Overview

Most malignant cutaneous neoplasms that involve the male genitalia are squamous in origin and associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. [1, 2, 3] The overall prevalence of HPV DNA in penile carcinoma is approximately 40-45%. HPV type16 predominates and in one study represented 79% of all high-risk HPV infections. [4] In a biopsy cohort of 2754 men with external genital lesions, condyloma primarily contained HPV 6 or 11; penile intraepithelial neoplasia lesions primarily contained HPV 16, but one grade III lesion was positive for HPV 6 only. [5] Tobacco use has also been associated with penile cancer. [6]

Less commonly, tumors arise from cutaneous adnexa, melanocytes, soft tissue, or lymphoid tissue. Cutaneous metastases of the penis are rare and usually occur in the setting of widely disseminated metastatic disease.

Penile neoplasia of squamous origin includes both in situ and invasive carcinoma. In situ squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, also known as penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), encompasses 3 clinical variants: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and bowenoid papulosis. The distinction depends on the anatomic location and clinical presentation of the lesions. Erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease share histopathologic features and biologic behavior and are associated with similar HPV subtypes. The two diseases are considered to represent clinical variants of a single pathologic process.

The in situ carcinoma microscopic features of bowenoid papulosis are also similar, and the condition is also associated with HPV; however, it differs from erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease in clinical presentation and exhibits a significantly lower rate of malignant transformation.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is an uncommon tumor that usually develops in older uncircumcised men. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, as well as psychological trauma. The etiology of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis is less understood than in situ carcinoma. Although invasive squamous cell carcinoma is associated with HPV, other factors also appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of the tumors.

The clinical presentation of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis varies. Invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the penis are most commonly well-differentiated neoplasms that can present clinically as exophytic, verrucous, or flat lesions. The overall prognosis of penile squamous cell carcinoma is related to the extent of tumor invasion and regional lymph node status.

Nonsquamous malignant neoplasms of the penis are rare and include soft tissue sarcomas, melanomas, and lymphomas.

For patient education information, see the Men's Health Center and Penile Cancer Center.

Staging

Both the European Association of Urology and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend staging penile tumors using the 2016 UICC TNM classification. [7, 8, 9] With the publication of this addition, the T1 category was stratified into two prognostically different risk groups, depending on the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion and grading. [8]

The TNM classification of the primary tumor (T) is below. [8]

-

TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

-

T0: Primary tumor is not evident

-

Tis: CIS is present. (penile intraepithelial neoplasia [PIN])

-

Ta: Noninvasive verrucous carcinoma

-

T1: Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue; T1a, without lymphovascular invasion and not poorly differentiated; T1b, with lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated

-

T2: Tumor invades corpora spongiosum with or without invasion of the urethra

-

T3: Tumor invades the corpora cavernosum with or without invasion of the urethra

-

T4: Tumor invades other adjacent structures

Erythroplasia of Queyrat

Initially described by Tarnowsky in 1891, erythroplasia of Queyrat (see Erythroplasia of Queyrat [Bowen Disease of the Glans Penis]) was separated from Bowen disease on the basis of clinical appearance, anatomic location (inner lining of the foreskin and glans penis), and lack of an association with internal malignancy. The histopathologic features and rates of progression to squamous cell carcinoma are similar for both erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.

Because of the clinical and biologic overlap of the two diseases, they are thought to represent clinical variants of in situ squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. The reported association with internal malignancy may be more related to the older age of the patients and has been called into question for both erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.

Pathophysiology

Erythroplasia of Queyrat occurs almost exclusively in uncircumcised men and is reported in both young and older men. The lesion is an intraepithelial or in situ neoplasm; the associated risk for progression to invasive carcinoma has been documented as up to 33%. [10] The specific etiologic factors remain unclear. Predisposing factors include lack of circumcision, poor hygiene, and chronic infection.

Several HPV serotypes have been isolated from this disease, including HPV 8, 16, 18, 39, and 51. [11, 12] Circumcision has been proposed to protect against the development of erythroplasia of Queyrat, possibly secondary to facilitation of better hygiene, less accumulation of smegma, and reduced risk of chronic infections.

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

Erythroplasia of Queyrat presents as a bright red, well-demarcated, velvety plaque or plaques that involve the glans, coronal sulcus, or prepuce. [11] Lesions are often present for months to years before clinical attention is sought. Biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Ulceration may signal an invasive lesion. The histopathology is similar to that of bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease, showing features of in situ carcinoma such as full-thickness epithelial atypia with lack of maturation, nuclear atypia, dyskeratosis, and atypical mitoses. The underlying dermis typically displays a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Evidence of tumor invasion into the underlying dermis is absent. See the image below.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses include the following:

-

Zoon balanitis (see Balanitis Circumscripta Plasmacellularis)

-

Erosive lichen planus (see Cicatricial Pemphigoid)

-

Psoriasis (see Cutaneous Candidiasis)

-

Fixed drug eruption (see Psoriasis)

Pigmented Bowen disease can also mimic seborrheic keratosis, melanoma (see Malignant Melanoma), or melanocytic nevi.

Treatment

Treatment of erythroplasia of Queyrat involves removal or destruction of the lesion; however, no therapy is standard. Treatment methods used include topical therapy, cryotherapy, laser ablation, radiotherapy, diathermy, surgical excision (including partial penectomy), and Mohs micrographic surgery. [13, 14] The latter 2 surgical modalities have the advantage of allowing microscopic examination of the specimen to assess clear margins and ruling out the presence of invasive tumor. Mohs micrographic surgery offers the additional advantage of maximizing tissue preservation.

More recently, photodynamic therapy in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery has been used. [15, 16] Topical therapy with either 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or imiquimod has shown success in limited studies. [17]

Outcome

Up to 33% of lesions show progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. In a series of 100 cases, 22% of the patients developed recurrence, 8% developed invasive squamous cell carcinoma, and 2% developed squamous cell carcinoma with distant metastases. [18]

Bowen Disease

First described by Bowen in 1912, Bowen Disease was considered unique because of its association with invasive squamous cell carcinoma and internal visceral malignancy. Subsequently, the rate of progression to invasive carcinoma was shown to be similar to that of erythroplasia of Queyrat. A significant association with internal malignancy has not been demonstrated.

Pathophysiology

Bowen disease is a clinical presentation of in situ squamous cell carcinoma that involves the shaft of the penis. The pathogenesis is unclear; however, risk factors include exposure to ultraviolet light, chemical carcinogens, and arsenic. HPV types 16, 18, and 57b have been isolated from lesions of Bowen disease. [19] However, the specific role of HPV in the pathogenesis is debated.

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

Bowen disease is generally seen in elderly uncircumcised men and presents as a sharply marginated, erythematous, scaly patch or plaque on the shaft of the penis. A pigmented variant exists and has been reported in men with AIDS. The lesion can range from millimeters to centimeters in diameter. Ulceration may signal an invasive lesion.

Biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. The histopathology is similar to that of bowenoid papulosis and erythroplasia of Queyrat, showing features of in situ carcinoma, such as full-thickness epithelial atypia with lack of maturation, nuclear atypia, dyskeratosis, and atypical mitoses. The underlying dermis typically displays a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Evidence of tumor invasion into the underlying dermis is absent.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses include the following:

-

Paget disease

Pigmented Bowen disease can also mimic seborrheic keratosis, melanoma, or melanocytic nevi.

Treatment

Treatment of Bowen disease involves removal or destruction of the lesion; however, no therapy is standard. Treatment methods include topical therapy, cryotherapy, laser ablation, surgical excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. The latter two surgical modalities have the advantage of allowing microscopic examination of the specimen to assess clear margins and to rule out the presence of invasive tumor. Mohs micrographic surgery offers the additional advantage of maximizing tissue preservation. Topical therapy with either 5-FU or imiquimod has shown success in limited studies.

Outcome

The rate of progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma is 5-10%, similar to that observed in erythroplasia of Queyrat. Of the cases progressing to invasive carcinoma, 30-50% are potentially metastatic. Initial reports suggested that as many as 33% of patients with Bowen disease develop visceral malignancies including respiratory, gastrointestinal, or urogenital cancers. Subsequent studies have not demonstrated a paraneoplastic association. [20]

Bowenoid Papulosis

In 1970, Lloyd first described lesions of bowenoid papulosis. [21] Wade initially applied the term bowenoid papulosis in 1978 (see Bowenoid Papulosis) as a specific disorder seen predominantly in young, sexually active males. [22] Although the lesions show histopathologic features of in situ carcinoma similar to those of erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease, they exhibit a much lower rate of progression to invasive neoplasms.

Pathophysiology

Bowenoid papulosis generally develops in sexually active men aged 20-40 years. The mean age at presentation is 29.5 years. An association with HPV infection has been documented, and several HPV serotypes from lesions of bowenoid papulosis have been detected, including HPV 1, 6, 11, 16, 18, 31-35, 39, 42, 48, 51-54, and 67. HPV 16 is the most commonly detected serotype. [23] Although bowenoid papulosis can show progression to squamous cell carcinoma, the rate is < 1%. [24, 25, 26]

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

Patients typically present with solitary or multiple, rapidly growing, red-brown to violaceous, flat-topped papules that may coalesce into larger plaques on the penile shaft or the perineum. The papules are nonpruritic, range in size from 2-10 mm, and usually lack scale.

Biopsy is usually necessary for a definitive diagnosis. The histopathology is similar to that of erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease, showing features of in situ carcinoma, including full-thickness epithelial atypia with lack of maturation, nuclear atypia, dyskeratosis, and atypical mitoses. The underlying dermis typically displays a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Evidence of tumor invasion into the underlying dermis is absent. [27] Because of the histopathologic overlap with erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease, correlation with the clinical presentation is essential for diagnosis.

Differential diagnoses

Lesions may be clinically mistaken for condyloma acuminatum, seborrheic keratoses, or nevi. Differential diagnoses also include nonspecific balanitis, including Zoon balanitis (see Balanitis Circumscripta Plasmacellularis).

Treatment

Because of the characteristic benign course of the disease, conservative therapy is appropriate. Treatment centers on ablation of the gross lesion or lesions. Modalities include cryotherapy, laser ablation, and topical therapy with either 5-FU or imiquimod. Remission has been demonstrated in patients infected with HIV who are receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as well as healthy men. [28, 29, 30]

Outcome

The risk of progression from bowenoid papulosis to squamous cell carcinoma is < 1%. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk of developing invasive lesions. In some cases, bowenoid papulosis may regress spontaneously. Because of the association with HPV, this is considered a sexually transmitted disease. Studies of partners of patients with bowenoid papulosis found them to be at a higher risk for cervical dysplasia.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (see Squamous Cell Carcinoma) is the most common malignant primary tumor of the penis, accounting for 48-65% of all malignant penile neoplasms. [7] Although rare in persons younger than 40 years, the age at presentation ranges from 20-90 years. Most cases occur in elderly uncircumcised men and are associated with poor hygiene. In the United States, penile cancer accounts for less than 1% of all malignancies. Areas of high rates of penile squamous cell carcinoma include Uganda, Brazil, Jamaica, Mexico, India, and Haiti. Squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum also occurs but is less common than squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. [31]

Pathophysiology

The specific etiology and pathogenesis of penile squamous cell carcinoma is unclear. Initial reports showed that penile squamous cell carcinoma was associated with lack of circumcision. High rates of tumors were documented in uncircumcised Hindus and low rates among Jews who practice ritual circumcision. Later studies revealed a low rate of penile tumors among Scandinavians who do not practice circumcision and indicated that the crucial factor was not the foreskin itself, but the link between foreskin retention and poor hygiene.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis has been associated with phimosis; however, the presence of phimosis often indicates scarring from a previous infectious or inflammatory reaction. It is estimated that 31-66% of all penile cancers are HPV related, with type 16 virus being most common. [32] Subtypes linked to penile squamous cell carcinoma include high-risk types 16 and 18, as well as 6, 11, and 30. Penile cancer is also associated with spousal cervical cancer, although these statistics have been debated. The following have also been suggested as risk factors for the development of penile carcinoma:

-

Smegma retention

-

Chronic balanitis

-

Ultraviolet light exposure

-

Chemical carcinogen exposure

-

Cigarette smoking

-

HIV infection

-

Immunosuppression

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

Most lesions present on the glans, followed by the prepuce, coronal sulcus, and shaft. Tumors typically present as an ulcerated mass and can exhibit either a flat or an exophytic, papillary clinical growth pattern. Presenting symptoms often include penile pain, malignant priapism, discharge, and difficulty voiding. Lymphadenopathy is present in 28-64% of cases at presentation.

Biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. The histopathology shows features of invasive carcinoma and can exhibit morphologic heterogeneity. Most tumors are well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. Other variants include basaloid, sarcomatoid (or spindled), and verrucous growth patterns. The underlying dermis typically displays a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Angiolymphatic invasion may be present.

Patients are staged and tumors are graded according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging and modified Broders systems, respectively. The TNM system classifies cases into stages I-IV based on the extension of the tumor. Most patients present as stage I (confined to the glans) or II (involving the glans and invading into the penile shaft). Histologic grading using the modified Broders classification divides tumors into four histologic grades ranging from well differentiated to poorly differentiated.

Another grading system uses a three-tier (well, moderate, poor) scale for differentiation, with 50% of cases being well differentiated. Of note, well-differentiated tumors metastasize to regional lymph nodes at a rate of 50%, while moderate or poorly differentiated tumors have an 80-100% nodal metastasis rate. Hematogenous metastasis is uncommon, accounting for fewer than 2% of cases at diagnosis. See the images below.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This lesion is large but mainly shows broad superficial invasion upon sectioning. The white jagged line is the fibrotic response to the invading tumor.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This lesion is large but mainly shows broad superficial invasion upon sectioning. The white jagged line is the fibrotic response to the invading tumor.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This case obliterates the tip of the glans and distorts the prepuce. Note the large size, typical of these lesions at presentation.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This case obliterates the tip of the glans and distorts the prepuce. Note the large size, typical of these lesions at presentation.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prepuce: The ulcerating tumor is noted to arise from a background of inflamed prepuce.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prepuce: The ulcerating tumor is noted to arise from a background of inflamed prepuce.

Differential diagnoses

Given the anatomic location and clinical presentation, the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma is generally straightforward. The differential diagnoses include the following:

-

HPV infection

-

Atypical herpes simplex infection

-

Malignant cutaneous adnexal tumors

-

Sarcomas

-

Amelanotic melanoma

Treatment

The primary treatment for penile carcinoma is surgical and varies according to tumor type and stage of disease. Radiation, chemotherapy, or both are often used as adjunctive therapy, depending on the stage of disease.

Topical chemotherapy such as imiquimod or 5-fluoruracil (5-FU) is first line treatment in cases of carcinoma in situ. [33, 7, 9] Other options include laser ablation or total or partial glans resurfacing. [34, 35] European Association of Urology guidelines note that superficial lesions (Tis, Ta, and T1a disease) can be treated with the following penis-sparing techniques [7] :

-

Laser therapy (Tis, Ta, T1a)

-

Glans resurfacing (Tis, Ta, T1a)

-

Wide local excision with circumcision (Ta, T1a)

-

Glansectomy with reconstruction (Ta, T1a)

-

Radiotherapy for lesions < 4 cm (Ta, T1a)

Surgical intervention involves wide excision, partial penectomy, or total penectomy. To determine whether conservative surgery (glansectomy only) can be performed, European Association of Urology guidelines suggest that magnetic resonance imaging (in combination with an artificial erection from prostaglandin E1) may be used to help identify the depth of invasion of corpora. [7] Some groups have argued for local excision with conversion to partial penectomy upon recurrence, although this is not widely accepted.

More recently, an emphasis has been placed on organ-sparing surgery, in recognition of the significant impact that penectomy and partial penectomy may have on health-related quality of life, sexual function, and self-esteem. The literature shows that in properly selected patients with penile cancer, the oncologic outcomes of organ-sparing surgery are comparable to those of conventional treatment that includes penectomy and partial penectomy. [36]

Compared with partial penectomy, penis-sparing techniques are associated with a better quality of life. Local recurrence rates are generally higher with penis-sparing techniques than with partial penectomy (5-12% versus 5%), but with good salvage rates the impact on survival is minimal. [37] For tumors stage 2 or lower and less than 4 cm, radiotherapy is also a penis-sparing option. [38, 39] Total penectomy with perineal urethrostomy may be needed for higher-stage (T3-T4) or proximal tumors. [32]

The effectiveness of prophylactic bilateral inguinal node dissection is controversial. A study by Djajadiningrat et al of prophylactic pelvic lymph node dissection in 79 penile cancer patients without preoperative evidence of pelvic disease found that inguinal extranodal extension or two or more inguinal tumor-positive lymph nodes are predictive for pelvic tumor positivity. Patients with pelvic node involvement treated with surgery only had a poor prognosis, with 5-year disease-specific survival of 17%. [40]

Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been successfully used in the surgical management of penile carcinoma and can provide staging and prognostic information. [41]

The role of chemotherapy is unclear because of the difficulty in gathering a sizable number of patients. Commonly used agents include cisplatin and bleomycin and have yielded response rates of 15-23%. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with vinblastine, bleomycin, and methotrexate has been used in T1b and T4 disease. [40] Combination chemotherapy and radiation using bleomycin-derived treatments have been successful in some cases, with response rates as high as 43%.

Outcome

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis tends to be a locally advanced, aggressive disease. The prognosis correlates with the extent of tumor invasion and lymph nodes status. Survival is most closely related to lymph node status. According to a recent study, the 5-year survival rate is 93% for stage I, 55% for stage II, and 30% for stage III disease. Involvement of the pelvic lymph nodes is associated with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5%. Death typically occurs within 2 years if tumors are left untreated. Nodal metastases, usually to the inguinal and/or iliac nodes, are the most common route of dissemination. Of note, 5-15% develop second primary lesions, often located in the residua of the penis.

Complications are usually due to recurrence, which occurs in as many as 7% of patients. In addition to the extent of tumor invasion and lymph node status, histologic type plays a role in prognosis. Worse prognosis is associated with basaloid and sarcomatoid subtypes. Verrucous carcinoma (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor) is a well-differentiated, low-grade variant of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by local invasion and a low incidence of metastasis.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

While basal cell carcinomas (see Basal Cell Carcinoma) are the most common human malignant tumor, they are distinctly uncommon on the male genitalia. Most cases documented in the medical literature have been case reports or letters. Treatment is directed at local control. Metastases are extremely rare.

Pathophysiology

Basal cell carcinoma typically develops on sun-exposed skin and is most closely associated with ultraviolet radiation exposure. Given the paucity of ultraviolet radiation exposure in the male genitalia, the tumors are uncommon at this site. In addition to sun exposure, risk factors for basal cell carcinoma include ionizing radiation, arsenic ingestion, immunosuppression, and inherited syndromes such as nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum. The tumors are locally destructive but rarely metastasize.

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

The age at presentation ranges from 22-81 years, with most cases in older men. Most patients have fair skin, although cases in persons of color have also been reported. Most lesions have occurred on the shaft and scrotum and were present for years before the patient sought treatment. The lesion is papular or nodular, with pearly white borders and telangiectatic edges. Ulceration may be present. Biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. The histopathology shows nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, focal mucin, and areas of retraction artifact form the adjacent connective tissue stroma. See the image below.

Differential diagnoses

Primary squamous cell carcinomas (see Squamous Cell Carcinoma) must be excluded based on microscopic examination because of their more aggressive clinical course and potential for metastasis. Additional differential diagnoses include primary cutaneous adnexal carcinoma, such as eccrine porocarcinoma (see Eccrine Carcinoma). Malignant adnexal tumors tend to have a more aggressive microscopic growth pattern and higher rate of metastasis and require more aggressive treatment.

From a histopathological perspective, the basaloid variant of squamous cell carcinoma must be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma typically arises on the glans penis and exhibits much greater cytologic atypia. Definitive diagnosis is based on histopathologic examination.

Treatment

Treatment for basal cell carcinoma focuses on local excision or ablation. Mohs micrographic surgery has also been successful. [42] Topical therapy with imiquimod and 5-FU has shown success in limited studies. The treatment for basal cell carcinoma is in contrast to the more radical therapy used in the treatment of penile squamous cell carcinoma.

Outcome

For small lesions, complete excision of the tumor is generally curative. Incomplete treatment often results in local recurrence. Larger, more deeply infiltrative lesions can show significant local destruction, but metastasis is extremely rare.

Melanoma

Melanoma (see Malignant Melanoma) is an uncommon neoplasm of the male genitalia. Primary tumor sites include the penis, scrotum, and urethra. Melanoma accounts for less than 2% of primary malignant tumors of the penis. Scrotal and urethral tumors are even less frequent. Patients with melanoma of the male genitalia generally have a poor prognosis due to presentation at an advanced stage. [43]

Pathophysiology

Melanoma originates from epidermal or mucosal melanocytes. In a minority of cases, lesions are associated with a melanocytic nevus. Most patients present with advanced disease. Inguinal node metastases are common (43-62% of cases at presentation).

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

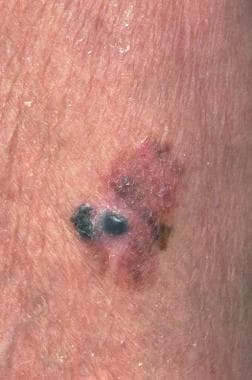

Men aged 50-70 years are generally affected. One series documented an age range of 57-77 years. [44] the prepuce (28%) and shaft (9%). [45] The lesions are typically asymmetric macules with irregular borders and variable pigmentation. Clinically evident inguinal lymph node enlargement is seen in a minority of patients. Biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis. The histopathologic features are similar to melanomas at other sites. Patients are staged according to the current (8th edition) AJCC melanoma staging system. [8] See the image below.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses include the following:

-

Melanoma in situ

-

Melanocytic nevi

-

Seborrheic keratosis

-

Lentigines

-

Melanosis

Treatment

Surgical excision is the primary treatment for melanoma of the male genitalia. Partial penectomy with or without inguinal lymph node dissection is the most common surgical therapy for penile and urethral tumors. Wide local excision is used to treat scrotal tumors. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is performed in some cases.

Outcome

As with melanoma at other sites, prognosis correlates with depth of tumor invasion and regional lymph node status. Because of the advanced stage at presentation, the prognosis for men with genital melanoma is poor, regardless of treatment. In one series of primary malignant melanoma of the penis and male urethra, seven of nine patients (two with lymph node metastases) died of disease within 3 years of presentation. [46, 43]

Scrotal melanoma is associated with a high mortality and late presentation. A systematic review noted that 18.75% of patients with scrotal melanoma presented with stage I/II disease, 56.3% with stage III disease and 25% with stage IV disease. Half of the patients developed metastatic disease and all the patients with distant organ metastases died. [47]

Although most patients with genital melanoma present with advanced stage disease, long-term survival has been demonstrated in patients with thin tumors who have no evidence of lymph node metastasis.

Kaposi Sarcoma

Although Kaposi sarcoma was once a rare neoplasm of the lower extremities in older men of Mediterranean descent, the incidence of the disease has increased 7000-fold in the HIV/AIDS era. Lesions of Kaposi sarcoma are very common in individuals infected with HIV and are often the presenting sign or symptom of HIV/AIDS. However, Kaposi sarcoma has become uncommon in patients infected with HIV who are treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

Pathophysiology

The specific histogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma has been controversial, but it now appears to be a vascular tumor of endothelial origin. Association of this vascular tumor with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8; Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) infection has been documented in HIV and non-HIV forms of disease. [48]

Clinical presentation/diagnosis

Kaposi sarcoma has been classified into four clinical groups, as follows:

-

Classic (endemic) form occurring in elderly men of Mediterranean descent

-

African Kaposi sarcoma

-

AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma

-

Immunosuppression-related Kaposi sarcoma

While the classic type was rarely seen in the genital area, approximately 20% of HIV-seropositive men with Kaposi sarcoma have genital involvement, and 3% of these patients present with genital involvement. Kaposi sarcoma presents as small violaceous-to-tan patches or nodules that may eventually coalesce to form plaques. Occasionally, lesions become exophytic or superficially ulcerated. Complications of genital involvement include lymphatic or urethral obstruction.

Skin biopsy is generally necessary for definitive diagnosis. Histopathology shows an atypical spindle-cell vascular proliferation with slitlike vascular channels and numerous extravasated erythrocytes.

Differential diagnoses

The clinical differential diagnoses of Kaposi sarcoma include the following:

-

Hemangioma

-

Angiosarcoma

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

-

Amelanotic melanoma

-

Dermatofibroma

-

Bacillary angiomatosis

Treatment

Although no cure has been identified, care is centered on limiting potential complications (obstruction) or cosmetic treatment. Topical alitretinoin, intralesional chemotherapeutics, radiation therapy, [49, 50] and local tissue destruction with cryotherapy or laser therapy [51] have been used with varying success. Optimizing the HIV antiviral regimen generally results in involution of Kaposi sarcoma in individuals infected with HIV. [52] Systemic chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin is frequently effective for patients with widespread disease or debilitating lesions.

Outcome

Although no cure is currently known, the use of multidrug antiviral regimens to treat patients infected with HIV can effectively induce involution of Kaposi sarcoma lesions.

-

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This lesion is large but mainly shows broad superficial invasion upon sectioning. The white jagged line is the fibrotic response to the invading tumor.

-

Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: This case obliterates the tip of the glans and distorts the prepuce. Note the large size, typical of these lesions at presentation.

-

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prepuce: The ulcerating tumor is noted to arise from a background of inflamed prepuce.

-

Nodular basal cell carcinoma (Image courtesy of Hon Pak, MD)

-

Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Image courtesy of Hon Pak, MD)

-

Malignant melanoma (Image courtesy of Hon Pak, MD)

-

Squamous cell carcinoma (Image courtesy of Hon Pak, MD)

-

Squamous cell carcinoma (Image courtesy of Hon Pak, MD)