Practice Essentials

Renal papillary necrosis (RPN) is kidney damage characterized by coagulative necrosis of the renal medullary pyramids and papillae, brought on by several associated conditions and toxins that exhibit synergism toward the development of ischemia. [1] The clinical course of renal papillary necrosis varies depending on the degree of vascular impairment, the presence of associated causal factors, the overall health of the patient, the presence of bilateral involvement, and, specifically, the number of affected papillae.

Renal papillary necrosis can lead to secondary infection of desquamated necrotic foci, deposition of calculi, and/or separation and eventual sloughing of papillae, with impending acute urinary tract obstruction. Multiple sloughed papillae can obstruct their respective calyces or can congregate and embolize to more distal sites (eg, ureteropelvic junction, ureter, ureterovesical junction). Previously undiagnosed congenital anomalies (eg, partial ureteropelvic junction obstruction) can provide a narrowed area where the sloughed papilla can nest and obstruct.

Renal papillary necrosis is potentially disastrous and, in the presence of bilateral involvement or an obstructed solitary kidney, may lead to renal failure. The infectious sequelae of renal papillary necrosis are more serious if the patient has multiple medical problems, particularly diabetes mellitus.

Background

In 1877, Friedrich first described renal papillary necrosis in a patient with urinary obstruction resulting from hypertrophy of the prostate. [2] Later, Gunther [3] and Edmondson et al [4] described renal papillary necrosis as a lesion associated with diabetes. Since then, researchers have reported that 17-90% of all patients with renal papillary necrosis have diabetes and that 25-73% of patients have severe urinary tract obstructions. In 1945, Spuhler and Zollinger documented the first description of analgesic nephropathy. [5] Since then, analgesic abuse has been increasingly significant in the development of papillary necrosis, particularly in Australia, England, and Scandinavia.

The first description of papillary necrosis recorded in the literature is Johann Wagner's 1827 report of Ludwig van Beethoven's autopsy. The original autopsy protocol by Wagner, which was written in Latin, was translated into German by von Seyfried in 1832 and has only recently been rediscovered. [6]

Reports indicate that Beethoven, the highly regarded musical genius and among the best composers of all time, was a long-term abuser of alcohol and analgesics. Beethoven was prone to headaches, back pain, and attacks of rheumatism or gout. His physician often prescribed salicin, a commonly used analgesic substance at that time, which was made from dried and powdered willow bark. His alcohol abuse was compounded by a viral hepatitis that led to liver cirrhosis and chronic pancreatitis. Davies postulated that Beethoven developed diabetes mellitus secondary to chronic pancreatitis. [7] Beethoven had no reported history of urinary obstruction, nor was it mentioned in his autopsy report.

Wagner reported "calcareous concretions" filling every calyx of both kidneys. He described the concretions as "symmetrical and soft like a pea cut across the middle." According to Davies and Schwarz, this finding is so typical of renal papillary necrosis that the diagnosis is as near to certain as possible without a histologic examination. [7, 8]

Researchers postulate that Beethoven's renal papillary necrosis was most likely a consequence of analgesic abuse and decompensated liver cirrhosis, which ultimately caused his death. [9] Davies contests that Beethoven also had diabetes and that this illness was the primary risk factor for him developing renal papillary necrosis. Indeed, all 3 conditions may have been synergistic factors.

Problem

Renal papillary necrosis is sometimes classified as one end of a spectrum of changes associated with pyelonephritis and tubulointerstitial nephritis. Renal papillary necrosis is often considered a complication or extension of severe pyelonephritis that is more devastating than usual because of associated disease states, particularly diabetes and urinary tract obstructions. Other sources believe this consideration is inaccurate and archaic because renal papillary necrosis does not usually occur with florid pyelonephritis.

Indeed, pyelonephritis and an ascending urinary tract infection are conditions that are commonly associated with renal papillary necrosis. Infection is a frequent and important finding in most cases, contributing significantly to the clinical presentation of renal papillary necrosis (ie, fever and chills in approximately two thirds of patients, positive urine culture results in 70%). However, renal papillary necrosis can occur in the absence of infection, indicating that infection may not be the primary process in the pathogenesis. It is likely that infection is a complication of renal papillary necrosis; the necrotic papillae act as a nidus for infection and lithogenesis. Infection within necrotic material and calculi is often difficult to definitively treat with antibiotics alone, and infection often recurs as renal papillary necrosis progresses to chronic pyelonephritis.

Renal papillary necrosis is considered a sequela of ischemia occurring in the renal papillae and the medulla, which can result from a variety of causes. In the setting of infection, the boggy inflammatory interstitium of the pyelonephritic kidney compresses the medullary vasculature and, thus, predisposes the patient to ischemia and renal papillary necrosis. This vasculature can become compressed, attenuated, or impaired from several other associated diseases, most notably diabetes mellitus, urinary tract obstruction, and analgesic nephropathy. Therefore, renal papillary necrosis is a distinct clinical and pathophysiological entity primarily caused by ischemia that can develop without pyelonephritis or urinary tract infection and is likely a focus for infectious complications. Renal papillary necrosis has a well-documented association with several diseases that predispose a patient to ischemia.

Renal papillary necrosis can be a unilateral or a bilateral process, depending on the etiology. Physicians diagnose true unilateral renal papillary necrosis when the predisposing factor is infection or obstruction that is limited to one kidney, as is the scenario in a patient with congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction. For systemic causes (eg, diabetes mellitus, analgesic nephropathy) a bilateral procees is to be expected, considering the systemic nature of the associated diseases and the ischemic pathophysiologic mechanism of renal papillary necrosis. Reports indicate that, among patients in whom a single kidney is involved at initial presentation, renal papillary necrosis will develop in the contralateral kidney within 4 years.

Significant contributions aimed at improving the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of renal papillary necrosis include preliminary studies by Falkenberg et al, who investigated monoclonal antibodies that may provide direct diagnostic access to the renal papilla and may allow for early detection of papillary damage. [10] Monoclonal antibodies specific for papillary antigens have been used to detect these antigens in urine following toxic insults to the kidney. Further work has been performed by Price et al in which renal papillary antigen 1 (RPA-1) has been demonstrated to be an excellent marker of renal papillary necrosis that can be used to detect this toxicity in preclinical safety testing. [11]

Studies by Garber et al have revealed that the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril has a protective and therapeutic effect in rats with bromoethylamine-induced renal papillary necrosis, which is characterized by marked interstitial fibrosis, impressive decreases in the glomerular filtration rate, and albuminuria. [12] Histologic examination of rats treated with enalapril reveals a 67-88% decrease in renal papillary necrosis. These studies also demonstrate renoprotective effects of enalapril, including a significant improvement in the glomerular filtration rate and elimination of albuminuria.

A report from Abe et al described the treatment of renal papillary necrosis in a patient with diabetes. [13] Prostaglandin E1 was infused intravenously at a dose of 40 mg/d for 14 days. This attempt at improving renal circulation increased both creatinine clearance and renal plasma flow, with a concomitant decrease in proteinuria. Vasodilatory agents such as prostaglandin E1 may improve renal circulation and hemodynamics and should be considered as possible therapy for renal papillary necrosis, particularly in patients with diabetes.

Relevant Anatomy

Briefly reviewing basic renal anatomy and histology allows a clear understanding of the pathophysiology of the underlying ischemia of renal papillary necrosis and how this ischemia is distributed.

The renal papilla is the rounded apex of each medullary pyramid and represents the confluence of the collecting ducts from each nephron within that pyramid. An individual minor calyx cups each papilla; these calyces represent the most proximal aspect of the renal collecting system and are lined with transitional cells.

The renal papillary blood supply is derived from 2 sources: the vasa rectae, which disperse blood from the efferent arteriole, and the interlobar branches of the renal artery, which run within the adventitia of the minor calyces. The vasa rectae arise from the efferent arteriole within the renal cortex and form wide and plentiful vascular bundles at the base of the medullary pyramid. The bundles taper as they continue distally toward the apex and papilla. This process results in the papillary tip receiving only a marginal supply of blood, which appears to be a predisposing factor for the central role of ischemia in the development of renal papillary necrosis.

The already tenuous vasculature is further impaired by several pathophysiologic states, including the above-described boggy inflammatory interstitium of pyelonephritis, the microangiopathy of diabetes mellitus, the increased pyelovenous pressure of urinary obstruction, the chronic hyperbilirubinemia of liver cirrhosis, the oxidative damage of analgesic nephropathy, and the intraluminal stasis of sickle cell disease.

Pathophysiology

Renal papillary necrosis is classified as focal (ie, involving only the tip of the papilla) or diffuse (ie, involving the whole papilla and areas of the medulla), depending primarily on the patient's degree of impaired vasculature. Renal papillary necrosis may simply affect a single papilla, or the entire kidney may be grossly involved. Once again, renal papillary necrosis is more often a bilateral process; many of the predisposing factors are systemic. Renal papillary necrosis never involves the entire medulla; the disease is always strictly limited to the inner, more distal zone of the medulla and the papilla.

Researchers recognize 2 pathologic forms of renal papillary necrosis—the medullary form and the papillary form. The pathogenic form is dictated by the degree of vascular impairment. The medullary form is characterized by intact fornices, discrete grain-sized necrotic areas, and later defects in the papillae. Clinicians often observe sinus tracts extruding from irregular medullary cavities. In the papillary form, the calyceal fornices and the entire papillary surface are destroyed, demarcated, and sequestered. If these fornices and papillary surfaces are not sloughed, they reepithelialize and acquire a smoother appearance.

Patients with medullary ischemia develop decreased glomerular filtration rates, salt wasting, an impaired ability to concentrate, and polyuria because the vasa rectae supply the medulla and serve the countercurrent exchange mechanism.

The pathologic findings on a cut section include gray-white to yellow necrosis that resembles infection on the tips or distal two thirds of the pyramids. Microscopically, the tissue shows characteristic coagulative infarct necrosis, with preserved tubule outlines. The leukocytic response is limited to the junctions between preserved and destroyed tissue. After the acute phase, scars that can be observed on the cortical surface as fibrous depressions replace the inflammatory foci. This pyelonephritic scar is usually associated with inflammation, fibrosis, and a deformation of the underlying calyces and pelvis.

Papillary necrosis is easily induced experimentally by administering a combination of aspirin and phenacetin, usually to subjects in a water-depleted state. The phenacetin metabolite p-phenetidin exhibits high renal toxicity; it injures cells by covalent binding and oxidative damage. These papillotoxins target interstitial cells via hydroperoxidase-mediated activation. Aspirin induces its potentiating effect by inhibiting the vasodilatory effects of prostaglandin, thus predisposing the papilla to ischemia. Therefore, papillary damage may be the result of a combination of the direct toxic effects of phenacetin metabolites and ischemic injury to both tubular cells and vessels. Grossly, the cortex exhibits depressed areas that represent cortical atrophy overlying the raised necrotic papillae. The papillae within the kidney show various stages of necrosis with calcification, fragmentation, desquamation, and sloughing.

This development contrasts with the papillary necrosis observed in patients with diabetes, whose papillae are generally at the same stage of acute necrosis at any given time. Microscopically, the individual papillary changes range from a patchy appearance to the advanced form, wherein the entire papilla is necrotic. When the papillae remain attached, they are structureless masses with ghosts of tubules and foci of dystrophic calcification. These tubules and calcifications subsequently fragment and slough, becoming potential obstructive entities. The cortical columns of Bertin that contain the glomeruli characteristically remain uninvolved. Certain papillotoxins target interstitial cells, resulting in hydroperoxidase-mediated activation with subsequent inflammatory, degradative, and necrotic cell changes.

Etiology

Generally, any condition associated with ischemia predisposes an individual to papillary necrosis. Important general considerations include shock, massive fluid sequestration (eg, as in pancreatitis), dehydration, hypovolemia, and hypoxia. Certain conditions have a known association with renal papillary necrosis, and the underlying mechanism of these conditions is ischemia, which ultimately leads to renal papillary necrosis.

A useful mnemonic device for the conditions associated with renal papillary necrosis is POSTCARDS, which stands for the following:

-

Obstruction of the urinary tract

-

Sickle cell hemoglobinopathies, including sickle cell trait

-

Tuberculosis

-

Cirrhosis of the liver, chronic alcoholism

-

Analgesic abuse

-

Renal transplant rejection, radiation

-

Systemic vasculitis

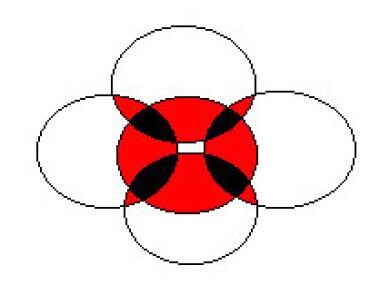

More than half the patients with renal papillary necrosis have 2 or more of these causative factors. Thus, renal papillary necrosis in most patients is multifactorial in origin, and physicians must consider the pathogenesis of renal papillary necrosis a combination of detrimental factors that overlap and operate in concert to cause renal papillary necrosis (see image below).

In this figure, the multifactorial nature of renal papillary necrosis is represented by 5 of the disease's most frequently associated conditions: infection, obstruction, diabetes mellitus, analgesic abuse, and sickle cell disease. Each circle represents a condition. Note how the conditions overlap; the red areas show the coexistence of 2 conditions, and the black areas represent 3 coexistent conditions. Multiple conditions exhibit synergism and, therefore, worsen both the severity of the disease and the prognosis.

In this figure, the multifactorial nature of renal papillary necrosis is represented by 5 of the disease's most frequently associated conditions: infection, obstruction, diabetes mellitus, analgesic abuse, and sickle cell disease. Each circle represents a condition. Note how the conditions overlap; the red areas show the coexistence of 2 conditions, and the black areas represent 3 coexistent conditions. Multiple conditions exhibit synergism and, therefore, worsen both the severity of the disease and the prognosis.

One of the most common and most preventable etiologic factors is the use of analgesics. A classic factor is phenacetin, with its highly toxic metabolite, p-phenetidin. More recently, however, the rising popularity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly those that inhibit cyclooxygenases (ie, COX-1, COX-2) has led to a relatively high frequency of adverse events in patients at risk for renal papillary necrosis.

In healthy individuals in whom renal arterial blood flow is not compromised, NSAIDs have little effect unless they are used in excess. This is mostly true because the kidney is not relying on the vasodilatory effects of prostaglandin to supply adequate perfusion. However, in patients who are predisposed to renal hypoperfusion, local prostaglandin synthesis protects the glomeruli and tubules from ischemia. The inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by NSAIDs that inhibit COX-1 and/or COX-2 removes this protective mechanism and predisposes the kidney to further renal hypoperfusion and, ultimately, ischemia. An extremely important precaution is to strictly monitor patients with prior kidney disease or any of the above-mentioned etiologic conditions when prescribing NSAIDs.

Additionally, note that a short course of NSAIDs has caused papillary necrosis and nonoliguric renal failure in otherwise healthy individuals as young as age 17 years. A case such as this may be an anomaly, but caution is warranted when prescribing NSAIDs. Patients should maintain adequate hydration and avoid physiologic stress while on these medications.

Multiple publications have described indinavir-induced renal papillary necrosis. In one study, diagnosis was delayed as the initial symptoms were attributed to suspected urinary tuberculosis. These studies demonstrate the necessity of renal function monitoring during HIV treatment above that of calculus monitoring. [14, 15]

A case of RPN associated with aspergillosis has been reported in a 35-year old immunocompetent man with no comorbidities. [16]

Epidemiology

Frequency

Renal papillary necrosis generally affects individuals who are in the middle decades of life or older. The typical patient is aged 53 years, with nearly half of cases occurring in individuals older than 60 years and more than 90% of cases occurring in individuals older than 40 years. Renal papillary necrosis is uncommon in individuals younger than 40 years and in the pediatric population, except in patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies, hypoxia, dehydration, and septicemia.

In general, renal papillary necrosis is more common in women than in men. Mandel organized the first comprehensive review to focus attention on renal papillary necrosis. [17] In his series, which examined 160 cases of renal papillary necrosis from the world literature, 96 patients (60%) had diabetes mellitus, 48 patients (30%) had urinary tract obstruction, and 15 patients (9.4%) had both. In the group with diabetes, women outnumbered men, and in the group of patients without diabetes, men outnumbered women, further reflecting the frequency and significance of urinary tract obstructions in elderly men with renal papillary necrosis. An autopsy report from 1957 by Simon and associates documented the presence of acute or chronic pyelonephritis in 95%. [18]

Analgesic nephropathy, another associated condition and causal factor of renal papillary necrosis, is also more common in women than in men. Analgesic nephropathy is particularly prevalent in individuals with recurrent headaches or chronic, unremitting muscle and joint pain and in patients with psychoneuroses.

Occupational risks are not associated with developing renal papillary necrosis.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with renal papillary necrosis depends on the etiology of the ischemic insult, the number of associated pathologic factors, the dispersal of the necrosis, the involvement of one or both kidneys, and the overall health of the patient. Elderly debilitated patients with multiple medical problems have a poor prognosis, as do patients with overwhelming sepsis and multiple comorbidities. The prognosis is generally worse in patients with diabetes, specifically those who are not compliant and who are prone to severe episodes of hyperglycemia.

Considering the synergistic nature of its predisposing factors, papillary necrosis may be avoided by controlling chronic diseases such as sickle cell disease, diabetes, and cirrhosis. Patients with such conditions should be careful to avoid excessive use of analgesics that are known to be associated with papillary necrosis. Patients who use such analgesics should be screened for signs and symptoms of urinary tract infections and/or urinary obstruction and treated accordingly.

When papillary necrosis arises unexpectedly (ie, in a patient with sepsis), the treatment focus should be as follows:

-

Prevent urinary tract infections (eg, by avoiding unnecessary use of indwelling catheters)

-

Maintain adequate hydration and homeostasis

-

Avoid analgesics and other nephrotoxic medications

-

Maintain tight glycemic control in patients with diabetes

-

In this figure, the multifactorial nature of renal papillary necrosis is represented by 5 of the disease's most frequently associated conditions: infection, obstruction, diabetes mellitus, analgesic abuse, and sickle cell disease. Each circle represents a condition. Note how the conditions overlap; the red areas show the coexistence of 2 conditions, and the black areas represent 3 coexistent conditions. Multiple conditions exhibit synergism and, therefore, worsen both the severity of the disease and the prognosis.

-

Cystoscopic photograph of sloughed papilla extruding from the ureteral orifice. The patient was a 51-year-old man with poorly controlled diabetes and a history of microhematuria and an acute onset of severe left flank pain. Findings of upper tract imaging with a renal ultrasonography and intravenous pyelography were remarkable only for mixed heterogeneity consistent with medical renal disease. Urine cytology results were negative, and culture showed no growth. In-office flexible cystoscopy revealed the mass extruding from the left ureteral orifice, which required sedation and rigid cystoscopy to extract. Gross examination yielded a tan, friable, irregular, wedge-shaped soft tissue mass 1.7 cm X 1.6 cm X 1.5 cm. Bilateral retrograde pyelography revealed a clubbed left upper pole calyx and no other filling defects. The pathology was necrotic epithelial tissue.