Practice Essentials

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) refers to a condition in which a fetus is unable to achieve its genetically determined potential size. This functional definition seeks to identify a population of fetuses at risk for modifiable but otherwise poor outcomes. This definition intentionally excludes fetuses that are small for gestational age (SGA) but are not pathologically small. SGA is defined as growth at the 10th or less percentile for weight of all fetuses at that gestational age. Not all fetuses that are SGA are pathologically growth restricted and, in fact, may be constitutionally small. Similarly, not all fetuses that have not met their genetic growth potential are in less than the 10th percentile for estimated fetal weight (EFW).

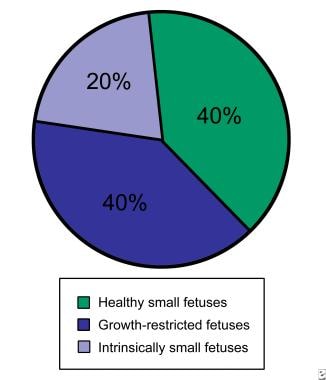

Of all fetuses at or below the 10th percentile for growth, only approximately 40% are at high risk for potentially preventable perinatal death (see image below). Another 40% of these fetuses are constitutionally small. Because this diagnosis may be made with certainty only in neonates, a significant number of fetuses that are healthy but SGA will be subjected to high-risk protocols and, potentially, iatrogenic prematurity.

The remaining 20% of fetuses that are SGA are intrinsically small secondary to a chromosomal or environmental etiology. Examples include fetuses with trisomy 18, cytomegalovirus infection, or fetal alcohol syndrome. These fetuses are less likely to benefit from prenatal intervention, and their prognosis is most closely related to the underlying etiology.

The clinician's challenge is to identify fetuses with FGR whose health is endangered in utero because of a hostile intrauterine environment and to monitor and intervene appropriately. This challenge also includes identifying small but healthy fetuses and avoiding iatrogenic harm to them or their mothers.

Causes of Fetal Growth Restriction

Maternal causes of FGR include the following [1] :

-

Chronic hypertension

-

Cyanotic heart disease

-

Class F or higher diabetes

-

Hemoglobinopathies

-

Autoimmune disease

-

Protein-calorie malnutrition

-

Smoking

-

Substance abuse

-

Uterine malformations

-

Thrombophilias

-

Prolonged high-altitude exposure

Placental or umbilical cord causes of FGR include the following:

-

Placental abnormalities

-

Chronic abruption

-

Abnormal cord insertion

-

Cord anomalies

-

Multiple gestations

Fetal causes of FGR include the following:

-

Chromosomal disorders

-

Congenital malformations

FGR occurs when gas exchange and nutrient delivery to the fetus are not sufficient to allow it to thrive in utero. This process can occur primarily because of maternal disease causing decreased oxygen-carrying capacity (eg, cyanotic heart disease, smoking, hemoglobinopathy), a dysfunctional oxygen delivery system secondary to maternal vascular disease (eg, diabetes with vascular disease, hypertension, autoimmune disease affecting the vessels leading to the placenta), or placental damage resulting from maternal disease (eg, smoking, thrombophilia, various autoimmune diseases).

Evaluation of causative factors for intrinsic disorders leading to poor growth may include a fetal karyotype, maternal serology for infectious processes, and an environmental exposure history.

Perinatal Implications

FGR causes a spectrum of perinatal complications, including fetal morbidity and mortality, iatrogenic prematurity, fetal compromise in labor, need for induction of labor, and cesarean delivery. In a cohort study in Sweden, a 10-fold increase in late fetal deaths was found among very small fetuses. [2] Similarly, Gardosi et al noted that nearly 40% of stillborn fetuses that were not malformed were SGA. [3]

Fetuses with FGR who survive the compromised intrauterine environment are at increased risk for neonatal morbidity. Morbidity for neonates with FGR includes increased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis, thrombocytopenia, temperature instability, and renal failure. These disorders are thought to occur as a result of the alteration of normal fetal physiology in utero.

With limited nutritional reserve, the fetus redistributes blood flow to sustain function and to help in the development of vital organs. This is called the brain-sparing effect and results in increased relative blood flow to the brain, heart, adrenals, and placenta, with diminished relative flow to the bone marrow, muscles, lungs, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and kidneys. The brain-sparing effect may result in different fetal growth patterns.

Campbell and Thoms introduced the idea of symmetric versus asymmetric growth. [4] Symmetrically small fetuses were thought to have some sort of early global insult (eg, aneuploidy, viral infection, fetal alcohol syndrome). Asymmetrically small fetuses were thought to be more likely small secondary to an imposed restriction in nutrient and gas exchange.

Investigators since then have disagreed on the importance of this differentiation. Dashe et al examined this issue among 1364 infants who were SGA (20% were asymmetrically grown, 80% symmetrically grown) and 3873 infants who were in the 25-75th percentile (ie, appropriate for gestational age). [5] The Table includes a selected list of statistically significant perinatal outcomes and events among these groups.

Table. Perinatal Events and Outcomes (Open Table in a new window)

Event |

Asymmetrically SGA |

Symmetrically SGA |

Appropriate for Gestational Age |

Anomalies |

14% |

4% |

3% |

Survivors - No serious morbidity |

86% |

95% |

95% |

Labor induction (< 36 wk) |

12% |

8% |

5% |

Intrapartum high blood pressure (< 32 wk) |

7% |

2% |

1% |

Cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

15% |

8% |

3% |

Intubated in delivery room |

6% |

4% |

3% |

Neonatal intensive care unit admission |

18% |

9% |

7% |

Respiratory distress syndrome |

9% |

4% |

3% |

Intraventricular hemorrhage (grade III or IV) |

2% |

< 1% |

< 1% |

Neonatal death |

2% |

1% |

1% |

Gestational age at delivery |

36.6 wk ± 3.5 wk |

37.8 wk ± 2.9 wk |

37.1 wk ± 3.3 wk |

Preterm birth ≤ 32 wk |

14% |

6% |

11% |

The symmetrically grown infants who were SGA had outcomes very similar to the infants who were appropriate for gestational age and very different prognoses than the asymmetrically SGA fetuses, thus reinforcing the concept of using growth parameters for diagnostic and outcome counseling.

Several studies have addressed prognostic factors influencing outcome and have consistently reported that the dominant influence on survival is gestational age at birth. Madazli reported experience with fetuses with FGR with absent end-diastolic flow. No fetus of less than 28 weeks' gestation and less than 800 g survived. Madazli also noted that all fetuses with absent end-diastolic flow of greater than 31 weeks' gestation survived. The variable period for survival occurred between these gestational ages, with antenatal and neonatal survival rates at 28-31 weeks' gestation of approximately 54%. [6]

The stress that results in FGR has been postulated to also cause advanced maturation of the fetus, resulting in decreased perinatal morbidity compared with age-matched normally grown neonates. Bernstein et al examined this issue by identifying almost 20,000 white or African American neonates from 196 centers who were born at 25-30 weeks' gestation without major anomalies. [7] They categorized infants as having FGR at less than the 10th percentile using race- and sex-specific growth charts. These results do not support the concept of a stress-related protective effect of FGR.

Relative risks associated with FGR using morbidity and mortality parameters, from the study by Bernstein et al, are as follows:

-

Relative risk of death, 2.77; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.31-3.33

-

Relative risk of respiratory distress syndrome, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.03-1.29

-

Relative risk of intraventricular hemorrhage, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.99-1.29

-

Relative risk of severe intravascular hemorrhage, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.98-1.59

-

Relative risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53

Increasingly, data support the idea that long-term consequences of FGR last well into adulthood. Several authors have noted that these individuals have a greater predisposition to develop a metabolic syndrome later in life, manifesting as obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this relationship. Hales and Barker proposed the so-called thrifty phenotype in 1992. This idea suggests that intrauterine malnutrition results in insulin resistance, loss of pancreatic beta-cell mass, and an adult predisposition to type 2 diabetes.

Other authors found that prepubertal individuals who had FGR at birth show a greater insulin response than prepubertal individuals who had healthy growth as infants. This suggests that the increased risk of type 2 diabetes in adults who had restriction as infants stems, instead, from increased peripheral insulin resistance that allows the brain-sparing physiology to occur but with a permanent reduction in skeletal-muscle glucose transport. This ultimately results in beta-cell burnout. Although the causative pathophysiology is uncertain, the risk of a metabolic syndrome in adulthood is clearly increased among individuals who had FGR at birth.

Organ system–specific morbidity, as a result of growth restriction, is now being evaluated using different animal species and models. Human studies have clearly shown organ-specific sequelae of FGR. Kaijser et al, using a large cohort, were able to demonstrate an association between low birth weight and adult risk of ischemic heart disease. [8] Hallan et al demonstrated that adult kidney function is adversely affected by restricted intrauterine growth. [9]

In addition to an increased risk of physical sequelae, mental health problems have been found more commonly in children with growth restriction. In a study performed in Western Australia, Zubrick et al showed that children born below the second percentile for weight were at significant risk for mental health morbidity (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.18-7.12), academic impairment (odds ratio, 6; 95% Cl, 2.25-16.06), and poorer general health (odds ratio, 5.1; 95% Cl, 1.69-15.52). [10] Specifically, Tideman et al have shown that impaired fetal circulation, as demonstrated by Doppler studies, in association with FGR, results in worsened cognitive function in adulthood. [11]

Diagnosis and Surveillance

Criteria for diagnosis of FGR

For most purposes, an EFW at or below the 10th percentile is used to identify fetuses at risk. According to the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, the recommended definition of FGR is a sonographic EFW or abdominal circumference (AC) below the 10th percentile for gestational age. [12] Importantly, however, understand that this is not a definitive cutoff for uteroplacental insufficiency. A certain number of fetuses at or below the 10th percentile may be constitutionally small. In these cases, short maternal or paternal height, the neonate's ability to maintain growth along a standardized curve, and a lack of other signs of uteroplacental insufficiency (eg, oligohydramnios, abnormal Doppler findings) can be reassuring to the clinician and parents. Customized growth curves for ethnicity, parental size, and gender are in development so as to improve sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing FGR. [13, 14] It is recommended that population-based fetal growth references be used in determining fetal weight percentiles (ie, Hadlock). [12]

Importantly, review the dating criteria before offering intervention to treat growth restriction in a fetus. If dates are uncertain or unknown, obtaining a second growth assessment over a 2- to 4-week interval may be of value unless strong supportive data or risk factors warrant an immediate change in management plans.

Screening the fetus for growth restriction

Although no single biometric or Doppler measurement is completely accurate for helping make or exclude the diagnosis of growth restriction, screening for FGR is important to identify at-risk fetuses. Dependent upon the maternal condition associated with FGR (see Maternal causes of FGR), patients may undergo serial sonography during their pregnancies. An initial scan may be obtained in the middle of the second trimester (at 18-20 weeks) to confirm dates, evaluate for anomalies, and identify multiple gestations. A repeat scan may be scheduled at 28-32 weeks' gestation to assess fetal growth, evidence of asymmetry, and stigmata of brain-sparing physiology (eg, oligohydramnios, abnormal Doppler findings).

Screening for FGR in the general population relies on symphysis–fundal height measurements. This is a routine portion of prenatal care from 20 weeks' gestation until term. Although recent studies have questioned the accuracy of fundal height measurements, particularly in obese patients, a discrepancy of greater than 3 cm between observed and expected measurements may prompt a growth evaluation using ultrasound. [15] The clinician should be aware that the sensitivity of fundal height measurement is limited, and he or she should maintain a heightened awareness for potential growth-restricted fetuses. In an unselected hospital population, only 26% of fetuses that were SGA were suggested to be SGA based on clinical examination findings.

One study using fundal height curves that customized for maternal weight, height, and ethnicity was able to increase the detection rate from 29.2% in the control group to 47.9% in the study population. As Yoshida et al indicated, these inaccuracies occur (1) because of the limited accuracy of predicting birth weight within 10% using ultrasonography in the third trimester, (2) because not all fetuses that are SGA have FGR, (3) because individual and unpredictable changes in growth potential occur, and (4) because growth distribution is a continuum. [16]

Biometry and amniotic fluid volumes

Most ultrasonographic machines report aggregate gestational age measurements and individual parameters. Assessing individual values is important to identify a fetus that is growing asymmetrically. In the presence of normal head and femur measurements, abdominal circumference (AC) measurements of less than 2 standard deviations below the mean appear to be a reasonable cutoff to consider a fetus asymmetric. Baschat and Weiner showed that a low AC percentile had the highest sensitivity (98.1%) for diagnosing FGR (birth weight < 10th percentile). The sensitivity of EFW (birth weight below the 10th percentile) is 85.7%; however, an AC below the 2.5 percentile had the lowest positive predictive value (36.3%), while a low EFW had a 50% positive predictive value. [17]

Supporting evidence of a hostile intrauterine environment can be obtained by specifically looking at amniotic fluid volumes (AFVs). Chauhan et al found that in a group of normal pregnancies greater than 24 weeks', the rate of FGR was 19% with an amniotic fluid index (AFI) of less than 5 and 9% with an AFI higher than 5 (odds ratio, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.10-4.16). [18] Banks and Miller also noted a significantly increased risk of FGR in a group of fetuses with borderline amniotic fluid (AFI of 5-10) relative to a group of normal fetuses (AFI >10) (13% vs 3.6%; rate ratio, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.2-16.2). [19] These results confirm much earlier work by Chamberlain et al. [20]

These authors showed an increased rate of FGR among fetuses with decreasing maximum vertical pocket (MVP) values. An MVP measurement of larger than 2 cm was associated with an FGR rate of 5%, an MVP value smaller than 2 cm was associated with a FGR rate of 20%, and an MVP measurement of smaller than 1 cm was associated with an FGR rate of 39%. Chamberlain et al concluded that decreased AFI may be an early marker of declining placental function. [20]

Uterine artery Doppler measurement

Both arterial Doppler and venous Doppler have been used to support expectant management or delivery of fetuses with FGR and to identify fetuses at risk. Doppler velocimetry has been shown to contribute to the identification of fetuses at risk for FGR. To follow is an overview of the various Doppler techniques and their clinical applications.

Flow patterns of maternal uterine arteries have been shown to reflect the impact of placentation on maternal circulation. Albaiges et al suggest that a one-stage uterine artery screening at 23 weeks' gestation is effective in identifying pregnancies that will have poor perinatal outcomes prior to 34 weeks' gestation related to uteroplacental insufficiency. In their study of 1751 women who were seen at 23 weeks' gestation for any reason, an abnormal uterine artery study result included bilateral uterine artery notches or a mean pulsatility index (PI) of greater than 1.45 in both arteries. [21]

These criteria were observed in approximately 7% of the population. Within this 7% were 90% of the women who later developed preeclampsia and required delivery before 34 weeks' gestation, 70% of women with a fetus below the 10th percentile who required delivery before 34 weeks' gestation, 50% of placental abruptions, and 80% of fetal deaths. Importantly, the negative predictive value for these adverse events prior to 34 weeks' gestation was higher than 99%.

Chien et al conducted an overview of published studies on the efficacy of uterine artery Doppler findings as a predictor of preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and perinatal death. [22] In reports of studies performed on low-risk women, an abnormal uterine artery Doppler result yielded a likelihood ratio (LR) of developing IUGR of 3.6 (95% CI, 3.2-4), while a normal test result reduced the risk to below background, with an LR of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.08-0.09). For women at high risk, an abnormal test result indicated an LR of 2.7 (95% CI, 2.1-3.4), while a normal result reduced the risks by 30% (LR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6-0.9).

Although these measurements appear promising, the sensitivity and specificity of uterine artery Doppler measurements are relatively low, and, because no proven interventions are available to prevent FGR, uterine artery blood flow measurements are not included in routine surveillance protocols.

Umbilical artery Doppler measurement

In normal pregnancies, umbilical artery (UA) resistance shows a continuous decline; however, this may not occur in fetuses with uteroplacental insufficiency. The most commonly used measure of gestational age–specific UA resistance is the systolic-to-diastolic ratio of flow, which changes from a baseline value to an elevated value with worsening disease. As the insufficiency progresses, end-diastolic velocity is lost and, finally, reversed. The clinical significance of this progression has been well documented by Mandruzzato et al, who reported a significant difference in mean birth weight and perinatal mortality for absent end-diastolic velocity (20%) versus reversed end-diastolic velocity (68%). [23]

The status of UA blood flow corroborates the diagnosis of FGR and provides early evidence of circulatory abnormalities in the fetus, enabling clinicians to identify the high-risk status of these fetuses and to initiate surveillance (see Management and Delivery Planning).

UA Doppler measurements may help the clinician decide whether a small fetus is truly growth restricted.

Baschat and Weiner looked at UA resistance to determine if it can help improve the accuracy of diagnosing FGR and help identify a small fetus at risk for chronic hypoxemia. These investigators identified 308 babies of greater than 23 weeks' gestation at the time of delivery who had an AC of less than the 2.5 percentile, an EFW of less than the 10th percentile, or both criteria. UA measurements were obtained on all of these fetuses. The positive predictive values of AC alone and EFW alone for the diagnosis of FGR were 36.6% and 50%, respectively. An elevated UA systolic-to-diastolic ratio yielded a positive predictive value of 53.3% for postnatally confirmed FGR.

Among all 138 identified fetuses with an elevated UA systolic-to-diastolic ratio, a 10-fold increase occurred in the rate of admission to and the duration of stay in neonatal intensive care units (ICUs) and in the frequency and severity of respiratory distress syndrome. Equally importantly, no fetus with normal Doppler measurements was delivered with documented metabolic acidemia. [17]

Middle cerebral artery Doppler

Fong et al identified 297 singleton pregnancies in which EFW was below the 10th percentile in anatomically normal fetuses. These investigators studied middle cerebral artery (MCA), renal artery, and UA Doppler findings. They addressed outcomes, including cesarean delivery for fetal distress, cord pH less than or equal to 7.10, and Apgar score less than or equal to 7 at 5 minutes. They concluded that a normal MCA Doppler finding may be useful to help identify small fetuses that are not likely to have a major adverse outcome with a reported negative predictive value of 86%. [24]

Hershkovitz et al also looked at MCA Doppler finds in small fetuses. They found that those fetuses with abnormal MCA study results had earlier deliveries, lower birth weights, fewer vaginal deliveries, and increased admissions to neonatal ICUs. Importantly, only 7 of 16 fetuses with Doppler evidence of brain-sparing physiology had elevated UA Doppler findings. This emphasized the possible presence of a gradient in the degree of fetal redistribution and that when performing Doppler studies, evaluating only the UAs may not be sufficient. [25]

Specific MCA Doppler changes were evaluated by Mari et al. They specifically evaluated MCA peak systolic velocity (PSV) and pulsatility index (PI) in growth-restricted fetuses that were longitudinally evaluated. They found that while an abnormal PI preceded an abnormal PSV, the PI demonstrated an inconsistent pattern. MCA-PSV, however, consistently showed an increase in blood velocity and immediately prior to demise, a decrease. They concluded that MCA-PSV is a better predictor of FGR-associated perinatal mortality than any other single measurement. [26]

Venous Doppler waveforms

Venous Doppler has been measured at the ductus venosus (DV), umbilical vein (UV), inferior vena cava (IVC), and 7 other sites. This provides information about fetal cardiovascular and respiratory responses to the intrauterine environment. These measurements have been reported to become consistently abnormal when a fetus is severely compromised, thus providing evidence in support of an expedited delivery. Bilardo et al completed a prospective study of the cardiotocography, UA, and DV values of 70 fetuses with FGR and their outcomes. [27] They reported that only the DV measurements consistently predicted adverse perinatal outcomes from 0-7 days prior to delivery. While the optimal vessel for use for venous Doppler evaluations has not been identified, the knowledge gained from these measurements may provide additional information for the timing of delivery, especially in extremely premature (< 32 wk) gestations.

Three-dimensional ultrasonography

Obstetrical 3-dimensional ultrasonography has been used to evaluate the growth-restricted fetus. As fetal femur dysplasia is associated with FGR, Chang et al used 3-dimensional ultrasonography to measure fetal femur volume as a predictor of FGR. They found a 10th percentile femur volume threshold, which differentiates growth-restricted fetuses from normal fetuses. Using this technique, they obtained a sensitivity of 71.4%, specificity of 94.1%, positive predictive value of 62.5%, negative predictive value of 96.0%, and accuracy of 91.3% in the prediction of growth restriction. As a single biometric measurement, fetal femur volume is better in the prediction of growth restriction than fetal AC and biparietal diameter. [28]

Chang et al also evaluated 3-dimensional ultrasonographic measurement of fetal humerus volume in the assessment of FGR. Again, a 10th percentile humerus volume threshold was found to differentiate growth-restricted fetuses from normal fetuses. [29]

Therapeutic options

Although multiple therapeutic strategies have been tested to promote intrauterine growth and decrease perinatal morbidity and mortality, limited, if any, success has been achieved in this area. Gülmezoglu et al reported results of meta-analyses of studies, the goals of which were to treat impaired growth. In this review, the following 3 interventions were shown to be helpful [30] :

-

First, behavioral strategies to quit smoking result in a lower rate of low birth weight in babies at term among mothers who smoke.

-

Second, balanced nutritional supplements in undernourished women and magnesium and folate supplementation (in some studies) decrease the rate of SGA newborns.

-

Third, if malaria is the etiologic agent, maternal treatment of malaria can increase fetal growth.

Additionally, Pollack et al examined in-hospital bed rest as a way to promote fetal growth and found no improvement. [31] Newnham et al studied women receiving 100 mg of aspirin versus placebo after a diagnosis of FGR based on abnormal UA Doppler findings, and they did not find a clinically significant difference. [32]

Other options have been considered with a goal of decreasing perinatal morbidity and mortality. Say et al reviewed maternal estrogen administration, maternal hyperoxygenation, and maternal nutrient supplementation as therapies for suspected impaired fetal growth. [33, 34, 35] They concluded that evidence to evaluate the risks and benefits of these therapies was lacking. However, they did suggest that further trials of maternal hyperoxygenation seem warranted.

Additional therapies that have been proposed and may warrant further study are maternal hemodilution and intermittent abdominal negative pressure. These are also poorly studied, carry potential maternal and fetal harm, and should be considered experimental.

The only intervention that has been shown to decrease neonatal morbidity and mortality is the administration of steroids to premature fetuses when delivery is anticipated. Bernstein et al described the effect of maternal prenatal glucocorticoid administration in growth-restricted fetuses and found the benefits to be similar to those found in gestational age–matched, normally grown fetuses.

Odds ratio reduction with steroids, from Bernstein et al, is as follows [7] :

-

Relative risk of death, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.48-0.62

-

Relative risk of respiratory distress syndrome, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.44-0.58

-

Relative risk of intraventricular hemorrhage, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.61-0.73

-

Relative risk of severe intravascular hemorrhage, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.43-0.57

-

Relative risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, no difference noted

Several studies have questioned the metabolic and cardiovascular response of fetuses with FGR to maternal glucocorticoid administration. Simchen et al performed a prospective longitudinal study of chromosomally normal fetuses with FGR at 24-34 weeks' gestation with absent or reversed end-diastolic flow. They found a divergent response between the 2 groups of fetuses as measured by UA Doppler. Almost 45% of these fetuses had transient improvement in their Doppler waveforms, and these fetuses had significantly better outcomes than their counterparts who had no improvement of their waveforms, even transiently.

These authors suggest that daily Doppler-based monitoring after the administration of steroids can help delineate a group of fetuses at extremely high risk for acidosis and mortality. They also suggest that further work is needed to elucidate the efficacy of steroids versus immediate delivery in this very high-risk subset of fetuses with FGR. [36]

Management and Delivery Planning

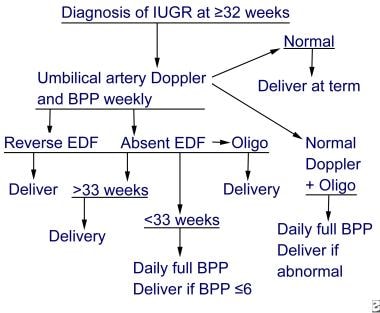

Once FGR has been detected, the management of the pregnancy should depend on a surveillance plan that maximizes gestational age while minimizing the risks of neonatal morbidity and mortality. This should include corticosteroid administration when at all feasible, based on the monitoring and delivery strategies discussed below (see image below and Harman and Baschat's integrated fetal testing for FGR).

To improve neonatal outcomes, antenatal corticosteroids should be administered if delivery will likely occur before 33 6/7 weeks of gestation. If delivery is expected within 7 days and a patient has not received a prior course, antenatal corticosteroids should be administered between 34 0/7 weeks and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation as well. Neuroprotection via the administration of magnesium sulfate is also recommended for deliveries prior to 32 weeks. [37]

The goal in the management of FGR, because no effective treatments are known, is to deliver the most mature fetus in the best physiological condition possible while minimizing the risk to the mother. Such a goal requires the use of antenatal testing with the hope of identifying the fetus with FGR before it becomes acidotic. Developing a testing scheme, following it, and having a high index of suspicion in this population when results of testing are abnormal are important. The positive predictive value of an abnormal antenatal test result in fetuses with FGR is relatively high because the prevalence of acidemia and chronic hypoxemia is relatively high.

Although numerous protocols have been suggested for antenatal monitoring of fetuses with FGR, the mainstay includes a nonstress test (NST). Additional modalities may include amniotic fluid volume determination, biophysical profiles, and/or Doppler assessments.

Other more complex protocols have been proposed. The protocol for antenatal testing suggested by Kramer and Weiner (see image below) is one example. [38] It relies heavily on the use of UA Doppler testing because severely abnormal Doppler findings (absent or reversed end-diastolic flow) can precede an abnormal fetal heart rate by several weeks.

Fetal growth restriction. Sample protocol for antenatal testing for intrauterine growth restriction at 32 weeks' gestation or after. IUGR is intrauterine growth restriction, BPP is biophysical profile, and EDF is end-diastolic flow.

Fetal growth restriction. Sample protocol for antenatal testing for intrauterine growth restriction at 32 weeks' gestation or after. IUGR is intrauterine growth restriction, BPP is biophysical profile, and EDF is end-diastolic flow.

Harman and Baschat proposed a different antenatal testing strategy. This protocol integrates multiple venous and arterial Doppler measurements and the biophysical profile score (BPS); this strategy may be used at institutions where these measurements are routinely obtained by qualified technicians. [39]

Harman and Baschat's integrated fetal testing for FGR, in increasing order of severity from 1 (least severe) to 5 (most severe), is as follows [39] :

Situation 1

See the list below:

-

Test results – AC less than fifth percentile, low AC growth rate, high ratio of head circumference to AC; BPS greater than or equal to 8 and AFV normal; abnormal UV and/or cerebroplacental ratio; normal MCA.

-

Interpretation – FGR diagnosed, asphyxia extremely rare, increased risk of intrapartum distress.

-

Recommended management – Intervention for obstetric or maternal factors only, weekly BPS, multivessel Doppler every 2 weeks.

Situation 2

See the list below:

-

Test results – FGR criteria met, BPS greater than or equal to 8, AFV normal, UA with absent or reversed end-diastolic velocities, decreased MCA.

-

Interpretation – FGR with brain sparing, hypoxemia possible and asphyxia rare, at risk for intrapartum distress.

-

Recommended management – Intervention for obstetric or maternal factors only; BPS 3 times a week; weekly UA, MCA, and venous Doppler.

Situation 3

See the list below:

-

Test results – FGR with low MCA PI; oligohydramnios; BPS greater than or equal to 6; normal IVC, DV, and UV flow.

-

Interpretation – FGR with significant brain sparing, onset of fetal compromise, hypoxemia common, acidemia/asphyxia possible.

-

Recommended management – If at more than 34 weeks' gestation, deliver (route determined by obstetric factors). If at less than 34 weeks' gestation, administer steroids to achieve lung maturity and repeat all testing in 24 hours.

Situation 4

See the list below:

-

Test results – FGR with brain sparing, oligohydramnios, BPS greater than or equal to 6, increased IVC and DV indices, UV flow normal.

-

Interpretation – FGR with brain sparing, proven fetal compromise, hypoxemia common, acidemia/asphyxia likely.

-

Recommended management – If at more than 34 weeks' gestation, deliver (route determined by obstetric factors and oxytocin challenge test [OCT] results). If at less than 34 weeks' gestation, individualize treatment with admission, continuous cardiotocography, steroids, maternal oxygen, and/or amnioinfusion and then repeat all testing up to 3 times a day depending on status.

Situation 5

See the list below:

-

Test results – FGR with accelerating compromise, BPS less than or equal to 6, abnormal IVC and DV indices, pulsatile UV flow

-

Interpretation – FGR with decompensation, cardiovascular instability, hypoxemia certain, acidemia/asphyxia common, high perinatal mortality, death imminent

-

Recommended management – If fetus is considered viable by size, deliver as soon as possible at tertiary center. Route determined by obstetric factors and OCT results. Fetus requires highest level of neonatal ICU care.

The diagnosis of severe FGR before 32 weeks' gestation is associated with a poor prognosis, and therapy must be highly individualized. Once a decision has been made to effect delivery, the mode of delivery is governed by evidence of acidemia, gestational age, and Bishop score. Cesarean delivery without a trial of labor may be appropriate (1) in the presence of evidence of fetal distress by nonstress testing or reversed diastolic flow or (2) for traditional obstetrical indications for cesarean delivery (ie, malpresentation, prior cesarean delivery).

A joint conference of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists established recommended timing of delivery of growth-restricted fetuses. These recommendations are based on the following 2 clinical scenarios [37] :

-

The first group, fetuses with uncomplicated (isolated) fetal growth restriction, should be delivered between 38 0/7 weeks and 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

-

The second group, fetuses with complicated fetal growth restriction, which includes oligohydramnios, abnormal UA Doppler velocimetry results, and maternal risk factors or comorbidities, should be delivered at 32 0/7 weeks to 37 6/7 weeks of gestation.

A population-based cohort study by Monier et al that investigated the impact of gestational age at diagnosis of FGR on rates of live birth and survival reported fetal growth restriction before 28 weeks in 436 of 3698 fetuses (11.8%) of which 66.9% were live born and 54.4% survived to discharge. When diagnosis occurred before 25 weeks, 50% were live born, 66% at 25 weeks and >90% at 26 and 27 weeks. [40]

Li et al investigated the success rate of induction of labor in FGR fetuses with and without UA blood flow changes and the neonatal outcomes of induced fetuses with a negative result after an OCT. They found that fetuses with abnormal (but not absent or reversed) UA blood flow who had a normal OCT result had similar success in induction of labor, without indications of detrimental fetal hypoxia or distress. [41] This suggests that in fetuses with altered UA blood flow, an OCT may be appropriate to select fetuses that will tolerate labor induction.

When a trial of labor is undertaken, continuous heart rate monitoring should optimize the success of the induction.

Future Directions and Prevention

Prevention of FGR is highly desirable, and several studies have addressed this potential. Investigators have looked at altering the thromboxane-to-prostacyclin ratio by administering aspirin with or without dipyridamole to mothers of fetuses with FGR. The studies examining these agents for prevention of FGR are difficult to compare. Different doses of aspirin, different times of administration in pregnancy, and different indications for use make comparisons difficult; however, the following is a summary of the studies:

-

Wallenburg et al studied a population of women at high risk for FGR in a nonrandomized trial using historic controls. They noted a decline in the rate of FGR from 61.5% in the historic controls to 13.3% in those treated with aspirin and dipyridamole. [42]

-

Sibai et al studied low-risk nulliparous women in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Patients were treated from weeks 13-26 with either placebo or 60 mg/d of aspirin. This study showed a small decrease in the rate of preeclampsia but not FGR (4.6% vs 5.8% in controls), at the risk of increased chance of abruption. [43]

-

In the Essai Preeclampsia Dipyridamole Aspirine (EPREDA) randomized controlled trial, high-risk patients received placebo, aspirin only, or aspirin plus dipyridamole. No difference in the rate of FGR was found between those receiving aspirin alone and those receiving aspirin plus dipyridamole. The control rate of FGR was 26%; in the 2 groups receiving aspirin with or without dipyridamole, the rate was 13%. [44]

-

In an Italian study, women considered to be at moderate risk for FGR or pregnancy-induced hypertension at 16-32 weeks' gestation were randomly assigned to receive either 50 mg of aspirin or no treatment. No difference in any outcome studied was found between the 2 groups. [45]

-

Harrington et al identified patients with abnormal uterine artery Doppler findings at 20 weeks' gestation. Participants were started on aspirin, and therapy was discontinued at 24 weeks' if repeat Doppler results normalized. No difference in the rate of fetuses that were SGA below the 10th or third percentile was found between the treated and control groups. [46]

-

Trudinger et al performed a double-blinded, randomized clinical trial using 150 mg of aspirin in pregnant women with abnormal UA Doppler findings. The result was an increase in birth weight of 516 g and an increase in placental weight. [47]

-

The Collaborative Low-Dose Aspirin Study in Pregnancy trial, which investigated both prevention and treatment of FGR, showed no change in the rate of FGR in treated and control patients with the administration of 60 mg of aspirin. [48]

-

Leitich et al performed a meta-analysis of 13 trials in which women were enrolled for prophylactic aspirin therapy. In women treated, the odds ratio for FGR was 0.82 (95% Cl, 0.66-1.08). Among those trials in which women were hypertensive or had other risk factors, the risk of FGR was clearly decreased. Leitich et al found that beginning 100-150 mg/d of aspirin at less than 17 weeks' gestation decreased the rate of FGR by approximately 65% and the rate of perinatal mortality by approximately 60%. [49]

-

The Disproportionate Intrauterine Growth Intervention Trial At Term (DIGITAT) suggests that women who have had a previous singleton pregnancy beyond 36 weeks’ gestation can safely choose expectant management with intensive maternal and fetal monitoring if induction is not wanted. [50] Choosing induction to prevent neonatal morbidity or stillbirth is reasonable.

Despite the theoretical benefit of aspirin in many studies, the role of aspirin, if any, in the prevention of FGR is still unclear. A large randomized controlled trial using a standardized high-risk population with a standardized treatment regimen could serve to better answer this question.

Conclusion

FGR remains a challenging problem for clinicians. Most cases of FGR occur in pregnancies in which no risk factors are present; therefore, the clinician must be alert to the possibility of a growth disturbance in all pregnancies. No single measurement helps secure the diagnosis; thus, a complex strategy for diagnosis and assessment is necessary. The ability to diagnose the disorder and understand its pathophysiology still outpaces the ability to prevent or treat its complications. The current therapeutic goals are to optimize the timing of delivery to minimize hypoxemia and maximize gestational age and maternal outcome. Further study may elucidate preventive or treatment strategies to assist the growth-restricted fetus.

-

Fetal growth restriction. Distribution of small fetuses.

-

Fetal growth restriction. Sample protocol for antenatal testing for intrauterine growth restriction at 32 weeks' gestation or after. IUGR is intrauterine growth restriction, BPP is biophysical profile, and EDF is end-diastolic flow.