Practice Essentials

Vulvar carcinoma encompasses any malignancy that arises in the skin, glands, or underlying stroma of the perineum, including the mons, labia minora, labia majora, Bartholin glands, or clitoris. (See the image below.) Tumors can also arise in ectopic breast tissue that can be located in the vulva along the milk line. Metastatic tumors to the vulva infrequently occur. For related information, see the Medscape Reference article Malignant Vulvar Lesions.

A large T2 carcinoma of the vulva crossing the midline and involving the clitoris. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

A large T2 carcinoma of the vulva crossing the midline and involving the clitoris. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

Signs and symptoms

The majority of patients present with a single vulvar lesion. Patients may complain of vulvar pruritus, pain, or irritation, although many patients are asymptomatic. Patients with advanced disease can present with enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, lower-extremity edema, or rectal bleeding.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Patients presenting with vulvar complaints should have a complete pelvic examination, including palpation for enlarged inguinal lymph nodes, vaginal speculum examination, and bimanual pelvic examination. A biopsy should be performed when any discrete lesion of the vulva is detected.

Imaging studies are useful to rule out metastatic disease for patients with large vulvar lesions and/or palpable inguinal lymph nodes. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is the most accurate modality to detect pelvic or para-aortic adenopathy in patients with vulvar cancer. [1]

See Workup for more detail.

Treatment

Resection of the primary lesion is the treatment of choice for vulvar carcinoma. Patients with inoperable primary tumors or fixed inguinal lymph nodes are candidates for preoperative treatment with chemotherapy and radiation.

See Treatment for more detail.

History of the Procedure

Patients with vulvar cancer, in the early part of the 20th century, usually died of disease. The overall survival rate for vulvar cancer after simple surgical excision was less than 25%. Attempts to improve outcomes for patients with vulvar cancer by performing more radical surgery were first described by Basset in 1912. [2] Way described an improved survival rate using an en bloc dissection radical vulvectomy with an inguinal and pelvic lymphadenectomy. [3] The Bassett-Way operation resulted in a 5-year survival rate of 74% as reported by Morley. [4] This success rate convinced most surgeons to use this operation for all patients with vulvar cancer regardless of tumor size. Major morbidity from this procedure included poor wound healing and chronic lymphedema.

Fred Taussig collected a large series of vulvar cancer cases from 1911-1940. [5] He initially started his series with a radical excision of the primary tumor with an en bloc dissection of the inguinal lymph nodes. Later, he modified his technique for patients with small lesions in an attempt to decrease operative morbidity. He used separate incisions for the groin dissection and the vulvar excision. This reduction in the volume of tissue removed in women with small lesions was not routinely used until Hacker reported his experience with 100 patients in 1981. [6] He reported using 3 separate incisions, as described by Taussig, for patients with clinical stage I disease. The 5-year survival rate was 97%.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Cancer of the vulva is the fourth most common malignancy of the female genital tract. The American Cancer Society estimates in 2023 there will be 6470 women diagnosed with vulvar cancer and 1670 deaths from this disease in the United States. [7]

International statistics

Unfortunately, the incidence of preinvasive disease of the vulva has almost doubled over the past decade, and this may translate into a marked increase in the incidence of invasive vulvar carcinoma in the future. Since vulvar cancer is rare and is not monitored by the World Health Organization, the global incidence of this disease is not precisely known.

Etiology

The incidence of vulvar carcinoma has a bimodal peak. Currently, development of vulvar carcinoma in situ in young women is suggested to correlate to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. In older women, the etiology of the carcinoma is attributed to chronic irritation or other poorly understood cofactors.

Risk factors

Estimates indicate that women who smoke cigarettes have a 4- to 5-fold increase in the incidence of carcinoma in situ of the vulva and a 20% increase in vulvar carcinoma. The incidence of vulvar carcinoma in situ and vulvar carcinoma is higher in women with multiple sexual partners and in women with a history of HPV infection. For women who report a history of genital warts or HPV-related disease, the relative risk for carcinoma in situ is 18.5 and for invasive cancer is 14.5.

Pathophysiology

The development of vulvar dysplasia and cancer in most patients is related to HPV infection. Certain strains of HPV are known to be more oncogenic than others. HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, and 54 are more likely to be associated with cervical neoplasia and cancer and are suspected to also be responsible for vulvar cancers. The DNA from HPV 16 and 18 has been detected in up to 60% of patients with vulvar cancer.

The mechanism of HPV transformation into dysplasia and cancer is not well understood. Two gene products from HPV are known to immortalize cells in culture and are probably responsible for malignant transformation. The HPV E6 protein does have the ability to bind the host p53 protein. The HPV E7 protein binds the Rb gene product. The oncogenic viral types are thought to have a greater affinity for these cellular proteins, which would explain the increased risk of malignant transformation. Some infections may lead to integration of the viral DNA into the host, with disruption of the normal regulation of the E6 and E7 oncoproteins. This increased production of the E6 and E7 gene products could then result in oncogenic transformation.

Presentation

Diagnosis of vulvar carcinoma is often delayed. Women neglect to seek treatment for an average of 6 months from the onset of symptoms. In addition, a delay in diagnosis often occurs after the patient presents to her physician. In many cases, a biopsy of the lesion is not performed until the problem fails to respond to numerous topical therapies. A biopsy should be performed when any discrete lesion of the vulva is discovered.

The most common presentation is a pruritic lesion of the vulva or a mass detected by the patient herself. However, early vulvar cancer may be asymptomatic and recognized only with careful inspection of the vulva. A biopsy should be performed on all visible lesions on the vulva. More advanced vulvar carcinomas present with bleeding, pain, or discharge.

A large squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Note the small contralateral "kissing lesion" that can be seen with vulvar carcinomas. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)

A large squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Note the small contralateral "kissing lesion" that can be seen with vulvar carcinomas. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)

Indications

Choosing the proper surgical procedure for vulvar cancer is important. Patients with vulvar dysplasia can have a wide local excision. The advantage of this procedure is pathologic examination of the removed tissue. Microscopic diagnosis allows for assessment of surgical margins and assures the absence of invasive disease. Ablative procedures may be appropriate to treat dysplastic lesions if vulvar cancer can be excluded with reasonable certainty.

A women with biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva is usually a candidate for surgical excision. Patients with a lesion involving the upper urethra or anus or is fixed to the pelvic bone can be treated with neoadjuvant radiation and chemotherapy prior to surgical intervention. [8] This type of therapy can allow future resection with preservation of the urethral or rectal sphincter in most cases. Radiation can also be used in an attempt to spare the clitoris.

Relevant Anatomy

The vulva includes all external genital structures, including the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vaginal vestibule, perineum, and supporting structures exterior to the urogenital diaphragm.

The femoral triangle is bounded by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the adductor longus medially, and the sartorius laterally. The superficial groin nodes lie above the cribriform fascia in the femoral triangle. Careful dissection generally reveals 5 vessels in the femoral triangle above the cribriform fascia, the largest of which is the saphenous vein. Often, a lateral accessory saphenous vein can be identified. The other vessels include the superficial circumflex, the superficial epigastric, and the external pudendal. Below the cribriform fascia are the deep inguinal nodes. Three to 4 nodes can be found medial to the femoral vein. The most superior of these is the sentinel node to the pelvic lymphatics and is known as the node of Cloquet.

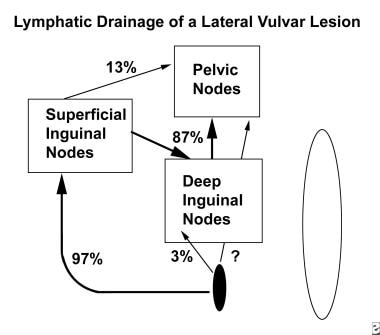

The lymphatics of the vulva and distal third of the vagina drain into the superficial inguinal node group and travel through the deep femoral lymphatics and the node of Cloquet to the pelvic nodal groups (see image below). [9] Direct spread to the deep nodal groups without metastasis to the superficial group has been documented using lymphatic mapping. This type of direct spread is uncommon and represents fewer than 5% of cases.

Diagram of lymphatic drainage of a lateral lesion. Most lymphatics flow through the superficial inguinal nodes, deep inguinal nodes, and the node of Cloquet to the pelvic lymph node chains. Deep inguinal node findings are positive approximately 3% of the time when superficial inguinal node findings are negative. Lymphatic mapping studies indicate that 13% of cases demonstrate findings consistent with flow to the pelvis that does not involve the node of Cloquet. If the lesion is in the anterior labia minor, then contralateral flow is demonstrated in 67% of cases.

Diagram of lymphatic drainage of a lateral lesion. Most lymphatics flow through the superficial inguinal nodes, deep inguinal nodes, and the node of Cloquet to the pelvic lymph node chains. Deep inguinal node findings are positive approximately 3% of the time when superficial inguinal node findings are negative. Lymphatic mapping studies indicate that 13% of cases demonstrate findings consistent with flow to the pelvis that does not involve the node of Cloquet. If the lesion is in the anterior labia minor, then contralateral flow is demonstrated in 67% of cases.

Lymphatic mapping studies have also demonstrated that radioactive colloid injected into the vulva can accumulate more readily in the lateral external iliac nodes than in the medial group, which suggests that not all lymphatics flow to the medial pelvic nodes through the node of Cloquet. Studies suggest that 10-20% of lymphatic flow from the superficial node group travels directly to the pelvis without passage through the deep inguinal nodes. A direct pathway from the clitoris or vulva to the pelvic nodes has not been identified.

Contraindications

Resection of the primary lesion is the treatment of choice because few alternatives to surgery are available for vulvar carcinoma. Regional or general anesthesia can be used for this type of surgery. Patients with inoperable primary tumors or fixed inguinal lymph nodes are candidates for preoperative treatment with chemotherapy and radiation. [10] This treatment modality often reduces tumor volume and improves the chances for surgical resection. The morbidity of this regimen is substantial. [11]

Radiation alone can be used for palliation but should not be considered a curative treatment.

Prognosis

Overall survival for patients with vulvar carcinoma is excellent, especially in those with early-stage disease. Experience with modern treatment from the Mayo clinic shows that the overall survival rate for women with vulvar carcinoma is 75%, compared to an 89% actuarial survival rate for age-matched controls. The 5-year survival rates after surgery for vulvar cancer are as follows:

-

Stage I - 90%

-

Stage II - 81%

-

Stage III - 68%

-

Stage IV - 20%

Tantipalakorn and colleagues published their results in 121 patients with stage I and II squamous cell carcinoma in 2009. There was no difference in survival rates between patients with stage I and stage II disease. The 5-year actuarial survival for stage I disease was 97% compared with 95% for stage II disease. More than 95% of these patients were treated with vulvar-conserving surgery. [12]

-

Diagram of lymphatic drainage of a lateral lesion. Most lymphatics flow through the superficial inguinal nodes, deep inguinal nodes, and the node of Cloquet to the pelvic lymph node chains. Deep inguinal node findings are positive approximately 3% of the time when superficial inguinal node findings are negative. Lymphatic mapping studies indicate that 13% of cases demonstrate findings consistent with flow to the pelvis that does not involve the node of Cloquet. If the lesion is in the anterior labia minor, then contralateral flow is demonstrated in 67% of cases.

-

A large T2 carcinoma of the vulva crossing the midline and involving the clitoris. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

-

Specimen after removal with at least 1 cm margins around the tumor. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

-

The surgical defect after a radical vulvectomy specimen is removed. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

-

The surgical defect is closed after a radical vulvectomy. (Photograph courtesy of Tom Wilson)

-

A large squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Note the small contralateral "kissing lesion" that can be seen with vulvar carcinomas. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)

-

A specimen from a traditional single-incision radical hysterectomy. Most radical vulvectomies are now performed through 3 incisions, with the groin nodes removed separately from the vulvectomy specimen. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)

-

Closure of a large single-incision radical vulvectomy. The complete wound breakdown rate from this procedure is often greater than 50%. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)

-

A specimen from a primary exenteration for a stage IVA vulvar cancer involving the rectum. Many of these large tumors are now treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation prior to surgery, with preservation of rectal sphincter function. (Photograph courtesy of James B. Hall, MD)