 1.8 in nulliparous women compared with 0.41 in parous women. In those with a history of OCP use for 5 years or longer, the HR was 2.3 in nulliparous women and 0.45 in parous women. [39] The investigators suggested a possible reason for the twofold increased risk of endometriosis among the nulliparous women may have been early noncontraceptive use of OCPs.

Minimally invasive surgical therapy affords better fertility rates, but this treatment is not as effective at eliminating pain. Definitive surgical therapy (total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [TAH-BSO] and peritoneal stripping) offers the best chance for long-term resolution of pain (up to 90%). However, reserve this option as a last resort in patients with completely incapacitating disability or those who have no desire for future childbearing.

In general, pregnancy is possible but depends on the severity of the disease. Endometriosis signs and symptoms generally regress with the onset of menopause and during pregnancy.

Mortality/morbidity

Acute or chronic pelvic pain is common in patients with endometriosis. Infertility is also common. Approximately 30-40% of women with endometriosis will be subfertile.

Adolescent patients typically present with increasingly severe dysmenorrhea and/or chronic pelvic pain. Any persistent symptoms that seem cyclic in nature should prompt the practitioner to consider a search for endometriosis.

Symptoms do not correlate well with disease severity. Significant dysfunction can be present with minimal gross disease, whereas severe endometriosis is sometimes asymptomatic. The pain of endometriosis responds poorly to antiprostaglandins and OCPs. Symptoms are related to the site of endometriotic implants and the organ system involved.

Cases have been reported of extrapelvic involvement in virtually every other organ system including the central nervous system (CNS), lungs, pleura, kidney, and bladder. [8, 9] The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most common extrapelvic site of endometriosis, and symptoms include bowel obstruction, rectal bleeding, and constipation. Symptoms in other locations are related to the site and size of endometrial implants.

Mortality is negligible.

Complications

Complications of endometriosis may include or fall into the following 3 categories:

-

Infertility/subfertility

-

Chronic pelvic pain and subsequent disability

-

Anatomic disruption of involved organ systems (eg, adhesions, ruptured cysts)

Endometriosis has also been linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Farland et al found that pregnant women with a history of endometriosis were at increased risk for spontaneous abortion (relative risk [RR], 1.40; 95% CI, 1.31-1.49), ectopic pregnancy (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.19-1.80), gestational diabetes (RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.11-1.63), and hypertensive disorders (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.16-1.45). [40, 41]

Patient Education

Stress to patients the importance of continuing medical therapy for the full 6-month course. Medical therapy often relieves pain but induces uncomfortable adverse effects, and the patient needs encouragement to complete the course of treatment. Recurrence of symptoms after therapy should prompt the patient to return for further evaluation. Educate patients with severe disease about the symptoms of bowel and ureteral obstruction.

For patient education information, see Pregnancy Center and Women's Health Center, as well as Endometriosis, Female Sexual Problems, Birth Control Overview, and Birth Control Methods.

For patients interested in more information or support groups, Endometriosis Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), The Endometriosis Association, and Endometriosis.org are valuable resources.

-

Powder-burn lesions of endometriosis.

-

Endometriosis. Chocolate cyst of the ovary.

-

Endometriosis. Red lesions on the sigmoid colon and cul-de-sac.

-

Adhesions due to endometriosis.

-

Endometriosis. Red lesions on various organs.

-

Active endometriosis with red and powder-burn lesions and adhesions from old scarring.

-

Scarring due to old disease and active endometriosis.

-

Endometriosis. Moderate-to-severe disease.

-

Typical appearance of minimal endometriosis on the uterosacral ligaments. Note that some are pigmented (contain hemosiderin), whereas others are not.

-

Peritoneal erosions and adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac. These are typical of more severe endometriosis.