Practice Essentials

Suicide rates increased 37% between 2000 and 2018 and decreased 5% between 2018 and 2020. However, suicide rates increased 2.6% from 2021 to 2022. In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, with 48,183 deaths. This is about one death every 11 minutes. The number of people who think about or attempt suicide is even higher. In 2021, an estimated 12.3 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.5 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.7 million attempted suicide. [1]

Suicide affects all ages. Rates of suicide are highest in people ages 85 and older. Men aged 75 and older have the highest rate (42.2 per 100,000) compared to other age groups. Adults aged 35–64 years account for 46.8% of all suicides in the United States, and suicide is the 8th leading cause of death for this age group. Youth and young adults ages 10–24 years account for 15% of all suicides, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for this age group, accounting for 7,126 deaths. [1]

Globally, an estimated 703,000 people take their own lives annually. [2] Of these global suicides, 77% occur in low- and middle-income countries. [3]

Suicide-related activities and characteristics

Numerous activities are associated with suicidal potential, including the following:

-

Making a will

-

Getting the house and affairs together

-

Unexpectedly visiting friends and family members

-

Purchasing a gun, hose, or rope

-

Writing a suicide note

-

Visiting a primary care physician - A significant number of people see their primary care physician within 3 weeks before they commit suicide [4]

Suicidal individuals have a number of characteristics, including the following:

-

A preoccupation with death

-

A sense of isolation and withdrawal

-

Few friends or family members

-

An emotional distance from others

-

Distraction and lack of humor - They often seem to be "in their own world" and lack a sense of humor (anhedonia)

-

Focus on the past - They dwell on past losses and defeats and anticipate no future; they voice the notion that others and the world would be better off without them

-

Haunted and dominated by hopelessness and helplessness

Assessment of suicide risk

A clear and complete evaluation and clinical interview with regard to the following are used to determine the need for suicide intervention:

-

Suicidal ideation - Determine whether the person has any thoughts of hurting himself or herself

-

Suicide plans - If suicidal ideation is present, the next question must be about any plans for suicidal acts; the general formula is that more specific plans indicate greater danger

-

Purpose of suicide - Determine what the patient believes his or her suicide would achieve; this suggests how seriously the person has been considering suicide and the reason for death

-

Potential for homicide - Any question of suicide also must be coupled with an inquiry into the person's potential for homicide

-

Protective factors - Work with the patient to identify "reasons for living." Ask about personal relationships, future events, long-term goals, etc.

-

"What would you do if you feel suicidal?"

Signs and risk factors

The following is a list of 13 things that should alert a clinician to a real suicide potential:

-

Patients with definite plans to kill themselves - People who think or talk about suicide are at risk; however, a patient who has a plan (eg, to get a gun and buy bullets) has made a clear statement regarding risk of suicide

-

Patients who have pursued a systematic pattern of behavior in which they engage in activities that indicate they are leaving life - This includes saying goodbye to friends, making a will, writing a suicide note, and developing a funeral plan

-

Patients with a strong family history of suicide - A family history of suicide is especially indicative of suicide risk if the patient is approaching the anniversary of a family member’s suicide or the age at which a relative committed suicide

-

The presence of a gun, especially a handgun

-

Psychotic symptoms especially in adolescents - Kelleher et al reported in a prospective cohort study of 1112 school-based adolescents (aged 13-16 y), that 7% of the total sample reported psychotic symptoms at baseline. Of that subsample, 7% reported a suicide attempt by the 3-month follow-up compared with 1% of the rest of the sample. The authors concluded that adolescents with psychopathology who report psychotic symptoms are at clinical high risk for suicide attempts. Psychotic symptoms in adolescents may serve as a marked for that population being at high suicidal risk. [5]

-

Being under the influence of alcohol or other mind-altering drugs - Drug abuse is especially significant if the drugs are depressants

-

If the patient encounters a severe, immediate, unexpected loss, such as when a person is fired suddenly or left by a spouse

-

If the patient is isolated and alone

-

If the person has a depression of any type

-

If the patient experiences command hallucination - A command hallucination ordering suicide can be a powerful message of action leading to death

-

Discharge from psychiatric hospitals - Patients are at suicide risk upon discharge from a psychiatric hospital, which is a very difficult time of transition and stress; the structure, support, and safety of the institution are no longer available to the patient

-

Anxiety - Anxiety in all of its forms leads to a risk of suicide; the constant sense of dread and tension proves unbearable for some

-

Clinician's feelings - Regardless of what the patient says or does, it matters if the clinician has a feeling that the patient is going to commit suicide

Mental status review

Looking at the following patient characteristics, the mental status review is designed to focus on evaluating an individual's potential for committing suicide:

-

Appearance - In addition to noting the dress and hygiene of patients who are depressed (eg, disheveled, unkempt and unclean clothing), the clinician should assess these individuals for physical evidence of suicidal behavior, such as wrist lacerations and neck rope burns

-

Affect - One specific concern is a flat affect by the patient when describing his or her thoughts and plans of suicide and self-destructive behavior

-

Thoughts - Three types of thought changes represent areas for major focus and concern: (1) command hallucinations (usually auditory) telling the patient to kill himself or herself, (2) delusions about the benefits of suicide (eg, family will be better off), (3) an obsession with taking his or her own life

-

Homicidal potential

-

Judgment, insight, and intellect

-

Orientation and memory - The focus of this part of the mental status review is to determine if the person is delirious or has dementia

Intervention

Intervention for a suicidal patient should consist of multiple steps, as follows:

-

The individual must not be left alone

-

Anything that the patient may use to hurt or kill himself or herself must be removed

-

The suicidal patient should be treated initially in a secure, safe, and highly supervised place; inpatient care at a hospital offers one of the best settings

After the initial intervention, which usually includes hospitalization, it is critical that there be in place an ongoing management treatment plan.

Pharmacologic therapy

Treatment of a patient’s underlying psychiatric illness consistently appears to be the most effective use of pharmacologic therapy in suicidal persons.

Overview

Suicide rates increased 37% between 2000 and 2018 and decreased 5% between 2018 and 2020. However, suicide rates increased 2.6% from 2021 to 2022. In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, with 48,183 deaths. This is about one death every 11 minutes. The number of people who think about or attempt suicide is even higher. In 2021, an estimated 12.3 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.5 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.7 million attempted suicide. [1]

Suicide affects all ages. Rates of suicide are highest in people ages 85 and older. Men aged 75 and older have the highest rate (42.2 per 100,000) compared to other age groups. Adults aged 35–64 years account for 46.8% of all suicides in the United States, and suicide is the 8th leading cause of death for this age group. Youth and young adults ages 10–24 years account for 15% of all suicides, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for this age group, accounting for 7,126 deaths. [1]

Globally, an estimated 703,000 people take their own lives annually. [2] Of these global suicides, 77% occur in low- and middle-income countries. [3]

This phenomenon is even more compelling because, in many instances, suicides can be prevented. Therefore, clinicians must recognize the risk factors for suicide as a way of intervening in a self-destructive event and cycle.

This article discusses the following:

-

Basic terminology applied to self-destructive activities and events

-

Risk factors that can alert the clinician to early warning signs of suicide

-

Interventions if a person's attempt at suicide is imminent

-

The diagnosis and treatment of the underlying mental disorder causing the self-destructive behavior

-

Appropriate actions for a clinician if a person being treated does commit suicide

Depression, isolation, previous suicide attempts, substance abuse, and serious mental illness rank as highly significant contributors to suicide. Swift and decisive interventions based on a thorough assessment can save lives. Preventing a person's suicide death, however, is only the first step in the treatment of the suicidal patient.

Diagnostic and treatment considerations

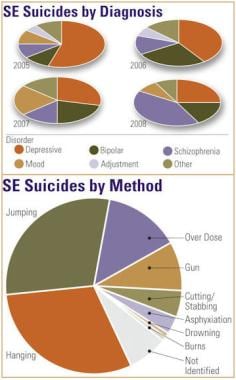

Once it has been assured that the patient is safe, the reasons for the individual’s self-destructive behavior must be found. The diagnosis requires a complete psychiatric history and mental status examination. (See the chart below.)

Sentinel event (SE) suicides by diagnosis and method. Courtesy of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

Sentinel event (SE) suicides by diagnosis and method. Courtesy of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

The choice of treatment is dictated by the specific mental illness affecting the patient. Talking therapies can help, and in many instances, medication can alleviate symptoms of mental illness. However, despite intervention, if the patient does die by suicide, a number of steps can and should be undertaken for the patient's family, other patients, the staff, and the therapist.

Terminology

Suicide means killing oneself. The act constitutes a person willingly, perhaps ambivalently, taking his or her own life. Several forms of suicidal behavior fall within the self-destructive spectrum.

Death by suicide means the person has died. It is important not to use the term successful suicide; the goal is to prevent suicide and provide treatment.

A suicide attempt involves a serious act, such as taking a fatal amount of medication and someone intervening accidentally. Without the accidental discovery, the individual would be dead.

A suicide gesture denotes a person undertaking an unusual, but not fatal, behavior as a cry for help or to get attention.

A suicide gamble is one in which patients gamble their lives that they will be found in time and that the discoverer will save them. For example, an individual ingests a fatal amount of drugs with the belief that family members will be home before death occurs.

A suicide equivalent involves a situation in which the person does not attempt suicide. Instead, he or she uses behavior to get some of the reactions that suicide would have caused. For example, an adolescent boy runs away from home, wanting to see how his parents respond. (Do they care? Are they sorry for the way that they have been treating him?) The action can be seen as an indirect cry for help.

Etiology

A number of factors correlate with serious suicide attempts and taking one's life by suicide, including, but not limited to, the following:

-

Medications

-

Mental illness

-

Sex

-

Genetics

-

Availability of firearms

-

Life experiences

-

Physical illness

-

Economic instability and status

-

Media and the Internet

-

Psychodynamic formulation

-

Meaninglessness

-

Discharge from a psychiatric hospital

An understanding of the causes of suicidal behavior will not only clarify the roots of the patient’s self-destructive path but also help the clinician to determine the appropriate treatment for the patient. Once the patient is safe, then the underlying dynamics can be addressed.

Medications

A number of medications have been linked to suicidal behavior, which has prompted the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to require a warning on certain prescription drugs, including antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and analgesics.

Antidepressants

Initially, the FDA and studies linked antidepressants to childhood and adolescent self-destructive events and required a warning for those populations; however, Schneeweiss and colleagues found the same linkage for adults as well. [6]

The investigators reviewed data from all 287,543 residents of Canada's British Columbia, 18 years or older, who had been placed on an antidepressant between 1997 and 2005 and concluded the following: "Our finding of equal event rates across antidepressant agents supports the US Food and Drug Administration's decision to treat all antidepressants alike in their advisory. Treatment decisions should be based on efficacy, and clinicians should be vigilant in monitoring after initiating therapy with any antidepressant agent." [6]

Anticonvulsants

In 2008, the FDA required a suicidal behavior warning be placed on anticonvulsants. In a 2010 exploratory analysis, Patorno and colleagues suggested that the use of gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and tiagabine, compared with the use of topiramate, may be associated with an increased risk of suicidal acts or violent deaths. [7]

Pain medication

Tramadol is a narcoticlike pain reliever that, on May 26, 2010, received an FDA addition of a suicide risk warning (tramadol hydrochloride [Ultram] and tramadol hydrochloride/acetaminophen [Ultracet]). [8] The FDA noted linkage between tramadol prescriptions and patients with emotional instability and suicidal ideation and increased self-destructive behavior. [8]

Smoking cessation medications

Moore et al determined that the risk of depression and suicidal or self-injurious behaviors is substantially increased and statistically significant with the use of varenicline. Risk was also present, but smaller, with bupropion, and was even smaller with nicotine replacement. The investigators suggested that varenicline is unsuitable as a first-line agent to aid in smoking cessation. [9]

Glucocorticoids

A study by Fardet et al concluded that glucocorticoids increase the risk of suicidal behavior and neuropsychiatric disorders. The authors reviewed data from all adult patients in UK general practices from 1990 to 2008. Of 786,868 courses of oral glucocorticoids prescribed for 372,696 patients, there were 109 incident cases of suicide or suicide attempt and 10,220 incident cases of severe neuropsychiatric disorders. [10]

Mental illness

Although mental illness is generally linked to premature deaths, certain mental illnesses carry with them remarkably high lifetime instances of suicide. In fact, 95% of people who commit suicide have a mental illness. In a general sense, mental illness all too often is an isolating experience, with such isolation correlating with suicide.

Hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder is quite prevalent in the suicidal population, [11] including for people with any depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias, substance abuse problems, delirium, and dementia, as well as certain genetic factors. A study assessing the risk for suicide during the 90 days after hospital discharge found that adults with complex psychopathologic disorders with prominent depressive features appear to have a particularly high short-term risk for suicide. The study included approximately 1.8 million people, including a cohort of inpatients aged 18 to 64 years in the Medicaid program who were discharged with a first-listed diagnosis of a mental disorder and a 10% random sample of inpatients with diagnoses of nonmental disorders. [12]

Each psychiatric disorder has its own distinctive mental status footprint. A mental status review is designed to help evaluate a person’s suicide potential.

The following list represents some of the mental disorders frequently associated with suicidal behavior, but self-destructive thoughts and acts also may occur in other diagnoses:

-

Alcoholism

-

Anxiety disorders

-

Bipolar affective disorder

-

Bulimia nervosa

-

Cocaine-related psychiatric disorders

-

Delirium

-

Depression

-

Hallucinogens

-

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

-

Opioid abuse

-

Personality disorders

-

Postpartum depression

-

PTSD

-

Schizophrenia

-

Seasonal affective disorder

-

Social phobia

-

Tramatic Brain Injury (TBI)

-

Vascular dementia

Depression

Because depression involves a preoccupation with death, the twin killers of hopelessness and helplessness, and withdrawal, it is a major contributor to suicide. A dangerous time in depression occurs when a patient is coming out of the deepest part of the experience. At that point, the individual may mobilize his or her newly acquired energy to commit suicide.

The protracted and profound emotional roller coaster of manic-depressive illness puts a patient at risk both during the depressive phase and in the psychosis of mania. Suicide is a particular risk when executive functions and judgment have been compromised by bipolar disorder. [13] In particular, men with bipolar disorder have an increased risk for suicide. [14]

One important consideration in the treatment of depression is that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a lower rate of fatal overdoses than do tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). [15]

Shah et al found that in adults younger than 40 years, depression and history of attempted suicide are significant independent predictors of premature cardiovascular disease and ischemic heart disease in males and females. [16]

An intriguing notion is emerging regarding the link between evidence of inflammation and suicidal thoughts in patient with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Holmes and colleagues have examined levels of translocator protein (TSPO) in MDD patients. TSPO is an indicator of neuroinflammation. Using positron emission tomography, they found significantly elevated levels of TSPO in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in MDD patients with suicidal thoughts compared to those patients without suicidal thinking. [17]

Bipolar disorder

Patients with bipolar disorder are at risk for suicidal behavior, especially those with an early onset of symptoms. Goldstein and associates followed the mental health of 413 youths diagnosed with bipolar disorders and found that 76 (18%) attempted suicide at least once within 5 years of study, of these, 31 (8% of the overall group and 41% of those who attempted suicide) made many attempts. They concluded that bipolar disorder with early onset is associated with high suicide rates. The severity of depression and family history must be considered in assessment of individuals with bipolar disorder. [18]

In 2015, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force on Suicide published a meta-analysis indicating that female gender, younger age at illness onset, and comorbid anxiety disorder are associated with suicide attempts in bipolar patients while male gender and a family history of suicide in a first-degree relative is associated with suicide deaths. [19]

Numerous international studies of lithium use have documented anti-suicidal effects in patients with affective disorders since the 1970s. [20]

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenic patients are at a significantly high risk for suicide. They may experience hallucinations, often auditory, such as voices commanding them to kill themselves (command hallucinations). In addition, these individuals may, in the context and as a result of their illness, become depressed; they realize that they are different from others.

Persons with schizophrenia may also have moments of insight during which they realize that they may not achieve some life goals that others can accomplish. Individuals who are considered highly functional seem to be at high risk for suicide, perhaps because of their ability to appreciate how they are different from others and how their life is different from what they wish it to be.

Finally, the suspicions and fears associated with schizophrenia may promote isolation and withdrawal.

The high rate of suicide in patients with schizophrenia is higher when physical comorbidity or substance abuse is also present. [21]

A 2-year study comparing the risk for suicidal behavior in patients treated with clozapine versus olanzapine was conducted in 980 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 26.8% of whom were refractory to previous treatment, who were considered at high risk for suicide because of previous suicide attempts or current suicidal ideation. Results show that clozapine was superior to olanzapine in preventing suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder at high risk for suicide. [22]

Although there is at least modest evidence suggesting that antipsychotic medications protect against suicidal risk, the evidence appears to be most favorable for second-generation antipsychotics, particularly clozapine, which is the only medication approved by the US FDA for preventing suicide in patients with schizophrenia. [23]

Anxiety disorders and OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and phobic disorders have symptoms that make suicide a possibility. Persons struggling with these symptoms feel frightened, terrorized, isolated, and physically paralyzed by feelings of anxiety, panic, and dread that often seem inexplicable. In many instances, people feel that the symptoms are growing, expanding, and becoming incapacitating.

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) in college students have been linked to suicidality. Researchers studied a cohort of 474 college students who attended mental health screenings at two private universities and completed multiple self-report questionnaires. Data show the presence of one or more OCS was associated with an increased odds ratio of suicide risk of approximately 2.4. After controlling for depressive symptoms however, presence of OCS was no longer a significant risk factor. Of the OCS assessed, only obsessions about speaking or acting violently remained an independent risk factor for suicidality over and above depression. [24]

A study of 36,788 OCD patients in the Swedish National Patient Register between 1969 and 2013 found that after adjusting for psychiatric comorbidities, the risk was reduced but remained substantial for both death by suicide and attempted suicide. Within the OCD cohort, a previous suicide attempt was the strongest predictor of death by suicide. Having a comorbid personality or substance use disorder also increased the risk of suicide. Being a woman, higher parental education and having a comorbid anxiety disorder were protective factors. Data show that patients with OCD are at a substantial risk of suicide. [25]

A study by Katz et al showed that panic attacks and panic symptoms in individuals with a major mood disorder meeting criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), may carry an increased risk of suicidal ideation. This ideation may progress to suicide attempts, especially in individuals with prominent catastrophic cognitions. [26] An example would be a woman with agoraphobia who becomes progressively more isolated and depressed by her inability to leave her home.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Survivors of trauma (eg, childhood sexual abuse, recent physical devastation, physical/emotional abuse) struggle with flashbacks and nightmares. These individuals frequently alternate between periods of hypervigilance and periods of psychic numbing.

Veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan experience a high rate of PTSD—with many struggling with feelings of being damaged and with feelings of guilt—and have a historically high rate of suicide. [27, 28, 29]

Postdeployment readjustment problems affecting veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) are well documented, but the possible relationship of readjustment stressors to the increase in military suicides is not.

Kline et al found that after adjusting for mental health and combat exposure, veterans with the highest number of readjustment stressors had a 5.5 times greater risk of suicidal ideation than those with no stressors. This suggests that suicide prevention efforts that more directly target readjustment problems in returning OEF/OIF veterans are needed. [30]

Substance abuse

Substances can contribute to self-destructive behaviors in all 3 phases of their use—intoxication, withdrawal, and chronic usage. A depressed person commonly becomes acutely suicidal after a few drinks. Similarly, some people can become suicidal after ingesting lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Still others encounter depression during substance withdrawal and respond by killing themselves.

According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, emergency department (ED) visits involving drug-related suicide attempts increased 41% from 2004 to 2011, from an estimated 161,586 to 228,366 visits. There was a total of about 1.5 million ED visits involving drug-related suicide attempts between 2004 and 2011. [31]

A person who engages inchronic alcohol and drug use often experiences a number of major losses, including of his or her job, spouse, and family, and these, in turn, contribute to the individual becoming suicidal. [14]

Even persons in drug recovery programs remain at risk. For example, patients in opiate dependency programs, especially those with chronic pain, those with the availability of firearms, those who use other street drugs, and those new to the program, are at particular risk. [32]

In a US study, Bohnert et al found that suicide and overdose are connected, yet distinct, problems. Patients who have a history both of suicide attempts and of nonfatal overdoses may have poor psychological functioning, as well as a more severe drug problem. [33]

The physical and mental health effects associated with methamphetamine (MA) use have been documented; however, little is known about the effects of injection MA and suicidal behavior.

The Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) found that MA injection was associated with an 80% increase in the risk of attempted suicide, suggesting that individuals who inject MA should be monitored for suicidal behavior. The study elicited information regarding sociodemographics, drug use patterns, and mental health problems, including suicidal behavior. Of 1873 eligible participants, 149 (8%) reported a suicide attempt. [34]

Cannabis is the most commonly used drug of abuse by adolescents in the world. Yet, little is known about the impact of cannabis use on mood and suicidality in young adulthood. Gobbi et al reviewed longitudinal and prospective studies, assessing cannabis use in adolescents younger than 18 years (at least 1 assessment point). [35] They ascertained the development of depression in young adulthood (ages 18 to 32 years) and employed odds ratios (OR) to adjust for the presence of baseline depression and/or anxiety and/or suicidality. After adjustment, the OR of developing depression in young adulthood with adolescent use of cannabis compared with no cannabis use was 1.37. The OR for suicidal ideation was 1.50, and the OR for suicide attempt was 3.46. The researchers conclude that although individual-level risk remains moderate to low, the high prevalence of adolescents consuming cannabis generates a large number of young people who could develop depression and suicidality attributable to cannabis. This is an important public health problem and concern, which should be properly addressed by health care policy. [35]

Delirium and dementia

Delirium and dementia involve the loss of memory, disorientation, hallucinations, delusions, and poor judgment. These conditions often lead to self-destructive behavior. An example might be an accountant who slowly starts to have difficulty remembering numbers and solving addition problems. Although others might view these problems as minimal, he may feel that he is losing his mind and career, leading him to take his own life.

Traumatic brain injury

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been linked to increased risk of suicide. Bryan and Clemans have noted the association of multiple TBIs as a risk factor. They studied a group of patients that included 161 military personnel referred for evaluation and treatment of suspected head injury at a military hospital's TBI clinic in Iraq. They found depression, PTSD, and TBI symptom severity significantly increased with the number of TBIs. They concluded that suicide risk is higher among military personnel with more lifetime TBIs, even after controlling for clinical symptom severity. [36, 37]

In another study, researchers looked at a registry-based retrospective cohort study from Denmark that included 34,529 deaths by suicide over 35 years. They compared individuals with medical contact for TBI with the general population without TBI and found that patients with TBI had an increased risk of suicide (incident rate ratio of 1.90). [38]

Bulimia

Bulimia has been accompanied by suicidal activity. Predisposing factors include feelings of loneliness, stimulant use, family history of psychiatric disorders, childhood abuse, and difficulty dealing with the public. [39]

Sex

There is a distinct difference in suicide rates by sex. Men have a significantly higher rate of completed suicides than do women. There are nearly 4 times the number of completed suicides among men than among women. [40] However, women have a much higher rate of suicide attempts. Often, women select methods, such as an overdose of medication, that allow more time for intervention. Men frequently use methods such as firearms, which are much more lethal.

Females more often use poison when attempting suicide. A study by Hoon et al investigated the risk factors associated with the repetition of deliberate self-poisoning. The associated factors for repeat suicide attempt were sex (female), living without a family, using antidepressants, and a history of psychiatric treatment. Early psychological intervention and close observation is required for patients meeting these criteria. (See the chart below.) [41]

Genetics

Some authorities believe that genetic factors alone may be involved in suicide, that suicide runs in families, and that having a relative who commits suicide is indeed a risk factor. Therefore, a family history of suicide is very significant. Careful assessments of family history of mental illness and suicide should be a routine aspect of patient evaluation.

Studies continue to show the gene connection in suicidal behavior. Genes related to serotonin have been implicated in histories of second suicide attempts. [42] In a study of postmortem brains and living cohorts, Guintivano et al found evidence of a genetic and epigenetic link between suicide and a single-nucleotide polymorphism in SKA2, a gene involved in cortisol suppression and stress regulation. [43, 44] Many of the discussed mental illnesses (eg, bipolar disorder) are not only risk factors for suicide but also have strong genetic components.

Family history

A family history of suicidal behavior represents a significant risk factor for the same behavior in offspring. Researchers determined that the association is stronger with maternal suicidal behavior versus paternal suicidal behavior and that the risk is increased more in children than in adolescents or adults. [45]

Availability of firearms

The leading method of suicide in the United States remains firearms, and is more common in men than women. [46, 47] According to provisional data from the CDC, 26,993 people died by gun suicide in 2022, .

When a person with a depressed mood consumes alcohol and has a handgun available, the situation can easily turn lethal.

Therefore, a psychiatrist must inquire not only into the patient's suicidal ideation and plans but also into the presence of firearms. Clinicians also must know their state statutes concerning persons with mental illness possessing firearms. [48] Of interest, the limiting of the purchasing of firearms by local and state background checks has decreased the rate of suicide by guns. [49]

Morgan et al examined data from the National Firearms Survey, a nationally representative Web-based survey of US adults conducted by Growth for Knowledge in April 2015. A total of 3949 participants were presented with 4 options on the intent and means of violent death (homicide with a gun, homicide with a weapon other than a gun, suicide with a gun, and suicide by a method other than a gun) and asked to rank order the frequency of these outcomes in their state in an average year. They found that between 2014 and 2015, more suicides than homicides occurred in every state. Suicide by firearm was the most frequent cause of violent death in 29 states. [50]

Data from the National Institute of Mental Health on the differences between men and women and the method of suicide are as follows: [51]

-

Suicide by firearms - Males (55.6%), females (31.4%)

-

Suicide by suffocation - Males (28.4%), females (29.0%)

-

Suicide by poisoning - Males (8.2%), females (30.0%)

Physical illness

Suicide is often encountered in patients who have a severe medical problem. The risk for suicide increases in the face of a protracted, painful, progressively debilitating disease.

For example, patients undergoing dialysis for end-stage renal disease have a higher rate of suicide than that of the general population. [52] Other diseases conferring a higher suicide risk include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), quadriplegia, multiple sclerosis, severe whole-body burns, and chronic heart failure.

A study by Webb et al found a significant link between physical illnesses and suicidal behavior in primary care patients. Coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and osteoporosis were linked with increased suicide risk among all patients. Elevated risk of suicide was due to clinical depression in all patients, excluding those with osteoporosis.

However, 2 groups of women in the study—those younger than 50 years who were physically ill and older women with multiple physical diseases—were found to have an elevated suicide risk even after depression had been adjusted for. [53]

Cancer represents a risk factor as well. One study analyzed the risk of suicide across cancer sites, with a focus on survivors of head and neck cancer (HNC). Results show there were 404 suicides among 151,167 HNC survivors from 2000 to 2014, yielding a suicide rate of 63.4 suicides per 100,000 person-years. In this timeframe, there were 4493 suicides observed among 4219,097 cancer survivors in the study sample, yielding an incidence rate of 23.6 suicides per 100,000 person-years. Compared with survivors of other cancers, survivors of HNC were almost 2 times more likely to die from suicide. The mortality rate due to suicide for head and neck cancers was surpassed only by that of pancreatic cancer (63.4 vs 86.4 suicides per 100,000 person-years). Although survival rates in cancer have improved because of improved treatments, the risk of death by suicide remains a problem for cancer survivors, particularly those with head and neck cancer HNC. [54]

Another study examining suicide among cancer patients found that out of 8,651,569 cancer patients, 13,311 committed suicide. Researchers noted the relative risk of suicide, compared with the general population, is highest in those persons with cancers of the lung, head and neck, and testes, and those with Hodgkin lymphoma. [55]

Asthma has also been linked to suicide, particularly in young people. [56, 57] The combination of cancer and age is particularly lethal. [58] Persons experiencing increasing intractable pain are at particularly high risk for suicide.

There is a possible link to suicide in patients with migraine and fibromyalgia. Researchers examined a population of patients with migraine and found that those who also had a diagnosis of fibromyalgia (FM) had a high instance of suicide ideation and attempts. [59]

Surviving major physicial trauma may be a risk factor for suicide. One study explored the idea that major injury survivors have high rates of morbidity and mortality. Researchers found that survivors of major trauma are at a heightened risk of developing mental health conditions or death by suicide in the years after their injury. Furthermore, they noted patients with pre-existing mental health disorders or who are recovering from a self-inflicted injury are at particularly high risk. [60]

Life experiences

Certain recent life events can precipitate suicidal behavior. These include romance-related losses, such as the termination of a love relationship or a divorce, a job termination, or the loss of a pet. The acute loss can be devastating. [61]

A number of past life events are also linked to suicide. The most important is suicide by a family member or a friend. Not infrequently, history of a father, mother, or sibling committing suicide correlates with suicide by another member of that family.

Suicide by a friend may provoke others to duplicate the event; indeed, suicide has a contagious aspect, especially among adolescents. [62] Not uncommonly, one suicide in a high school is followed by other suicides or attempts. In fact, bereavement for a person who has completed suicide stands as a significant risk factor. Researchers examined 3432 eligible respondents aged 18–40 years who were bereaved by suicide of a friend or relative after the age of 10. Results showed that adults bereaved by suicide had a higher probability of attempting suicide than those bereaved by sudden natural causes, suggesting that bereavement by suicide is a specific risk factor for suicide attempt among young bereaved adults. [63]

As discussed earlier, persons with PTSD are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These individuals may have a history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse. Damage to the person leads to self-destructive actions.

One study found that sexual violence and having witnessed violence were significant predictors of lifetime suicide attempts. [64] This study, which examined the possible link between trauma exposure and suicidal behavior, was conducted with 4351 adult South Africans from 2002-2004 as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Surveys. A 2014 meta-analysis reached similar conclusions. [65, 66] Future research is needed to better understand how and why these experiences in particular increase the risk of suicidal outcomes.

Victimization by bullying is another experience that has emerged as a correlate to suicidal behavior, and attention must be paid to this in the suicide assessment. In a landmark study by Klomek et al of 5302 children in Finland born in 1981, the authors found evidence that bullying at age 8 years was linked to self-destructive behavior later in life. [67] When controlling for depression and conduct symptoms, suicide attempts and completions in later life in females were significantly correlated to bullying. However, the same correlation was not apparent for males. [67]

More evidence that being bulliedin childhood leads to self-injurious behavior in adolescence was provided by a study conducted by Fisher et al. The authors analyzed data for 2141 children in the UK and found that among children aged 12 years who had self harmed (2.9%; n=62), more than half were victims of frequent bullying (56%; n=35). Exposure to frequent bullying predicted higher rates of self-harm even after accounting for other risk factors such as emotional and behavioral problems, low IQ, and family environmental risks. [68]

In recent years bullying has come to be recognized as one of the most important factors in suicidal behavior. Koyanagi et al sampled 134,229 adolescents aged 12–15 years and found the overall prevalence of suicide attempts and bullying victimization to be 10.7% and 30.4%, respectively. After adjusting for sex, age, and socioeconomic status, bullying victimization was significantly associated with higher odds for a suicide attempt in 47 of the 48 countries studied. [69]

Economic instability and status

Times of economic change, especially economic depressions, have also been associated with suicides. The start of the Great Depression in the United States was accompanied by a number of suicides.

Job loss has long been associated with increased suicidal ideation and behavior. Emile Durkheim demonstrated a correlation between times of economic decline and employment decreases and a rise in completed suicides. However, there has always been the companion assumption that these suicides occurred mostly among the adult population.

Gassman-Pines and colleagues have shown that youth suicidal activities are also exacerbated by job loss. They looked at 1997 to 2009 data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey and the Bureau of Labor Statistics to estimate the effects of statewide job loss on adolescents' suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide plans. They found job losses among 1% of a state's working-age population increased the probability of adolescent girls and Blacks reporting suicide-related behaviors by 2 to 3 percentage points. Job losses did not affect the suicide-related behaviors of boys, non-Hispanic Whites, or Hispanics. They concluded that adolescents, like adults, are affected by economic downturns. [70]

Durkheim noted that in times of major societal alternations, when the rules are in flux and people do not know what is expected of them, the self-destructive rate increases. He had observed that not only did the suicide rate increase with a rise in unemployment but also that a soaring economy led to heightened suicide activity. He termed this period of major cultural changes anomie.

Poverty and low income, with concomitantly fewer options and opportunities, also correlate with suicide. [11]

Media and the Internet

Media can be a suicidal factor in negative and positive ways. The Internet, and other media, can provide information concerning "how-to" methods. A 2008 study found many Websites providing specific techniques on suicide. [71] That same study also found many antisuicide sites and a surprising number of prosuicide sites.

Books can also have a negative impact on suicide. A patient, after reading the book Final Exit, used one of the methods described to complete a suicide. Furthermore, antipsychiatric Internet sites are available that decry mental health explanations and, for example, show ways to be more effective at being anorexic. The Internet has also been used to broadcast suicides and has been a tool for the development of suicide pacts. [72]

However, a number of Web sites do provide encouragement for treatments, accounts of successful interventions, and key resources. [73] In addition, individuals have used the Internet to take online questionnaires that can indicate depression and suicide potential; some college students were found to have sought treatment as a result of taking these surveys. [74]

It is well known that media notice of a celebrity who takes their life by suicide leads to increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors. One study examined the daily suicide data, call volume to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL), and visits to two suicide prevention websites before and after entertainer Robin Williams' death on August 11, 2014. They concluded that daily suicide deaths, calls to NSPL, and visits to two suicide prevention websites dramatically increased after Williams took his own life. [75]

Contagion

Suicidal behavior, especially amongst adolescents, has been linked to other adolescents complete and attempted suicide. Swanson and Colman looked at the association between exposure to suicide and suicidality outcomes in youth. They used baseline information from the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth between 1998-1999 and 2006-2007, with follow-up assessments 2 years later. This included 8766 youth aged 12-13 years, 7802 patients aged 14-15 years, and 5496 patients aged 16-17 years. They determined that knowing someone who had committed suicide was associated with increased suicidality outcomes for all age groups. Exposure to suicide predicts ideation and attempts. [76]

Psychodynamic formulation

Several individual psychodynamic ways of viewing suicide exist. In one situation, patients deflect anger inward to hurt themselves when they want to strike out at others. An example would be a young person taking a drug overdose to punish his or her parents after being grounded for misbehavior.

Alternately, the psychoanalytic notion exists of incorporation and killing the interject. In this situation, patients have unconsciously incorporated an ambivalently held object (eg, a family member). For example, a man incorporates his father. He then attacks the interject (father) by killing himself.

Impulsivity

In many cases, suicidal behavior results from a person acting impulsively. Burton and colleagues showed that a lack of executive functioning in the form of poor impulse control inhibition represents a suicide risk. Impulsivity can often separate people who just have suicidal ideation from those who actually attempt suicide. [77]

However, Spokas et al have suggested that impulsive attempts have valid significance and are similar to premeditated attempts with regard to completed suicide risk. [78] Hence, an assessment of the patient’s impulse control is critical.

Other risk factors

A number of other factors are closely linked to suicide, including marital status, perceived/actual incarceration, lack of exposure to daylight, and even geographic altitude.

Marital status

People who are married are less suicidal than are those who are single, divorced, or widowed. Isolated individuals are at greater risk for suicide than are those involved with others and their community.

Geographic altitude

A study by Kim et al described altitude as a risk factor for suicide. [79] Their study concluded that when gun ownership, altitude, and population density are considered as predictor variables for suicide rates on a state-by-state basis, altitude is a significant independent risk factor. Thus, the higher the altitude, the higher the risk of suicide. [79] This association may be related to metabolic stress associated with mild hypoxia in individuals with mood disorders.

Incarceration and hospitalization

If an individual feels or is indeed trapped, especially those who are incarcerated, they are at suicide risk. Prisoners have a high rate of suicide; this is common during the first hours to first week of being placed in confinement. [80, 81] In contrast, during the first week after a patient's discharge from a psychiatric hospital or unit, the risk of suicide is particularly high. [82] For many, the transition is difficult, challenging, and anxiety provoking.

The risk of suicide should be extended to all persons involved with the criminal justice system. Webb et al determined that major health and social problems frequently coexist in this population, including offending, psychopathology, and suicidal behavior. [83] Further prevention strategies are needed for this group, including improved mental health service provision for all people in the criminal justice system, even those found not guilty and those not given custodial services. Better coordination is needed in public services to tackle coexisting health and social problems.

Lack of daylight

Lack of daylight correlates with depression and suicide. Regions with long, dark winters, such as Scandinavia and parts of Alaska (eg, Nome), have high suicide rates. Indeed, persons with seasonal affective disorder (SAD) who live in these regions experience depression in the absence of sunlight and, hence, have a higher susceptibility to depression, which may lead to suicide.

Climate change

According to a large study analyzing temperature and suicides across the United States and Mexico, rising temperatures are linked to increasing rates of suicide. Results show that the rate of suicide rose by 0.7% in the United States and by 2.1% in Mexico when the average monthly temperature rose by 1C. Hotter periods resulted in more suicides irrespective of wealth and the usual climate of the area. Researchers project that unmitigated climate change could result in a combined 9000–40,000 additional suicides across the United States and Mexico by 2050. [84]

Serum cholesterol

A correlation has long been noted between low levels of total serum cholesterol and suicidal activity. Olié and associates found lower cholesterol levels in persons who attempted suicide, suggesting serum cholesterol levels could possibly be used as a biologic marker for potential suicide risk. [85]

Sleep problems

Sleep difficulty remains an indicator for not only depression and anxiety disorders but also a risk factor for suicide. Bjørngaard and colleagues studied sleeping problems and suicide in 75,000 Norwegian adults for 20 years. They concluded that problems with sleeping, perhaps in combination with or as a consequence of anxiety and depression, should be considered a marker of suicide risk. [86]

A team of researchers from Yale University found that people with severe restless legs syndrome (RLS) are more likely to plan and attempt suicide than people without RLS, even after controlling for depression. The team investigated the frequency of lifetime suicidal behavior in 198 patients with severe RLS and 164 controls. All participants completed the Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R) and the Brief Lifetime Depression Scale. Results show significantly more patients with RLS than controls were at high suicide risk (SBQ-R score ≥ 7) and had lifetime suicidal thoughts or behavior, independent of depression history. [87]

Military suicides

There has been a recent dramatic increase in suicides among military personnel. In the search for causes, researchers examined the association between deployment and suicide among all 3.9 million US military personnel who served during Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom. They also explored suicides that occurred after separation from military service.

Results did not support an association between deployment and suicide mortality. However, results did show an increased rate of suicide associated with separation from military service regardless of deployment status. Rates of suicide were elevated among service members who separated with less than 4 years of military service or who did not separate with an honorable discharge. [88]

A study of more than 163,000 soldiers, with a focus on 9,650 soldiers who attempted suicide, found that those never deployed and women were more than three times as likely to try suicide. The study examined risk factors (sociodemographic, service related, and mental health), method, and time of suicide attempt by deployment status (never, currently, and previously deployed). The enlisted soldiers who had never been deployed accounted for 40.4% of all soldiers, but 61.1% of those who attempted suicide (n = 5894), with the risk of suicide highest in the second month of service. Risk among soldiers on their first deployment was highest in the sixth month of deployment and for those previously deployed, risk was highest at 5 months after return. [89]

DHA

Although more studies are needed, a report by Lewis et al suggested that low serum docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) levels may be a risk factor for suicide. The authors studied active-duty US military personnel and found that the risk of suicide death was 14% higher per standard deviation of lower DHA percentage. Among men, the risk of suicide death was 62% greater with low serum DHA status. [90]

Concussion

According to a 2016 study, concussion sustained from everyday or recreational activities triples long-term risk of suicide. The increased risk applied regardless of patients' demographic characteristics and was independent of past psychiatric conditions. Weekend concussions were associated with a one-third further increased risk of suicide compared with weekday concussions. [91, 92]

Discharge from a psychiatric hospital

The discharge period from a psychiatric hospital is considered a high-risk time for suicidal activity, particularly for discharged children and adolescents. A study of suicidality rates for children and adolescents within 30, 60, and 90 days of discharge found the average length of stay at psychiatric hospitals for children and adolescents with Medicaid-managed care (Medicaid MCO) coverage is 7.3 days. For patients covered by Medicaid fee-for-service (Medicaid FFS), the average duration is 12.5 days — a difference of 5.2 days, or 71% — which can be critical time needed to stabilize the child or adolescent before discharge back into the community. Researchers noted the 60-day suicidality rate following a psychiatric hospitalization nearly doubled for children and adolescents with insurance coverage that shifted from Medicaid FFS to Medicaid MCO following statewide expansion of managed care in May 2017. [93]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Suicide rates increased 37% between 2000 and 2018 and decreased 5% between 2018 and 2020. However, suicide rates increased 2.6% from 2021 to 2022. In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States, with 48,183 deaths. This is about one death every 11 minutes. The number of people who think about or attempt suicide is even higher. In 2021, an estimated 12.3 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.5 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.7 million attempted suicide. [1]

Suicide affects all ages. Rates of suicide are highest in people ages 85 and older. Men aged 75 and older have the highest rate (42.2 per 100,000) compared to other age groups. Adults aged 35–64 years account for 46.8% of all suicides in the United States, and suicide is the 8th leading cause of death for this age group. Youth and young adults ages 10–24 years account for 15% of all suicides, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for this age group, accounting for 7,126 deaths. [1]

According to research published in JAMA Pediatrics, suicide attempts spurring calls to poison control centers more than quadrupled among US children aged 10–12 years from 2000–2020. [94]

Several suicide-related demographic factors often occur in the same person. For example, if a male police officer with major depression and a significant problem with alcohol commits suicide using his service revolver (which, unfortunately, happens not infrequently), five risk factors are involved: sex, occupation, depression, alcohol, and gun availability.

In the United States, certain states have higher suicide rates than others. The Western states have the highest suicide rates, with the exception of Vermont. In addition, living in rural areas carries a higher risk of suicide than living in urban areas. [95]

International occurrence

Globally, an estimated 703,000 people take their own lives annually. [2] Of these global suicides, 77% occur in low- and middle-income countries. [3] Suicide rates in the African (11.2 per 100,000), European (10.5 per 100,000), and South-East Asia (10.2 per 100,000) regions were higher than the global average (9.0 per 100,000) in 2019. The lowest suicide rate was in the Eastern Mediterranean region (6.4 per 100,000). [1] Moreover, in certain cultures, suicide has been considered more acceptable than in others. For example, the Japanese culture often regarded suicide as an honorable solution to certain situations.

Remarkably, although suicide remains a major cause of death internationally, treatment of suicidal people around the world is quite lacking. Bruffaerts et al used World Health Organization (WHO) data to conclude that most people with suicidal ideation and plans and who have made suicide attempts do not receive treatment. This finding extended across various different areas around the world, especially in low-income countries. [96]

Religion-related demographics

Religion may also play a role in suicide. Historically in the United States, Protestants have had a higher rate of suicide than either Catholics or Jews. Some religions may encourage suicide in situations of disgrace or for patriotic reasons.

Race-related demographics

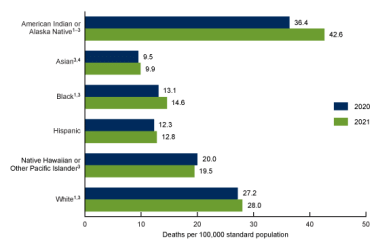

In the United States, the racial/ethnic groups with the highest rates of suicide in 2021 were non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native people and non-Hispanic White people. [1]

Age-adjusted suicide rates are highest among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) people (28.1 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic White people (17.4 per 100,000) compared to other racial and ethnic groups. Suicide is the 9th leading cause of death among AI/AN people. Non-Hispanic AI/AN people have a much higher rate of suicide (28.1 per 100,000) compared to Hispanic AI/AN people (2.0 per 100,000). The suicide rate among non-Hispanic AI/AN males ages 15–34 is 68.4 per 100,000. [1]

From 2020 to 2021, trends in suicide rates for males varied by age group (see chart below). [97]

Age-adjusted suicide rates for males, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020 and 2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Age-adjusted suicide rates for males, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020 and 2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

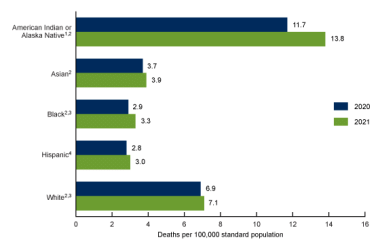

From 2020 to 2021, suicide rates increased 14% for non-Hispanic Black (subsequently, Black) females (from 2.9 deaths per 100,000 standard population to 3.3) and 3% for non-Hispanic White (subsequently, White) females (6.9 to 7.1). (See chart below.) [97]

Age-adjusted suicide rates for females, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020 and 2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Age-adjusted suicide rates for females, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020 and 2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Suicide is the 12th leading cause of death for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic people of all races. Between 2019 and 2020, age-adjusted suicide rates decreased 4.5% among non-Hispanic White persons. At the same time, they increased 4.0% among non-Hispanic Black and 6.2% among non-Hispanic AI/AN people. [1]

Furthermore, in sampling surveys (one from 53 countries and one from 43 countries), Voracek et al found that regardless of sex or age, people with a lighter skin color have a higher rate of suicide than do those with darker skin color. [98]

Although suicide rates for children aged younger than 12 years are significant, they have rarely been studied from a racial perspective. In 2015, researchers reviewed national mortality data on suicide in children aged 5 to 11 years in the United States from January 1, 1993, to December 31, 2012. The results showed that although the overall suicide rate in school-aged children in the United States appeared stable over the 20 years of study, there was a significant increase in suicide incidence in black children and a significant decrease in suicide among white children. [99]

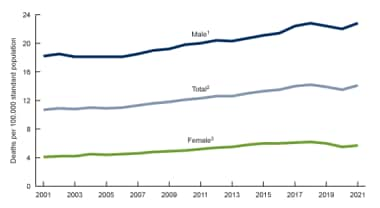

Sex-related demographics

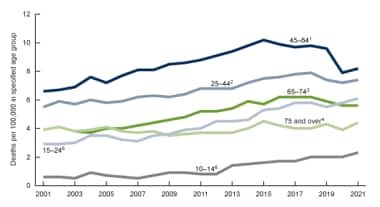

The relationship between sex and suicide represents one of the most salient and enduring features in suicide-related statistics. Men commit suicide far more frequently than women. In the United States, the difference is quite striking. In 2020, men died by suicide 3.88x more than women. In the same year, White males accounted for 69.68% of suicide deaths. [40] During 2001–2021, the suicide rate for males was three to four and one-half times the rate for females (see chart below). [97]

Age-adjusted suicide rates, by sex: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Age-adjusted suicide rates, by sex: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

However, women make 2-3 times more suicide attempts than men do. [100] Furthermore, the sex differential continues in those who are suicidal who seek help; females are much more prone to go for medical and psychiatric aid then men are. [101]

Although the facts can be interpreted in many ways, including as they relate to method (men use firearms, and women use poison) and the ability to handle feelings, the fact remains that difference in frequency related to sex is a powerful and relatively consistent finding across a wide range of other demographic categories, such as age, socioeconomic factors, and region.

Age-related demographics

In general, the suicide rate increases with age, with a major spike in adolescents and young adults. In recent decades, the number of adolescent suicides has increased dramatically. The 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance showed that 6.9% of high school students had attempted suicide in the year before the survey. [102]

In a study of 6483 adolescents aged 13–18 years of age and their parents, Nock et al found lifetime prevalences of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts of 12.1%, 4%, and 4.1%, respectively. Most meet the criteria for at least 1 DSM-IV disorder. This led them to conclude that suicidal behaviors are common among US adolescents. The rates are close to those found in adults. [103]

Although adolescents generally have a high suicide rate and are at risk, certain subcultures have an even higher risk. One such subculture is called "alternative," which includes individuals who describe themselves as "Goth," "Emo," and "Punk." Young and colleagues looked at 452 German school students aged 15 years. They found that teenagers who were in the alternative subgroup self-injured more frequently (45.5% vs 18.8%), repeatedly self-injured, and were 4-8 times more likely to attempt suicide (even after adjusting for social background). The study concluded that approximately half of these adolescents' self-injure, primarily to regulate emotions and to communicate distress. However, a minority self-injure to belong to the group. Alternatively, some subculture groups, such as "Jocks," channel anxieties into activities such as exercise. [104]

Nearly one-third of young people who die of suicide have nonfatal self-harm events during the last 3 months of life. One study found that adolescents and young adults were at markedly elevated risk of suicide after nonfatal self-harm. The 12-month suicide standardized mortality rate ratio after self-harm was significantly higher for adolescents (46.0, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 29.9–67.9) than young adults (19.2, 95% CI: 12.7–28.0). Among these high-risk patients, those who used violent self-harm methods, particularly firearms, were at especially high risk. [105]

Mars et al studied 456 adolescents who reported suicidal thoughts and 569 who reported non-suicidal self-harm at 16 years of age. They used logistic regression analyses to explore associations between a wide range of prospectively recorded risk factors and future suicide attempts, assessed at the age of 21 years. Among participants with suicidal thoughts at 16 years of age, future risk of suicide attempts was associated with non-suicidal self-harm history, cannabis use, other illicit drug use, higher intellect and openness scores, and exposure to self-harm in others. Among participants with non-suicidal self-harm at baseline, the strongest predictors were cannabis use, other illicit drug use, sleep problems (waking in the night and insufficient sleep), and lower levels of the personality type extraversion. [106]

With increasing age, a critical relationship emerges with suicide. Geriatric suicide is extremely prevalent. People older than 75 years have the highest rate of suicide. In 2007, the incidence of suicide in persons aged 75 years and older was 36.1 for every 100,000 people, compared with the national average of 11.26 suicides for every 100,000 people. [51] Suicide risk in various cities in England has been found to be 67 times higher for older adults (≥60 years) presenting with self-harm than for older adults in the general population. The highest suicide rates were found among men aged 75 years and older. [107] The older age group also maintains an alarming connection with murder-suicides. (Note the chart below for suicide figures based on sex, race, and age.) [108]

Suicide rates by age have historically noted peaks in the adolescent/young adult group and in the elderly. From 1999 to 2010, a significant increase (28.4%) was noted in the age-adjusted suicide rate for adults aged 35-64 years by 28.4%; the rate rose from 13.7 per 100,000 population to 17.6 (p< 0.001) Among men aged 35-64 years, the rate increased 27.3%, from 21.5 per 100,000 population to 27.3; the rate among women increased 31.5%, from 6.2 per 100,000 population to 8.1. The greatest increases among men were found in those aged 50-54 years and 55-59 years. Suicide rates increased with age among women, with the largest percentage increase found in those aged 60-64 years. [109]

Suicide rates for females, by age group: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Suicide rates for females, by age group: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Suicide rates for males, by age group: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Suicide rates for males, by age group: United States, 2001–2021. Courtesy of the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Occupation-related demographics

Police and public safety officers are at increased risk for suicide. The long hours of work, the scenes they witness daily, the availability of guns, and the silence encouraged by the profession (keeping within the "wall-of-blue"), as well as alcohol usage and divorce, contribute to this risk.

Firefighters also have a high incidence of suicide. In a report by National Volunteer Fire Council, they identified over 260 firefighter suicides since they started to compile data on their own rank's suicide from 1880. They noted similar dynamic causes as those found in police suidides (eg, PTSD, job stresses) and suggested prevention approaches. [110]

Physicians, especially those who deal with progressively terminally ill patients, as well as dentists, also have a high rate of suicide. In the United States, the medical field loses the equivalent of a medical school class each year by suicide. Perhaps, elements of obsessive and perfectionist tendencies combined with personal feelings of isolation may contribute to this high number of self-induced deaths. Gold et al. looked at the records of 31,636 completed suicides, of which 203 were physicians. They concluded that “inadequate treatment and increased problems related to job stress may be potentially modifiable risk factors to reduce suicidal death among physicians." [111] They essentially concluded that doctors are under a great deal of stress and are often reluctant to seek help.

In view of the high rate of physician’s suicide, Eneroth et al. looked at suicidal ideation among residents and specialists in a university hospital. Unsurprisingly, they found that some of these doctors did indeed have suicidal ideation. They concluded that residents and specialists require separate interventions based on their position in the medical hierarchy. The study also found that supportive meetings resulted in a lower level of suicidal ideation among specialists, whereas empowering leadership helped reduce suicidal ideation among residents. [112]

In 2020, Dong et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors among physicians. They found 35 eligible studies with 70,368 physicians. Results show that the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was 17.4%, while the 1-year prevalence was 8.6%, 6-month prevalence was 11.9%, and 1-month prevalence was 8.6%. The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempt was 1.8%, while the 1-year prevalence was 0.3%. [113]

Suicide risk in military personnel has been increasing. In 2020, 6,146 veterans died by suicide, and suicide was the 13th leading cause of death among veterans overall. Among veterans younger than 45 years, suicide was the second leading cause of death. In the United States, veterans account for about 13.9% of suicides among adults. [114]

Seasonal variances in suicide

Most suicides occur in the spring; the month of May particularly has been noted for its high rate of suicide. The speculation is that during the winter and early spring, people with depression are often surrounded by persons who are feeling downhearted because of the weather. However, with the arrival of the spring season and the month of May, people who are depressed because of the weather are cheered and people who are depressed for other reasons remain depressed. As others cheer up, those who remain miserable must confront their own unhappiness.

A report from the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) at the University of Pennsylvania reported December 4, 2012 on the common misperception that year-end holidays are a more frequent period for suicides compared with other times of the year. The APPC tracked press reports on this belief and compared them with the number of actual daily suicide deaths in the United States. It was determined that compared with other timeframes, the period from November to January typically has the lowest daily rates of suicide for the year. The APPC suggests that the belief that year-end seasonal holidays prompt increased suicide rates is simply a “myth.” [115]

The relationship between suicides and birthdays

Researchers examined the association between birthday and increased risk of suicide in the general population as well as in patients receiving mental health services. Using Poisson regression analysis, they observed an increased risk of suicide on day of one's birthday itself for males in both the general population (IRR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.18-1.64, p < .01) and the clinical population (IRR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.07-2.07, p = .03). This increased risk was especially significant in males aged 35 years and older. In the clinical population, risk was restricted to male patients aged 35-54 and risk extended to the 3 days prior to one's birthday. These results suggest that birthdays are periods of increased risk of suicide, particularly for men, regardless of whether or not they are receiving psychiatric care. [116]

Suicide in pregnancy

Although suicide during pregnancy and in the postnatal period is uncommon, it is associated with several important risk factors. One UK study sought to identify potential risk factors by analyzing data regarding suicides of 4785 women between the ages of 16 and 50 years. Of these women, 98 (2%) died during the perinatal period. Of the 1485 women who died by suicide between the ages of 20 and 35 years, 74 (4%) died in the perinatal period. Results show that women who died from suicide during the perinatal period were more likely to have received a diagnosis of depression compared with women who died by suicide but who were not in the perinatal period. They were also less likely to be receiving any active treatment at the time of death. [117]

The relationship between lithium in drinking water and suicide

There has been discussion about high levels of lithium being associated with decreased suicide rates. A few studies back up this claim, including those by Liaugaudaite et al, [118] Hidvégi et al, [119] and Knudsen et al. [120]

Association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and self-directed violence

A relationship between Toxoplasma gondii infection in women and self-destructive behavior was found in a study of 45,788 Danish women between 1992 and 1995. Toxoplasma-specific IgG antibodies were measured in connection with childbirth, and Pedersen et al concluded that mothers with T. gondii infection had an increased relative risk of self-directed violence compared with noninfected mothers (1.53 vs 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.27–1.85). Increasing IgG antibody levels appeared to indicate increased risk. [121]

Patient Education

It is critical for patients to appreciate that suicidal behavior reflects mental illness. Moreover, the patient's family needs to see the patient’s behavior as a sign of an underlying problem. Family members often struggle with a series of conflicting feelings about the patient’s suicidal activities. Education and an opportunity to discuss their feelings can help.

Helpful Web sites for patients include the following:

For patient education information, see the Depression Center, as well as Depression and Suicidal Thoughts.

Assessing Suicide Risk

A clear and complete evaluation and clinical interview provide the information upon which to base a suicide intervention. Although risk factors offer major indications of the suicide danger, nothing can substitute for a focused patient inquiry. However, although all the answers a patient gives may be inclusive, a therapist often develops a visceral sense that his or her patient is actually going to commit suicide. The clinician's reaction counts and should be considered in the intervention.

Suicidal ideation

Determine whether the person has any thoughts of hurting him or herself. Suicidal ideation is highly linked to completed suicide. Some inexperienced clinicians have difficulty asking this question. They fear the inquiry may be too intrusive or that they may provide the person with an idea of suicide. In reality, patients appreciate the question as evidence of the clinician's concern. A positive response requires further inquiry.

Suicide plans

If suicidal ideation is present, the next question must be about any plans for suicidal acts. The general formula is that more specific plans indicate greater danger. Although vague threats, such as a threat to commit suicide sometime in the future, are reason for concern, responses indicating that the person has purchased a gun, has ammunition, has made out a will, and plans to use the gun are more dangerous. The plan demands further questions. If the person envisions a gun-related death, determine whether he or she has the weapon or access to it.

The relationship between suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts

In 2014, 9.4 million adults aged 18 years or older who responded to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported they had thought seriously about trying to kill themselves at any time during the past 12 months. Those who had serious thoughts of suicide were then asked whether they made a plan to kill themselves or tried to kill themselves in the past 12 months. Of the 9.4 million adults with serious thoughts of suicide, 2.7 million reported they had made suicide plans, and 1.1 million made a nonfatal suicide attempt. Among the 1.1 million adults who attempted suicide in the past year, 0.9 million reported making suicide plans, and 0.2 million did not make suicide plans. Nearly one third of adults who had serious thoughts of suicide made suicide plans, and about 1 in 9 adults who had serious thoughts of suicide made a suicide attempt. In other words, more than two thirds of adults in 2014 who had serious thoughts of suicide did not make suicide plans, and 8 out of 9 adults who had serious thoughts of suicide did not attempt suicide. This data show that suicidal thoughts can serve as an indicator of suicidal plans and attempts. [122]

Purpose of suicide

Determine what the patient believes his or her suicide would achieve. This suggests how seriously the person has been considering suicide and the reason for death. For example, some believe that their suicide would provide a way for family or friends to realize their emotional distress. Others see their death as relief from their own psychic pain. Still others believe that their death would provide a heavenly reunion with a departed loved one. In any scenario, the clinician has another gauge of the seriousness of the planning.

Potential for homicide

Any question of suicide also must be coupled with an inquiry into the person's potential for homicide. Suicide is often thought to represent aggression turned inward, whereas homicide represents aggression turned outward. Because suicide constitutes an aggressive act, the question regarding homicidal tendencies must be asked.