Practice Essentials

Vaginal vault prolapse refers to significant descent of the vaginal apex following a hysterectomy. Although the term enterocele refers to a hernia in which peritoneum and abdominal intestinal contents are in direct contact with and displace the vaginal epithelium, with massive vaginal eversion it is often difficult to determine what lies behind the vagina (bladder, small intestine, colon, or rectum). The terms anterior vaginal wall prolapse, vaginal vault prolapse, and posterior vaginal wall prolapse are preferred for this reason. [1]

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common healthcare problem that many women live with for years, causing discomfort and affecting quality of life. Massive vaginal eversion, rare compared with mild to moderate POP, can lead to devastating consequences if not handled appropriately. This article will discuss the presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of POP, with a focus on massive vaginal eversion and enterocele (also known as advanced posthysterectomy pelvic organ prolapse).

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include the following:

-

Prolapse: Vaginal bulging, pelvic pressure, vaginal bleeding, infection, discharge, tenderness, low back pain

-

Anorectal: Constipation, feeling of incomplete bowel emptying, straining to defecate, splinting or digitation, fecal urgency

-

Urinary: Incontinence, occult incontinence, urgency, frequency, recurrent urinary tract infection, slowed urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittent stream, splinting to micturate, dysuria

-

Sexual: Dyspareunia, obstructed intercourse, vaginal laxity, loss of or decreased libido

The following are characteristic signs:

-

Advanced stage III C or IV C on the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POP-Q)

-

Breaks in the rectovaginal fascia often noted on digital rectovaginal examination

-

Levator and pelvic floor muscle defects, often with decreased Kegel strength

-

Occult urinary incontinence with prolapse reduction

-

Postvoid residual urine

See Presentation for more detail.

Presentation and diagnosis

The history and physical examination are generally all that are needed to obtain a diagnosis of vaginal vault eversion. Questions about the quality and duration of prolapse and urinary, fecal, and sexual symptoms should be asked and validated questionnaires given. The physical examination should focus on the stage of prolapse based on the POP-Q examination along with any obvious pathology, such as abdominal masses or ascites, vaginal wall breakdown, fistulas, or infection.

Imaging may be used to determine which organs are behind the vaginal wall prolapse or to examine for intra-abdominal pathology but should not routinely be employed.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Conservative options are observation, pessary placement, and pelvic floor physical therapy.

The following are surgical treatment options:

-

Reconstructive: Sacrospinous ligament, uterosacral ligament, iliococcygeal fixation, sacral colpopexy

-

Obliterative: Colpocleisis of the vaginal vault

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Massive vaginal vault prolapse is a devastating condition, with discomfort and genitourinary and defecatory abnormalities as the primary consequences. Pelvic organ prolapse is prevalent and associated with significant health-related quality of life and economic impact. [2] References to prolapse of the womb were first made in ancient Egypt, dating back to 1550 BC. Vaginal vault prolapse refers to significant descent of the vaginal apex following a hysterectomy (see the image below), whereas uterovaginal prolapse denotes apical prolapse of the cervix, uterus, and proximal vagina.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Massive vaginal eversion in a patient with post hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Massive vaginal eversion in a patient with post hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

These apical failures are often accompanied by anterior and/or posterior vaginal compartment prolapse with or without enterocele. While the term enterocele refers to a hernia in which peritoneum and abdominal intestinal contents are in direct contact with and displace the vaginal epithelium, with massive vaginal eversion it is often difficult to determine what lies behind the vagina (bladder, small intestine, colon, or rectum). The terms anterior vaginal wall prolapse, vaginal vault (or apical) prolapse, and posterior vaginal wall prolapse are preferred for this reason, as they are descriptive of what is being observed. [1]

Although this is not a new condition, apical prolapse is thought to be increasingly common as life expectancy increases. According to population projections from the US Census Bureau from 2010 to 2050 and published age-specific prevalence estimates for bothersome, symptomatic pelvic floor disorders and pelvic organ prolapse, the number of women with uterovaginal prolapse is expected to increase from 3.3 to 4.9 million from 2010 to 2050. [3]

Whereas complete vaginal eversion is obvious on physical examination, lesser degrees of prolapse and the presence of enterocele are more difficult to discern and require careful evaluation of all anterior, posterior, and apical compartment defects. Also, associated functional abnormalities, whether concurrent or potential, must be properly explored, evaluated, discussed with the patient, and considered in the context of management.

Problem

The International Urogynecological Association and International Continence Society define pelvic organ prolapse as the descent of one or more of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of vagina (vaginal vault or cuff scar after hysterectomy). [1, 4] Indeed, a degree of uterine/vaginal descensus is present in many, if not most, women who are multiparous. Not all patients with prolapse are symptomatic, and the degree of prolapse often does not correlate with the degree of symptoms reported by the patient. Furthermore, pelvic floor–related symptoms do not predict the anatomic location of the prolapse especially in women with mild to moderate prolapse. [5] A systematic and comprehensive description of pelvic organ prolapse is useful to help document and communicate the severity of the problem, to establish treatment guidelines, and to improve the quality of research to standardizing definitions.

The pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system was developed to address deficiencies in measuring and reporting the extent of prolapse. Specific sites are defined separately on the anterior, posterior, and apical vaginal compartments and are measured with respect to a fixed reference point, the hymen. These measurements can then be categorized into an ordinal staging system ranging from 0-4:

-

Stage 0 denotes no prolapse (the apex can descend as far as 2 cm relative to the total vaginal length).

-

Stage 1 means that the most distal portion of the prolapse descends to a point more than 1 cm above the hymen.

-

Stage 2 denotes that the maximal extent of the prolapse is within 1 cm of the hymen (outside or inside the vagina).

-

Stage 3 means that the prolapse extends more than 1 cm beyond the hymen, but no more than within 2 cm of the total vaginal length.

-

Stage 4 denotes complete eversion, which is defined as extending to within 2 cm of the total vaginal length.

The POP-Q staging system has been validated and demonstrates good interobserver and intraobserver reliability. [4] Although POP-Q staging adequately addresses the extent of prolapse, assumptions about which organ is behind the visualized bulge should be made with caution and should be made only after a complete evaluation.

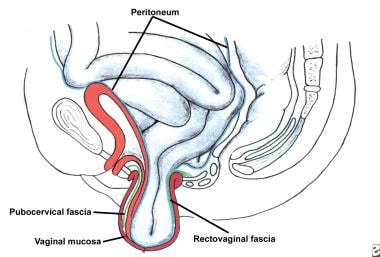

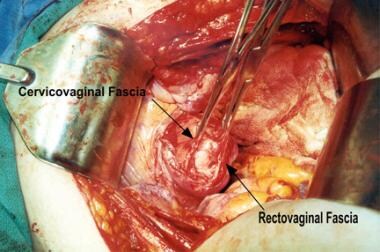

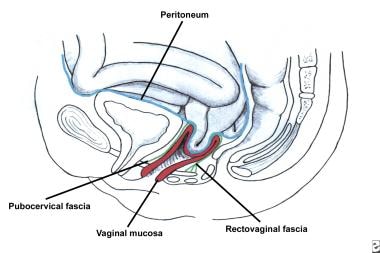

Regarding enterocele, the definition is somewhat more difficult. Previous texts have defined enterocele as a hernia in which peritoneum and abdominal contents displace the vagina and is palpable within the cul-de-sac, as evaluated during a rectovaginal examination in the erect position. Patients with such findings may have a deep cul-de-sac and thus represent a normal variant. A more anatomic definition was proposed by Richardson, who suggested that enterocele occurs when endopelvic fascia does not intervene between the peritoneum and vagina (see the image below). [6]

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Large apical endopelvic fascial defect representing an enterocele demonstrated by the transabdominal route. Note the proximal cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia separate from the peritoneum.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Large apical endopelvic fascial defect representing an enterocele demonstrated by the transabdominal route. Note the proximal cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia separate from the peritoneum.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) when defined by symptoms has prevalence of 3-6% and up to 50% when based upon vaginal examination. Moreover, the prevalence of surgical correction of the prolapse varies widely from 6% to 18%, with the incidence of POP surgery from 1.5 to 1.8 per 1,000 women years and peaks in women aged 60-69 years. [7]

Swift reported on the frequency of different stages of pelvic organ prolapse in a routine gynecologic clinic population based upon the POP-Q staging system. Most women had stage 1 or stage 2 prolapse (43.3% and 47.7%, respectively), few women had stage 0 or stage 3 prolapse (6.4% and 2.6%, respectively), and none had stage 4 POP. [8]

Samuelsson et al reported a prevalence of 30.8% for any prolapse, using the Baden-Walker halfway system, in a study of the general population in Sweden. [9] In a population-based Dutch study, the prevalence of POP based on POP-Q staging was as follows: stage 0 = 25.0%; stage I = 36.5%; stage II = 33%, stage III = 5.0%; stage IV = 0.5%. [10] .

Vaginal vault prolapse is thought to occur postoperatively in 0.5% of hysterectomy cases. [9] A study found only a small difference in the risk of POP repair after hysterectomy when comparing the different hysterectomy types after restricting the analyses to women without POP at the time of hysterectomy. In this study, patients who underwent a vaginal hysterectomy had a slightly higher risk (odds ratio [OR], 1.25) of requiring a POP repair in the future compared with laparoscopic or open abdominal hysterectomies. [11]

Etiology

Current evidence supports a multifactorial etiology of POP. Swift reported that significant trends for increasing prolapse were found with advancing age, parity, postmenopausal status, previous hysterectomy, and prior corrective surgery for prolapse. [8] Multivariate analysis in a study performed by Samuelsson et al revealed independent statistical associations with age, parity, maximal birth weight, and pelvic floor muscle strength. [9] Such associations were not found regarding weight or hysterectomy status. Some epidemiologic evidence contradicts the opinion that female pelvic organ prolapse worsens with age. [9] Furthermore, Sze et al demonstrated that vaginal birth is not associated with POP-Q stages III and IV prolapse, but it is associated with an increase in POP-Q stage II. [12]

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and constipation have been associated with the development of POP. The mechanism is likely from an increase in abdominal pressure due to chronic coughing or straining with bowel movements contributing to prolapse development. [13] Several studies have found an association between obesity and POP, with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 increasing the risk of prolapse up to 75%. [14]

It is well recognized that POP runs in families, giving credence to a hereditary contribution to the phenotype with some evidence that loci on chromosomes 10q and 17q may contribute to the etiology of prolapse. [15, 16, 17, 18] Additionally, a recent paper reported on the first set of genome-wide significant POP variants identified through genome-wide associate study (GWAS). [19] This study showed a genetic overlap between POP and several traits with similar pathophysiology pointing toward a role of estrogen exposure and connective tissue metabolism in the etiology of POP.

Racial differences have been reported for pelvic organ prolapse, although is not yet clear whether the differences are biological or sociocultural. Whitcomb et al showed that compared with African American women, Latina and white women had a 4 to 5 times higher risk of symptomatic prolapse, and white women had 1.4-fold higher risk of objective prolapse at or beyond the hymen. [2] More recently, data obtained from African American and Hispanic women who were enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy, with available genotyping data from Women’s Health Initiative-SHARe, suggest that common germ-line variations may contribute to an increased risk of POP among African Americans and Hispanics; however, further research with larger minority sample sizes is necessary to confirm this finding. [20]

Pathophysiology

As discussed, genetic factors may play a significant role in development of uterovaginal prolapse. Current basic science research suggests a molecular etiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Some studies demonstrate an increased rate of apoptosis and significant depletion of mitochondrial DNA in uterosacral ligaments in women with uterovaginal eversion. [21, 22]

The precise etiology of pelvic organ prolapse remains elusive. Additional theories include diminished sacral nerve function and/or defects in collagen. The pelvic floor is a unique and complex system constructed of skeletal and striated muscles, support and suspensory ligaments, fascial layers and an intricate neural network. When this system is damaged, pelvic floor failure may occur and pelvic organ prolapse ensues. [23]

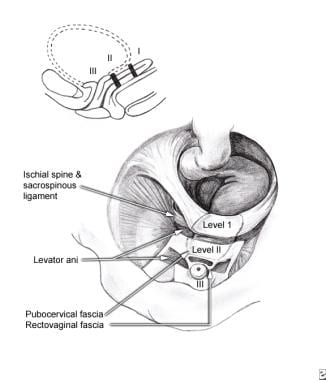

DeLancey describes the anatomy of vaginal vault prolapse in terms of 3 levels of support (see the image below). [24]

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Levels of support as described by DeLancey (1992). Note that level I refers to apical (or uterovaginal) support.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Levels of support as described by DeLancey (1992). Note that level I refers to apical (or uterovaginal) support.

The 3 levels of support shown in the image are as follows:

-

Level I refers to the support of the upper vagina and cervix or the vaginal cuff (in a woman who has undergone total hysterectomy) by the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex.

-

Level II denotes the lateral support of the mid vagina to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (white line).

-

Level III is represented by the fusion of tissue along the base of the urethra and the distal rectovaginal septum to the perineal body.

The conditions of enterocele and vaginal eversion represent failures of level I support, although other compartments may be affected. Uterovaginal prolapse does not denote intrinsic uterine disease and, therefore, may not necessarily require a hysterectomy in all cases. It should be noted, however, that no evidence proves or disproves the benefit of hysterectomy at the time of apical suspension.

Apical prolapse occurs because of tearing (or attenuation) of the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex. This results in failure to support the upper vagina and/or uterus over the pelvic diaphragm, which should be in a near-horizontal plane in a woman in the erect position. Level I support is considered primary in maintaining adequate overall pelvic support.

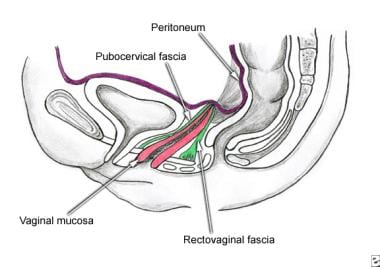

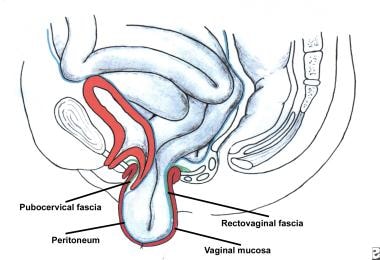

Richardson describes an enterocele in anatomic terms, as a break in the integrity of endopelvic fascia at the vaginal apex (see the image below). [25]

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Normal posthysterectomy vaginal vault. Note the presence of continuity of the endopelvic fascia at the vaginal apex, resulting from the fusion of cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia, and their fusion with the uterosacral ligament portion of endopelvic fascia.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Normal posthysterectomy vaginal vault. Note the presence of continuity of the endopelvic fascia at the vaginal apex, resulting from the fusion of cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia, and their fusion with the uterosacral ligament portion of endopelvic fascia.

Normally, post-hysterectomy enterocele is precluded by the apposition of pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia (collectively termed endopelvic fascia) at the apex. Anterior, apical, and posterior enteroceles have been described based upon the location of the fascial defect and the location of the ensuing herniation of bowel.

Apical enterocele is the most common enterocele and is primarily associated with post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Apical enterocele may present with or without vaginal vault prolapse (see the images below).

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Early enterocele with no vault prolapse. Note contact of peritoneal contents with vaginal epithelium, with no intervening endopelvic fascia.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Early enterocele with no vault prolapse. Note contact of peritoneal contents with vaginal epithelium, with no intervening endopelvic fascia.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Progressive enterocele now demonstrating true vaginal vault prolapse.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Progressive enterocele now demonstrating true vaginal vault prolapse.

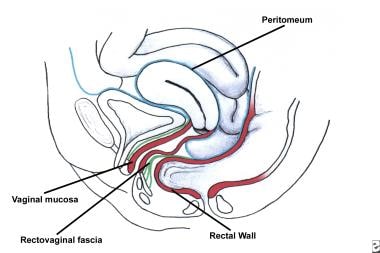

Anterior enteroceles are rare and may occur following sacrospinous ligament fixation, when the proximal vagina is displaced posteriorly, creating a potential space in the anterior compartment. Because they present as a protrusion of the anterior vaginal wall, they may be the true etiology of some cystoceles. In women with an intact uterus, posterior enteroceles have been described. These are thought to be due to tearing of the proximal rectovaginal fascia from its attachment to the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex, which results in descent of the peritoneal contents down the posterior aspect of the vagina (see the image below). On examination, this is often associated with loss of posterior vaginal rugae proximally.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Posterior enterocele in a patient with a uterus. Note that peritoneal contents have dissected between the vaginal skin and rectovaginal fascia through a proximal defect.

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Posterior enterocele in a patient with a uterus. Note that peritoneal contents have dissected between the vaginal skin and rectovaginal fascia through a proximal defect.

Posterior enterocele is usually accompanied by significant uterovaginal prolapse and prolapse of other compartments as well. [25]

Histologic studies by Tulikangas et al failed to find breaks in the fibromuscular layer in women who underwent surgical correction for enterocele compared with controls (women who did not have pelvic organ prolapse). [26] Admittedly, the authors' findings did not correlate with their subjective clinical findings of thinning of the vaginal wall in enteroceles. Hsu et al similarly found a lack of difference in vaginal wall thickness on MRI studies of patients with prolapse and their normal controls. [27] The numbers in these studies, however, were small and further investigation is needed before this controversy is fully resolved. Nonetheless the authors believe that considering this theory in the context of surgical correction has merit and aids in properly managing these conditions.

Presentation

Patients may present with an obvious vaginal bulge that is visualized or felt by the patient. Patients may complain of the feeling that they are "sitting on a ball." Conversely, the patient may report a vague sense of pelvic heaviness, back pain, or a sensation that something is about to fall out. The bulging is often noted to be worse toward the end of the day, as compared with when the patient first wakes up, or when the patient is straining at defecation, urination, or with exercise. When vaginal epithelium remains exteriorized, it undergoes cornification and, often, ulceration, which can result in significant pain, vaginal bleeding, discharge, and infection.

Functional difficulties may be encountered during coitus, especially with massive vaginal eversion. Dyspareunia and obstructed intercourse may lead to decreased libido given negative body image. Defecation may be difficult; associated constipation is very common and patients may push inside the vagina (splinting/digitation) to evacuate their bowels. Patients may have to strain in order to complete a bowel movement or empty their bladder.

Incomplete bladder emptying also is common, and in severe cases, complete obstruction may occur. Voiding dysfunction may result in frequent urinary tract infections and urinary urgency or frequency with or without incontinence due to incomplete emptying. A slow stream with intermittent urine flow or hesitancy may be described by the patient and there may be a need for splinting to void. Due to kinking of the urethra, occult (potential) stress incontinence and even intrinsic sphincter deficiency may be present. A history of stress incontinence that spontaneously improved and/or resolved as the prolapse progressively worsened is especially concerning for the presence of occult stress incontinence. In a cross-sectional study, urinary urge incontinence was associated with anterior wall prolapse, whereas stress urinary incontinence was strongly linked to posterior wall prolapse. [5] Advanced pelvic prolapse may result in ureteral kinking with the potential for hydroureter. [28]

A systematic review showed that with stage II prolapse or higher, the risk of hydronephrosis can be up to 63.1%. [29] This review concluded that hydronephrosis was more common in patients with more severe prolapse, in those with uterovaginal prolapse as opposed to vaginal vault prolapse, and in those with a longer duration of prolapse.

Indications

Treatment of pelvic organ prolapse is indicated if it is symptomatic or is causing associated morbidity. Asymptomatic prolapse, with minor degrees of protrusion that cause no other problems, must be discussed with the patient, but does not necessarily require treatment after ruling out significant associated functional problems (urinary retention, obstipation, etc). In the older population, even extensive prolapse may be reported as asymptomatic by the patient herself, but questioning her family or caregiver may reveal troublesome symptoms, and further evaluation may reveal significant resultant morbidity.

Offer conservative management to these patients as the initial management option. Conservative management may include observation with mild degrees of asymptomatic prolapse or a pessary fitting. Pelvic floor physical therapy is another conservative option and may be utilized with some success in mild to moderate prolapse for both objective and subjective symptoms. [30, 31, 32] It should be noted that massive vaginal eversion cannot be treated or reversed with the use of pelvic floor exercises or physical therapy. Surgical management may be considered in appropriate candidates if conservative therapies fail or are declined by the patient.

Relevant Anatomy

The cardinal-uterosacral ligaments are localized thickenings of the peritoneum and connective tissue that invest the pelvic organs. The endopelvic fascia that is anterior to the vagina is called pubocervical; posteriorly, it is termed rectovaginal fascia or Denonvilliers fascia. Laterally, the endopelvic fascia attaches the vagina to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (white line) to provide lateral support to the mid-vaginal compartment, whereas the distal rectovaginal fascia attaches laterally to the aponeurosis of levator ani. [33]

The integrity of the vaginal apex following hysterectomy depends on the fusion of the pubocervical fascia with the rectovaginal fascia and support provided by the uterosacral ligaments. As described above, it is the gap between these two layers of fascia, no longer connected by the strength of the pericervical ring that allows for bowel to slip between the layers leading to an enterocele. [24] Surgically, the uterosacral ligaments lie medial to the ureters in the pelvis. The proximal uterosacral ligament fans out and attaches to the lateral aspect of the sacrum. MRI studies show slight variations in the attachment of the uterosacral ligament, although most overlay the sacrospinous ligament/coccygeus muscle. The proximal vagina usually points into the hollow of the sacrum towards S3 and S4 and maintains a near-horizontal plane when the woman stands erect.

Although the term fascia is frequently used to denote the surgically significant layer used for pelvic reconstruction, histologically, it is a fibromuscular layer with varying amounts of smooth muscle, collagen, and elastin that is located deep to the epithelium.

Contraindications

Regarding treatments, pessary use is contraindicated in the presence of vaginal ulceration and breakdown or in the presence of an active vaginal infection. Severe vaginal atrophy is best treated prior to starting pessary use, in the absence of contraindications for estrogen use. Additionally, if a patient or caregiver is unable to remove and reinsert the pessary or bring the patient in for periodic vaginal examinations, a pessary should not be placed. Pelvic floor physical therapy has no absolute contraindications; however, it has not been found to be successful for high-grade prolapse. See Treatment/Medical Therapy for more details on treatment options.

The medical evaluation of a patient for surgical repair is a topic that is too broad for this article. However, one should tailor the proposed operation to the specific defects noted preoperatively, taking into consideration the patient's overall health and prior surgical history. The chosen approach, whether vaginal, abdominal, laparoscopic, or robotically assisted, should be selected with careful consideration of these patient-related points, in addition to the surgeon's level of skill and available local resources. Appropriate consultations and referrals during the preoperative evaluation can ensure the highest degree of success and safety.

Prognosis

The natural history of pelvic organ prolapse has been studied in prospective observational studies in postmenopausal women. [14] In one study, there was both regression and progression of the prolapse in older women, but rates of vaginal descent progression were greater than regression. Increasing BMI and grand multiparity increase the risk of progression. A longitudinal analysis also suggested that vaginal descent progression over time is positively associated with various bladder, bowel, and prolapse symptoms in postmenopausal women with stage I-II prolapse. [34]

It should be noted that most studies following the natural history of pelvic organ prolapse focus on early-stage prolapse, and it is highly unlikely that massive vaginal eversion will regress with time. As mentioned above, if massive vaginal eversion is not treated appropriately, more severe sequelae such as ulceration, bleeding, hydronephrosis, and kidney damage, as well as vaginal vault evisceration, are possible. [35]

Massive vaginal eversion may present with acute findings that necessitate operative urgent/emergent management. Generally, complications such as ulceration, vaginal epithelial bleeding, and tenderness are likely to occur with long-standing advanced-stage prolapse.

Patient Education

Patients should be educated about their suspected etiology and physical examination findings. Often patients are reluctant to bring up issues such as pelvic organ prolapse to their primary care providers who would be able to refer them to a urogynecologist. If they have not had a vaginal examination, many patients may live with this condition for years with a great impact on their quality of life. It is important to validate their concerns and to provide both conservative and surgical options for treatment.

The American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association have a large volume of patient resources that can be found at the following websites:

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Large apical endopelvic fascial defect representing an enterocele demonstrated by the transabdominal route. Note the proximal cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia separate from the peritoneum.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Levels of support as described by DeLancey (1992). Note that level I refers to apical (or uterovaginal) support.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Normal posthysterectomy vaginal vault. Note the presence of continuity of the endopelvic fascia at the vaginal apex, resulting from the fusion of cervicovaginal and rectovaginal fascia, and their fusion with the uterosacral ligament portion of endopelvic fascia.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Early enterocele with no vault prolapse. Note contact of peritoneal contents with vaginal epithelium, with no intervening endopelvic fascia.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Progressive enterocele now demonstrating true vaginal vault prolapse.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Massive enterocele with total vaginal vault prolapse.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Posterior enterocele in a patient with a uterus. Note that peritoneal contents have dissected between the vaginal skin and rectovaginal fascia through a proximal defect.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Sacrospinous ligament fixation. The right sacrospinous ligament is being penetrated using the Nichols-Veronikis ligature carrier.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. The anatomy surrounding the right ischial spine.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Note the pudendal neurovascular bundle at the lateral aspect of the sacrospinous ligament. Also note the proper penetration of the suture into the body of the coccygeus muscle.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Following penetration of the sacrospinous ligament, the permanent suture (on the left) is attached to the posterior vagina by a figure-eight stitch, incorporating rectovaginal fascia but not penetrating the epithelium. Once this stitch is tied, a pulley has been created whereby the vagina can be drawn up to the ligament by pulling on the free suture and then tied down. The delayed absorbable suture is driven through-and-through and is tied on the vagina.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Depiction of completed fascial reconstruction with uterosacral reattachment in the sagittal view. Note that the vaginal apex has been restored to its normal anatomic location and is directed to the hollow of the sacrum.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. LeFort colpocleisis begins with dissection and excision of a rectangular patch of epithelium on both the anterior and posterior vagina. Gradual inversion of the vaginal tube is accomplished by interrupted sutures that approximate anterior to posterior. Reapproximation of the lateral vaginal edges serves to maintain the tunnels on either side of the repair. From Thompson JD. Surgical correction of defects in pelvic support. In: Rock JR, Thompson JD, eds. TeLinde's Operative Gynecology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1997.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Transabdominal repair of the large enterocele noted in Image 2. Note interrupted permanent sutures used for repair.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Mesh configuration for abdominal sacral colpopexy. Mesh may come preformed or made in the operating room from two pieces of polypropylene mesh. If so, the crux of the Y is formed by permanent sutures with the knots tied down on the side that faces the sacrum, not the vagina.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Note the anatomy of the lower presacral space. Take care to adequately mobilize the sigmoid colon and ensure the safety of the right ureter. Identification of the middle sacral vessels is important to avoid hemorrhage.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Note adequate bites taken into the anterior sacral fascia at sacral level 2 (S2). Take care not to attach the mesh too high (towards the sacral promontory) so that the normal vaginal axis is maintained. Also, take care to avoid excess tension on the vagina.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Note the axis of the vagina and the attachment of the mesh to the sacrum at sacral level 3 (S3).

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Bilateral uterosacral reattachment has been performed laparoscopically with a permanent suture in a patient who desired retention of the uterus.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Massive vaginal eversion in a patient with post hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. A variety of pessaries that are available for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Uterosacral ligament suspension.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Iliococcygeus fixation.

-

Enterocele and massive vaginal eversion. Note the axis of the vagina and the attachment of the mesh to the sacrum.