Practice Essentials

Nonbacterial prostatitis refers to a condition that affects patients who present with symptoms of prostatitis but without a positive result on culture of urine or expressed prostate secretions (EPS). [1] Bacterial causes and their presentations can be reviewed in Acute Bacterial Prostatitis and Prostatic Abscess, Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis, and Bacterial Prostatitis.

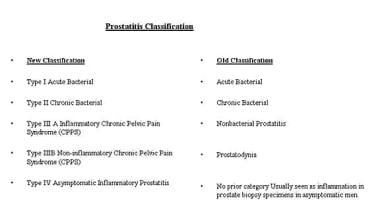

Prior to 1995, the diagnosis of prostatitis was based on the classification of Meares and Stamey, which classified prostatitis into the following four categories:

-

Acute bacterial prostatitis

-

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

-

Nonbacterial prostatitis

-

Prostatodynia.

In 1995, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) convened a workshop on prostatitis and developed a new classification scheme. [2, 3] The first two categories—acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis—remained the same. Nonbacterial prostatitis and prostatodynia were combined as category III (ie, chronic abacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome [CPPS]). Category III was further subdivided into IIIa, inflammatory CPPS, and IIIb, noninflammatory CPPS. Category IV encompasses asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis. See the image below for a comparison of the old and new categories of prostatitis.

Prostate specimens often reveal evidence of category IV prostatitis after a biopsy. However, patients with category IV prostatitis have no symptoms. Though not recommended, some physicians treat these patients with antibiotics in an effort to lower their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level. [4, 5]

The rationale for the new diagnostic classification was to promote additional research to find effective forms of treatment for a symptom complex that cannot always be attributed to a bacterial infection.

Traditional treatment of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (IIIa and IIIb) was with antibitotics for 4-6 weeks. However, a large percentage of patients do not show infection of their prostate secretions and the long-term use of quinolone antibiotics put these patients at increased risk of tendon rupture. Increasing rates of antibiotic resistance also make this approach less favorable. By dividing chronic prostatitis into two categories, IIIa (inflammatory) and IIIb (noninflammatory), the IIIa patients with inflammatory cells on expressed prostatic secretion can receive a short course of antibiotics (2 wk), while the IIIb patients without inflammatory cells can receive other, nonantimicroial therapy. [6]

Go to the overview topic Prostatitis for complete information on this subject.

Pathophysiology

Of all men evaluated for prostatitis, only 5-10% actually have a true bacteriologic condition as evidenced by a positive urine culture. However, approximately 50% of these men nevertheless receive antibiotics for treatment of the prostatitis symptom complex.

Evidence suggests that despite negative culture findings, some patients with nonbacterial prostatitis in the traditional sense may have a bacterial infection. Studies have found bacterial ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the prostatic fluid of patients with prostatitis symptoms.

In addition, some fastidious organisms that do not grow in standard culture media may be the cause of the symptom complex. Some of these organisms are Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Despite having nonbacterial prostatitis by the classic definition, these patients improve with an appropriate, short course of antibiotics.

The pathophysiology of chronic abacterial prostatitis has not been fully elucidated, emphasizing the lack of understanding of this disease complex. However, chronic abacterial prostatitis may involve an etiology similar to that of chronic bacterial prostatitis. The peripheral zone of the prostate is composed of a system of ducts, which possess a poor drainage system that prevents the dependent drainage of secretions. As the prostate enlarges with increasing age, patients develop obstructive symptoms and urine refluxes into the prostatic ducts.

Urine reflux may also occur in patients with urethral stricture disease, voiding dysfunction, or benign prostatic hyperplasia. Refluxing urine, even when it is sterile, may lead to chemical irritation and inflammation. Tubule fibrosis is initiated, and prostatic stones form and lead to intraductal obstruction and stagnation of intraductal secretions. This obstruction initiates an inflammatory response, and prostatitis symptoms develop.

A fastidious organism may cause an infection by ascending up the urethra or through reflux of infected urine into the prostatic ducts. Additionally, many men with prostatitis are also more prone to having allergies. Thus, these men may also have autoimmune-mediated inflammation caused by a preceding true infection.

Etiology

Nonbacterial prostatitis may be caused by fastidious organisms that cannot be cultured routinely from a urinary specimen. A negative result after routine urine culture is the reason the syndrome is referred to as nonbacterial prostatitis. These fastidious organisms include C trachomatis, U urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, N gonorrhoeae, viruses, fungi, and anaerobic bacteria. Noninfectious causes of prostatitis have not been definitively proven, but allergies and autoimmune diseases (eg, reactive arthritis), are hypothesized causes.

Other purported etiologies are bladder neck or urethral spasm, a male variant of interstitial cystitis, and pelvic floor tension myalgia. [7] See Interstitial Cystitis for more information.

Pelvic floor tension myalgia is also known as levator ani syndrome. This syndrome often is diagnosed based solely on symptoms of a vague dull ache in the rectal area that often worsens when sitting or lying down. Symptoms can last for hours or days. Pelvic floor tension myalgia may result from overly contracted pelvic floor muscles due to psychological stress, tension, and anxiety.

The prevalence rate is approximately 6.6% in the general population and is higher in women. It is observed in persons aged 30-60 years, but incidence decreases in those older than 45 years.

Carcinoma in situ of the bladder, which can present with irritative urinary symptoms, must be considered and excluded.

Epidemiology

Approximately half of all men develop symptoms consistent with prostatitis at some time in their lives. Prostatitis symptoms are very common in men aged 35-50 years. These symptoms are the most common urologic problem in men younger than 50 years and the third most common urologic problem in older men; these symptoms account for 25% of men evaluated for a urologic problem and 8% of all visits to urologists. [8, 9]

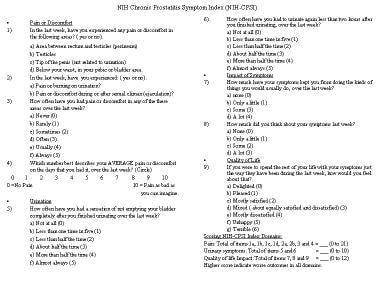

Studies using the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI; see image below) found the prevalence of prostatitis symptoms to be approximately 10% in a population of men aged 20-74 years. The most common form of prostatitis (90%) is category III, ie, chronic abacterial prostatitis and CPPS.

No racial predilection is found. The common age range for presentation of prostatitis symptoms is 36-74 years.

Patient Education

Patients should be instructed to try to limit stress in their lives, which may exacerbate symptoms. Some urologists, the author included, also recommend frequent ejaculation to prevent a buildup or stasis of secretions within the prostate, thus avoiding inflammation and prostatitis symptoms.

Patients should be told that certain foods (see Dietary Considerations) may cause more irritation; and, with a little experimenting, they can determine which foods to avoid or limit.

For patient education information, see Prostatitis.

-

Nonbacterial prostatitis. National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index.

-

Nonbacterial prostatitis. Comparison of new and old prostatitis classifications.

-

Treatment algorithm for nonbacterial prostatitis.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Antibiotics

- Alpha-Adrenergic Blocking Agents

- 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agents

- Benzodiazepines

- Interstitial Cystitis Agents

- Uricosurics

- Flower Pollens

- Muscle relaxants

- Anticholinergic agents

- Anticonvulsants, Other

- Tricyclic Antidepressants

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References