Practice Essentials

Tumors of the adrenal cortex are reported in 2% of all autopsies, with the most common lesion being a benign adenoma (see the first image below). The common major pathologic entities of the adrenal gland that require surgical intervention are primary hyperaldosteronism (ie, Conn syndrome, see the second image below), Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma. However, many adrenal glands are removed en bloc as part of a radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma.

Homogeneous, well-defined, 7-HU ovoid mass is seen in the right adrenal gland; this finding is diagnostic of a benign adrenal adenoma.

Homogeneous, well-defined, 7-HU ovoid mass is seen in the right adrenal gland; this finding is diagnostic of a benign adrenal adenoma.

Background

Frequently, lesions metastatic to the adrenal gland necessitate adrenalectomy, and reports exist of adrenal excision for symptomatic adrenal cysts. The workup of adrenal disorders requiring surgical intervention has undergone a revolution with the tremendous advances in hormonal research, as well as in radiographic techniques and localization. In general, neoplastic lesions of the adrenal gland may be classified with the tumor, node, metastases (TNM) staging system, as follows:

-

Tumor

T1 - Tumor confined to adrenal gland and less than 5 cm

T2 - Tumor confined to adrenal gland and greater than 5 cm

T3 - Tumor invasion into periadrenal fat

T4 - Tumor invasion of adjacent organs

-

Node

N0 - Negative lymph nodes

N1 - Positive lymph nodes

-

Metastases

M0 - No metastases

M1 - Distant metastases

Table. TNM Staging System for Neoplastic Lesions of the Adrenal Gland (Open Table in a new window)

Stage |

TNM |

Stage I |

T1, N0, M0 |

Stage II |

T2, N0, M0 |

Stage III |

T3, N0, M0 or T1-2, N1, M0 |

Stage IV |

Any T, N, M1, or T3-4, N1, M0 |

History of the Procedure

The adrenal gland is crucial to endocrine homeostasis, and maladies associated with it result in several recognized syndromes. Understanding of the adrenal glands began in 1805, when Currier first delineated the anatomic structure of the medulla and cortex. Addison later described the clinical effects of adrenal insufficiency in 1855. Thomas Addison first described the association of hypertensive episodes with adrenal tumors in 1886. Medical and surgical management of pheochromocytoma was first described in the United States by Mayo [1] and remained relatively unchanged until the 1960s, when Crout et al elucidated the biochemical pathways and diagnostic catecholamine studies, allowing diagnostic ability prior to exploration. [2]

Problem

Primary hyperaldosteronism

First described in 1955 by Jerome Conn, the hallmarks of primary hyperaldosteronism are hypertension, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, and elevated urine aldosterone levels (with salt repletion), as well as decreased renin activity and alkalosis with increased urinary potassium excretion. Primary hyperaldosteronism can be secondary to an adrenal adenoma or secondary to bilateral adrenal hyperplasia. Differentiating between these two disease processes is important because they can be treated differently. The patient's renin level should also be checked to rule out causes of secondary hyperaldosteronism, such as renal artery stenosis. The renin level is elevated in persons with renal artery stenosis, whereas the renin level is suppressed in those with primary hyperaldosteronism.

Cushing syndrome

The diagnosis of Cushing syndrome is made based on abnormalities of urinary and plasma cortisol and/or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The syndrome typically is attributed to central, hypothalamic, or pituitary excess secretion of ACTH (Cushing disease), primary adrenal hypercorticalism, or ectopic secretion of ACTH.

Pheochromocytoma

These tumors arise from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla. Ten percent of cases may be familial, and 10% might be bilateral or in extra-adrenal locations. If the tumor arises from a site other than the adrenal, it is termed a paraganglionoma. Paraganglionomas have been reported in locations from the neck to the pelvis. While pheochromocytoma follows the "rule of 10s," with only 10% of cases involving malignant tumors, 50% of cases of paraganglionomas have reported malignancies. Pheochromocytomas also can be a part of an endocrine syndrome such as multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) IIa, MEN IIb, von Hippel-Lindau disease, or von Recklinghausen disease.

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastomas arise from sympathetic neuroblasts and occur almost exclusively in the pediatric population. Neuroblastoma represents the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, and approximately one third of neuroblastomas arise in the adrenal gland. Surgery of neuroblastoma is an important element in diagnosis, staging, and treatment of children with neuroblastoma. Surgery is curative therapy for patients with stage I and early stage II disease, with a reported 2-year survival rate of 89%. [3] Reviews regarding safety reveal a low complication rate, commonly less than 10%. Advanced-stage tumors usually require a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy to provide a complete response.

Myelolipoma

Adrenal myelolipomas are rare benign masses that consist of fat and hematopoietic cells. They are hormonally inactive. These masses are typically asymptomatic, but some are associated with flank or abdominal pain. Adrenal myelolipomas can often be diagnosed with imaging studies. On CT scans, myelolipomas appear as well-circumscribed massed with a negative attenuation consistent with fat. Should the diagnosis still be in doubt, obtaining an image-guided needle biopsy can be helpful. As myelolipomas are benign lesions with no hormonal activity, most physicians recommend observation unless symptoms occur or the tumor begins to grow during observation.

Adrenocortical carcinoma

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare disease with a poor prognosis. Up to 80% of adrenal carcinomas are functional and secrete multiple hormones.

Pathophysiology

Primary hyperaldosteronism

The hallmarks of primary hyperaldosteronism are hypertension, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, and elevated urine aldosterone levels (with salt repletion), as well as decreased renin activity and alkalosis with increased urinary potassium excretion. The most common causes of aldosterone overproduction are idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia, followed by adenomas, and then (rarely) adrenal carcinoma. Of the benign adenomas, approximately 60% are unilateral (typically managed surgically), while 40% are bilateral lesions that are treated medically with spironolactone, unless marked asymmetry of aldosterone production is present. In this case, the dominant gland often is excised, unless bilateral disease that is uncontrollable by medical therapy exists.

Cushing syndrome

The syndrome typically is attributed to central, hypothalamic, or pituitary excess secretion of ACTH (Cushing disease), primary adrenal hypercorticalism, or ectopic secretion of ACTH.

Pheochromocytoma

These tumors arise from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla. Presentation of the pheochromocytoma varies with the production of active metabolites. Most commonly, episodic alpha-adrenergic hypersecretion leads to intermittent malignant hypertension.

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastomas arise from sympathetic neuroblasts and occur almost exclusively in the pediatric population. Neuroblastoma represents the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, and approximately one third of neuroblastomas arise in the adrenal gland. They are rapidly growing tumors and may be metabolically active; however, the more common presentation is from mass effect.

Adrenocortical carcinoma

As the name implies, adrenocortical carcinoma arises from the cortex. The adrenal cortex in made up of 3 distinct zones: glomerulosa (outer), fasciculata (middle), and reticularis (inner). These 3 zones are responsible for aldosterone, cortisol, and sex steroid production, respectively. Up to 80% of adrenal carcinomas are functional and secrete multiple hormones. The most common hormones secreted are glucosteroids, followed by androgens, estradiol, and, finally, aldosterone. Adrenal carcinomas can be subclassified according to their ability to produce adrenal hormones.

Etiology

Primary hyperaldosteronism

The most common causes of aldosterone overproduction are idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia, followed by adenomas, and then (rarely) adrenal carcinoma. Of the benign adenomas, approximately 60% are unilateral (and typically managed surgically), while 40% are bilateral lesions.

Cushing syndrome

See Cushing syndrome in Pathophysiology.

Pheochromocytoma

See Pheochromocytoma in Pathophysiology.

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastomas arise from sympathetic neuroblasts and occur almost exclusively in the pediatric population. Approximately one third of neuroblastomas arise in the adrenal gland.

Myelolipoma

Many theories have been proposed as to the etiology of myelolipomas. The most widely accepted theory is adrenocortical cell metaplasia and growth due to an insult to the adrenal gland (eg, infection, ischemia).

Adrenocortical carcinoma

See Adrenocortical carcinoma in Pathophysiology.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the United States, tumors of the adrenal cortex are reported in 2% of all autopsies, with the most common lesion being a benign adenoma. The incidence of adrenal carcinoma is estimated to be 1 case per 1.7 million, and it accounts for 0.02% of all cancers.

Presentation

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Presentation of primary hyperaldosteronism includes hypertension, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, and elevated urine aldosterone levels (with salt repletion), as well as decreased renin activity and alkalosis with increased urinary potassium excretion.

Cushing syndrome

The clinical presentation of Cushing syndrome is hypertension, moon facies, abdominal striae, buffalo hump, muscle weakness, amenorrhea, decreased libido, osteoporosis, fatigue, hirsutism, and obesity.

Pheochromocytoma

Presentation of the pheochromocytoma varies with the production of active metabolites. Pheochromocytoma most often develops in young–to–middle-aged adults. The classic triad is episodic headache, tachycardia, and diaphoresis. The most common clinical sign of pheochromocytoma is hypertension. Persons with this condition may experience sustained hypertension, paroxysmal hypertension, or sustained hypertension with superimposed paroxysms. Other common signs are palpitations, anxiety, tremulousness, chest pain, and nausea and vomiting. A small group of these patients experience induced myocardiopathy due to sustained catecholamine release. They present with decreased cardiac function and congestive heart failure. Generally, the cardiomyopathy is reversible with the use of antiadrenergic blocking agents and alpha-methylparatyrosine, a catecholamine synthesis inhibitor.

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastomas arise from sympathetic neuroblasts and occur almost exclusively in the pediatric population. Neuroblastoma represents the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, and approximately one third of neuroblastomas arise in the adrenal gland. They are rapidly growing tumors and may be metabolically active; however, the more common presentation is from mass effect.

Adrenocortical carcinoma

These patients present with constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, fever, and malaise. Up to 80% of adrenocortical carcinomas are functional, and patients with these present with clinical signs of Cushing syndrome. An increase in sex steroid levels can result in oligomenorrhea, virilization, or feminization.

The most common presentation of adrenocortical carcinoma is that of an incidentaloma. At presentation, 19% have inferior vena cava (IVC) involvement and 32% have metastases.

Lesions metastatic to the adrenal gland

Adrenal masses thought to arise from distant metastases include melanoma, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and breast cancer. These should be discussed with the primary service taking care of these lesions, but these adrenal masses are often amenable to laparoscopic adrenalectomy.

Indications

In deciding whether adrenalectomy is indicated for a newly discovered adrenal mass, one must ascertain whether the mass is functional and if it has signs of malignancy. Except for bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, which can be treated medically with spironolactone, most functional masses should be surgically removed.

Signs of malignancy

Signs of malignancy are based on tumor size, radiographic findings, and history of carcinoma.

Tumor size

Studies have shown that adrenal masses larger than 6 cm have a much greater chance of malignancy. Because CT scans tend to underestimate the size of the tumor by more than 20%, the cutoff on CT scan for an adrenal mass should be 4-6 cm. Therefore, adrenal masses larger than 4-6 cm on CT scan are considered high risk for cancer and should be surgically removed.

Radiographic findings

Adrenocortical carcinomas and pheochromocytomas have been shown to be hyperintense on MRI T2–weighted images. If the intensity of the adrenal lesion relative to the liver or spleen on an MRI T2–weighted image is less than 80%, the lesion is more likely to be a cortical adenoma. CT scan findings suggestive of an adrenocortical carcinoma include lesions that have irregular margins, are heterogeneous, and have high densities on noncontrast images. Necrosis and calcification are also more commonly associated with adrenal carcinoma. Most adenomas are lipid rich and have densities of less than 10 Hounsfield units. Furthermore, the density of adenomas on delayed contrast images is reduced by at least 60%, unlike adrenocortical carcinomas. Finally, nuclear scans such as metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) and NP-59 (131-6-β-iodomethylnorcholesterol) can help to identify pheochromocytomas and adrenocorticalcarcinomas, respectively.

History of carcinoma

Patients with a history of carcinoma and a newly discovered adrenal mass have a 32%-73% chance of having metastasis to the adrenal gland. The most common cancers that metastasize to the adrenal glands are melanoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, and renal cancer. Biopsy of an adrenal lesion is appropriate in a patient with a history of cancer. If the biopsy sample is positive for metastasis, the decision of whether to give chemotherapy, with or without adrenalectomy, should be further explored. In most settings, adrenalectomy would not be indicated in the presence of metastases. Metastatic disease, unless part of a research protocol, is a contraindication to adrenal surgery.

Adrenal incidentalomas

Attention must be given to the increasing diagnosis of the adrenal incidentaloma, which refers to a clinically inapparent adrenal mass that is discovered with some form of imaging study performed for an indication not related to adrenal disease. Estimates of the prevalence of adrenal incidentalomas range from 0.1%-4.3%. Current National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommendations dictate that patients with such a diagnosis should undergo hormonal evaluation, including an overnight dexamethasone suppression test, plasma-free metanephrine study, and a study of plasma aldosterone level–plasma renin activity ratio. [4] In general, adrenal incidentalomas associated with abnormal hormonal findings should undergo surgical adrenalectomy. Masses larger than 6 cm are associated with a 25% risk of malignancy, and these should also be treated surgically.

If a mass is nonfunctional and has no signs of malignancy (ie, >6 cm), the patient can be monitored and observed. The patient should undergo CT scanning every 6 months and an annual endocrine evaluation for 4 years. If the mass grows or affects endocrine function, it should be removed. Some clinicians now believe that if the mass is stable as revealed by CT scan at 3 and 12 months and is not functional, routine follow-up is not required.

Relevant Anatomy

Before describing surgical technique, understanding the anatomy of the adrenal glands is essential. The adrenal glands, also known as suprarenal glands, belong to the endocrine system. They are a pair of triangular-shaped glands, each about 2 in. long and 1 in. wide. The suprarenal glands are responsible for the release of hormones that regulate metabolism, immune system function, and the salt-water balance in the bloodstream; they also aid in the body’s response to stress.

Both adrenals are located on the superior posterior aspect of the kidneys in the retroperitoneum. The right adrenal is covered anteriorly by the liver and has a short vein typically draining directly into the inferior vena cava (IVC). The left adrenal is covered anteriorly by the pancreas and spleen. In general, the surgical approach is dependent on the primary adrenal lesion, the size of the lesion, the side of the lesion, and the habitus and health of the patient, as well as surgeon preference and familiarity.

For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Suprarenal (Adrenal) Gland Anatomy.

Prognosis

Primary hyperaldosteronism

The surgical removal of the adrenal gland and adenoma provides excellent results, with most patients being cured.

Pheochromocytoma

Long-term cures are rare in cases of malignant pheochromocytomas. In cases of metastatic disease, 5-year survival rates as high as 36% have been reported.

Neuroblastoma

Surgery of neuroblastoma is an important element in diagnosis, staging, and treatment of children with neuroblastoma. Surgery is curative therapy for people with stage I and early stage II disease, with a reported 2-year survival rate of 89%. Reviews regarding safety reveal a low complication rate, most commonly less than 10%. Advanced-stage tumors usually require a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy to provide a complete response.

Adrenocortical carcinoma

At presentation, 19% of patients had IVC involvement and 32% had metastases. The median time of survival was 17 months, and evaluation of factors affecting survival reveal benefit to the following characteristics: age younger than 54 years, absence of metastasis, and nonfunctional tumors. [5] Another study at Memorial Sloan-Kettering reviewed 115 patients and revealed overall median survival to be 38 months, with a 5-year survival rate of 37%. Patients with stage I or II disease fared better, with a 5-year survival rate of 60%, while patients with stage III and IV disease had a 5-year survival rate of 10%.

Complications of adrenal surgery

The keys to adrenal surgery are exposure and dissecting the body away from the tumor. Most preventable complications arise from failure to strictly adhere to these principles. Certainly, the most troublesome complication occurs from avulsion of the short right adrenal vein. Manual compression and good exposure allow the avulsed area of the cava to be partially occluded with sponge sticks, and the vein stump may be grasped with an Allis forceps and subsequently suture ligated. In addition, on the right side, the accessory hepatic veins can be avulsed and are handled using a similar manner of vascular control and then ligation.

On the left side, complications typically involve splenic laceration or damage to the tail of the pancreas. Dissection superiorly on either adrenal involves the possibility of entering the pleura, with subsequent pneumothorax. Finally, being aware of the possible need for postoperative supplementation of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids in the patient with complex and/or bilateral disease is essential.

-

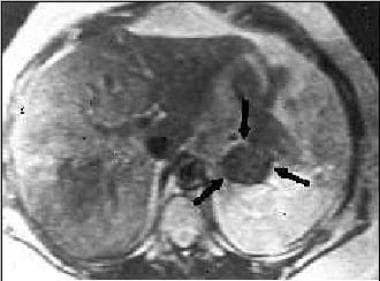

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in a patient with Conn syndrome showing a left adrenal adenoma.

-

Homogeneous, well-defined, 7-HU ovoid mass is seen in the right adrenal gland; this finding is diagnostic of a benign adrenal adenoma.