Practice Essentials

Mediastinitis is a life-threatening condition that carries an extremely high mortality if recognized late or treated improperly. [1, 2, 3, 4] Although long recognized as a complication of certain infectious diseases, most cases of mediastinitis are associated with cardiac surgery (>300,000 cases per year in the United States). [4, 5] This complication affects approximately 1-2% of these patients. Although small in proportional terms, the actual number of patients affected by mediastinitis is substantial. This significantly increases mortality and cost.

After years of evolution, optimal therapy for mediastinitis is more clearly understood. Future directions for research should focus on prevention, including timely antibiotic administration, sterile technique, prophylactic measures such as topical bacitracin, and meticulous hemostasis. The focus should also include more accurate methods of diagnosis during the first 14 days after surgery, when computed tomography (CT) findings are not reliable.

However, the keys to successful management remain early recognition and aggressive treatment, including sternal reopening and debridement. Further research should also focus on the optimal timing and method of wound closure and the duration of antibiotic therapy required for optimal treatment.

Anatomy

The portion of the thorax defined as the mediastinum extends from the posterior aspect of the sternum to the anterior surface of the vertebral bodies and includes the paravertebral sulci when the locations of specific mediastinal masses are defined. It is limited bilaterally by the mediastinal parietal pleura and extends from the diaphragm inferiorly to the level of the thoracic inlet superiorly.

Traditionally, the mediastinum is artificially subdivided into three compartments (anterior, middle, and posterior) for better descriptive localization of specific lesions. When the location or origin of specific masses or neoplasms is discussed, the compartments or spaces are most commonly defined as follows:

-

Anterior - The anterior compartment extends from the posterior surface of the sternum to the anterior surface of the pericardium and great vessels, and it normally contains the thymus gland, adipose tissue, and lymph nodes; the physiology of the anterior mediastinum includes the lymphatics and thymus gland

-

Middle - The physiology of the middle mediastinum includes the bronchi, the heart and pericardium, the hila of both lungs, the lymph nodes, the phrenic nerves, the great vessels, and the trachea

-

Posterior - The physiology of the posterior mediastinum includes the azygos vein, the descending aorta, the esophagus, the lymph nodes, the thoracic duct, and the vagus and sympathetic nerves

Pathophysiology

Infection from either bacterial pathogens or more atypical organisms can inflame any of the mediastinal structures, causing physiologic compromise by compression, bleeding, systemic sepsis, or a combination of these.

The origin of infection following open heart operations is not known in most patients. Some believe that the process begins as an isolated area of sternal osteomyelitis that eventually leads to sternal separation. Others hold that sternal instability is the inciting event, and bacteria then migrate into deeper tissues. Inadequate mediastinal drainage in the operating room may also contribute to the development of a deeper chest infection.

The patient's own skin flora and the bacteria in the local surgical environment are possible sources of infection as well. Because some bacterial contamination of surgical wounds is inevitable, host risk factors are likely critical in promoting an active infection.

Etiology

Most cases of mediastinitis in the United States occur following cardiovascular surgery. Risk factors for the development of mediastinitis in this setting include the following:

-

In general, the use of pedicled bilateral internal thoracic (mammary) artery (BITA) grafts carries increased risk for mediastinitis after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), [6] and this risk is even higher among patients with diabetes, thus rendering many surgeons reluctant to use BITA grafting in this subgroup of patients; however, the use of skeletonized BITA grafts may reduce the risk, and this approach could be considered for patients with and without diabetes [7] ; there is growing evidence to suggest that diabetes is not necessarily a contraindication for BITA grafting [8]

-

Emergency surgery [9]

-

External cardiac compression (conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation)

-

Obesity (>20% of ideal body weight) [10]

-

Postoperative shock, especially when multiple blood transfusions are required [11]

-

Reexploration following initial surgery

-

Surgical technical factors (eg, excessive use of electrocautery, bone wax, paramedian sternotomy) [9]

A study by Perrault et al found that higher body mass index, higher creatinine level, the presence of peripheral vascular disease, preoperative corticosteroid use, and ventricular assist device or transplant surgery were all associated with an increased risk of mediastinal infection; in nondiabetic patients, postoperative hyperglycemia was associated with an increased infection risk. [13]

Additional causes include the following:

-

Trauma, especially blunt trauma to the chest or abdomen

-

Tracheobronchial perforation, due to either penetrating or blunt trauma or instrumentation during bronchoscopy

-

Progressive odontogenic infection ( Ludwig angina)

-

Mediastinal extension of lung infection

-

Chronic fibrosing mediastinitis due to granulomatous infections [18]

Microbiology

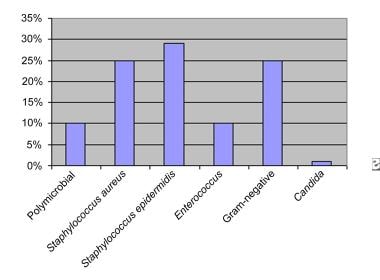

Most mediastinitis cases involve gram-positive cocci, [9] with Staphylococcus aureus [21] and Staphylococcus epidermidis accounting for 70-80% of cases (see the image below). [12] Mixed gram-positive and gram-negative infections account for approximately 40% of cases. Isolated gram-negative infections are rare causes. Postoperative mediastinitis caused by Serratia marcescens has been reported. [22]

The frequency of various microbiological pathogens isolated in cases of postoperative mediastinitis.

The frequency of various microbiological pathogens isolated in cases of postoperative mediastinitis.

Fibrosing mediastinitis is most commonly associated with Histoplasma capsulatum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, though mediastinitis is an extremely rare complication of these infections. [18]

Acute mediastinitis has also been reported as a complication of Epstein-Barr virus infection. [23]

Epidemiology

In the United States, mediastinitis most commonly occurs in the postoperative setting following CABG. [4] The reported incidence of mediastinitis after cardiac surgery has ranged from 0.3% to 3.4%. [5] At most large surgical centers, the incidence is in the range of 1-2%; however, certain subsets of patients, such as patients who have undergone a heart transplant, are at much higher risk.

Prognosis

The development of mediastinitis dramatically increases mortality. One study showed that postoperatively, a patient's chance of dying was twice as high when mediastinitis developed as it was when mediastinitis was absent (12% vs 6%). In a review by Goh, in-hospital mortality for poststernotomy mediastinitis ranged from 1.1% to 19%. [5] Some studies have reported death rates as high as 47%. Mediastinitis also raises the 2-year mortality from 2% to 8% following CABG.

Mediastinitis substantially lengthens the hospital stay as well. Patients with postoperative mediastinitis stay in the hospital six to seven times longer than those without the condition, and total costs may triple. [24]

-

The frequency of various microbiological pathogens isolated in cases of postoperative mediastinitis.