Overview

Vaginal/urethral sling is a procedure used to manage stress urinary incontinence (SUI), which is an underdiagnosed and underreported medical problem. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) affects 15-60% of women. SUI is a disorder that affects both young and elderly individuals. For example, more than one-fourth of nulliparous young college athletes experience SUI when participating in sports.

Because of social stigma, an estimated 50-70% of women with urinary incontinence fail to seek medical evaluation and treatment. Of individuals with urinary incontinence, only 5% in the general community and 2% in nursing homes receive appropriate medical evaluation and treatment. Patients with urinary incontinence often endure this condition for 6-9 years before seeking medical therapy.

Historically, female SUI was broadly subcategorized into types I, II, and III, as follows:

-

Type I SUI is defined as urine loss occurring in the absence of significant urethral hypermobility or intrinsic sphincter deficiency. This is the mildest form of SUI.

-

Type II SUI is defined as urine loss occurring due to urethral hypermobility. This is also known as genuine stress urinary incontinence (GSUI).

-

Type III SUI is defined as urine leakage occurring from an intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD). ISD is a more complex form of female SUI.

The subcategories of female SUI can be ascertained by direct physical examination and by measuring an abdominal leak point pressure (ALPP). ALPP, also known as the Valsalva or stress leak point pressure, [7, 8] is defined as the lowest abdominal pressure necessary to cause urine leakage.

Absolutely cut-offs vary, but traditionally, an ALPP less than 60 cm water is considered diagnostic of type III SUI, whereas an ALPP of 90-120 cm water is consistent with type II SUI. Values of 60-90 cm water reflect the presence of both type II and type III, in combination. An ALPP greater than 120 cm water is considered diagnostic of type I SUI.

Recent experience suggests that leak point pressures need not be stratified as they were in the past, as slings manage all types of SUI. The types of incontinence just listed are noted for descriptive and historical purposes only. [9] Once thought to be two separate components, urethral hypermobility and ISD are now recognized as two points on a continuum. [10]

Go to Nonsurgical Treatment of Urinary Incontinence and Surgical Treatment of Urinary Incontinence for complete information on these topics.

Sling procedures

Slings have excellent overall success and durable cure rates (see the image below). The sling augments the resting urethral closure pressure with increases in intra-abdominal pressure that happen with "stress maneuvers" such as coughing, sneezing, and laughing.

Several sling options have been described and are used in current practice, including autologous fascial slings and mid-urethral synthetic mesh sling. Whatever sling surgery is performed, one should use the technique that produces the best outcomes in the hands of that particular surgeon.

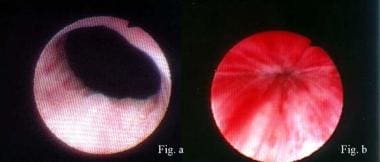

Lead-pipe urethra (Figure a) converted to normal urethra with excellent mucosal coaptation (Figure b) by means of proper sling surgery. Surgery cured this patient of stress urinary incontinence.

Lead-pipe urethra (Figure a) converted to normal urethra with excellent mucosal coaptation (Figure b) by means of proper sling surgery. Surgery cured this patient of stress urinary incontinence.

Autologous Pubovaginal Fascial Sling

Von Giordano is usually credited with performing the first pubovaginal sling operation in 1907, using a gracilis muscle graft around the urethra. In 1910, Goebel described treating SUI by rotating the pyramidalis muscles such that their insertion to the pubic bone was conserved, but the ends were joined together below the bladder neck and urethra. [11] In 1914, Frangenheim modified the Goebel’s procedure by incorporating the aponeurosis of the abdominal rectus muscles into the sling of the pyramidalis muscles. [12] Adopting these earlier techniques, McGuire was the first to describe a modern version of the pubovaginal sling (PVS) in the 1970s, using a strip of rectus fascia that remained attached laterally on one side. [13] The contemporary technique of harvesting a free graft from the rectus fascia, developed by Blavias and Jacobs in 1991 allowed for the ability to tension the PVS. [14]

Historically, surgeons have used the rectus fascia or fascial lata pubovaginal sling for the treatment of ISD, complex SUI, or after a failed anti-incontinence operation. There has been a recent increase in the use of the autologous sling given the Food and Drug Administration's Public Health Notification regarding the use of transvaginal mesh for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. [15]

Mid-Urethral Slings

Based on the "Hammock theory" of stress urinary incontinence, in which the pubocervical fascia provides hammock-like support for the bladder neck and thereby creates a backboard for compression of the proximal urethra during increased intra-abdominal pressure, a new type of sling to treat SUI emerged. [16] The tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) was developed in Europe in the 1990s. The TVT is a polypropylene-meshed tape that is placed at the mid-urethra. [17] With the introduction of the TVT, it became the most common anti-incontinence procedure first in Europe and then in the United States. [18]

The TVT is placed using a retropubic approach, in which two needles are placed behind the pubic bone, travel through the space of Retzius, and exit through an incision in the anterior vaginal wall. Since the introduction of the TVT, several modifications have been made to the surgical approach. The transobturator tape (TOT) was developed to decrease the risk of bladder injury. More recently, is the development of the single-incision sling (SIS), or "mini-sling" in which the mesh is anchored to the endopelvic fascia (with a retropubic approach) or the obturator membrane and muscles (with a transobturator approach).

Indications

The indications for sling surgery in women are bothersome SUI that affects the quality of life and potential incontinence in a patient undergoing prolapse repair. When conservative treatment measures, including diet modification, pelvic floor exercises, smoking cessation, and weight loss, have failed, the sling can be considered.

Contraindications

A clear contraindication to sling surgery is pure urge incontinence or mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) in which urge is the predominant component. An inherent risk of any sling procedure is de novo or worsening urge symptoms, Thus, surgeons must identify and treat the presence of an urge component before surgery.

Conversely, poor detrusor function is a relative contraindication to sling surgery because the potential for urinary retention is increased. Women with absent or poor detrusor function in the presence of SUI are at a higher risk of experiencing prolonged postoperative urinary retention.

Patient Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation

The American Urological Association (AUA), in conjunction with the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine, and Urogenital Reconstructive Surgery (SUFU), has published guidelines regarding the standard evaluation and treatment of female SUI. [19] In the initial evaluation of a patient with SUI who wishes to have a surgical procedure such as a sling, the physician should perform a thorough history (including eliciting how bothered the patient is by the SUI), a pelvic exam with a demonstration of SUI, a post-void residual, and a urinalysis. [19] Additional testing such as urodynamics and cystoscopy can be performed in patients with a significant complaint of urgency urinary incontinence, significant pelvic organ prolapse (Stage 3 or higher), elevated post-void residual, suspected neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction, prior anti-incontinence surgery, or prior prolapse surgery. [19]

Preparation

Preoperative counseling

Counseling should address potential risks and complications (eg, bleeding, infection, persistent SUI, de novo urge incontinence, worsening urge incontinence, urinary retention). Complications unique to synthetic slings are sling infection, erosion of the mesh into the urethra, or vaginal extrusion of the mesh. All patients undergoing sling surgery should be informed of the possible need for postoperative self-catheterization and short- and longer-term voiding dysfunction.

Preoperative planning

All patients should have preoperative sterile urine culture. Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics are administered one hour before skin incision.

Anesthesia

Generally, for sling procedures, the patient is completely anesthetized. However, there have been reports of surgeons placing slings under local anesthesia. [20]

Equipment

Surgeons may use a number of materials for constructing slings: autologous tissues, allogenic grafts, and synthetic mesh materials.

Autologous tissue

Autologous tissue used for sling procedures includes rectus fascia or fascia lata. Surgeons harvest autologous sling materials at the time of sling surgery. In a standard pubovaginal sling procedure, typically a 10 cm x 2 cm strip of fascia is harvested, but a segment as short as 5-6 cm x 1 cm can be used.

Allogenic grafts

Allogenic grafts include cadaveric fascia lata and rectus fascia that have been processed by freeze-drying, gamma irradiation, or solvent dehydration. These tissues are harvested from cadaver donors and must be rehydrated at the time of sling surgery.

The advantages of allografts include shorter operating times and decreased morbidity. However, it has been shown that the processing of allograft cadaveric tissue may compromise the integrity of the graft and may be associated with a higher long-term failure rate. The specific processing technique can also make a difference in the tissue's integrity. Tissue freezing leads to ice crystal formation that can lead to disruption of the collagen matrix, which weakens the tissue. [21] Reported failure rates for frozen or freeze-dried grafts range from 6.0% to 38%. [22] For this reason, solvent-dehydrated allograft has predominated.

The literature is mixed regarding the outcomes of pubovaginal sling with autologous fascia versus cadaveric allograft fascia. Some researchers have reported equally high success rates and no difference in complications, concluding that allograft may be used to reduce operative time and morbidity. [23, 24] Other authors have shown that allograft may be associated with inferior outcomes, recurrent symptoms, and a higher re-operative rate. [25, 26, 27, 28]

Synthetic mid-urethral sling materials

The benefits of synthetic materials are decreased operating time, less morbidity (ie, no need for large suprapubic incision), and the potential for better long-term durability. Potential risks of synthetic slings include vaginal and urethral tissue erosion. [29] Synthetic slings are permanent polypropylene mesh. Current synthetic mesh slings are considered "Type I" mesh, which is defined as macroporous with pores of greater than 75 microns, allowing for macrophages, fibroblasts, blood vessels, and collagen to enter the mesh. [30] The matrix of the polypropylene sling allows it to become incorporated into the host tissue, with minimal bacterial colonization and decreased erosion.

The synthetic mid-urethral sling is considered safe and effective by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has not been recalled. The full-length knitted polypropylene mid-urethral sling has been reviewed by the FDA and found to be safe and effective. With over 2,000 articles published on the use of mid-urethral sling, it is the most studied surgery to treat SUI. Two large government-funded studies have evaluated the mid-urethral sling’s safety and efficacy – both found the procedure to have a low complication rate and a high success rate. Other large scientific studies from around the world have supported the safety and efficacy of the mid-urethral sling. [31]

Surgical Technique

Positioning

The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position for the duration of the procedure. The patient’s vagina and abdomen as far cephalad as the umbilicus are prepped. If fascia lata is to be harvested, the lower extremity of interest is internally rotated at the hip while in lithotomy or may be harvested from the supine position prior to placement of the patient into the lithotomy position. The anterolateral aspect of the patient’s thigh is prepped and draped from the greater trochanter to the distal patella.

Pubovaginal autologous and allograft slings

Graft harvest

The desired graft material will be selected prior to the procedure. If allograft material is to be used, it should be available and opened at the appropriate step of the case.

Rectus fascia has historically been the more commonly utilized autologous graft and is harvested with the patient in the lithotomy position. A transverse lower abdominal incision (Pfannenstiel) over the suprapubic area is made with dissection down to the level of the rectus fascia. The fascia is cleared so that the graft of the desired length can be harvested; once the graft of the desired length is obtained it is placed on the back table for later use. The rectus fascia can either be closed at this time or after the passage of the sutures through the retropubic space.

Fascia lata grafts can be harvested in the lithotomy or supine position. For supine harvest, the patient's hip is bumped up, and the superior leg is slightly flexed. The outer thigh is prepped and draped using a sterile technique. For lithotomy harvest, the lower extremity of interest is internally rotated at the hip. The anterolateral aspect of the patient’s thigh is prepped and draped from the greater trochanter to the distal patella. If a Crawford fascial stripper is utilized the incision may be transverse; it is easier to harvest free-hand grafts through a longitudinal incision. The incision will be made over the fascia lata and dissection to the fascia lata is performed. Again, graft length may vary by physician. Once harvested, the graft is handed to the back table for later use. The fascia lata is not closed. The subcutaneous tissues are reapproximated and the skin closed in standard surgical fashion. An elastic bandage (ACETM) compression wrap is placed and removed anywhere from 6-24 hours later.

Suture placement

The sling is only as strong as its weakest sling, which may be the graft material, the suspension suture, or the origin or insertion site of the suspension sutures. Usually, the weakest link in an autograft or cadaver allograft is the sling edge where the suspension suture has been sutured in place. Suture pull-through at the sling edge is more common with autologous or cadaver patch slings. A running whip stitch with a #1 polydioxanone (PDS) suture is placed on each end of the graft for later placement and tensioning. Care is taken to leave even ends to the whip stitch, most often the sutured is tied down on the graft and the ends of the suture are left long.

Surgical steps

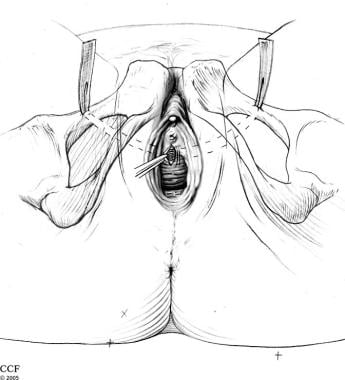

The pubovaginal sling procedure is performed through a vaginal and suprapubic incision above the pubic bone. After the patient is completely anesthetized, the patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position. Using sterile technique, prepare and drape the vagina, perineum, and suprapubic areas. Place a Foley catheter in the bladder. A transverse lower abdominal incision is made just superior to the pubic symphysis (adjustments are made if the rectus fascia is the desired graft).

Next attention is directed vaginally. The bladder neck is identified and marked. An inverted-U or a midline incision is made on the anterior vaginal wall. Dissect the vaginal wall flaps sharply off the urethra until the tip of the scissors palpates the ischiopubic rami. At this point, the endopelvic fascia is perforated immediately under the ischiopubic ramus at the superior margin of the dissection. Prior to perforation, always confirm the bladder is completely decompressed to avoid bladder injury. The index finger is then used to complete further blunt dissection freeing the retropubic space.

For placement of the sling, a Tonsil clamp, 15-degree Stamey needle, or the double-pronged ligature carrier (ie, Raz needle passer – authors' preference) is passed through the previously made Pfannenstiel incision. The index finger is placed into the vaginal incision on the ipsilateral side so that the tip of the needle is palpated. The vaginally placed finger guides the needle passer through the space of Retzius and out the ipsilateral endopelvic fascial opening created with perforation and blunt dissection.

After the passage of the needles, rigid cystoscopy is performed with the 30- and 70-degree lens. The urethra should be inspected with a short-beaked sheath. The authors find this step to be non-optional to avoid a delayed recognition of a bladder injury. The 2010 AUA Update on the Surgical Management of Incontinence states that intraoperative cystourethroscopy is considered standard of care. [32] With the bladder full, the bladder is inspected for injuries. Bilateral efflux is confirmed. If a bladder injury is seen, the needle is removed and re-passed with the bladder decompressed. The Foley is replaced once the needle passers are in place and a confirmation cystoscopy has been performed.

The ends of the graft suture are placed through the eye of the needle and the needle is pulled up through the abdominal incision. The needles are removed and the ends of the suture are brought out through the abdominal incision and tagged with hemostat clamps. The sling length should be long enough to allow it to penetrate into the retropubic space. The midpoint of the graft is approximated to the proximal third of the urethra with two simple 4-0 polyglactin (Vicryl®) sutures.

The sling may be secured before or after the vaginal incision is closed. Techniques for securing the sling are described in the section below. The amount of “tension” may vary based on the patient’s anatomy, urethral mobility, and goal to purposefully cause urinary retention or close the bladder outlet. It should be noted that there are no standardized techniques for determining the appropriate tensioning of the sling.

The vaginal incision is irrigated and inspected for hemostasis. The vaginal incision is then closed with a running 2.0 polyglactin (Vicryl®) suture.

The abdominal wound is irrigated, and hemostasis is achieved. The wound is closed in several layers to decrease the risk of seroma formation. A Foley catheter is left for drainage and a vaginal packing is placed.

Securing the sling

A critical element is tying the suspension sutures that secure the autologous graft or allograft to ensure continence without obstruction. Techniques that have been used include the following:

-

Vaginal packing, developed by Nichols in 1973

-

Spacer size of the forefinger, developed by Benderev in 1994

-

Cystoscope at 30°, developed by Raz in 1997

-

Two fingers under the sutures, developed by McGuire in 1998

-

Transvaginal ultrasonography, developed by Yamada in 1998

Mid-urethral retropubic sling

The mid-urethral retropubic sling procedure is performed through a small incision in the anterior wall of the vagina, with 2 stab incisions in lower abdomen above the pubic bone.

Place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. Prepare and drape the vagina, perineum, and suprapubic area using sterile technique. Place an 14 F Foley catheter in the bladder.

Make a small vertical incision on the anterior vaginal wall at the mid urethra. Dissect the vaginal wall tissue flaps, exposing the mid-urethra. Continue to dissect paraurethrally toward the endopelvic fascia.

Retropubic slings either be placed "top-down, " where the trocar is placed first through the suprapubic stab incision and then advanced through the space of Retzius and out the vaginal incision, or "bottom-up" where the trocar is placed from the vaginal incision and then advanced upwards through the space of Retzius out the stab incision at the suprapubic area. Here, we describe in detail the "bottom-up" approach.

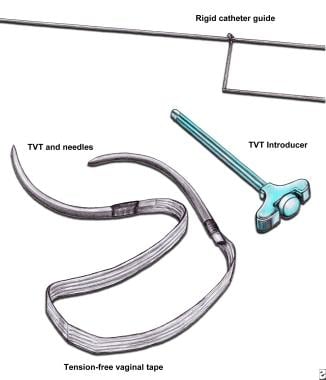

Insert the rigid catheter guide (see the image below) into the Foley catheter. Have an assistant pivot the handle of the guide to the surgeon’s left to expose the patient’s left endopelvic fascia. Puncture the patient’s left endopelvic fascia with the trocar needle, and advance the needle through the space of Retzius and to the anterior abdominal wall. The needle must hug the posterior wall of pubic symphysis during this maneuver in order to prevent a bladder injury. Tent up the abdominal skin with the needle. Incise the skin over the needle, and allow the needle to emerge.

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT). TVT device comes with polypropylene mesh tape anchored to 2 stainless steel needles. Use introducer to insert needles into space of Retzius. Use rigid catheter guide to manipulate urethra during needle insertion.

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT). TVT device comes with polypropylene mesh tape anchored to 2 stainless steel needles. Use introducer to insert needles into space of Retzius. Use rigid catheter guide to manipulate urethra during needle insertion.

Fill the bladder with 250 mL saline. Perform cystoscopy with the needle in situ to rule out bladder and urethral injury. Empty the bladder. Advance the needle and the mesh above the abdominal wall. Leave the needle in the abdomen.

Repeat the same procedure on the contralateral side. Make sure the mesh does not twist during the insertion. Cut the mesh at both abdominal ends, and remove the needles; however, leave the plastic sheath in place.

Note that the success of this operation is predicated upon performing a proper tension test. Although this device is marketed as tension-free, the surgeon must carry out the test to make sure that it is so.

Remove the plastic sheath from the mesh, and close the vaginal and abdominal incisions.

Complications, including sling erosion (into either the vagina or bladder/urethra), [33] suprapubic abscesses, and urethral sloughing, are rare. [34] However, as with any other sling procedures, the risk of urinary retention still exists. Urethral obstruction secondary to retropubic sling should be treated aggressively with urethrolysis (sling incision) within the first 3-6 weeks because the likelihood of spontaneous voiding without urethrolysis is rare. This must be a joint decision between patient and physician.

Mid-urethral transobturator tape sling

The transobturator tape (TOT) sling procedure is similar to the retropubic sling procedure; however, the needle passers are placed in the medial portion of the obturator foramen inside the groin creases at the level of the clitoris laterally. Tensioning is performed in much the same way as with retropubic sling, and the sling is placed in a tension-free manner (see the image below). Care should be taken to keep from "buttonholing" the lateral aspect of the vagina wall flap at the level of the vaginal fornices.

Mid-urethral single-incision sling ("Mini-sling")

The "mini-sling" is a form of the mid-urethral synthetic sling that uses a short piece of polypropylene mesh, placed through one small incision in the anterior vaginal wall. "Mini-slings" were developed to avoid the complications of retropubic or TOT slings. Two randomized clinical trials comparing the mini-sling to the traditional TOT sling reveal similar efficacy, safety, and mesh erosion rates. [35, 36] In addition, the trials found that women who underwent a "mini-sling" procedure reported lower intensity and a shorter duration of postoperative pain after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. [35, 36] Currently, 522 studies are underway for the new "mini-slings."

Post-Procedure

Immediate postoperative care

Typically after placement of a mid-urethral sling, the patient undergoes a trial of void in the recovery area. In the case of a pubovaginal fascial sling the patients typically are admitted for observation. On the following morning, remove vaginal packing and IV lines. Also, remove the dressing over the incision(s). Discharge patients from the hospital with pain medications 1-3 days after surgery.

If suprapubic tubes are placed, instruct patients to check postvoid residual volumes via the suprapubic catheter. Remove the suprapubic catheter when patients are able to void spontaneously; this may be as early as a day after surgery or may take as long as 3 weeks. If patients still are experiencing retention at 3 weeks, remove the suprapubic tube and teach the patient self-intermittent catheterization.

Expected outcomes

From the AUA 2010 review on surgical management of SUI, estimated cure/dry rates associated with autologous fascial sling without prolapse surgery ranged between 90% at 12 to 23 months and 82% at 48 months or longer. [32]

Success rates for retropubic and transobturator mid-urethral slings have been cited at 77.3% and 72.3%, respectively. [37] Patient satisfaction is as high as 86-88%. [37] The frequency of de novo urgency incontinence or worsening urinary urgency is 5-10%. [37] Mesh exposure is seen in about 5% of retropubic slings and 3% of transobturator slings. [37] Patients who have undergone a retropubic mid-urethral sling have higher rates of voiding dysfunction requiring surgery at about 3% and more post-operative and urinary tract infections at about 17%. [37] Groin pain is a risk that is more likely to occur with the TOT sling, at a rate of about 10%. [37]

A 2017 Cochrane review showed a significantly greater improvement in patient-reported SUI symptoms, both within and after 1 year, with autologous fascia. There was no evidence of a difference in perioperative complications or postoperative morbidity between autologous fascia and other materials. [38] However, the studies were small and had short-term follow‐up, particularly regarding mesh-related complications. In addition, the studies did not stratify outcomes based on preoperative severity of SUI.

Complications

Hemorrhage

Bleeding during transvaginal sling surgery is often troublesome and may be challenging to correct. Bleeding invariably occurs when the surgeon punctures the endopelvic fascia to facilitate the passage of suspension sutures. The technique of puncturing the endopelvic fascia is performed by many surgeons blindly under digital guidance. If one is not careful, heavy bleeding may ensue.

To prevent transvaginal hemorrhage, the authors advocate dissecting the anterior vaginal wall off the endopelvic fascia under direct vision. The plexus of veins is located at the 10- and 2-o’clock positions at the level of the bladder neck. Thus, proper anatomic dissection under direct vision allows preservation and avoidance of these veins when the endopelvic fascia is punctured. If one is concerned that these veins may become lacerated, these veins may be ligated prophylactically using 4-0 polyglactin in a figure-eight fashion.

If heavy bleeding is encountered, the application of direct pressure on the anterior vaginal wall slows down the bleeding and gives the surgeon more time to obtain better exposure. Then, one may suture-ligate the offending vessel under direct vision. These vessels are always located at the edges of the endopelvic fascia. Then, the sling is placed quickly, and the suspension sutures are tied.

The authors do not advocate packing the space of Retzius through the hole in the endopelvic fascia, because this may worsen the bleeding. Furthermore, stopping the bleeding suprapubically is not necessary because the offending vessel is never identified.

Urethral obstruction

Serious complications from sling surgery are uncommon. However, urethral obstruction may occur with any sling surgery. [39, 40] The degree of obstruction reflects the patient’s voiding symptoms. Complete obstruction results in urinary retention, whereas partial obstruction manifests with voiding symptoms (eg, hesitancy, straining, urgency, urge incontinence).

For pubovaginal fascial slings, methods to prevent urethral obstruction include placing 2 fingers under the suspension sutures when biological bladder neck slings are created, using a spacer, placing vaginal packing, angling a cystoscope at 30°, and using transvaginal ultrasonography to assess the proper urethrovesical angle as the suspension sutures are tied.

In spite of all of these precautions, the risk of urethral obstruction still exists, and the experience of the surgeon determines whether obstruction occurs. Mid-urethral synthetic slings require some small amount of space between the sling and urethra and assurance that the sling will not spring up when placed.

Recurrent or persistent stress urinary incontinence

Approximately 5-10% of patients have recurrent or persistent SUI after sling surgery. Reasons for failure include (1) suture pull-through from the edge of the sling, (2) early degradation of sling material, (3) improper placement of the sling, and (4) making the sling too loose.

Suture pull-through from the sling edge is more common with autologous and cadaver tissues, whereas early degradation of sling material is isolated to cadaver allografts. Both of these conditions result in loss of either anatomic support or adequate resting urethral closure pressure. If the sling is placed too proximally (eg, bladder) or too loosely, inadequate resistance to the proximal urethra develops.

If the pubovaginal fascial sling is too loose, some authors recommend suprapubic sling revision before resorting to complete sling reconstruction. A suprapubic sling revision is performed with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. A suprapubic incision is made, and the suspension sutures are dissected out. Ipsilateral suspension sutures are pulled up.

The cotton swab test and the bladder leak test are performed. The cotton swab should be at zero degrees with respect to the floor, and the bladder should leak moderately when filled with 500 mL of water. The suspension sutures are affixed to the rectus fascia on the contralateral side, and the incision is closed.

Urgency urinary incontinence

New-onset urge incontinence or worsening urge incontinence is a potential complication of any sling surgery. Approximately 10-30% of patients may manifest de novo urge symptoms, whereas 50-60% may experience resolution or improvement of preoperative urge incontinence.

De novo urge incontinence usually is temporary and many times resolves over several weeks. Persistent urge incontinence may be treated successfully with pelvic floor exercises and bladder-relaxing medications, alone or in combination. De novo urge symptoms and frequency may be a sign of bladder outlet obstruction, even without high postvoid residual volumes, and the surgeon must be aware of this occurrence.

Urinary retention

Women who undergo surgery to construct a sling are at significant risk of urinary retention. Although temporary in most cases, urinary retention may last a month or more. Permanent urinary retention may occur after 2-30% of pubovaginal sling surgeries.

While the condition persists, institute self-catheterization. As an alternative to catheterization, take down the surgery either by cutting the suspension suture or by freeing up the sling (ie, urethrolysis [41] ). Successful urethrolysis allows spontaneous voiding in 77-85% of women with urinary retention. To prevent recurrence of SUI after surgery, some surgeons perform the operation again at the time of urethrolysis, although this is not advised.

Other complications

Complications specifically associated with the use of autologous, cadaver, and synthetic slings include sling infection and tissue erosion. The incidence of sling infection and erosion is higher when a synthetic biomaterial is used.

Methods for avoiding sling erosion include the following:

-

Maximize the surgical exposure, and operate under direct vision. (The authors use a headlight and a self-retaining Lone-Star retractor.)

-

Employ meticulous surgical technique, and handle tissues gently.

-

Dissect in a nice avascular anatomic plane between the pubocervical fascia and the anterior vaginal wall to create thick anterior vaginal wall flaps, and use smaller midline incisions.

-

Make sure the sling is unfurled completely, using the 6-point fixation technique.

-

Tie the suspension sutures loosely enough to prevent obstruction, yet snugly enough to cure the incontinence. (The authors use the weight-adjusted spacing nomogram.)

Vaginal erosion associated with synthetic mesh slings is treated with excision of the sling. The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position under general anesthesia. Vaginal inspection reveals the exposed sling. Often, the sling material is protruding through the poorly healed vaginal incision. The sling material is either dissected out or simply pulled down with an Allis clamp, and the body of the sling is excised, leaving the suspension sutures intact. The vaginal wall is irrigated with antibiotic solution and closed.

For urethral erosions, the sling may be excised transvaginally, transurethrally, or both in combination. Then, the urethra is reconstructed by using a Martius labial fat pad graft as necessary. The vaginal wall is irrigated with antibiotic solution and closed.

Bowel perforation is a unique complication of retropubic mid-urethral sling surgery. [42]

Intact DNA material has been detected in commercially processed cadaver allografts. Whether these genes truly are infectious remains unknown. Proper informed consent must be obtained when cadaver allografts are used.

Long-term monitoring

Patients return to the clinic for follow-up after surgery for removal of the catheter if it is left in place. Otherwise, the patient returns later if the catheter was removed in the recovery room.

Patient education

For patient education resources from WebMD, see the Urinary Incontinence & Overactive Bladder Health Center, Prolapsed Bladder, and Uterine Prolapse.

-

The female urethra is composed of 4 separate tissue layers that keep it closed. The inner mucosal lining keeps the urothelium moist and the urethra supple. The vascular spongy coat produces the mucus important in the mucosal seal mechanism. Compression from the middle muscular coat helps to maintain the resting urethral closure mechanism. The outer seromuscular layer augments the closure pressure provided by the muscular layer.

-

The female urethra contains an internal sphincter and an external sphincter. The internal sphincter is more of a functional concept than a distinct anatomic entity. The external sphincter is the muscle strengthened by Kegel exercises.

-

The pubourethral ligaments suspend the female urethra under the pubic arch.

-

The pelvic diaphragm (ie, levator ani musculature) is composed of pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, ischiococcygeus, and coccygeus muscles. It contains 3 openings through which the rectum, urethra, and cervix pass.

-

This is the side view of the pelvic diaphragm. The pelvic diaphragm supports the pelvic organs (eg, bladder, uterus, rectum).

-

This photo illustrates a variety of pelvic organ prolapses, including grade-IV cystocele, uterine descensus, enterocele, and rectocele alone or in combination. In situations where a significant prolapse (eg, uterus, bladder) has occurred, evaluate for possible ureteral obstruction at the level of the pelvic inlet.

-

A cotton swab angle greater than 30° denotes urethral hypermobility. Figure 1 shows that the cotton swab at rest is zero with respect to the floor. Figure 2 shows that the cotton swab at stress is 45° with respect to the floor.

-

This illustration shows videourodynamic equipment (Aquarius XLT, Laborie Medical Technologies) used for evaluation of a patient with incontinence.

-

Videourodynamics allow a comprehensive evaluation of a patient with incontinence. Information provided by videourodynamics includes filling cystometrogram, abdominal leak point pressure, pressure-flow, static and voiding cystograms, and electromyogram recordings.

-

A flexible cystoscope is used to evaluate the anatomy of the bladder and the urethra. A flexible cystoscope is less rigid and more comfortable for the patient than the rigid cystoscope.

-

This shows normal findings from a dynamic retrograde urethroscopy; the urinary sphincter is closed at rest (Figure a), closed with stress maneuvers (Figure b), and has excellent guarding reflex (Figure c). Note the urinary sphincter is contracted and elevated in Figure c; this is a normal guarding reflex.

-

This shows classic type-II stress urinary incontinence seen on dynamic retrograde urethroscopy. Note that the sphincter is closed at rest (Figure a), remains open with stress maneuvers (Figure b), and has good guarding reflex (Figure c). Patients with classic type-II stress urinary incontinence are able to close their urinary sphincters voluntarily.

-

This shows classic type-III stress urinary incontinence seen on dynamic retrograde urethroscopy. Note that the sphincter is open at rest (Figure a), remains open with stress maneuvers (Figure b), and has weak guarding reflex (Figure c). Patients with classic intrinsic sphincter deficiency a have difficult time closing their urinary sphincters voluntarily.

-

Diagram shows 6-point fixation technique that allows even, lateral dispersion of force vectors on implanted sling. Edges of sling proper are affixed to underlying pubourethral fascia to prevent folding over or migration. When force vectors are lateralized rather than directed anteriorly toward pubis, tendency to pull up on sling to cause urethral obstruction is reduced.

-

When weight-adjusted spacing nomogram is used for women with normal body weight, tie sling sutures over shod-covered hemostats by leaving 2-mm gap between hemostat and rectus fascia. For women who are obese, increase this gap incrementally according to amount by which they exceed ideal body weight (eg, 2-mm gap/25 lb). When using this method, tie suspension sutures looser for women who are obese.

-

Weight-adjusted spacing nomogram. To tie suspension sutures on abdominal side, gauge tension on suspension sutures in inverse proportion to the patient's body weight. Before tying suspension sutures, clamp sutures with shod-covered hemostats to prevent inadvertent pulling up of sutures.

-

Rectus fascia or fascia lata pubovaginal sling. Harvest long ribbon of fascia from abdomen or from side of leg (eg, fascia lata), place under bladder neck, and secure to lower abdomen below skin.

-

Rectus fascia or fascia lata suburethral (patch) sling. Prepare short strip of fascia from abdomen or from side of leg, place under bladder neck, and hang by suspension sutures tied over suprapubic area.

-

Vaginal wall suburethral sling.

-

Gore-Tex suburethral sling. Implant short strip of Gore-Tex under bladder neck, and support it with suspension sutures tied adjacent to pubic bone.

-

One ampule of indigo carmine is administered intravenously. Cystoscopy is performed to confirm that suspension sutures have not traversed bladder. Clear efflux of blue urine indicates ureteral patency.

-

Lead-pipe urethra (Figure a) converted to normal urethra with excellent mucosal coaptation (Figure b) by means of proper sling surgery. Surgery cured this patient of stress urinary incontinence.

-

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT). TVT device comes with polypropylene mesh tape anchored to 2 stainless steel needles. Use introducer to insert needles into space of Retzius. Use rigid catheter guide to manipulate urethra during needle insertion.

-

Transobturator sling.