Practice Essentials

Fournier gangrene was first identified in 1883, when the French venereologist Jean Alfred Fournier described a series in which 5 previously healthy young men suffered from a rapidly progressive gangrene of the penis and scrotum without apparent cause. This condition, which came to be known as Fournier gangrene, is defined as a polymicrobial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineal, perianal, or genital areas (see the image below.)

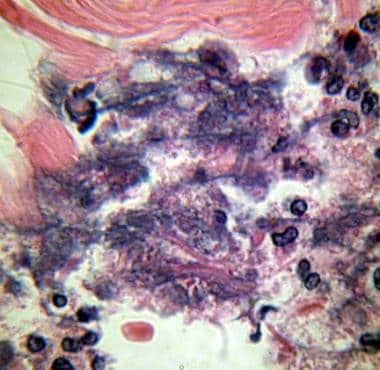

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000X magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000X magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

In contrast to Fournier's initial description, the disease is not limited to young people or to males, and a cause is now usually identified. [1, 2] Impaired immunity (eg, from diabetes) is known to increase susceptibility to Fournier gangrene. Trauma to the genitalia, which can cause a breach in the integrity of epithelial or urethral mucosa, is a frequently recognized mechanism by which bacteria are introduced, subsequently initiating the infectious process. [3, 4, 5] For more information, see the following Medscape articles:

Early, aggressive intervention is critical, as the condition is associated with a high mortality rate. Surgery is necessary for definitive diagnosis and excision of necrotic tissue. Along with debridement, surgical procedures may include complex closure, suprapubic tube placement, and fecal diversion. [6] Early administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics is indicated. Finally, any underlying comorbid conditions must ultimately be addressed. See Treatment and Medication.

Background

In 1764, Baurienne originally described an idiopathic, rapidly progressive soft-tissue necrotizing process that led to gangrene of the male genitalia. However, the disease was named after Jean-Alfred Fournier, a Parisian venereologist, on the basis of a transcript from an 1883 clinical lecture in which Fournier presented a case of perineal gangrene in an otherwise healthy young man, adding this to a compiled series of 4 additional cases. [7] He differentiated these cases from perineal gangrene associated with diabetes, alcoholism, or known urogenital trauma, although these are currently recognized risk factors for the perineal gangrene now associated with his name.

This manuscript outlining Fournier’s initial series of fulminant perineal gangrene provides a fascinating insight into both the societal background and the practice of medicine at the time. In anecdotes, Fournier described recognized causes of perineal gangrene, including placement of a mistress’ ring around the phallus, ligation of the prepuce (used in an attempt to control enuresis or as an attempted birth control technique practiced by an adulterous man to avoid impregnating his married lover), placement of foreign bodies such as beans within the urethra, and excessive intercourse in diabetic and alcoholic persons. He calls upon physicians to be steadfast in obtaining confession from patients of “obscene practices.”

Anatomy

The complex anatomy of the male external genitalia influences the initiation and progression of Fournier gangrene. This infectious process involves the superficial and deep fascial planes of the genitalia. As the microorganisms responsible for the infection multiply, infection spreads along the anatomical fascial planes, often sparing the deep muscular structures and, to variable degrees, the overlying skin, making the extent of involvement difficult to appreciate.

This phenomenon has implications for both initial debridement and subsequent reconstruction. Therefore, a working knowledge of the anatomy of the male lower urinary tract and external genitalia is critical for the clinician treating a patient with Fournier gangrene.

Skin and superficial fascia

Because Fournier gangrene is predominately an infectious process of the superficial and deep fascial planes, understanding the anatomic relationship of the skin and subcutaneous structures of the perineum and abdominal wall is important.

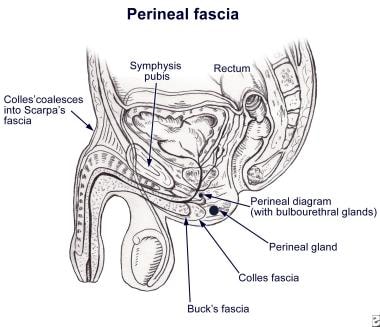

The skin cephalad to the inguinal ligament is backed by Camper fascia, which is a layer of fat-containing tissue of varying thickness and the superficial vessels to the skin that run through it. Scarpa fascia forms another distinct layer deep to Camper fascia. In the perineum, Scarpa fascia blends into Colles fascia (also known as the superficial perineal fascia), while it is continuous with Dartos fascia of the penis and scrotum (see the image below).

Fascial envelopment of the perineum (male). Note how Colles fascia completely envelops the scrotum and penis. Colles fascia is in continuity cephalad to the level of the clavicles. In the inguinal region, this fascial layer is known as Scarpa fascia. Familiarity with this fascial anatomy, along with recognition that necrotizing fasciitis tends to spread along fascial planes, makes it easy to understand how a process that starts in the perineum can spread to the abdominal wall, the flank, and even the chest wall.

Fascial envelopment of the perineum (male). Note how Colles fascia completely envelops the scrotum and penis. Colles fascia is in continuity cephalad to the level of the clavicles. In the inguinal region, this fascial layer is known as Scarpa fascia. Familiarity with this fascial anatomy, along with recognition that necrotizing fasciitis tends to spread along fascial planes, makes it easy to understand how a process that starts in the perineum can spread to the abdominal wall, the flank, and even the chest wall.

Several important anatomic relationships should be considered. A potential space between the Scarpa fascia and the deep fascia of the anterior wall (external abdominal oblique) allows for the extension of a perineal infection into the anterior abdominal wall. Superiorly, Scarpa and Camper fascia coalesce and attach to the clavicles, ultimately limiting the cephalad extension of an infection that may have originated in the perineum.

Colles fascia is attached to the pubic arch and the base of the perineal membrane, and is continuous with the superficial Dartos fascia of the scrotal wall. The perineal membrane is also known as the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm and, together with Colles fascia, defines the superficial perineal space.

This space contains the membranous urethra, bulbar urethra, and bulbourethral glands. In addition, this space is adjacent to the anterior anal wall and ischiorectal fossae. Infectious disease of the male urethra, bulbourethral glands, perineal structures, or rectum can drain into the superficial perineal space and can extend into the scrotum or into the anterior abdominal wall up to the level of the clavicles.

Vascular supply to the skin of the lower abdomen and genitalia

Branches from the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries supply the lower aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. Branches of the external and internal pudendal arteries supply the scrotal wall. With the exception of the internal pudendal artery, each of these vessels travels within Camper fascia and can therefore become thrombosed in the progression of Fournier gangrene.

Thrombosis jeopardizes the viability of the skin of the anterior scrotum and perineum. Since the internal pudendal artery is not contained within Camper fascia, it is less susceptible to thrombosis; therefore, its vascular territory—the posterior aspect of the scrotal wall—remains viable and can be used in the reconstruction following resolution of the infection.

Penis and scrotum

The contents of the scrotum, namely the testicles, epididymides, and cord structures, are invested by several fascial layers distinct from the Dartos fascia of the scrotal wall. Again, several important anatomic relationships should be considered.

The most superficial layer of the testis and cord is the external spermatic fascia, which is continuous with the external aponeurosis of the superficial inguinal ring (external abdominal oblique). The next deeper layer is the internal spermatic fascia, which is continuous with the transversalis fascia. A deep fascia termed Buck fascia covers the erectile bodies of the penis, the corpora cavernosa, and the anterior urethra. Buck fascia fuses to the dense tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa, deep in the pelvis.

The fascial layers described in this section do not become involved with an infection of the superficial perineal space and can limit the depth of tissue destruction in a necrotizing infection of the genitalia. The corpora cavernosa, urethra, testes, and cord structures are usually spared in Fournier gangrene, while the superficial and deep fascia and the skin are destroyed.

Pathophysiology

Localized infection adjacent to a portal of entry is the inciting event in the development of Fournier gangrene. Ultimately, an obliterative endarteritis develops, and the ensuing cutaneous and subcutaneous vascular necrosis leads to localized ischemia and further bacterial proliferation. Rates of fascial destruction as high as 2-3 cm/h have been described.

Infection of superficial perineal fascia (Colles fascia) may spread to the penis and scrotum via Buck and Dartos fascia, or to the anterior abdominal wall via Scarpa fascia, or vice versa. Colles fascia is attached to the perineal body and urogenital diaphragm posteriorly and to the pubic rami laterally, thus limiting progression in these directions. Testicular involvement is rare, as the testicular arteries originate directly from the aorta and thus have a blood supply separate from the affected region. Far-advanced or fulminant Fournier gangrene can spread from the fascial envelopment of the genitalia throughout the perineum, along the torso, and, occasionally, into the thighs.

The following are pathognomonic findings of Fournier gangrene upon pathologic evaluation of involved tissue:

-

Necrosis of the superficial and deep fascial planes<

-

Fibrinoid coagulation of the nutrient arterioles

-

Polymorphonuclear cell infiltration

-

Microorganisms identified within the involved tissues

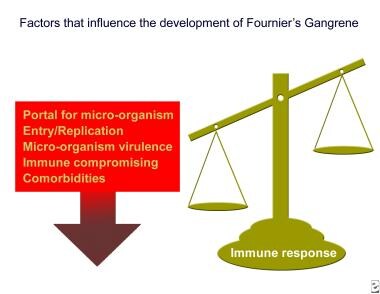

Infection represents an imbalance between (1) host immunity, which is frequently compromised by one or more comorbid systemic processes, and (2) the virulence of the causative microorganisms. The etiologic factors allow the portal for entry of the microorganism into the perineum; the compromised immunity provides a favorable environment to initiate the infection; and the virulence of the microorganism promotes the rapid spread of the disease. See the image below.

Necrotizing infection results when the pathogen is extremely virulent or, most commonly, when a combination of microorganisms act synergistically in a susceptible immunocompromised host.

Necrotizing infection results when the pathogen is extremely virulent or, most commonly, when a combination of microorganisms act synergistically in a susceptible immunocompromised host.

Microorganism virulence results from the production of toxins or enzymes that create an environment conducive to rapid microbial multiplication. [8] Although Meleney in 1924 attributed the necrotizing infections to streptococcal species only, [9] subsequent clinical series have emphasized the multiorganism nature of most cases of necrotizing infection, including Fournier gangrene. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Presently, recovering only streptococcal species is unusual. [15] Rather, streptococcal organisms are cultured along with as many as 5 other organisms.

The following are common causative microorganisms:

-

Streptococcal species

-

Staphylococcal species

-

Enterobacteriaceae

-

Anaerobic organisms

-

Fungi

Most authorities believe that polymicrobial involvement is necessary to create the synergy of enzyme production that promotes rapid multiplication and spread of Fournier gangrene. [8] For example, one microorganism might produce the enzymes necessary to cause coagulation of the nutrient vessels. Thrombosis of these nutrient vessels reduces local blood supply; thus, tissue oxygen tension falls.

The resultant tissue hypoxia allows for the growth of facultative anaerobes and microaerophilic organisms. These latter microorganisms, in turn, may produce enzymes (eg, lecithinase, collagenase), which lead to digestion of fascial barriers, thus fueling the rapid extension of the infection.

Fascial necrosis and digestion are hallmarks of this disease process; this is important to appreciate because it provides the surgeon with a clinical marker of the extent of tissue involvement. Specifically, if the fascial plane can be separated easily from the surrounding tissue by blunt dissection, it is quite likely to be involved with the ischemic-infectious process; therefore, any such dissected tissue should be excised.

Etiology

Although originally described as idiopathic gangrene of the genitalia, Fournier gangrene has an identifiable cause in 75-95% of cases. [16] The necrotizing process commonly originates from an infection in the anorectum, the urogenital tract, or the skin of the genitalia. [17]

Anorectal causes of Fournier gangrene include perianal, perirectal, and ischiorectal abscesses; anal fissures; anal fistula; and colonic perforations. These may be a consequence of colorectal injury or a complication of colorectal malignancy, [18, 19] inflammatory bowel disease, [20] colonic diverticulitis, or appendicitis.

A case of Fournier gangrene was reported in a patient with COVID-19 following prolonged and repeated ventilation in prone position. [21]

Urogenital tract causes include the following:

-

Infection in the bulbourethral glands

-

Urethral injury

-

Iatrogenic injury secondary to urethral stricture manipulation

-

Epididymitis

-

Orchitis

-

Lower urinary tract infection (eg, in patients with long-term indwelling urethral catheters)

Dermatologic causes include hidradenitis suppurativa, ulceration due to scrotal pressure, and trauma. Inability to practice adequate perineal hygiene, such as in paraplegic patients, results in increased risk.

Accidental, intentional, or surgical trauma [22] and the presence of foreign bodies may also lead to the disease. The following have been reported in the literature as precipitating factors:

-

Blunt thoracic trauma

-

Superficial soft-tissue injuries

-

Genital piercings

-

Penile self-injection with cocaine [23]

-

Urethral instrumentation

-

Prosthetic penile implants

-

Intramuscular injections

-

Steroid enemas (used for the treatment of radiation proctitis)

-

Rectal foreign body [24]

In women, septic abortions, vulvar or Bartholin gland abscesses, hysterectomy, and episiotomy are documented sources. A comprehensive literature review of 134 women with Fournier gangrene reported that perineal abscess was the most common etiology (n=41, 35%). [2] In men, anal intercourse may increase risk of perineal infection, either from blunt trauma to the area or by spread of rectally carried microbes.

In children, the following have led to the disease:

-

Circumcision

-

Phimosis

-

Strangulated inguinal hernia

-

Omphalitis

-

Insect bites

-

Trauma

-

Urethral instrumentation

-

Prematurity [25]

-

Perirectal abscesses

-

Systemic infections

-

Diaper rash [25]

-

Secondary immunodeficiency

A case report by Numoto et al describes Fournier gangrene that developed after surgical repair of a strangulated inguinal hernia in a 2-month-old boy. The boy was receiving adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) therapy for infantile spasms, and the authors suggest that immune suppression from the ACTH may have contributed to the development of Fournier gangrene. [26]

Pathogens

Wound cultures from patients with Fournier gangrene reveal that it is a polymicrobial infection with an average of 4 isolates per case. Escherichia coli is the predominant aerobe, and Bacteroides is the predominant anaerobe.

Other common microflora include the following:

-

Proteus

-

Staphylococcus

-

Enterococcus

-

Streptococcus (aerobic and anaerobic)

-

Pseudomonas

-

Klebsiella

-

Clostridium [27]

Rarely, Candida albicans has been reported as the pathogen in cases of Fournier gangrene. [28, 29, 30]

Predisposition to disease

Any condition that depresses cellular immunity may predispose a patient to the development of Fournier gangrene. Examples include the following:

-

Morbid obesity

-

Alcoholism

-

Cirrhosis

-

Extremes of age

-

Vascular disease of the pelvis

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus [34]

-

Crohn disease

-

HIV infection [35] ref34}

-

Malnutrition

-

Iatrogenic immunosuppression (eg, from long-term corticosteroid therapy or chemotherapy [36] )

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has noted an increased risk for Fournier gangrene in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. SGLT2 inhibitors were first approved in 2013, and by 2019, 55 cases of Fournier gangrene had been reported in patients receiving these agents. By comparison, only 19 cases of Fournier gangrene have been reported over 35 years in patients taking other diabetes drugs. [37]

Details of Fournier gangrene cases associated with SGLT2 inhibitors included the following [37] :

-

Patients ranged in age from 33 to 87 years; 39 were men, 16 were women.

-

Onset of Fournier gangrene after initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors ranged from 5 days to 49 months.

-

Complications included diabetic ketoacidosis, sepsis, and kidney injury.

-

Eight patients underwent fecal diversion surgery, two patients required amputation of a lower extremity due to necrotizing fasciitis, and three patients died.

Epidemiology

Fournier gangrene is relatively uncommon, but the exact incidence of the disease is unknown. In a review of Fournier gangrene in 1992, Paty et al calculated that approximately 500 cases of the infection had been reported in the literature since Fournier’s 1883 report, yielding a rate of 1 case in 7500 persons. [38] A retrospective case review revealed 1726 cases documented in the literature from 1950-1999, with an average of 97 cases per year reported from 1989-1998. [39] A review of National Inpatient Sample data from 2004-2012 identified a total of 9249 patients with Fournier gangrene. [6]

A review using the US State Inpatient Database in 2009 estimated that among 25.8 million hospital admissions from 2001 and 2004, Fournier gangrene constituted only 0.02% of hospital admissions. In this same database, 66% of the hospitals reported no patients with Fournier gangrene, and among high volume centers, the admission frequency was only 1 patient every few months. [40]

The frequency of Fournier gangrene has not likely changed appreciably. Rather, the apparent increase in the number of cases in the literature most likely results from increased reporting.

No seasonal variation occurs. Fournier gangrene is not indigenous to any region of the world, although the largest clinical series originate from the African continent. [41]

Sex- and age-related differences in incidence

The typical patient with Fournier gangrene is an elderly man in his sixth or seventh decade of life with comorbid diseases. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 10:1. The lower incidence in females may reflect better drainage of the perineal region through vaginal secretions. [2]

Men who have sex with men may be at higher risk, especially for infections caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). [42]

Most reported cases occur in patients aged 30-60 years. A literature review found only 56 pediatric cases, with 66% of those in infants younger than 3 months.

Prognosis

Large scrotal, perineal, penile, and abdominal wall skin defects may require reconstructive procedures; however, the prognosis for patients following reconstruction for Fournier gangrene is usually good. The scrotum has a remarkable ability to heal and regenerate once the infection and necrosis have subsided. However, approximately 50% of men with penile involvement have pain with erection, often related to genital scarring. Consultation with a psychiatrist may help some patients deal with the emotional stress of an altered body image.

If extensive soft tissue is lost, lymphatic drainage may be impaired; thus, dependent edema and cellulitis may result. Use of external support may be beneficial to minimize this postoperative problem.

To date, the majority of studies of Fournier gangrene have been retrospective reviews. [43, 44] Therefore, the utility of drawing reliable prognostic information from these studies is very limited.

In 1995, Laor and colleagues introduced the Fournier Gangrene Severity Index (FGSI). [45] The FGSI is based on deviation from reference ranges of the following clinical parameters:

-

Temperature

-

Heart rate

-

Respiratory rate

-

White blood cell count (WBC)

-

Hematocrit

-

Serum sodium

-

Serum potassium

-

Serum creatinine

-

Serum bicarbonate

Each parameter is assigned a score between 0 and 4, with the higher values indicating greater deviation from normal. The FGSI represents the sum of all the parameters’ values.

Laor and colleagues determined that an FGSI greater than 9 correlated with increased mortality. [45] The FGSI has been validated in several retrospective studies. [46, 47, 48] In a retrospective review of 20 patients with Fournier gangrene, the average FGSI was 9 overall and 14 for fatal cases. An increased FGSI was predictive of having an increased mortality rate or hospital stay longer than the median (>25 days) (P=0.0194). [49]

In 2010, Yilmazlar and colleagues updated the FGSI (UFGSI), adding two additional parameters—age and extent of disease—to further refine the prognostic utility of the FGSI. [50]

These two groups concluded that the mortality risk in general may be directly proportional to the age of the patient and the extent of disease burden and systemic toxicity upon admission. Factors associated with an improved prognosis included the following [50, 51, 52] :

-

Age younger than 60 years

-

Localized clinical disease

-

Absence of systemic toxicity (eg, low FGSI)

-

Sterile blood cultures

Most recently, Roghmann et al queried whether these increasingly complex scoring systems actually outperformed two existing and less burdensome morbidity scoring systems, the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (ACCI) and the surgical APGAR score (sAPGAR). [53] They assessed this retrospectively then prospectively with a 30-day follow-up. They noted that ACCI and sAPGAR performed as well as the FGSI and UFGSI and were easier to calculate at the bedside. Again, increasing age and medical comorbidities were associated with increased risk of death. [53]

Bozkurt et al reached a similar conclusion in their comparison of the FGSI; the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC), which is based on the WBC, hemoglobin, serum sodium, glucose, serum creatinine, and C-reactive protein levels; and the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR)—a marker for inflammation that has been studied as a prognostic indicator in a variety of conditions, primarily cancer and heart disease. In their retrospective cohort studies, higher scores in all three scoring systems (FGSI ≥4, LRINEC ≥6, NLR ≥10) identified patients with a worse prognosis, including need for mechanical ventilation requirement and mortality. However, the NLR had the advantages of speed, simplicity, and low cost. [54]

In a retrospective case series that included 19 patients with a median age of 70 years, Morais et al reported that the percentage of body surface area (BSA) affected proved to be a useful prognostic factor. Combining the LRINEC model with a BSA >3.25% led to a major improvement in the accuracy of the scores. [51]

In a retrospective review of 54 patients with a mean age of 49.3 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 28.6 kg/m2, patients on average were hospitalized for 37.5 days, with a mean intensive care unit stay of 8.3 days. Three patients (5.6%) died during their hospital stay, and 33 (61%) required reconstructive surgery. Multivariate logistic modeling showed that BMI (P=0.001) and alkaline phosphatase (P< 0.001) correlated with decreasing length of stay, while age at admission was not significantly correlated (P=0.369). [55]

This study also developed a novel scoring system, the Combined Urology and Plastics Index (CUPI), designed to predict length of stay in Fournier gangrene patients. CUPI parameters include the following:

-

Age at admission

-

Hematocrit

-

Plasma CO 2 (serum bicarbonate)

-

Blood urea nitrogen

-

Serum calcium

-

Alkaline phosphatase

-

Albumin

-

International normalized ratio (INR)

-

Lactate

-

Total bilirubin

The CUPI scoring system has a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 15. Patients with CUPI scores ≤5 had an average length of stay of 25 days (standard deviation [SD], 15.6), while those with CUPI scores >5 had an average length of stay of 71 days (SD 49.8). [55]

Interestingly, obesity is independently associated with reduced in-hospital mortality in patients with severe soft tissue infections (SSTIs) regardless of the obesity classification, according to a review of 2868 patients with SSTIs, which found that obese patients were less likely to die in hospital than nonobese patients (odds ratio = 0.42, 95% confidence index, 0.25 to 0.7, P=0.001). [56]

Surprisingly, diabetes and HIV infection are not associated with higher mortality. In some studies, Fournier gangrene that originates from anorectal diseases carries a worse prognosis than cases caused by other factors.

The reported mortality rates for Fournier gangrene have varied widely, ranging as high as 75%. Joseph Jones, a Confederate army surgeon, was the first person to describe the mortality of Fournier gangrene in a large population of men. He reported a mortality rate of 46% in 2642 affected Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. [57]

Using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data from 2005 to 2009, Kim et al determined that the overall 30-day mortality rate for Fournier gangrene and necrotizing fasciitis of the genitalia was 10.1% (64 of 636 patients)—a rate about half that of historically published estimates, but similar to that in recent studies. [58] A review of 25.8 million hospital admission in 2001 and 2004, using the US State Inpatient Database, estimated that Fournier gangrene constituted only 0.02% of hospital admissions and carred a 7.5% case fatality rate. [40] A review by Furr et al of National Inpatient Sample data on Fournier gangrene from 2004 to 2012 found that inpatient mortality was 4.7%. [6]

Factors associated with high mortality include an anorectal source, advanced age, extensive disease (involving abdominal wall or thighs), shock or sepsis at presentation, renal failure, and hepatic dysfunction. [59] In a Turkish study of 50 patients, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae were significantly more common in patients who required mechanical ventilation, but A baumannii was the only microorganism associated with an increased mortality rate. [60]

Death usually results from systemic illness, such as sepsis (usually gram negative), coagulopathy, acute kidney injury, diabetic ketoacidosis, or multiple organ failure. Fatal tetanus associated with Fournier gangrene has been reported in the literature.

-

Necrotizing infection results when the pathogen is extremely virulent or, most commonly, when a combination of microorganisms act synergistically in a susceptible immunocompromised host.

-

Photomicrograph of Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis), oil immersion at 1000X magnification. Note the acute inflammatory cells in the necrotic tissue. Bacteria are located in the haziness of their cytoplasm. Courtesy of Billie Fife, MD, and Thomas A. Santora, MD.

-

Photograph of a morbidly obese male with long-standing phimosis. This condition led to urinary incontinence, perineal diaper rash–like dermatitis, and urinary tract infection. Ultimately, he presented with exquisite perineal pain. An examination with the patient under anesthesia was necessary to discover the necrotizing infection that appeared to originate in the right bulbourethral gland. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD.

-

Patient with Fournier gangrene following radical debridement. A dorsal slit was made in the prepuce to expose the glans penis. Urethral catheterization was performed. Incision into the point of maximal tenderness on the right side of the perineum revealed gangrenous necrosis that involved the anterior and posterior aspects of the perineum, the entirety of the right hemiscrotum, and the posterior medial aspect of the right thigh. The skin and involved fascia were excised from these areas. Reconstruction of this defect was performed in a staged approach. A gracilis rotational muscle flap taken from the right thigh was used to fill the cavity in the posterior right perineum as the first step. The remainder of the defect was covered with split-thickness skin grafts. This patient made a full recovery.

-

Fascial envelopment of the perineum (male). Note how Colles fascia completely envelops the scrotum and penis. Colles fascia is in continuity cephalad to the level of the clavicles. In the inguinal region, this fascial layer is known as Scarpa fascia. Familiarity with this fascial anatomy, along with recognition that necrotizing fasciitis tends to spread along fascial planes, makes it easy to understand how a process that starts in the perineum can spread to the abdominal wall, the flank, and even the chest wall.

-

Examination of an anesthetized man with alcoholism and known cirrhosis who presented with exquisite pain limited to the scrotum. Note the erythema of the scrotum and the look of skepticism on the face of one of the surgeons. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD.

-

In a man with alcoholism and known cirrhosis who presented with exquisite pain limited to the scrotum, opening of the scrotum along the median raphe liberated foul-smelling brown purulence and exposed necrotic tissue throughout the mid scrotum. The testicles were not involved. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD.

-

The same patient depicted in Images 6 and 7. Following resolution of the infection, the wound was covered with a split-thickness skin graft. The option of delayed primary closure of this wound was not chosen in this patient because of concern for tension on the closure. Courtesy of Thomas A. Santora, MD.