Practice Essentials

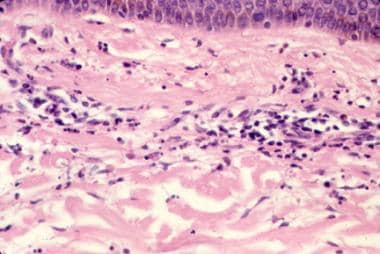

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV), also known as hypersensitivity vasculitis and hypersensitivity angiitis, is a histopathologic term commonly used to denote a small-vessel vasculitis (see the image below). [1, 2] Histologically, LCV is characterized by leukocytoclasis, which refers to vascular damage caused by nuclear debris from infiltrating neutrophils. LCV classically presents as palpable purpura. Less common clinical findings include urticarial plaques, vesicles, bullae, and pustules.

LCV may be secondary to medications, underlying infection, collagen-vascular disorders, or malignancy. [3] Cases of LCV have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination. [4, 5] However, approximately half of cases are idiopathic. [6, 7]

LCV may be localized to the skin or may be associated with systemic involvement. [8] Internal disease most often manifests in the joints, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and the kidneys.

In the absence of internal involvement, the prognosis is excellent, with the majority of cases resolving within weeks to months. Approximately 10% of patients will have chronic or recurrent disease. [9]

LCV may be acute or chronic. Patients with chronic disease may experience persistent lesions or intermittent recurrence. Cases that primarily involve the skin should be treated with nontoxic modalities whenever possible, avoiding the use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), a specific subtype of LCV warranting separate discussion, is characterized by predominant IgA-mediated vessel injury. [10] The classic clinical findings of palpable purpura in HSP are often preceded by viral respiratory illness. HSP is more common in children, but can also occur in adults. Children may develop systemic disease with GI, joint, and/or kidney involvement. In adults, arthritis and kidney disease occur more frequently. [11] HSP in adults, especially older men, may be associated with malignancy. [12]

For additional information on HSP, see Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

For additional information on cutaneous manifestations of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, see Hypersensitivity Vasculitis (Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis).

Pathophysiology

Immune complex deposition, with resultant neutrophil chemotaxis and release of proteolytic enzymes and free oxygen radicals, is a key component in the pathophysiology of LCV. [13, 14] In addition, other autoantibodies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA); inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor alpha; and enhanced expression of vascular adhesion molecules may play a role. [15] However, the exact mechanisms remain unknown.

Etiology

Between one third and one half of LCV cases are idiopathic. The remainder have various identifiable causes, including drugs; infections; food or food additives; and collagen-vascular diseases, malignancies, and other diseases.

The most common drugs that cause LCV are antibiotics, particularly beta-lactam drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and diuretics. However, almost all drugs are potential causes. Foreign proteins such as streptokinase, those found in vaccines, [16] and those used in monoclonal antibody therapy can be associated with a serum sickness syndrome with LCV.

LCV has been reported in users of cocaine adulterated with levamisole, a veterinary anthelminthic drug that was withdrawn from human use because of adverse effects including vasculitis but is found in as much as 70% of cocaine in the United States. [17] Although most cases of levamisole-induced LCV are associated with high titers of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), ANCA-negative vasculitis also occurs in levamisole-adulterated cocaine. [18]

Infections that may be associated with vasculitis include the following:

-

Upper respiratory tract infections, particularly with beta-hemolytic streptococci, and viral hepatitis are implicated most often

-

HIV infection is also associated with some cases of LCV; in addtion, LCV has been posited as an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) related to antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection [19]

-

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be seen with bacterial endocarditis

-

Hepatitis C is a commonly recognized cause of LCV, likely through the presence of cryoglobulins. [20]

When LCV develops in a patient who has received pharmacologic treatment for an infection (eg, antibiotics for an upper respiratory tract infection), determining whether the infection or the drug is responsible for the LCV may be impossible.

Collagen-vascular diseases account for 10-15% of LCV cases. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus may have an associated vasculitis. In many cases, the presence of vasculitis denotes active disease.

Inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn disease [21] may be associated with LCV.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be associated with underlying malignancy and may behave as a paraneoplastic syndrome. [22] Lymphoproliferative diseases, such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, [23] multiple myeloma, and hairy cell leukemia, may be more common culprits. However, any type of tumor at any site may be related to LCV.

A study analyzing 421 adult cases of LCV found that 16 patients (3.8%) had an underlying malignancy, including nine hematologic malignancies and seven solid-organ malignancies. The most common presenting sign was palpable purpura, which preceded the diagnosis of malignancy by an average of 17 days. Paraneoplastic LCV was found more commonly in older patients with constitutional symptoms and in those with anemia and immature cells on peripheral smears. [9]

Effective treatment of the malignancy has led to an apparent cure of the vasculitis in some patients.

Cutaneous vasculitis may be part of a larger-vessel vasculitis such as the following [24] :

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis )

-

Microscopic polyarteritis

-

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome )

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

The incidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis is unknown, but the disorder is presumed to be uncommon.

International

Several studies on leukocytoclastic vasculitis have been conducted in Spain. [25, 26, 27] Hypersensitivity vasculitis (see first image below) occurs in 10-30 persons per million persons per year. Fourteen cases of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (see second image below) per million persons per year have been reported.

Race-, sex-, and age-related differences in incidence

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is reported more often in whites than in other races.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis affects men and women in approximately equal proportions. Some studies from Spain suggest that LCV may be slightly more common in men than in women.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may occur at any age. Henoch-Schönlein purpura is more common in children under 10 years of age.

Prognosis

The prognosis in patients with cutaneous vasculitis depends on the underlying syndrome or the presence of end-organ dysfunction. [28] Patients with disease that primarily affects the skin, joints, or both have a good prognosis. [29] If the kidneys, GI tract, lungs, heart, or central nervous system are involved, morbidity may increase and mortality can occur.

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis), polyarteritis nodosa, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), or severe necrotizing vasculitis have potentially fatal disease. Treatment with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents is often lifesaving.

Cutaneous lesions of LCV are often asymptomatic, but may be associated with pruritus or pain.

Bullous lesions, as well as chronic cutaneous disease, may involve ulceration or painful episodes of purpura, which may cause physical limitations.

-

Hypersensitivity vasculitis.

-

Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

-

Histopathology of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

-

Urticarial vasculitis. Lesions differ from routine urticaria (hives) in that they last longer (often >24 h), are less pruritic, and often resolve with a bruise or residual pigmentation.

-

Erythema elevatum diutinum, a rare cutaneous vasculitis.