Practice Essentials

Penetrating abdominal trauma typically involves the violation of the abdominal cavity by a gunshot wound (see the image below) or stab wound.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of penetrating abdominal trauma depend on various factors, including the type of penetrating weapon or object, the range from which the injury occurred, which organs may be injured, and the location and number of wounds.

Close-range injuries transfer more kinetic energy than those sustained at a distance, although range is often difficult to ascertain when assessing gunshot wounds. A gunshot wound is caused by a missile propelled by combustion of powder. These wounds involve high-energy transfer and, consequently, can involve an unpredictable pattern of injuries. Secondary missiles, such as bullet and bone fragments, can inflict additional damage. Stab wounds are caused by penetration of the abdominal wall by a sharp object. This type of wound generally has a more predictable pattern of organ injury. However, occult injuries can be overlooked, resulting in devastating complications.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Initial examination (primary survey, or ABCDEs) in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma includes assessment of the following:

-

Airway, breathing, circulation (ABCs): Includes vital signs

-

Level of consciousness (D, disability): To detect neurologic deficits

-

Location(s) of the wound(s) (E, exposure): Inspect all body surfaces, and document all penetrating wounds

-

Type of penetrating weapon or object

-

Amount of blood loss

The secondary survey is a complete head-to-toe physical examination in hemodynamically stable patients and includes external inspection with respect to anatomic landmarks; abdominal evaluation for tympany, dullness to percussion, bowel sounds, and/or distention; and a digital rectal and genitourinary evaluation. In patients with life-threatening injuries, the secondary survey may be delayed for operative therapy.

Immediate surgical exploration is warranted for evidence of significant intra-abdominal injury, especially vascular trauma, such as the following:

-

Hypotension (with or without abdominal distention)

-

Narrow pulse pressure

-

Tachycardia

-

High or low respiratory rate

-

Signs of inadequate end organ perfusion

-

Peritoneal signs (eg, pain, guarding, rebound tenderness) and/or peritonitis

-

Diffuse and poorly localized pain that fails to resolve

Laboratory testing

In case emergent operation is necessary, all patients with penetrating abdominal trauma should undergo certain basic laboratory testing, as follows:

-

Blood type and cross-match

-

Complete blood count (CBC)

-

Electrolyte levels

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine level

-

Glucose level

-

Prothrombin time (PT)/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

-

Venous or arterial lactate level

-

Calcium, magnesium, and phosphate levels

-

Arterial blood gas (ABG)

-

Urinalysis

-

Serum and urine toxicology screen

Imaging studies

The following imaging studies may be used to evaluate patients with penetrating abdominal trauma:

-

Chest radiography: To rule out penetration of the chest cavity

-

Abdominal radiography in 2 views (anterior-posterior, lateral)

-

Chest and abdominal ultrasonography: Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST); includes 4 views (pericardial, right and left upper quadrants, pelvis)

-

Abdominal CT scanning (including triple-contrast helical CT): Most sensitive and specific study in identifying and assessing liver or spleen injury severity [1]

Other radiologic studies that may be useful include the following:

-

Skeletal survey: To detect any associated fractures

-

Brain CT scanning: To detect any coincident head injuries

-

Retrograde urethrogram/cystogram: To detect any urethral or bladder injury

-

Intraoperative intravenous pyelography: To assess contralateral renal function in patients with kidney damage necessitating nephrectomy

Procedures

The following may be diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma:

-

Gastric decompression in intubated patients: To prevent aspiration

-

Foley catherization: To monitor fluid resuscitation

-

Peritoneal lavage (open or closed): To identify hollow viscus or diaphragmatic injury

-

Tube thoracostomy: To relieve hemothorax/pneumothorax

-

Local wound exploration: Diagnostic aid to determine the track of penetration through the tissue layers

-

Laparoscopy: To evaluate and treat intra-abdominal injuries, including stab wounds to the anterior abdomen or those with uncertain peritoneal penetration

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The approach to patients with penetrating abdominal trauma depends on the following factors:

-

Mechanism and location of injury

-

Hemodynamic and neurologic status of the patient

-

Associated injuries

-

Institutional resources

Most trauma centers use an algorithm with multiple diagnostic modalities whose uses are based on the pattern of injuries and the clinical status of the patient.

Gunshot wounds are associated with a high incidence of intra-abdominal injuries and nearly always mandate laparotomy. Stab wounds are associated with a significantly lower incidence of intra-abdominal injuries; therefore, expectant management is indicated in hemodynamically stable patients.

Pharmacotherapy

The following medications may be used in the management of patients with penetrating abdominal trauma:

-

Analgesics (eg, morphine sulfate, fentanyl citrate)

-

Anxiolytics (eg, lorazepam, midazolam hydrochloride)

-

Antibiotics (eg, cefotetan, metronidazole hydrochloride, gentamicin sulfate, vancomycin hydrochloride, ampicillin sodium-sulbactam sodium)

-

Neuromuscular blocking agents (eg, succinylcholine, vecuronium bromide)

-

Immune enhancement (eg, tetanus toxoid adsorbed or fluid)

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Penetrating abdominal trauma typically involves the violation of the abdominal cavity by a gunshot wound (GSW) or stab wound. The management of penetrating abdominal trauma has evolved greatly over the last century.

Before World War I, penetrating trauma was managed expectantly and was nearly uniformly fatal. Laparotomy became the treatment of choice during World War I, but mortality remained high. By World War II, early laparotomy resulted in a survival rate close to 50%.

The 1950s afforded availability of antimicrobials, better understanding of fluid replacement, and faster transport from the scene, which further increased survival rates. By the late 1950s, mandatory laparotomy was the rule for the management of patients with abdominal penetrating trauma.

In 1960, Shaftan suggested selective management of patients with abdominal stab wounds after observing an increased rate of laparotomies without identifiable injuries. More recently, expectant management has also been used in the treatment of specific GSWs to the abdomen.

The introduction and refinement of diagnostic procedures and imaging studies, including peritoneal lavage, laparoscopy, computed tomography (CT), and focused ultrasonography, have directed the evolution of penetrating abdominal trauma management.

There has been a substantial evolution in patient management. Resuscitation protocols reflect the impact of appropriate crystalloid administration, the immunomodulatory properties of blood transfusions, and an understanding for physiologic end points of resuscitation.

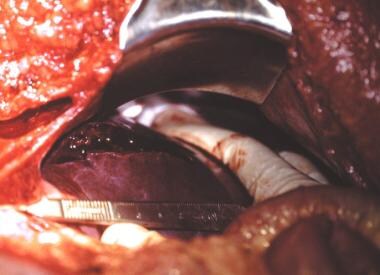

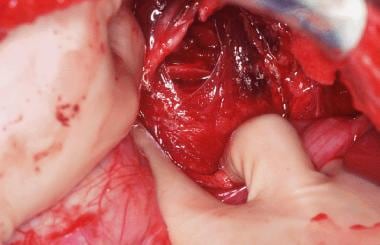

Damage control surgery (abbreviated laparotomy with physiologic resuscitation in the intensive care unit and staged abdominal reconstruction; see the images below) and treatment of abdominal compartment syndrome have had major impacts on care of the severely injured.

More recently, the damage control concept has been extended to resuscitation of severely injured patients with significant hemorrhage. Termed damage control resuscitation or hemostatic resuscitation, this approach arose from the recognition of early coagulopathy of trauma and its importance. Damage control resuscitation principles include early implementation of massive transfusion protocols with fixed blood product ratios, avoidance of large-volume crystalloid administration, and appropriate use of permissive hypotension.

Technologies allow less invasive and more rapid and specific diagnostic evaluations. Selective operative management and increasing application of angioembolization have served to further reduce surgical intervention. Refinement of evidence-based clinical pathways has allowed for a judicious allocation of resources.

See the gunshot wound images below.

This is an operative photograph of an extremely rare injury: a midureteral transection from a gunshot wound. The patient was shot with a MAC-10 machine gun and sustained liver injury as well as injuries to the duodenum, colon, terminal ileum, sigmoid colon, rectum, gallbladder, bladder, and left femur. He underwent a damage control operation and survived his injuries after 3 subsequent operations.

This is an operative photograph of an extremely rare injury: a midureteral transection from a gunshot wound. The patient was shot with a MAC-10 machine gun and sustained liver injury as well as injuries to the duodenum, colon, terminal ileum, sigmoid colon, rectum, gallbladder, bladder, and left femur. He underwent a damage control operation and survived his injuries after 3 subsequent operations.

This liver injury was sustained by the patient shot with a MAC-10 machine gun. The injury has been opened to control bleeding branches of the portal and hepatic veins as well as the hepatic arterial radicles. Several biliary ducts were ligated, and the back wall of the gallbladder can be identified in the depths of the wound. A cholecystectomy was required for management of the wound.

This liver injury was sustained by the patient shot with a MAC-10 machine gun. The injury has been opened to control bleeding branches of the portal and hepatic veins as well as the hepatic arterial radicles. Several biliary ducts were ligated, and the back wall of the gallbladder can be identified in the depths of the wound. A cholecystectomy was required for management of the wound.

Nevertheless, penetrating abdominal organ injury patterns and survival have plateaued over the past decade. Death from refractory hemorrhagic shock or exsanguination in the first 24 hours remains the most common cause of mortality. Damage control surgery is being used more frequently with improved early survival but with a concurrent increase in late morbidity. More study is needed to determine if wider application of massive transfusion protocols and damage control resuscitation principles will improve outcome further.

Anatomy

In evaluating patients with penetrating abdominal trauma, the abdomen is classically divided as follows:

-

Anterior abdomen - Anterior costal margins to inguinal creases, between the anterior axillary lines

-

Intrathoracic abdomen or thoracoabdominal area - Fourth intercostal space anteriorly (nipple) and seventh intercostal space posteriorly (scapular tip) to inferior costal margins

-

Flank - Scapular tip to iliac crest, between anterior and posterior axillary lines

-

Back - Scapular tip to iliac crest, between posterior and axillary line

This anatomic classification is important in guiding the clinician’s suspicion for specific organ injury.

Intraperitoneal abdominal organs include the solid organs (ie, spleen, liver) and the hollow viscus organs (ie, stomach, ileum, jejunum, transverse colon).

Retroperitoneal organs include the duodenum, pancreas, kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, ascending and descending colon, major abdominal vessels, and rectum.

Pathophysiology

A GSW is caused by a missile propelled by combustion of powder. These wounds involve high-energy transfer and, consequently, can involve an unpredictable pattern of injuries. Secondary missiles, such as bullet and bone fragments, can inflict additional damage. Military and hunting firearms have higher missile velocity than handguns, resulting in even higher energy transfer.

In penetrating abdominal trauma due to gunshot wounds, the most commonly injured organs are as follows [2] :

-

Small bowel (50%)

-

Colon (40%)

-

Liver (30%)

-

Abdominal vascular structures (25%)

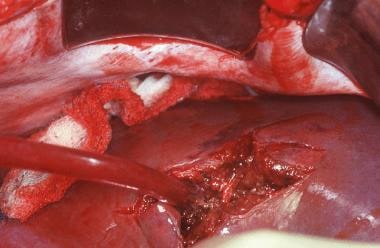

The image below is of a patient who sustained a gunshot wound to the spleen.

This 22-year-old woman sustained a gunshot wound to the left flank. At exploration, she had a through-and-through laceration of her spleen. The bleeding was arrested by finger compression of the splenic hilum while it was mobilized. A splenectomy was performed because the bullet went through the hilum.

This 22-year-old woman sustained a gunshot wound to the left flank. At exploration, she had a through-and-through laceration of her spleen. The bleeding was arrested by finger compression of the splenic hilum while it was mobilized. A splenectomy was performed because the bullet went through the hilum.

The severity of shotgun wounds depends on the distance of the victim from the weapon. The mass of a shot pellet is minimal, and thus its velocity decreases rapidly after the shell leaves the barrel of the gun. When the distance is less than 3 yd, the injury is considered high velocity; if the distance exceeds 7 yd, most of the buckshot penetrates only the subcutaneous tissue.

Stab wounds are caused by penetration of the abdominal wall by a sharp object. This type of wound generally has a more predictable pattern of organ injury. However, occult injuries can be overlooked, resulting in devastating complications.

In penetrating abdominal trauma due to stab wounds, the most commonly injured organs are as follows [2] :

-

Liver (40%)

-

Small bowel (30%)

-

Diaphragm (20%)

-

Colon (15%)

A stab wound is shown in the image below.

The patient's small intestine clearly protrudes through his anterior abdominal wall following a stab wound caused by a machete. The operative repair and recovery were uneventful.

The patient's small intestine clearly protrudes through his anterior abdominal wall following a stab wound caused by a machete. The operative repair and recovery were uneventful.

The mechanism that underlies the penetrating trauma (eg, gunshot wound, stab wound, impalement) relates to the mode of injury (eg, accidental or intentional injury, homicide, suicide). Homicide or intentional injury is the predominant mode of abdominal injury in this patient population. Accidental injury is most common in pediatric home firearm injuries but is uncommon by comparison to the overall levels of homicide and intentional injury. Suicide via penetrating abdominal trauma is uncommon.

The images below depict 2 patients with impalement injuries.

Note that the resident is carefully maintaining the position of the impaled stop sign post, so as not to dislodge the shaft. The shaft was removed in the OR along with the patient's right colon.

Note that the resident is carefully maintaining the position of the impaled stop sign post, so as not to dislodge the shaft. The shaft was removed in the OR along with the patient's right colon.

A 34-year-old man flipped over the handlebars of his motorcycle and landed on a wrought-iron fence. His helmet was knocked off when he landed. The medics cut the fence apart and transported the patient and fence to the ED (see image). On presentation, the patient's vital signs are as follows: rectal temperature, 95.3°F; heart rate, 126 beats per minute; respiration rate, 24 (labored); and blood pressure, 94/62 in his left arm. Intubation, bilateral upper extremity intravenous access, 2000 mL intravenous fluid, AP CXR, and operation is the correct sequence in which to resuscitate the patient to address the ABCs.

A 34-year-old man flipped over the handlebars of his motorcycle and landed on a wrought-iron fence. His helmet was knocked off when he landed. The medics cut the fence apart and transported the patient and fence to the ED (see image). On presentation, the patient's vital signs are as follows: rectal temperature, 95.3°F; heart rate, 126 beats per minute; respiration rate, 24 (labored); and blood pressure, 94/62 in his left arm. Intubation, bilateral upper extremity intravenous access, 2000 mL intravenous fluid, AP CXR, and operation is the correct sequence in which to resuscitate the patient to address the ABCs.

Etiology

Gunshot wounds, considered high-velocity projectiles, are the most common cause (64%) of penetrating abdominal trauma, followed by stab wounds (31%) and shotgun wounds (5%).

Penetrating abdominal trauma may result from urban violence. Domestic violence crosses all socioeconomic barriers and is an important consideration in the evaluation of injuries sustained at home and those reportedly involving the patient's family or significant other.

From a global perspective, penetrating abdominal trauma in most settings results principally from military actions and wars.

Penetrating abdominal trauma may be iatrogenically introduced. Documented complications of diagnostic peritoneal lavage include injuries to the underlying bowel, bladder, or major vessels such as the aorta or vena cava. Fortunately, the incidence of such complications is relatively small.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the United States, suicide and homicide consistently rank in the top 15 causes of death. According to data published by the National Vital Statistics Reports, 11,406 homicide deaths occurred from firearm injuries in 2009 and 18,689 deaths from self-inflicted GSWs. [3] Forty percent of homicides and 14% of suicides by firearm involved injuries to the torso.

Tracking trauma is the purview of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCICP). Data collected by this organization suggest that traumatic injury is the third overall leading cause of death and the number one cause of death in persons aged 1-44 years. Penetrating abdominal trauma affects approximately 35% of those patients admitted to urban trauma centers and 1-12% of those admitted to suburban or rural centers. [4]

International statistics

According to age-adjusted rates from 1990 to 1995, firearm mortality rates across the world vary widely, from 0.05 in Japan to 14.24 in the United States. Firearm-associated homicide mortality was highest in Mexico at 10.35; firearm associated suicide was highest in the United States at 6.3. The frequency of penetrating abdominal injury across the globe relates to the industrialization of developing nations, weapons available, and, significantly, to the presence of military conflicts. Therefore, frequency varies.

Racial differences in incidence

Age-adjusted firearm death rates are 2-7 times higher for non-Hispanic Black males than for males of other ethnicities. For non-Hispanic Whites, most firearms deaths are due to suicide.

Race distribution in patients with penetrating abdominal trauma depends significantly on the location of the receiving hospital. Urban centers predominantly receive young African-American and Hispanic males more frequently than young White males due to population demographics in these areas. A similar distribution occurs for their female counterparts.

Although quantifying the death rate for penetrating abdominal trauma by race is difficult, the relative risk of death for penetrating injury in general is known. African-American males have a 3-fold increase in relative risk of death compared with their White male counterparts. African-American females have a 2.5-fold increase in relative risk of death compared with their White female counterparts.

Suburban centers tend to receive a greater proportion of youthful to middle-aged White males as their predominant patient population because of regional demographics. [5]

Sex- and age-related differences in incidence

Males constitute the great majority of patients with penetrating trauma injuries across the United States and the world. In some areas of the United States, approximately 90% of patients with penetrating trauma are male. Injuries are the leading cause of death in patients aged 1-44 years. [6]

Prognosis

The death rate from penetrating abdominal trauma spans the entire spectrum (0-100%), depending on the extent of injury. Patients with violation of anterior abdominal wall fascia without peritoneal injury have a 0% mortality rate and minimal morbidity rate, while those with multiorgan injury complexes presenting with hypotension, base deficit less than -15 mEq/L HCO3, core temperature less than 35° C, and development of coagulopathy have a dramatically increased mortality rate mandating "damage control" resuscitation. [7]

An average mortality rate for all patients with penetrating abdominal trauma is approximately 5% in most level 1 trauma centers, but this population is necessarily biased, given the higher acuity seen at such centers, thus skewing the data.

Survival from penetrating abdominal trauma has not measurably changed in the past decade, largely because of death within 24 hours resulting from irreversible hemorrhagic shock and exsanguination. More than 80% of deaths occur within 24 hours of admission, 66.7% at the initial operation associated with abdominal vascular injury. In contrast, survival from penetrating abdominal injury without vascular injury remains high. [8]

Temporal distribution of deaths in penetrating trauma is significantly different from that in blunt trauma. The majority of deaths from penetrating trauma occur between 1 and 6 hours from admission. In contrast, the highest number of deaths from blunt trauma occurs beyond 72 hours postadmission and the lowest number occurs during the first hour. [8]

Consequently, deaths caused by penetrating trauma are significantly more likely to occur in the emergency department or the operating room than deaths caused by blunt trauma, which predominantly occur in the ICU. Hypoperfusion and its sequelae are the usual cause of death within the first 72 hours, whereas ICU deaths 2 or more weeks later are usually from complications related to sepsis, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. [8]

General factors that predict increased mortality from penetrating abdominal trauma include the following:

-

Female sex

-

Long interval between injury and operation

-

Presence of shock on admission

-

Coexisting cranial injury

The death rate is markedly influenced by prehospital hypotension, massive hemorrhage, arrest in the field or on presentation, acidosis with an initial pH less than 7, lactate level greater than 20 mmol/L, or base deficit more negative than -15 mEq HCO3. [8]

In a series by Nicholas and colleagues of 250 patients with penetrating abdominal trauma and positive laparotomies, the overall survival was 86.8%. [9] Mortality was found to be associated with the number of organs injured, vascular injury, and the need for damage-control surgery, emergency department thoracotomy, or operating room thoracotomy.

While damage-control surgery has been used with some success in the management of patients with extensive abdominal trauma, it is associated with significant morbidity, including sepsis, intra-abdominal abscess, and gastrointestinal fistula, according to Nicholas et al. [9]

Patients who present to the ED in the early postoperative period with abdominal pain or signs of infection should be strongly considered for CT scan and surgical consultation.

Injury patterns differ depending on the weapon. Low-velocity stab wounds are generally less destructive and have a lower degree of morbidity and mortality than gunshot wounds and shotgun blasts. Gunshot wounds and other projectiles have a higher degree of energy and produce fragmentation and cavitation, resulting in greater morbidity. [9]

Patient Education

Paramount importance must be placed on patient, family, and support system education if the medical community wishes to proactively reduce the incidence of violent injury in our society. Such an educational initiative should begin with the initial evaluation in the ED.

No single solution exists for every hospital or community; individualization is the key. Healthcare providers should be an integral part of reducing violence in society.

For patient education information, see the Wounds Center, as well as Puncture Wound.

-

Management of penetrating abdominal trauma. CT = computed tomography; DPL = diagnostic peritoneal lavage; RBC = red blood cells.

-

Penetrating abdominal trauma. Tangential gunshot wound to the liver.

-

Penetrating abdominal trauma. Strangulated small bowel in a patient with a previous gunshot wound to the abdomen.

-

Note that the resident is carefully maintaining the position of the impaled stop sign post, so as not to dislodge the shaft. The shaft was removed in the OR along with the patient's right colon.

-

This is an operative photograph of an extremely rare injury: a midureteral transection from a gunshot wound. The patient was shot with a MAC-10 machine gun and sustained liver injury as well as injuries to the duodenum, colon, terminal ileum, sigmoid colon, rectum, gallbladder, bladder, and left femur. He underwent a damage control operation and survived his injuries after 3 subsequent operations.

-

This liver injury was sustained by the patient shot with a MAC-10 machine gun. The injury has been opened to control bleeding branches of the portal and hepatic veins as well as the hepatic arterial radicles. Several biliary ducts were ligated, and the back wall of the gallbladder can be identified in the depths of the wound. A cholecystectomy was required for management of the wound.

-

The patient's small intestine clearly protrudes through his anterior abdominal wall following a stab wound caused by a machete. The operative repair and recovery were uneventful.

-

A standard diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) catheter is secured in place following an open DPL. An aspirating syringe is attached to the catheter via extension tubing as the initial step in the evaluation for intraperitoneal blood.

-

An ED thoracotomy has been performed, and the aorta is cross-clamped. Note the proper positioning of the ratchet mechanism of the rib spreader to allow extension of the incision to the right chest for a clamshell thoracotomy if needed. This patient arrived with a weak pulse and a systolic blood pressure of 40 mm Hg and promptly died on the ED stretcher. An ED thoracotomy was performed for cardiopulmonary-cerebral resuscitation.

-

This 22-year-old woman sustained a gunshot wound to the left flank. At exploration, she had a through-and-through laceration of her spleen. The bleeding was arrested by finger compression of the splenic hilum while it was mobilized. A splenectomy was performed because the bullet went through the hilum.

-

A 34-year-old man flipped over the handlebars of his motorcycle and landed on a wrought-iron fence. His helmet was knocked off when he landed. The medics cut the fence apart and transported the patient and fence to the ED (see image). On presentation, the patient's vital signs are as follows: rectal temperature, 95.3°F; heart rate, 126 beats per minute; respiration rate, 24 (labored); and blood pressure, 94/62 in his left arm. Intubation, bilateral upper extremity intravenous access, 2000 mL intravenous fluid, AP CXR, and operation is the correct sequence in which to resuscitate the patient to address the ABCs.